Ham Wall facts for kids

Ham Wall is a special wetland area in England. It's a National Nature Reserve (NNR) located about 4 kilometres (2.5 miles) west of Glastonbury in the Somerset Levels. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) takes care of this important place.

For thousands of years, after the last Ice Age, dead plants in the marshes of the River Brue valley slowly turned into thick layers of peat. In the 1900s, people dug up a lot of this peat for gardening. When the demand for peat went down, the landowners, Fisons, gave their old peat workings to Natural England in 1994. Natural England then asked the RSPB to manage the 260-hectare (640-acre) Ham Wall area.

Ham Wall was created to be a home for the Eurasian bittern, a type of bird that was almost gone from the UK. The reserve is split into different parts, and the water levels in each part can be controlled. Special machines and even cattle help keep the reed beds healthy. Many rare wetland birds, like the little bittern and great white egret, now live and breed here. Other unusual animals and plants also call Ham Wall home. The RSPB works with other groups in the Avalon Marshes Partnership to protect nature across the Somerset Levels.

You can visit Ham Wall all year round. It has walking trails, bird hides, and viewing spots. The reserve is part of a bigger protected area called the Somerset Levels NNR. It's also a Ramsar site and a Special Area of Conservation, which means it's important for wetlands and wildlife worldwide. Future challenges might include heavy rains and floods due to climate change, which could make it harder to manage the water levels.

Contents

The Landscape of Ham Wall

About 10,000 years ago, after the last Ice Age, the melting glaciers caused sea levels to rise. The river valley that is now the Somerset Levels slowly became a salt marsh. Around 6,500 to 6,000 years ago, these marshes turned into reed beds with rhynes (ditches) and open water. Some areas even became wet woodlands.

When plants died in this watery, oxygen-poor environment, they didn't fully rot away. Instead, they formed layers of peat. Over time, these layers built up to create a huge raised bog. This bog might have covered 680 square kilometres (260 square miles) during Roman times! The bog grew because the Somerset Levels get a lot of rain, especially from the nearby Mendip Hills and Blackdown Hills. Also, thick layers of marine clay underneath the peat stopped water from draining away. This clay is so good at holding water that the peat layers can be up to 7.3 metres (24 feet) thick in some places.

A Look Back in Time

People have lived in the Somerset Levels since the Neolithic period, about 6,000 years ago. They used the reed swamps for resources and built wooden trackways, like the famous Sweet Track and Post Track. During the Romano-British period, people extracted salt here.

In the Middle Ages, much of the land was owned by the church. They drained large areas and changed the paths of rivers. However, the raised bogs mostly stayed untouched. It wasn't until the 1700s, with laws called the Inclosure Acts, that a lot of the peat bogs were drained. Even then, the River Brue often flooded the land in winter. After 1801, parts of the Brue were made straighter, and new channels were built to help with drainage.

The Glastonbury Canal, which goes through Ham Wall, opened in 1833. It was used to transport goods and people. Later, in 1854, a railway line was built next to it, making the canal less important. This railway, the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway, ran from Glastonbury to Highbridge and closed in 1966. Both the railway and the canal were important for moving peat.

By the 1900s, huge amounts of peat were being dug up in the Somerset Levels to meet the demand for gardening. Fisons, the company that owned the peat workings, was producing 250,000 tonnes (246,000 long tons) of peat each year in the early 1990s. When the demand for peat dropped, Fisons gave much of their land to English Nature (now Natural England) in 1994. This led to the creation of 13 square kilometres (5 square miles) of new wetland nature reserves. English Nature then asked the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) to manage 230 hectares (570 acres) at Ham Wall.

The reserve gets its name from the Ham Wall rhyne, a drainage channel that flows through the site. "Rhyne" is a local word for these channels. "Ham" is an old word for pasture or meadow. The Ham Wall might have been a bank to hold water on the flooded fields.

Creating the Reserve for Wildlife

The main reason Ham Wall reserve was created was to help the Eurasian bittern. In 1997, there were only 11 male bitterns left in the UK. Their reed bed homes were disappearing, and important coastal areas were at risk from saltwater floods. So, creating a new inland home for them was a great idea for the RSPB.

The old peat diggings already had bund walls (raised banks) that made it easy to control water levels in different parts of the reserve. The peat had been dug down to the underlying marine clay, which was about 2 metres (6.6 feet) deep in this area.

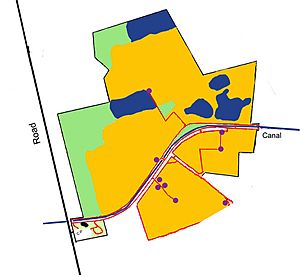

Water levels are managed using sluices (water gates), pipes, and wind-pumps. This creates reed beds with about 20% open water. The ditches were made deeper and wider to stop reeds from growing too much and to provide a home for fish, especially common rudd. These fish are food for the bitterns. By 2013, the 260-hectare (640-acre) reserve had 220 hectares (540 acres) of reed bed, including 75 hectares (190 acres) of deep water channels. It also has 10 hectares (25 acres) of wet woodland and 30 hectares (74 acres) of grass.

Ham Wall, along with Lakenheath Fen in Suffolk, has been key to a bittern recovery program started in 1994. Both reserves created lots of new reed beds, giving the bitterns more places to breed.

Visiting Ham Wall

The reserve is about 4 kilometres (2.5 miles) west of Glastonbury. You can get there by car from the small road between Meare and Ashcott. National Cycle Route 3 also runs nearby. The closest bus stop is in Ashcott, 4 kilometres (2.5 miles) away. The railway station in Bridgwater is 15 kilometres (9.3 miles) away. Natural England's Shapwick Heath NNR is just west of Ham Wall.

Ham Wall is open and free to enter all the time. There is a charge for the car park if you are not an RSPB member, and it closes at night. There are toilets and a small visitor centre that sells snacks. It's usually open only on weekends.

The main path at the reserve is the Ham Wall loop. It follows the north bank of the canal, crosses a bridge, and returns on a grass track. This loop is 2.7 kilometres (1.7 miles) long. A short path leads to the Avalon hide from the canal path. There are also two other circular walks, 1.7 kilometres (1.1 miles) and 1.3 kilometres (0.81 miles) long. A boardwalk connects these two trails. The reserve has two bird hides and six viewing platforms or screens. Dogs on leads are allowed on the Ham Wall loop, but only assistance dogs can go elsewhere. About 70,000 people visit the reserve every year.

How Ham Wall is Managed

The main way the reserve is managed is by cutting the reeds. This helps to keep the reed beds healthy and stops them from drying out. Two special machines are used: an amphibious Truxor tracked reed cutter for wet areas, and a faster Softrak for islands and drier spots. Native breeds of cattle also help by grazing the edges of the reed beds. The cut reeds are turned into a special compost that is sold for home use.

The RSPB is part of the Avalon Marshes Partnership. This group includes other organisations like the Somerset Wildlife Trust, Natural England, and the Environment Agency. They all work together to protect nature in the area. This partnership helps manage the wetlands on a large scale. They work on things like reed bed management, improving paths for walkers and cyclists, and providing visitor facilities. The Avalon Marshes Centre, run by Natural England, is also near Ham Wall.

Animals and Plants at Ham Wall

Birds of the Reed Beds

Bitterns were first confirmed to have bred at Ham Wall in 2008, after being seen there for several years. Now, the reserve usually has 18–20 breeding male bitterns, which is probably its maximum. Another 20 males live in other parts of the Avalon Marshes.

Ham Wall has also attracted three other types of herons that are starting to breed in the UK.

- The great white egret, which used to be rare, first bred here in 2012. Small numbers have nested every year since then.

- The little bittern has been present since 2009 and bred in 2010. It's a shy bird, so proving it breeds in such a large reed bed is hard. In spring 2017, at least six little bitterns were seen.

- The cattle egret started breeding elsewhere in Somerset in 2008. In 2017, six pairs tried to breed at Ham Wall, and four were successful. In January 2018, 30 cattle egrets were seen.

Other common wetland birds at Ham Wall include:

- Grey herons, some of which nest in the reed beds instead of trees.

- Garganeys (usually two to three pairs).

- Marsh harriers (three nesting females in 2017).

- Hobbies.

- Bearded tits.

- Cetti's, reed, and sedge warblers.

In winter, hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions, of common starlings gather at Ham Wall for an evening roost. It's a huge sight that attracts many visitors.

Rare birds that have visited the reserve recently include a collared pratincole and a whiskered tern in 2016. A singing male pied-billed grebe and a squacco heron were seen in 2013, and a blue-winged teal in 2012.

Other Animals and Plants

Otters live and breed at Ham Wall. Two artificial homes, called holts, have been placed in the reed beds for them. Water voles can also be found here. Grass snakes, three types of newts, common toads, and common frogs live throughout the Avalon Marshes. Non-native marsh frogs are also found at Ham Wall and nearby Shapwick Heath.

A new "eel pass" was built recently to help European eels enter the reserve from the nearby River Huntspill. Young eels might stay in the reserve for up to 20 years before going back to the sea to breed.

The wetlands are home to many invertebrates (animals without backbones). These include rare water molluscs like the shining ram's-horn snail and the depressed river mussel. Insects include the purple hairstreak, silver-washed fritillary, and scarlet tiger moth. Sadly, some insects like the marsh fritillary and narrow-bordered bee hawk-moth have disappeared from the area since the mid-1990s.

19 different types of dragonflies and damselflies have been seen at Ham Wall. This includes a huge group of thousands of four-spotted chasers resting together. The lesser silver water beetle lives in the wet woodland, and a very rare leaf beetle called Oulema erichsoni was found in 2015.

Besides the common reed that covers most of the marshes, other special plants found in the Brue valley wetlands include rootless duckweed, marsh cinquefoil, water violet, milk parsley, and round-leaved sundew.

Future Challenges

Changes in the UK climate could bring heavy summer rains. This would be bad for ground-nesting birds, insects, and other wildlife. While Ham Wall is inland and not directly threatened by saltwater like some coastal reserves, rising sea levels will make it harder to drain the Somerset Levels. The current water-pumping systems might not be enough.

Despite planning by the Environment Agency, there have been big floods on the Levels recently. In November 2012 and after Cyclone Dirk in winter 2013–2014, 6,900 hectares (17,000 acres) of farmland were underwater for over a month.

Water sports and recreation in other parts of the Levels could accidentally bring non-native species into the wetlands. Also, the large number of visitors, especially those coming to see the winter starling roost, can cause traffic jams on local roads.

Images for kids

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |