Constellation facts for kids

|

|||

|

|||

A constellation is a group of bright stars that look like a pattern in the night sky. People imagine these patterns as animals, mythical heroes, or objects.

People have been looking at constellations for thousands of years. Ancient cultures used them to tell stories about their beliefs and history. This is why different cultures often had their own unique constellations. Over time, many constellations changed in size or shape. Some became popular and then disappeared, while others were only used by certain groups.

In the northern part of the world, many traditional constellations came from ancient Greece. These include the 48 patterns mentioned by Aratus and Ptolemy. However, these star patterns were likely known long before these writings. New constellations in the far southern sky were added much later. This happened between the 15th and 18th centuries. European explorers traveling south discovered these new star groups.

Twelve important constellations are part of the zodiac. This is the path the Sun, Moon, and planets follow across the sky. The idea of the zodiac probably started thousands of years ago. Its astrological divisions became important around 400 BCE in ancient Babylonia.

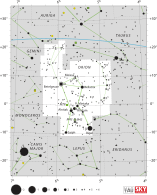

To help astronomers find objects in the sky, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) officially recognized 88 modern constellations in 1928. Now, every spot in the sky belongs to a specific constellation. Many star naming systems also use the constellation name to help people know where an object is. For example, the Flamsteed designation for bright stars includes a number and the constellation's name.

Sometimes, the word "constellation" can also mean the stars within or near these official boundaries. Groups of stars that are not official constellations are called asterisms. Examples include the Pleiades, the Hyades, or the False Cross.

Contents

What is a Constellation?

The word "constellation" comes from a Latin term meaning "set of stars." It started being used in English around the 14th century. In astronomy, a constellation is a recognizable pattern of stars. These patterns are often linked to mythical characters, creatures, or objects. It can also refer to the 88 officially recognized constellations we use today.

A circumpolar constellation is a constellation that never sets below the horizon from a certain place on Earth. If you are at the North Pole or South Pole, all constellations in the southern or northern sky are circumpolar.

Even though stars in a constellation look close together, they are usually very far apart from each other. Stars also move through space. This means the shapes of constellations slowly change over time. After thousands of years, their familiar outlines will look different. Astronomers can predict how constellations looked in the past or will look in the future. They do this by studying how stars move.

Early Constellations: A Look Back

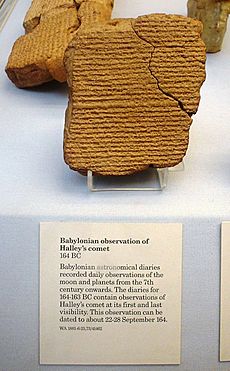

The oldest evidence of constellations comes from ancient stones and clay tablets. These were found in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and date back to 3000 BC. Most Mesopotamian constellations were created between 1300 and 1000 BC. Many of these groupings later appeared in the classical Greek constellations.

Constellations in Ancient Babylon

The Babylonians were the first to realize that astronomical events happen in cycles. They also used math to predict these events. The oldest Babylonian star catalogs date back to around 1000 BC. However, many Sumerian names in these catalogs suggest they were based on even older Sumerian traditions.

The classical Zodiac we know today came from a revised Babylonian system around the 6th century BC. The Hebrew Bible also shows knowledge of the Neo-Babylonian zodiac. For example, some scholars believe the creatures in the Book of Ezekiel represent parts of the Zodiac.

The Greeks adopted the Babylonian system in the 4th century BC. Twenty of Ptolemy's constellations came directly from the Ancient Near East. Another ten used the same stars but had different names.

Constellations in Ancient China

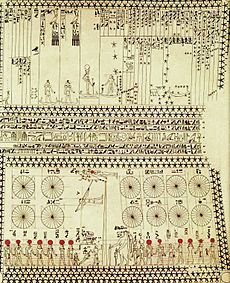

In ancient China, people had a long history of carefully observing the sky. Star names, later grouped into the twenty-eight mansions, have been found on oracle bones. These bones were found at Anyang and date back to the middle Shang Dynasty. These Chinese constellations are very old and important. They have been recorded since the 5th century BC. Some similarities to early Babylonian star catalogs suggest the ancient Chinese system might not have developed completely on its own.

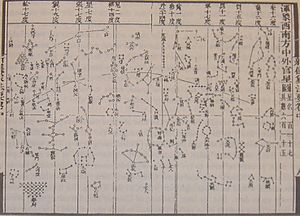

Classical Chinese astronomy was recorded during the Han period. It came from three different schools of thought from the Warring States period. An astronomer named Chen Zhuo combined these three systems in the 3rd century. Although Chen Zhuo's work is lost, we know about his system from Tang period records. The oldest Chinese star chart we still have is from this time. It was found as part of the Dunhuang Manuscripts.

Chinese astronomy continued to grow during the Song dynasty. During the Yuan Dynasty, it was influenced by medieval Islamic astronomy. Maps made during this time were more scientific and reliable.

A famous map from the Song Period is the Suzhou Astronomical Chart. It shows carvings of most stars in the Chinese sky on a stone plate. This map was very accurate and even shows the supernova of 1054 in the constellation Taurus.

Later, during the Ming Dynasty, Chinese star charts were influenced by European astronomy. More stars were added, especially in the southern sky, which ancient Chinese astronomers hadn't fully mapped. These new stars were added to existing constellations or formed new ones. Xu Guangqi and Johann Adam Schall von Bell, a German Jesuit, made further improvements. Their work was recorded in the Chongzhen Lishu (1628). With these changes, Chinese star maps included 23 new constellations with 125 stars from the southern hemisphere. This helped connect Chinese astronomy with the rest of the world.

Modern Constellations and Their History

Historically, constellations are divided into two main groups: those in the northern sky and those in the southern sky. The northern constellations have mostly survived since ancient times. Their names often come from Greek legends or have unknown origins. We know about these constellations from star charts. The oldest example is on a statue called the Farnese Atlas, which might be based on the star catalog of the Greek astronomer Hipparchus.

Southern hemisphere constellations are more recent. They were created as new groups or replaced older ones, like Argo Navis. Some southern constellations became outdated, or their long names were shortened. For example, Musca Australis became simply Musca.

After the invention of the optical telescope, astronomers needed better ways to map and locate objects in the sky. This was important for navigation and astronomy. So, they needed clearer definitions for constellations and their boundaries. Johann Bayer was the first to assign stars within each constellation in 1603. He used the letters of the Greek alphabet in his star atlas "Uranometria." Later star atlases helped develop the modern constellations we use today.

Where Did Southern Constellations Come From?

Much of the sky near the South Celestial Pole was not observed by ancient Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks, Chinese, or Persian astronomers. Knowledge of different stars in the southern skies goes back to ancient times. This knowledge came from reports by Phoenician sailors, like those from an expedition around Africa commissioned by Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II around 600 BC. However, most of this ancient knowledge was likely lost when the Library of Alexandria was destroyed.

Many of the 88 IAU-recognized constellations in this region were adopted in the late 16th century by Petrus Plancius. His work was based on observations by Dutch navigators Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman. They added fifteen constellations by the end of the 16th century. Petrus Plancius added ten more, including Apus, Chamaeleon, Columba, Dorado, Grus, Hydrus, Indus, Musca, Pavo, Phoenix, Triangulum Australe, Tucana, and Volans.

Most of these early constellations didn't officially appear until a century after they were created. They were shown by German Johann Bayer in his star atlas Uranometria in 1603. Nicolas Louis de Lacaille, a French astronomer, created seventeen more in 1763. These appeared in his star catalog published in 1756.

The 88 Modern Constellations

The current list of 88 constellations was recognized by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 1922. This list is based on the 48 constellations from Ptolemy's Almagest (2nd century). It also includes newer additions and changes made by astronomers like Petrus Plancius (1592-1613), Johannes Hevelius (1690), and Nicolas Louis de Lacaille (1763). De Lacaille studied the stars of the southern hemisphere from 1750 to 1754 from the Cape of Good Hope. He observed over 10,000 stars using a small refracting telescope.

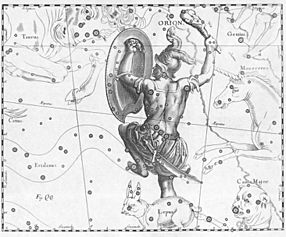

In 1922, Henry Norris Russell helped the IAU divide the sky into 88 official constellations. Before this, Ptolemy's list, with many additions, was used. However, these divisions didn't have clear borders. In 1930, Eugene Delporte, a Belgian astronomer, created an official map. This map clearly marked the areas of the sky for each constellation. Where possible, these modern constellations kept the names of their ancient Greek and Roman ancestors, like Orion, Leo, or Scorpius. The goal was to divide the entire sky into clear, connected areas. Out of the 88 modern constellations, 36 are mostly in the northern sky, and 52 are mostly in the southern sky.

In 1930, Eugène Delporte drew the boundaries between the 88 constellations. He used vertical and horizontal lines based on right ascension and declination. However, the data he used was from 1875. This was when Benjamin Apthorp Gould first suggested drawing boundaries for the sky. Because of the precession of the equinoxes (a slow wobble of Earth's axis), these borders on a modern star map (like one from 2000) are already a bit tilted. They are no longer perfectly vertical or horizontal. This tilt will continue to increase over many years.

Dark Cloud Constellations

The Great Rift is a series of dark patches in the Milky Way. It is much easier to see in the southern hemisphere than in the northern. It stands out clearly when the sky is very dark. Some cultures have seen shapes in these dark patches. They have given names to these "dark cloud constellations." The Inca people saw various dark areas or dark nebulae in the Milky Way as animals. They connected their appearance to the seasonal rains. Australian Aboriginal astronomy also describes dark cloud constellations. The most famous is the "emu in the sky." Its head is formed by the Coalsack, which is a dark cloud of dust, not stars.

Images for kids

-

The Emu in the sky – a constellation defined by dark clouds rather than by stars. The head of the emu is the Coalsack with the Southern Cross directly above. Scorpius is to the left.

-

Inca dark cloud constellations in the Mayu (Celestial River), also known as the Milky Way. The Southern Cross is above Yutu, while the eyes of the Llama are Alpha Centauri and Beta Centauri.

See also

In Spanish: Constelación para niños

In Spanish: Constelación para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |