Douglas Jardine facts for kids

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name |

Douglas Robert Jardine

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 23 October 1900 Malabar Hill, Bombay, Bombay Presidency, British India |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 18 June 1958 (aged 57) Montreux, Vaud, Switzerland |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | The Iron Duke | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Right-handed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Right-arm leg break | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Top-order Batsman | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut (cap 235) | 23 June 1928 v West Indies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 10 February 1934 v India | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1920–1923 | Oxford University | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1921–1933 | Surrey | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1925–1933/34 | Marylebone Cricket Club | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Source: CricInfo, 17 May 2008

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

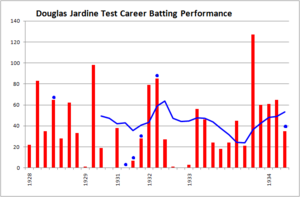

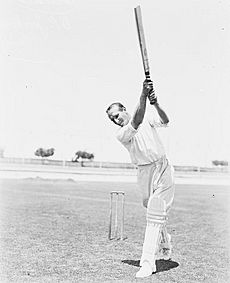

Douglas Robert Jardine (born 23 October 1900 – died 18 June 1958) was an English cricket player. He played 22 Test matches for England. He was captain in 15 of those matches between 1931 and 1934. Jardine was a right-handed batsman. He is most famous for leading the English team during the 1932–33 Ashes tour of Australia. In that series, England used "Bodyline" tactics against Australian batsmen like Donald Bradman. This meant bowlers aimed the ball short at the batsman's body, which many thought was dangerous. As captain, Jardine was in charge of using Bodyline.

Jardine was a strong personality in cricket. Some people saw him as arrogant. He was not popular in Australia, especially after the Bodyline tour. However, many players who played under him thought he was a great and dedicated captain. He was also known for wearing a multi-coloured Harlequin cap.

Douglas Jardine started as a talented schoolboy batsman. He played for Winchester College and then for Oxford University. Later, he played for Surrey County Cricket Club as an amateur player. He batted in a careful, defensive way, which was unusual for an amateur at the time. He was first chosen for Test matches in 1928. He played well in Australia in 1928–29. Later, his work meant he played less cricket. But in 1931, he was asked to captain England. He led England for the next three seasons and on two tours overseas. One of these was the famous Australian tour of 1932–33. As captain, he won nine of his 15 Tests, drew five, and lost only one. He stopped playing all first-class cricket in 1934 after a tour to India.

After cricket, Jardine worked in banking and later as a journalist. He joined the army during World War II and spent much of it in India. After the war, he worked for a paper company and returned to journalism. In 1957, he became ill and died in 1958 at age 57.

Contents

Early Life and School Cricket

Starting Cricket Young

Douglas Jardine was born on 23 October 1900 in Bombay, British India. His parents were Scottish. His father, Malcolm Jardine, was a former first-class cricketer and a lawyer. When Douglas was nine, he went to live with his aunt in St Andrews, Scotland.

From May 1910, he went to Horris Hill School. He did fairly well in his studies. From 1912, he played cricket for the school's main team. He was good at both bowling and batting. In his last year, he was captain and his team did not lose a single game. Jardine learned a lot about batting from the writings of former England captain C. B. Fry. His school coach did not like Jardine's batting style, but Jardine stuck to his own way, quoting Fry's book.

Excelling at Winchester College

In 1914, Jardine went to Winchester College. Life at Winchester was tough, with strict rules. Sports were a very important part of the school day. Students were taught to be honest and strong. Jardine was already known as a great cricketer. He also played football as a goalkeeper and rackets.

He was on the main cricket team for three years from 1917. He was coached by famous cricketers like Harry Altham and Schofield Haigh. In 1919, his last year, Jardine had the best batting average for the school. He scored 997 runs at an average of 66.46. He became captain, even though some people doubted his ability to unite the team. Under Jardine, Winchester beat Eton College in their yearly match in 1919. This was their first win against Eton in 12 years. Jardine's batting (35 and 89 runs) and leadership were key. Years later, he said his 89 runs in that match was his favourite innings. He also scored 135 not out against Harrow School.

Jardine's success was reported in newspapers. He played in two special matches for the best schoolboy cricketers at Lord's Cricket Ground. He scored well and received good reviews. Wisden, a famous cricket book, said in 1928 that Jardine was much better than other players his age. He was especially good at defence and hitting the ball on the on side. However, some people thought he was too careful and did not use all his batting skills.

Playing First-Class Cricket

Oxford University Days

Jardine started at New College, Oxford, in September 1919. He played several sports there. He played football for his college and tried out for the university team. He also played rackets and real tennis, becoming very good at real tennis. In cricket, Jardine was coached by Tom Hayward. Hayward helped him with his footwork and defence.

In the 1920 season, Jardine played his first official first-class cricket match. He played eight matches and scored two half-centuries. He mostly batted first in the order. He played in the important University Match against Cambridge. He scored 217 runs at an average of 22.64 that season. In a match against Essex, he took six wickets for 28 runs, bowling leg breaks. This was the only time he took five or more wickets in an innings.

In 1921, Jardine played more confidently. He scored three half-centuries in his first three matches. Oxford then played against the Australian touring team. In one innings, Jardine scored 96 not out. He saved the game but could not reach his century before the game ended. Many people praised his innings. Some critics wondered if this incident led to Jardine's later dislike of Australians. However, others said Jardine batted too slowly to get his century.

After Oxford, Jardine played for Surrey. He scored his first century for Surrey against Yorkshire. He was given his County Cap. He finished the season with 1,015 runs at an average of 39.03.

Joining Surrey County Cricket Club

Jardine missed most of the 1922 season because of a serious knee injury. He only played four matches. He was expected to do very well that year. Even so, he was chosen as one of the men of the year by The Isis magazine. After his knee problems, Jardine returned to cricket in May 1923. He was not made Oxford captain in his final year. This might have been because of his strong personality or his injury.

Jardine slowly found his batting form. He helped Oxford win their only match against Cambridge in that decade. In one match, he was criticised for using his pads to stop the ball from hitting the wickets. This was allowed by the rules but some thought it was against the spirit of the game. Jardine started to dislike the press and critics after this. He also got criticism for batting too slowly for Oxford. This was partly because the team often depended on him to score runs. Jardine left Oxford in 1923. He had scored 1,381 runs and earned a fourth class degree in modern history.

When Jardine played for Surrey that season, he batted more freely. He batted at number five and changed his style depending on the game. He was successful, playing long defensive innings or hitting quick runs. His captain, Percy Fender, kept him in that role.

Becoming a Top County Player

After Oxford, Jardine began training to be a lawyer while still playing for Surrey. He improved steadily over the next three seasons. He was made vice-captain to Fender for the 1924 season. He was chosen for the important Gentlemen v Players match for the first time. He scored 1,249 runs at an average of 40.29 that season.

In the next season, Jardine did not do as well. He scored fewer runs at a lower average. He missed the Gentlemen v Players match due to an ankle injury. In 1926, Jardine had his best season yet, with 1,473 runs (average 46.03). Towards the end of the season, his batting became more exciting. He started hitting more attacking shots. He scored 538 runs in his last ten innings.

In 1927, Jardine achieved his highest average in a season. He scored 1,002 runs and averaged 91.09 in a very wet summer. Wisden named him one of its Cricketers of the Year. They said he had improved his style. He only played 11 matches that season because of his work at Barings Bank. Despite less practice, he scored centuries in his first three matches. He also scored a century in the Gentlemen v Players match. This impressed important people at Lord's. He captained The Rest team against England in a trial match. He was praised for his performance. By this time, it was clear he would tour Australia that winter.

Becoming a Test Cricketer

First Matches for England

Jardine's batting in 1928 was excellent. He played 14 matches, scoring 1,133 runs at an average of 87.15. He did well in big matches. He scored 193 for Gentlemen at the Oval. The crowd booed his slow start but later cheered him. He captained The Rest against England in a Test trial. He made the highest score in both innings. He scored 74 not out in the fourth innings to help his team draw the game.

Right after this match, Jardine played his first Test match against the West Indies. This was West Indies' first ever Test match. Their fast bowlers were good, but Jardine played them confidently. Jardine played in the first two Tests, which England won easily. He scored 22 on his debut and 83 in the second Test. During his 83-run innings, he accidentally hit his wicket but was given not out. The rules at the time said a batsman was not out if his shot was complete and he was starting to run.

First Tour to Australia (1928-29)

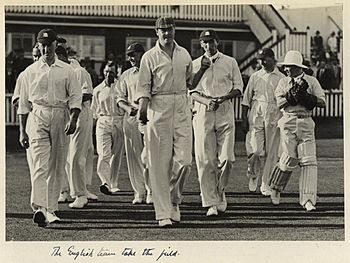

Jardine was chosen to tour Australia with the M.C.C. team in 1928–29. He was part of a very strong batting team. He played in all five Test matches and scored 341 runs at an average of 42.62. In all first-class matches, he scored 1,168 runs (average 64.88). Wisden said he was very successful. They praised his strong defensive shots.

Jardine started the tour with three centuries in a row. In his second century, the crowd booed him for batting too slowly. His third century was described as one of the best displays of batting. The crowds started to dislike him more and more. This was partly because of his success, but also because of his serious attitude and his choice of cap. He wore a Harlequin cap, given to good Oxford cricketers. Australian crowds did not understand this. They thought he was acting superior. One person in the crowd even shouted, "Where's the butler to carry the bat for you?" Jardine's cap became a target for jokes and criticism.

Jardine fielded near the crowd on the boundary. He was not a good fielder there and was often mocked. In one Test match, he spat towards the crowd. Jardine developed a strong dislike for Australian crowds. He once said that "All Australians are uneducated, and an unruly mob."

In the first Test, Jardine scored 35 and 65 not out. His first innings helped England from a difficult position. He played very carefully. England won by a huge margin. Jardine played a similar role in the second Test, helping England win by eight wickets. He scored 62 in the third Test. England needed 332 runs to win on a very bad pitch. Jack Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe batted well. Hobbs sent a message that Jardine should bat next. Jardine survived until the end of the day. He scored 33 the next day, and England won.

In the fourth Test, Jardine scored 98 runs. He batted with Wally Hammond in a partnership of 262 runs. This was the highest partnership for the third wicket in Test matches at the time. The scoring was very slow, and the crowd protested. England won the match by 12 runs.

Jardine was not successful in the final Test. He left the match early to catch a boat to India for a holiday. It is not clear why he left. Jardine later wrote about Australian crowds, complaining about their involvement. He also praised their knowledge of the game. Jardine did not play first-class cricket in 1929 due to work.

England Captaincy and Bodyline

Becoming England Captain

At the start of the 1930 season, Jardine was offered the vice-captaincy of Surrey. He could not accept due to work. He played only nine matches that season. He was not considered for Test selection. That season, Donald Bradman of Australia scored 974 runs against England. This made English selectors realise they needed a plan to stop him. Australia won the Ashes 2–1.

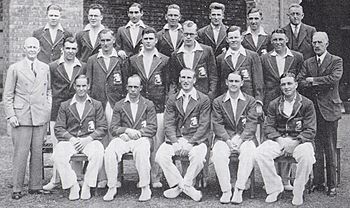

Jardine played a full season in 1931. In June, he was made captain for the Test against New Zealand. The English selectors were looking for a captain for the 1932–33 tour of Australia. They were worried about Bradman. Jardine was chosen as a reliable batsman and to see his leadership skills.

In his first Test as captain, Jardine had some disagreements with players. He was criticised for not telling his batsmen to score faster to win. The match was drawn. England won the series 1–0. Jardine did not score many runs in the series. Wisden said he did not impress everyone with his captaincy. But as a batsman, he was good. He scored 1,104 first-class runs that season.

At the start of the 1932 season, Jardine became captain of Surrey. He developed a more aggressive captaincy style. Surrey finished in a high position. England played India's first ever Test match that season. Jardine was captain. India had good bowlers. Jardine was the only English batsman to score over 30 in both innings. He scored 79 and 85 not out. He was praised for his defensive innings. During the match, Jardine again had disagreements with his team. He told bowlers Bill Bowes and Bill Voce to bowl a full toss each over. The bowlers did not do it and Jardine told them to obey orders. Jardine scored 1,464 runs that season.

Planning the Bodyline Tour

A week after the India Test, it was announced that Jardine would captain the M.C.C. team to Australia that winter. Some people worried if he was the best choice. But the selectors felt a strong leader was needed to beat the Australians. Jardine started planning tactics. He knew that Bradman sometimes struggled against fast bowling. During a match in 1930, Bradman seemed uncomfortable when the ball bounced high and fast. Percy Fender noticed this and discussed it with Jardine in 1932. When Jardine saw film of this, he shouted, "I've got it! He's yellow!"

Jardine met with Nottinghamshire captain Arthur Carr and his fast bowlers Harold Larwood and Bill Voce. Jardine explained that Bradman was weak against bowling aimed at his leg stump. If they could bowl accurately there, it would limit Bradman's scoring. He asked Larwood and Voce if they could bowl accurately at leg stump and make the ball rise towards the batsman's body. They agreed it might work. Jardine stressed that accuracy was very important. Larwood believed Jardine wanted to attack Bradman's mind as well as his batting.

Jardine also visited Frank Foster, who had toured Australia before. They discussed where to place fielders for Australian conditions. Foster had used similar tactics with fielders close on the leg-side. The team for Australia was announced. The choice of four fast bowlers was unusual. This was noticed by the Australian media. Jardine likely chose Eddie Paynter for the team. Jardine thought a player's record against northern counties was a good sign of international potential.

The Bodyline Tour

Beginning of the Tour

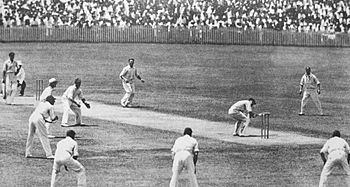

Wisden called this tour "probably the most controversial tour in history." England won four of the five Tests. But it was the way they played that caused so much argument. On the boat to Australia, Jardine stayed away from his team. He gave them rules, like not giving autographs. He also started having disagreements with Pelham Warner, one of the team managers. He talked tactics with Larwood and other bowlers. Some players said Jardine told them to hate the Australians to win. He had decided on leg theory, which led to Bodyline, as his main tactic.

When the team arrived, Jardine quickly upset the press. He refused to give team details or cooperate with journalists. The press wrote negative stories. Crowds booed him, making him angry. Jardine still wore his Harlequin cap. He started the tour well with scores of 98 and 127. He again had a disagreement with bowler Bill Bowes. Bowes did not want to bowl where Jardine asked. But after a talk, Bowes agreed to Jardine's tactics.

In a tour match, Jardine told Wally Hammond to attack the bowling of Chuck Fleetwood-Smith. He did not want Fleetwood-Smith to play in the Tests. So far, the English bowling was not very unusual. Larwood and Voce had been given light work. This changed in a match against an Australian XI. Jardine rested himself. The bowlers used the tactics that became known as Bodyline for the first time. Under captain Bob Wyatt, the bowlers bowled short and around leg stump. Fielders were placed close on the leg side to catch deflections. Wyatt later said this was not planned. These tactics continued in the next match. Several players were hit. Many people criticised this bowling style. It was seen as dangerous and against the spirit of the game. Jardine wrote that he had to move more and more fielders to the leg side. He said, "if this goes on I shall have to move the whole bloody lot to the leg side." Jardine disagreed more with Warner about Bodyline. But his tactics were working. Bradman had scored only 103 runs in six innings before the Tests.

Test Matches and Controversy

In the first Test, Jardine continued with Bodyline. Bradman did not play in this match. When Stan McCabe scored 187 not out, Jardine seemed worried. But England won the match easily. In the second Test, Jardine made a mistake with the pitch. He did not pick a specialist spinner, but the pitch later favoured one. The match started well when Bill Bowes bowled Bradman out on his first ball. Jardine was so happy he clapped his hands above his head and did a "war dance." This was very unusual for Jardine, who rarely showed emotion. In the second innings, Bradman scored a century. Australia won the match and tied the series. This made critics think Bodyline was not so dangerous.

Jardine had more disagreements with his team. He argued with Gubby Allen about his refusal to bowl Bodyline. The Nawab of Pataudi refused to field in the "leg trap." Jardine then allowed Pataudi to play little part in the tour.

The third Test was very controversial. Jardine promoted himself to open the batting. England collapsed to 30 for four. The trouble started when Bill Woodfull was hit on the chest by a Larwood ball. Jardine said, "Well bowled, Harold," aiming it at Bradman, who was also batting. For the next ball, the fielders moved into Bodyline positions. Jardine later regretted moving the fielders then. Later, Bert Oldfield suffered a fractured skull. Players feared a riot. Police were brought in. Jardine then batted very slowly, scoring 56. The crowd booed him constantly. England won, but Wisden called it "probably the most unpleasant match ever played." However, it praised Jardine's courage and leadership.

After the third Test, strong messages were sent between the Australian Board of Control and the M.C.C. in England. The Australian Board said Bodyline was unsportsmanlike and dangerous. The M.C.C. responded angrily. They threatened to stop the tour. The series became a big problem between the two countries. Many people thought Bodyline was hurting their relationship. The Governor of South Australia worried about trade. The problem was solved when Australian Prime Minister Joseph Lyons met the Australian Board. He explained the economic problems if British people stopped buying Australian goods. The Board withdrew their accusation.

Jardine was shaken by these events. Stories appeared in the press about fights among the England players. Jardine offered to stop Bodyline if his team did not support him. But after a private meeting, the players said they fully supported Jardine and Bodyline. Some players had private doubts, but they did not say so publicly.

England won the fourth Test to win the series. Eddie Paynter scored 83 after leaving the hospital. Jardine scored a very slow 24. He faced 82 balls without scoring a single run. England also won the final Test. In this match, Jardine and Larwood had a final disagreement. Larwood was angry when Jardine sent him in to bat as nightwatchman. Larwood scored 98 runs. Later, Larwood broke his foot while bowling. Jardine made him stay on the field until Bradman was out. Larwood never played another Test match. Also in this match, Jardine upset Harry Alexander by asking him not to run on the pitch. Alexander then bowled fast, short balls at Jardine, hitting him.

Jardine won the series as captain. But he scored only 199 runs at an average of 22.11 in the Tests. He scored 628 runs (average 36.94) in all first-class cricket in Australia. Jardine only played in the first Test of the short series in New Zealand due to illness. The players enjoyed the New Zealand tour. Pelham Warner, the manager, praised Jardine's captaincy. He believed Jardine was treated badly by Australian crowds.

Aftermath and Retirement

The Bodyline controversy continued into the next summer. Jardine wrote a book, In Quest for the Ashes. He defended his tactics and criticised the Australian crowds. He even suggested stopping matches between England and Australia. Jardine was welcomed as a hero in England. He was appointed England captain for the series against the West Indies in 1933. He continued to captain Surrey when he played. He was cheered by crowds when he batted. He scored 779 runs at an average of 51.93 that season, including three centuries.

The West Indies team tried Bodyline against England. Facing difficult short-pitched bowling, Jardine told his teammate, "You get yourself down this end, Les. I'll take care of this bloody nonsense." He faced the fast, short balls without flinching. Wisden said he played it "probably better than any other man in the world." He batted for almost five hours, scoring 127 runs. This was his only Test century. England then bowled Bodyline back at the West Indies. But the slow pitch meant the match was drawn. This performance helped turn English opinion against Bodyline.

During the 1933 season, Jardine was chosen as captain for the M.C.C. tour of India. This tour would have India's first Tests at home. Jardine was supported despite growing unhappiness about Bodyline. The M.C.C. leaders talked to Jardine about being diplomatic on the tour. The team was not full-strength, but won the Test series 2–0. India was weaker than expected. Wisden praised Jardine's captaincy and batting. He was very competitive. He was also more willing to give speeches than on the Bodyline tour. He showed respect for Indian crowds. He often spoke of his love for India. He seemed relaxed and happy on this tour.

England won the Test series 2–0. Jardine scored three half-centuries in four innings. He scored 221 runs at an average of 73.66. He scored 60, 61, and 65. His final Test innings was 35 not out. Jardine scored 831 first-class runs on the Indian tour.

There were still disagreements on the tour. He argued with the Viceroy over picking the Maharaja of Patiala for a match. He also complained that the pitch was rolled for too long. He clashed with umpire Frank Tarrant. Jardine threatened to stop Tarrant from umpiring. Tarrant, who had officiated the first two Tests, was not used in the third. Jardine mostly used different tactics than in Australia. Slow bowling was important. But sometimes, fast bowlers Nobby Clark and Stan Nichols bowled Bodyline. This caused some injuries. Indian bowlers Mohammad Nissar and Amar Singh bowled Bodyline back.

After the tour, there was talk about Jardine's future. The M.C.C. knew Bodyline was dangerous and should stop. Australians wanted guarantees that Jardine would not use Bodyline. Plum Warner also thought Jardine should no longer be captain. Jardine made the decision himself. In March 1934, he told Surrey he could not play regularly anymore. He resigned as captain. Then he announced that he would not play cricket against Australia that summer. It is not clear if this was due to pressure over Bodyline or financial worries. This decision ended his first-class career. He never played another Test. He played only two more first-class matches in England and one in India.

Jardine played in 22 Test matches for England. He scored 1,296 runs at an average of 48.00. In his first-class cricket career, he played 262 matches. He scored 14,848 runs at an average of 46.83. His occasional bowling took 48 wickets at an average of 31.10.

Cricket Style and Personality

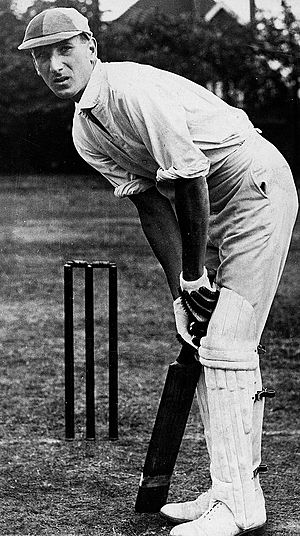

Batting Style

Jardine had a classic batting style. He stood very straight and sideways to the bowler. His hits to the off-side were powerful. His defence was excellent. He was great at judging the ball's line and letting it pass if it would miss his wickets. His play on the on-side was also excellent. He could place the ball between fielders for easy runs.

Jardine was described as a traditional amateur player. But his batting approach was like a professional. His back-foot batting was very high quality. Wisden said in 1928 that Jardine was the most secure amateur batsman. His greatest strengths were his defence and his "mental gifts." He played very straight. He could not play all the strokes, especially on the off side. R. C. Robertson-Glasgow thought Jardine copied C. B. Fry. He also noted Jardine's good focus and fighting spirit. The more important the match, the more defensive Jardine's batting became.

Jardine liked to score runs when his team was in trouble. He enjoyed being challenged. His defensive style often helped his team recover from bad situations. He also did well in the important Gentlemen v Players matches. Jack Hobbs thought he was a great batsman and was underrated.

Wisden believed Jardine's good batting technique meant fast bowlers bothered him less than other batsmen. But a few bowlers did cause him trouble. Alec Kennedy took Jardine's wicket eleven times. Kennedy found Jardine's footwork a bit slow. Bert Ironmonger also troubled Jardine, taking his wicket five times in Tests. Jardine struggled a bit against Australian slow bowlers. He was out to slow bowlers ten times in 16 Test innings in Australia. But he rarely had problems against English spinners. The Australian fast bowler Tim Wall also caused Jardine problems.

Captaincy Skills

As a captain, Jardine inspired great loyalty in his players. This was true even if they did not agree with his tactics. He kept the team united on the Bodyline tour. Team spirit was always excellent. Players showed great determination. Jardine especially impressed players from Yorkshire. They thought he thought about cricket like them. He became close to Herbert Sutcliffe during the Bodyline tour. Hedley Verity was impressed by Jardine's tactics. Bill Bowes approved of his leadership after some early doubts. He called Jardine England's greatest captain. However, some players thought he was too strict. They felt he expected everyone to play at a world-class level.

Jardine demanded strict discipline from his players. In return, he took great care of them. He organised dental treatment and provided champagne for tired bowlers. Critics praised his skill in placing fielders. He also showed great physical courage. He was hit by a ball hard enough to draw blood on the Bodyline tour. But he refused to show pain until he reached the dressing room. On the same tour, he told his players not to be friendly with Australian players. Gubby Allen even said Jardine told the team to hate the Australians.

Robertson-Glasgow wrote that Jardine prepared thoroughly for games. He studied individual batsmen to find their weaknesses. He had clear plans. He knew how to get the best out of players. However, Robertson-Glasgow thought it was a big mistake to make Jardine England captain. This was because of his known dislike for Australia. Pelham Warner said Jardine "was a master of tactics and strategy." He was especially good at managing fast bowlers. He also said Jardine was "surpassed by no one and equalled by few" as a field tactician.

Laurence Le Quesne said Jardine's greatest talent and weakness was his ability to plan a winning strategy. He did this without thinking about other things, like the social side of the game. On the Bodyline tour, he ignored the need for diplomacy. Instead, he wanted to win and settle personal scores with Australians. Jardine could not react to the crowds or the controversy in a way that would calm things down. So, he was not a good choice as captain, given what selectors already knew about him. But Le Quesne believed that when trouble happened, Jardine acted with "great moral courage and an impressive degree of dignity."

In his Wisden obituary, Jardine was called one of England's best captains. Jack Hobbs rated him the second best captain after Percy Fender. Warner also said he was a fine captain. He stated, "If ever there was a cricket match between England and the rest of the world and the fate of England depended upon its result, I would pick Jardine as England captain every time."

Personality Traits

Jardine was a complex person. He could be charming and funny, or tough and harsh. Many people who knew him thought he was shy. David Frith said he could change moods quickly. He could be friendly off the field, but became determined and serious during a match. At his memorial service, he was described as "provocative, austere, brusque, shy, humble, thoughtful, kindly, proud, sensitive, single-minded and possessed of immense moral and physical courage."

Harold Larwood respected Jardine greatly. He kept a gift Jardine gave him after the Bodyline tour. He believed Jardine was a great man. Jardine also showed affection for Larwood. He worried about how Larwood was treated. He hosted a lunch for Larwood before he moved to Australia. Donald Bradman never spoke to journalists about Bodyline or Jardine. He refused to give a tribute when Jardine died. Jack Fingleton said he liked Jardine. He felt both Jardine and Larwood did their jobs on the Bodyline tour. He regretted how both left cricket in bad circumstances. Fingleton also said Jardine was a distant person. He took his time to get to know someone before becoming friends. This caused problems in Australia. Bill O'Reilly said he disliked Jardine during Bodyline. But when he met him later, he found him pleasant.

Alan Gibson said Jardine had "irony rather than humour." He sent Herbert Sutcliffe an umbrella as a joke on the day of Sutcliffe's benefit match. Rain would have ruined the match and cost Sutcliffe a lot of money. Many people who knew Jardine later said he had a sense of humour. Robertson-Glasgow noted that Jardine disliked wasting things, including words. He also said, "if he has sometimes been a fierce enemy, he has also been a wonderful friend."

Later Life

Career After Cricket

Shortly before the India tour in 1933–34, Jardine got engaged. On 14 September 1934, he married Irene "Isla" Margaret Peat in London. His marriage was likely why he stopped playing first-class cricket. Jardine's father-in-law wanted him to work as a lawyer. But he continued as a bank clerk and became a journalist. He wrote about the 1934 Ashes series. His writing was critical of selectors but less so of players. In 1936, he wrote Cricket: how to succeed, a guide for teachers.

Changes to cricket rules in 1935, like the lbw law, prevented Bodyline bowling. Jardine became less interested in top-level cricket. He disliked the strong national feelings in Tests. He also disliked the focus on individual players like Bradman. At the same time, cricket writers seemed to ignore Jardine. Wisden did not even mention his retirement. Some believe Jardine was blamed for Bodyline after the M.C.C. stopped supporting it. He faced criticism for the rest of his life.

Although Jardine stopped regular first-class cricket, he still played club cricket. Jardine and his wife first lived in Kensington. They moved to Reading after their first daughter, Fianach, was born. They had a second daughter, Marion. The family faced money problems. Jardine earned money from journalism and playing bridge. The family also tried market gardening, but it did not work out. To earn more, Jardine became a salesman. In 1939, he returned to cricket journalism.

During World War II

Jardine joined the Territorial Army in August 1939. When World War II began, he became an officer in the Royal Berkshire Regiment. He went with the British Expeditionary Force to France. He served at Dunkirk, where he was lucky to escape. He suffered some injuries. After serving in St. Albans, he was sent to India for the rest of the war. He served in Quetta and Simla. He became a major. He learned the Hindustani language. He gave lectures and played some cricket in India. He left the army in 1945. His job with the coal mining company was no longer available.

His wife had moved to Somerset. In 1940, she gave birth to a son, Euan, who had many health problems. In 1943, they had a third daughter, Iona. When Jardine returned from the war, the family moved to Radlett. Jardine found a job with paper manufacturers Wiggins Teape. In 1946, Jardine played for Old England in a charity match. He showed his old batting skill. By 1948, Jardine was more accepted in the cricket world. This was partly because English people saw Australian fast bowlers Ray Lindwall and Keith Miller as aggressive. England's poor performance in the 1946–47 and 1948 Ashes also made writers remember Jardine more fondly.

Final Years

In 1953, Jardine started journalism again for the Ashes series. He thought highly of Len Hutton's captaincy. He also did some broadcasting and wrote short stories to earn more money. His wife was in poor health, and medical care was expensive. In the same year, he became the first President of the Umpires Association. From 1955 to 1957, he was President of the Oxford University Cricket Club. In 1953, he travelled to Australia. He was surprised to be well received there. He said he was seen as "an old so-and-so who got away with it."

In 1957, Jardine travelled to Rhodesia. While there, he became ill. Tests showed he had advanced lung cancer. After some treatment, he went to a clinic in Switzerland with his wife. But the cancer had spread. He died in Switzerland on 18 June 1958. His ashes were scattered in Scotland. His family had asked about scattering his ashes at Lord's, but this was only for war dead. When he died, his estate was worth over £71,000. This would be worth around £1,765,000 in 2022.

Legacy

Jardine is always linked to Bodyline. John Arlott wrote in 1989 that "among Australians, Douglas Jardine is probably the most disliked of cricketers." To English people, his name means determination and disdain for crowds. To Australians, it means snobbishness and arrogance. Some argue that Bodyline was needed to overcome the advantage batsmen had at the time.

After the Bodyline tour, cricket writer Gideon Haigh said Jardine was seen as "the most reviled man in sport." This view changed from the 1950s. More recently, Jardine has been seen more kindly. In 2002, England captain Nasser Hussain was compared to Jardine as a compliment. This happened when he showed ruthlessness against opponents.

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |