Gordon Bunshaft facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gordon Bunshaft

|

|

|---|---|

Lever House, 1951-1952; Gordon Bunshaft at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing 999.

|

|

| Born | May 9, 1909 Buffalo, New York, US

|

| Died | August 6, 1990 (aged 81) New York City, US

|

| Alma mater | Massachusetts Institute of Technology (BA, MA) |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse(s) |

Nina Wayler

(m. 1943) |

| Awards | American Institute of Architects Twenty-five Year Award, elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters, Pritzker Architecture Prize |

| Practice | Skidmore, Owings & Merrill |

| Buildings | Lever House, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden |

Gordon Bunshaft (May 9, 1909 – August 6, 1990) was an important American architect. He was a leader in modern design during the mid-1900s. Bunshaft worked for a famous architecture firm called Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) for over 40 years.

Some of his most well-known buildings include Lever House in New York City and the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. He also designed the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. His buildings often featured new ideas like glass walls.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Gordon Bunshaft was born in Buffalo, New York. His parents were immigrants from Russia. As a child, he was often sick. He spent a lot of time drawing houses while in bed.

A doctor noticed his drawings and told his mother he should become an architect. He studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He earned both his bachelor's and master's degrees there. After college, he traveled and studied architecture in Europe.

Career Highlights

After his studies, Bunshaft worked briefly for other designers. In 1937, he joined Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). He stayed with the firm for 42 years. He took a break to serve in the Army during World War II.

Bunshaft was inspired by famous architects like Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. He saw Mies as the "Mondrian of architecture" and Le Corbusier as the "Picasso."

Lever House and Other Key Projects

One of his most famous buildings is the Lever House, completed in 1952. It was one of New York's first major buildings with a "glass curtain-wall." This means its outer walls were made mostly of glass. It looked very different from the older, solid buildings around it.

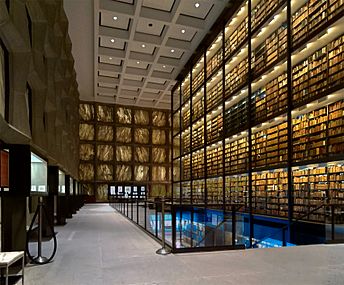

Other important buildings he designed include the Manufacturers Trust Company Building (1954). This was the first bank in the U.S. built in the modern International Style. He also designed the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University (1963). This library was designed to protect and display valuable books.

His only home was called the Travertine House. It was designed for art, not a family. He left it to a museum when he died. However, it was later sold and sadly torn down.

Awards and Recognition

Gordon Bunshaft received many important awards for his work. In 1988, he won the Pritzker Architecture Prize. This is one of the highest honors an architect can receive.

He also received the American Institute of Architects Twenty-five Year Award for Lever House in 1980. This award recognizes buildings that have stood the test of time. He was also a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters.

Architectural Style

Bunshaft is praised for starting a new era of skyscraper design. His first major project, Lever House, was a great example of this. It showed how buildings could be modern and sleek.

Later in his career, his designs became more "sculptural." This means they had more artistic shapes and forms. The Beinecke Library at Yale is an example. It's a large box with a central book tower. It uses translucent marble framed in granite, making it look like a work of art.

Bunshaft was known for being a man of few words. He famously said he wanted his buildings to speak for themselves.

Buildings Designed by Gordon Bunshaft

- 1942 – Great Lakes Naval Training Center, Hostess House – Great Lakes, Illinois

- 1951 – Lever House – New York City

- 1952 – Manhattan House – New York City

- 1953 – Manufacturers Trust Company Building – New York City

- 1956 – Ford World Headquarters – Dearborn, Michigan

- 1956 – Consular Agency of the United States, Bremen – Bremen, Germany

- 1957 – Connecticut General Life Insurance Company Headquarters – Bloomfield, Connecticut

- 1955 – Istanbul Hilton – Istanbul, Turkey

- 1958 – Reynolds Metals Company International Headquarters – Richmond, Virginia

- 1960 – 500 Park Avenue (Pepsi-Cola Company World Headquarters) – New York City

- 1961 – 28 Liberty Street (Chase Manhattan Bank) – New York City

- 1962 – CIL House – Montreal, Quebec

- 1962 – Albright-Knox Art Gallery addition – Buffalo, New York

- 1963 – Travertine House – East Hampton, New York

- 1963 – Beinecke Library – Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

- 1965 – American Republic Insurance Company Headquarters – Des Moines, Iowa

- 1965 – Banque Lambert – Brussels, Belgium

- 1965 – Heinz Corporate Headquarters – Hillingdon, England

- 1965 – New York Public Library for the Performing Arts (interiors) – New York City

- 1965 – Hayes Park Central & South Buildings – Hayes, United Kingdom

- 1965 – Warren P. McGuirk Alumni Stadium – University of Massachusetts , Amherst, Massachusetts

- 1967 – 140 Broadway – New York City

- 1970 – American Can Company Headquarters – Greenwich, Connecticut

- 1971 – Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum – Austin, Texas

- 1972 – Carborundum Center – Niagara Falls, New York

- 1972 – Carlton Centre – Johannesburg, South Africa

- 1973 – New York City Convention and Exhibition Center (not built) – New York City

- 1973 – Uris Hall, Cornell University – Ithaca, New York

- 1974 – Solow Building – 9 West 57th Street, New York City

- 1974 – W. R. Grace Building – New York City

- 1974 – Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden – Washington, D.C.

- 1983 – National Commercial Bank – Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Personal Life

In 1943, Bunshaft married Nina Wayler. They were both big fans of modern art. They collected many important artworks by artists like Joan Miró and Dubuffet.

They lived in the Manhattan House Apartments in New York. Bunshaft helped design these apartments. They also had their home, the Travertine House, in East Hampton. Gordon Bunshaft passed away in 1990 at the age of 81.

Images for kids

-

Exterior of the Hirshhorn Museum, facing Independence Avenue

-

The LBJ Presidential Library in Austin, Texas

Gallery

-

Manufacturers Trust Building

New York City 1954 -

Connecticut General Life Insurance Headquarters

Bloomfield, CT 1957 -

Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York 1962

-

Johnson Presidential Library

Austin, Texas, 1971 -

Solow Building

New York, 1974 -

Hirshhorn Museum

Washington, D.C. 1974

See also

In Spanish: Gordon Bunshaft para niños

In Spanish: Gordon Bunshaft para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |