Friedrich Wöhler facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

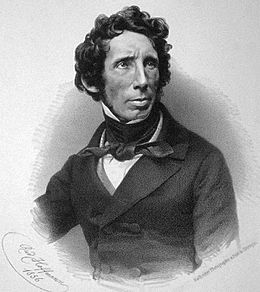

Friedrich Wöhler

|

|

|---|---|

Friedrich Wöhler (Catalan) 1856, age 56

|

|

| Born | 31 July 1800 Eschersheim, Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Died | 23 September 1882 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Organic chemistry Cocrystal Isomerism Wöhler synthesis Wöhler process |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 15 |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1872) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Organic chemistry Biochemistry |

| Institutions | Polytechnic School in Berlin Polytechnic School at Kassel University of Göttingen |

| Doctoral advisor | Leopold Gmelin Jöns Jakob Berzelius |

| Doctoral students | Heinrich Limpricht Rudolph Fittig Adolph Wilhelm Hermann Kolbe Georg Ludwig Carius Albert Niemann Vojtěch Šafařík Carl Schmidt Bernhard Tollens Theodor Zincke |

| Other notable students | Augustus Voelcker Wilhelm Kühne James Curtis Booth |

Friedrich Wöhler (born July 31, 1800 – died September 23, 1882) was an important German chemist. He is famous for his work in both organic chemistry and inorganic chemistry. He was the first to get the pure metals beryllium and yttrium. He also made several new inorganic compounds, like silane.

Wöhler is also well-known for his big discoveries in organic chemistry. His most famous work is the Wöhler synthesis of urea. He made urea, which is an organic compound, in his lab from things that were not alive. This went against the old idea that organic compounds could only come from living things because of a "life force." However, some people think his role in changing this belief might be a bit overstated.

Contents

Biography: A Chemist's Journey

Friedrich Wöhler was born in Eschersheim, Germany. His father was a veterinarian. As a young boy, Wöhler loved collecting minerals, drawing, and science. He went to high school at the Frankfurt Gymnasium. During this time, he started doing chemistry experiments in a lab his father set up at home. He began his college studies at Marburg University in 1820.

In 1823, Wöhler became a Doctor of Medicine, Surgery, and Obstetrics. He had studied in the lab of chemist Leopold Gmelin at Heidelberg University. Gmelin told him to focus on chemistry. He also helped Wöhler go to Stockholm, Sweden, to do research with the famous chemist Jacob Berzelius. Wöhler's time with Berzelius was the start of a long friendship and working relationship. Wöhler even translated some of Berzelius's science papers into German. Wöhler wrote about 275 scientific papers in his lifetime.

From 1826 to 1831, Wöhler taught chemistry at the Polytechnic School in Berlin. Then, from 1831 to 1836, he taught at the Polytechnic School in Kassel. In 1836, Wöhler became a chemistry professor at the University of Göttingen. He worked there for 46 years until he died in 1882. About 8,000 students learned chemistry in his lab during his time at Göttingen. In 1834, he became a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Wöhler's Chemical Discoveries

Working with Inorganic Elements

Wöhler studied more than 25 different chemical elements during his career. In 1825, Hans Christian Ørsted was the first to separate the element aluminium. He used a method that involved aluminium chloride. Wöhler improved Ørsted's method. He used potassium metal instead of potassium amalgam to get pure aluminium. On October 22, 1827, Wöhler got pure aluminium powder. In 1845, he showed that this powder could be turned into solid balls of pure aluminium. Because of this, Wöhler is known for being the first to get pure aluminium metal.

In 1828, Wöhler was the first to get pure beryllium metal. He also got pure yttrium metal that same year. He did this by heating the dry chlorides of beryllium and yttrium with potassium metal.

In 1850, Wöhler found that what people thought was pure titanium was actually a mix of titanium, carbon, and nitrogen. He then made the purest form of titanium known at that time. He also found ways to make calcium carbide and silicon nitride.

