Sea otter facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sea otter |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Wrapped around kelp in Morro Bay, California. | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: |

Enhydra

|

| Binomial name | |

| Enhydra lutris (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

|

Sea otters (Enhydra lutris) are amazing marine mammals. They live along the Pacific coast of North America. Long ago, they also lived in places like the Bering Strait, Kamchatka, and even as far south as Japan.

Sea otters have incredibly thick fur, with up to 165,000 hairs per square centimeter! People used to hunt them for this rich fur, almost causing them to disappear completely. By the time the 1911 Fur Seal Treaty protected them, there were so few left that hunting them was no longer worth it. Sea otters love to eat shellfish and other small sea creatures. Their favorite foods include clams, abalone, and sea urchins.

These clever otters often carry a special rock in their paws or in a pouch under their forearm. They use this rock to smash open shells to get to the yummy food inside. This makes them one of the few animals known to use tools! Sea otters can grow to be about 1 to 1.5 meters (3.3 to 4.9 feet) long and weigh around 30 kilograms (66 pounds). Even though they were once almost gone, their numbers have started to grow again, especially in California and Alaska. Sea otters are actually one of the smallest mammals living in the ocean.

Contents

About Sea Otters

The sea otter is one of the smallest marine mammals. But it is the heaviest animal in the weasel family (mustelids). Male sea otters usually weigh between 22 and 45 kg (49 to 99 lb). They are about 1.2 to 1.5 meters (3.9 to 4.9 ft) long. Females are a bit smaller, weighing 14 to 33 kg (31 to 73 lb) and measuring 1.0 to 1.4 meters (3.3 to 4.6 ft) long.

Unlike most other marine mammals, sea otters do not have blubber (a layer of fat) to keep warm. Instead, they rely on their super thick fur. Their fur is the densest of any animal, with up to 150,000 hairs per square centimeter. This fur has long, waterproof guard hairs and a short, dense underfur. The guard hairs keep the underfur dry. This way, cold water stays completely away from their skin, and they lose very little heat.

Their fur stays thick all year. It sheds and grows back slowly, not all at once. To keep their fur working perfectly, sea otters spend a lot of time grooming. They can reach and clean almost any part of their body. Their skin is loose, and their skeleton is very flexible. Sea otters are usually deep brown with silver-gray spots. But their fur can also be yellowish, grayish brown, or almost black. Adult otters often have lighter fur on their head, throat, and chest.

How Sea Otters Are Built for the Ocean

Sea otters have many special features that help them live in the ocean. Their nostrils and small ears can close tightly. Their back feet are long, flat, and fully webbed. These feet help them swim fast. The longest toe on each back foot helps them swim while floating on their back. But it makes walking on land a bit clumsy.

Their tail is short, thick, and muscular. It is also slightly flat. Their front paws are short with claws that can pull back. The tough pads on their palms help them grip slippery prey. Their bones are very dense, which helps them sink underwater more easily.

Sea otters move underwater by wiggling their back end, tail, and hind feet up and down. They can swim up to 9 km/h (5.6 mph). When underwater, their body is long and smooth. Their front paws are held close to their chest. When they are on the surface, they usually float on their back. They move by sculling their feet and tail from side to side. When resting, they can fold all four limbs onto their body to stay warm. On very hot days, they might hold their back feet underwater to cool down.

Sea otters float easily because they have large lung capacity. Their lungs can hold about 2.5 times more air than land mammals of the same size. Also, the air trapped in their fur helps them float. On land, sea otters walk with a clumsy, rolling movement. They can also run by bounding.

Sea Otter Senses

Sea otters have long, very sensitive whiskers and front paws. These help them find food by touch, especially when the water is dark or cloudy. Researchers have noticed that otters react faster to people when the wind blows towards them. This means their sense of smell is very important for warning them of danger.

Their sight is useful both above and below water, but it is not as good as a seal's. Their hearing is average, neither super good nor super bad.

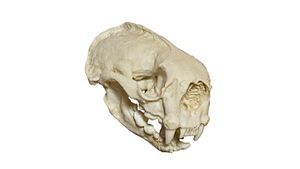

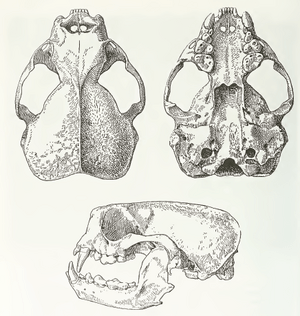

An adult sea otter has 32 teeth. Their molars are flat and round, perfect for crushing food instead of cutting it. Sea otters and seals are the only carnivores with two pairs of lower incisor teeth instead of three. Sometimes, their teeth and bones turn purple from eating too many sea urchins!

Sea Otter Behavior

Sea otters are active during the day (this is called diurnal). They usually start looking for food and eating about an hour before sunrise. Then, they rest or sleep in the middle of the day. They start foraging again for a few hours in the afternoon, stopping before sunset. Sometimes, they might have a third foraging time around midnight. Mothers with pups often feed more at night. Sea otters spend between 24% and 60% of their day looking for food. This depends on how much food is available.

Sea otters spend a lot of time grooming their fur. This means cleaning it, untangling knots, removing loose fur, rubbing it to squeeze out water, and blowing air into it. It might look like they are scratching, but they do not usually have lice or other bugs in their fur. When they eat, sea otters often roll in the water. This helps wash food scraps off their fur.

How Sea Otters Find Food

Sea otters hunt by making short dives, often going all the way to the sea floor. They can hold their breath for up to five minutes. But their dives usually last about one minute, and no more than four. They are the only marine animal that can lift and turn over rocks. They often do this with their front paws when searching for prey. Sea otters also pluck snails and other creatures from kelp. They can even dig deep into underwater mud for clams. They are the only marine mammal that catches fish with their front paws instead of their teeth.

Under each front leg, a sea otter has a loose pouch of skin that stretches across its chest. They use this pouch (usually the left one) to store food they collect. This way, they can bring it to the surface. This pouch also holds a special rock that the otter uses to break open shellfish and clams. At the surface, the sea otter floats on its back and eats. It uses its front paws to tear food apart and bring it to its mouth. They can chew and swallow small mussels with their shells. But they might twist apart larger mussel shells. They use their lower incisor teeth to get the meat out of shellfish.

To eat large sea urchins, which are mostly covered with sharp spines, the sea otter bites the soft underside where the spines are shortest. Then, they lick the soft insides out of the urchin's shell.

Sea otters use rocks when they hunt and eat. This makes them one of the few mammal species that use tools. To open hard shells, they might pound their prey with both paws against a rock on their chest. To pull an abalone off its rock, they hit the abalone shell with a large stone. They have been seen hitting it 45 times in just 15 seconds! It takes many dives to get an abalone, as it can stick to a rock with a force 4,000 times its own body weight.

Sea Otter Social Life

Even though adult and young sea otters usually hunt alone, they like to rest together in groups called "rafts." These rafts are usually made up of otters of the same sex. A raft typically has 10 to 100 animals. Male rafts are usually larger than female ones. The biggest raft ever seen had over 2,000 sea otters! To keep from floating away while resting and eating, sea otters sometimes wrap themselves in kelp.

A male sea otter is more likely to find a mate if he has a special breeding area. This area is usually one that females also like. Autumn is the busiest time for breeding in most places. So, males usually defend their area only from spring to autumn. During this time, males patrol their territory to keep other males out. But actual fights are rare. Adult females can move freely between male territories. There are usually about five females for every male. Males who do not have territories often gather in large, male-only groups. They swim through female areas when they are looking for a mate.

Sea otters make different sounds. A baby otter's cry often sounds like a seagull. Females make soft cooing sounds when they are happy. Males might grunt instead. Adult otters that are scared or upset might whistle, hiss, or even scream. Even though sea otters can be playful and friendly, they are not truly social animals. They spend a lot of time alone. Each adult can find its own food, groom itself, and protect itself.

Reproduction and Lifecycle

Baby sea otters can be born at any time of the year. But there are more births between May and June in northern areas. In southern areas, more births happen between January and March. Pregnancy can last from four to twelve months. This is because the species can delay the baby's growth before it starts developing fully for four months. In California, sea otters usually have babies every year. This is about twice as often as those in Alaska.

Birth usually happens in the water. Most often, a single pup is born, weighing about 1.4 to 2.3 kg (3 to 5 lb). Twins happen in only 2% of births. Usually, only one pup survives if twins are born. At birth, the pup's eyes are open, and it has ten teeth. It also has a thick coat of baby fur. Mothers have been seen licking and fluffing a newborn for hours. After grooming, the pup's fur holds so much air that it floats like a cork and cannot dive underwater. This fluffy baby fur is replaced by adult fur after about 13 weeks.

Baby otters drink their mother's milk (this is called nursing) for six to eight months in California. In Alaska, it can be four to twelve months. The mother starts giving the pup bits of prey when it is one to two months old. The milk from a sea otter's two belly nipples is very rich in fat. It is more like the milk of other marine mammals than that of other mustelids.

With its mother's help, a pup practices swimming and diving for several weeks. Eventually, it can reach the sea floor. At first, the things it finds are not very good to eat, like brightly colored starfish and pebbles. Young otters are usually able to live on their own at six to eight months old. But a mother might have to leave her pup if she cannot find enough food for both of them. On the other hand, a pup might keep nursing until it is almost adult size. Many pups do not survive, especially during their first winter. One estimate says only 25% of pups live past their first year. Pups born to experienced mothers have the best chance of survival.

Female otters do all the work of feeding and raising their babies. They have even been seen taking care of pups that lost their mothers. People have written a lot about how much sea otter mothers love their pups. A mother gives her baby almost constant attention. She holds it on her chest to keep it out of the cold water. She also carefully grooms its fur. When she goes to find food, she leaves her pup floating on the water. Sometimes, she wraps it in kelp so it does not float away. If the pup is not sleeping, it cries loudly until she comes back. Mothers have even been known to carry their pups for days after they have passed away.

In the wild, sea otters can live up to 23 years old. But they usually live 10–15 years for males and 15–20 years for females. Some otters in zoos have lived past 20 years. A female at the Seattle Aquarium lived to be 28 years old. Wild sea otters often have worn-down teeth, which might be why they do not live as long.

Images for kids

-

A mother floats with her pup on her chest. Georg Steller wrote, "They embrace their young with an affection that is scarcely credible."

-

Sea otters control herbivore populations, ensuring sufficient coverage of kelp in kelp forests

-

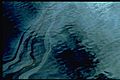

In the wake of the March 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, heavy sheens of oil covered large areas of Prince William Sound.

-

Sea otters off the coast of Washington, within the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary

See also

In Spanish: Nutria marina para niños

In Spanish: Nutria marina para niños