Wöhler worked with French chemist Sainte Claire Deville. Together, they got boron in a crystal form. He also got silicon in a crystal form. These crystal forms had not been seen before. In 1856, Wöhler and Heinrich Buff made the inorganic compound silane (SiH4). He also made the first samples of boron nitride.

Wöhler was also interested in the chemicals found in meteorites. He showed that some meteorites have organic matter in them. He studied many meteorites and wrote about them for years. He collected one of the best private collections of meteorites.

Big Steps in Organic Chemistry

In 1832, Wöhler worked with Justus Liebig in his lab in Giessen. They studied the oil from bitter almonds. They found that a group of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms could act like a single atom. This group could take the place of an atom in a chemical compound. This idea was called "compound radicals." It greatly helped the study of organic chemistry. Many other similar groups, called functional groups, were found later.

Liebig and Wöhler also looked into chemical isomerism. This is the idea that two different chemical compounds can have the exact same atoms, but arranged differently. This different arrangement makes them different substances. They studied silver fulminate and silver cyanate. These two compounds have the same chemical makeup. But silver fulminate explodes, while silver cyanate is stable. Wöhler and Liebig realized these were examples of structural isomerism. This was a big step in understanding how chemicals are built.

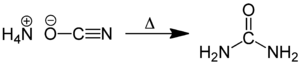

Wöhler is also seen as a pioneer in organic chemistry because of his 1828 discovery. He showed how to make urea in the lab from ammonium cyanate. This chemical reaction is now called the "Wöhler synthesis." Urea and ammonium cyanate are also examples of structural isomers. Heating ammonium cyanate turns it into urea. Wöhler wrote to his friend, chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius, saying he could make urea "without the use of kidneys of any animal."

Wöhler's work on urea was seen as proof against vitalism. This was a belief that living things had a special "vital force" that made them alive. It also suggested that only living things could make "organic" compounds. Wöhler's discovery helped end this idea. Berzelius himself said Wöhler's findings were very important for understanding organic chemistry.

Over time, Wöhler's role in ending vitalism has sometimes been made to seem bigger than it was. Some historians say that later writers, like Hermann Kopp, focused too much on this part of his work. They sometimes ignored how important his work was for understanding chemical isomerism.

Changing How Chemistry is Taught

When Wöhler became a professor at the University of Göttingen, students came from all over the world to learn from him. Wöhler had great success with his students by letting them get hands-on experience in the lab. This way of teaching was later used around the world. Today, most universities require a chemistry lab class.

Wöhler also let his students help him with his research. This was not common at the time. This practice later became normal. Now, many college degrees require students to do their own research.

Lasting Impact and Legacy

Wöhler's discoveries greatly changed how people thought about chemistry. He published new scientific work almost every year from 1820 to 1881. A science magazine in 1882 said that "for two or three of his researches he deserves the highest honor a scientific man can obtain." It also said, "Had he never lived, the aspect of chemistry would be very different from that it is now."

Some of Wöhler's famous students were chemists like Georg Ludwig Carius, Heinrich Limpricht, and Augustus Voelcker.

Wöhler became a Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1854. He was also an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. In 1862, Wöhler became a member of the American Philosophical Society.

In 2005, Robin Keen wrote "The Life and Work of Friedrich Wöhler (1800–1882)." It is seen as the first detailed science biography of Wöhler.

On the 100th anniversary of Wöhler's death, the West German government made a stamp. It showed the chemical structure of urea and how Wöhler made it.

Family Life

Wöhler married his cousin, Franziska Maria Wöhler, in 1828. They had two children, a son named August and a daughter named Sophie. Franziska died in 1832. In 1834, he married Julie Pfeiffer. They had four daughters: Fanny, Helene, Emilie, and Pauline.

See also

In Spanish: Friedrich Wöhler para niños

In Spanish: Friedrich Wöhler para niños

- Benzoin condensation

- History of aluminium

- Stanley Miller

- Hilaire Marin Rouelle

- Kassel

- Structural Isomer

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |