History of Marrakesh facts for kids

The history of Marrakesh is about a famous city in southern Morocco. This city is so important that the country of Morocco itself is named after it! Marrakesh has a long and exciting past, stretching back almost a thousand years.

It was founded around 1070 by the Almoravids, who made it the capital of their large empire. Later, the Almohad Caliphate also used Marrakesh as their main city starting in 1147. When the Marinids took over in 1269, they moved the capital to Fez. This made Marrakesh a regional capital for the south, and it often rebelled and became semi-independent.

In 1525, the Saadian rulers captured Marrakesh. After they took Fez in 1549, Marrakesh became the capital of a united Morocco once more. The city became very grand and beautiful under the Saadians. The Alawi rulers took Marrakesh in 1669. While they often lived there, Marrakesh wasn't their only capital, as Alawi sultans moved their courts between different cities.

Throughout its history, Marrakesh has had times of great glory. But it also faced many challenges like political fights, wars, hunger, and diseases. Much of the city was rebuilt in the 1800s. French troops conquered it in 1912, and it became part of the French protectorate of Morocco. After Morocco gained independence in 1956, Marrakesh remained an important part of the Kingdom of Morocco.

Marrakesh and Fez have always been rivals for the title of Morocco's leading city. The country often split into two parts, with Fez ruling the north and Marrakesh the south. Today, Rabat is the capital of modern Morocco. This choice was a compromise, so neither Marrakesh nor Fez would be more important than the other.

Contents

Founding the City of Marrakesh

The area around Marrakesh, south of the Tensift River, has been home to Berber farmers for thousands of years. Many ancient stone tools have been found here.

Before the Almoravids arrived in the mid-1000s, the region was ruled by the Maghrawa from Aghmat. The Almoravids conquered Aghmat in 1058. But their leader, Abu Bakr ibn Umar, soon decided Aghmat was too crowded. The Almoravids were originally Sanhaja Lamtuna tribesmen from the Sahara Desert. They wanted a new home that felt more like their desert lifestyle.

After talking with local tribes, they chose a neutral spot between two tribes. The Almoravids set up their tents on the west bank of the small Issil river. The area was open and empty, with "no living thing except gazelles and ostriches." A few kilometers north was the Tensift River. To the south was the large plain of Haouz, perfect for their animals. To the west was the fertile Nfis river valley, which would provide food for the city. They planted Date palms around their camp, as dates were a main food for the Lamtuna people.

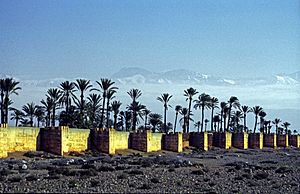

Historians disagree on the exact founding date. Some say it was around 1061-62, while others say 1070. It's likely that Marrakesh started in the 1060s as a military camp. The first stone building, a fort called Qasr al-Hajar (meaning "castle of stone"), was built in May 1070. In 1071, Abu Bakr's cousin, Yusuf ibn Tashfin, built the city's first brick mosque. More buildings followed, and mud-brick houses slowly replaced tents. The red earth used for the bricks gave Marrakesh its famous red color, earning it the name Marrakush al-Hamra ("Marrakesh the Red"). Early Marrakesh looked unique, like a sprawling desert city with tents, palm trees, and an oasis feel.

Sultan Ali ibn Yusuf ibn Tashfin built the first bridge over the Tensift River, connecting Marrakesh to northern Morocco. But the city's life was always linked to the south. The High Atlas mountains, south of the city, were very important. If enemies controlled the mountain passes, Marrakesh could be cut off from trade routes to the Sahara Desert. This trade in salt and gold was vital for the city's early wealth. The Almoravids built the city on the wide Haouz plain, away from the Atlas foothills, so they could see attackers coming from far away. This gave them time to prepare defenses. Still, throughout history, whoever controlled the High Atlas often controlled Marrakesh too.

Marrakesh as an Imperial Capital

Marrakesh became the capital of the huge Almoravid empire, which covered all of Morocco, western Algeria, and southern Spain (al-Andalus). Because of its dry surroundings, Marrakesh was mainly a political capital. It didn't immediately become a busy trade or learning center like Aghmat, which was only 30 kilometers away.

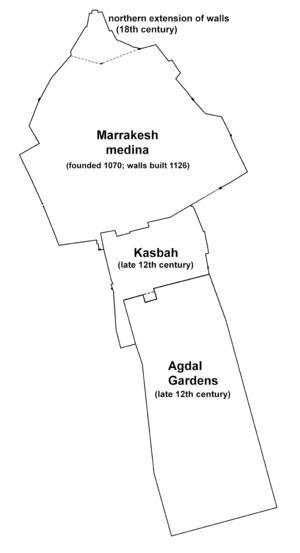

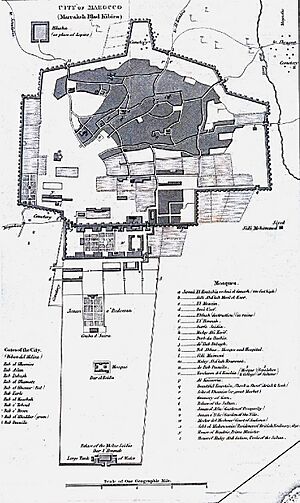

This began to change under the Almoravid leader Ali ibn Yusuf (who ruled from 1106-1142). He started a building program to make Marrakesh grander. Ali ibn Yusuf built a magnificent new palace with an Andalusian design. More importantly, he created a new water system using underground canals called khettaras. This system brought plenty of water to the whole city, allowing more people to live there. Ibn Yusuf also built several large ablution fountains and a grand new mosque, the Masjid al-Siqaya (the first Ben Youssef Mosque). This was the largest mosque in the Almoravid empire. The new mosque and the markets around it became the heart of city life. The rest of the city was organized into neighborhoods, with two main streets connecting four large gates: Bab al-Khamis (north), Bab Aghmat (southeast), Bab Dukkala (northwest), and Bab al-Nfis (southwest).

The new buildings and water supply began to attract merchants and craftsmen. The first to arrive were the tanners, who became famous for their leather. (Even today, goatskin leather is often called "Moroccan leather"). Industries like tanning, pottery, and dyeing were set up on the east side of town, across the Issil river. This was partly because of the smell and partly because they needed the river's water. Ali's irrigation system also allowed many new orchards, vineyards, and olive gardens to be planted. This attracted businesses that pressed oil, which were set up on the north side of town. Wealthy merchants and officials built beautiful city homes with Andalusian-style courtyards and fountains, known as riads.

Marrakesh started minting its own gold coins in 1092, showing its growing importance. Unlike other Moroccan cities, Jews were not allowed to live inside Marrakesh by Almoravid law. But Jewish merchants from Aghmat visited often, usually through the Bab Aylan gate. A temporary Jewish quarter was set up outside the city walls. Intellectual life was slower to develop. While religious scholars moved to Marrakesh, there were no large schools (madrasas) outside the palace. So, scholars preferred the lively learning centers of Fez, Cordoba, and even nearby Aghmat. A leper colony, the walled village of El Hara, was built northwest of the city. The city's earliest Sufi saint, Yusuf ibn Ali al-Sanhaji, was a leper.

Surprisingly, Marrakesh was not originally walled. The first walls were built only in the 1120s. Following advice from a wise man, Ali spent a lot of money to strengthen the city's defenses. This was because Ibn Tumart and the Almohad movement were becoming powerful. The walls were 6 meters (20 feet) tall, with twelve gates and many towers. They were finished just in time for the first attack by the Almohads. The Almohads were a new religious group from the High Atlas mountains. They attacked Marrakesh in early 1130 and besieged it for over a month. The Almoravids defeated them in the great Battle of al-Buhayra, which happened in the irrigated gardens east of the city.

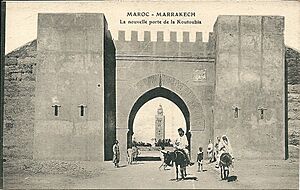

However, the Almoravid victory didn't last long. The Almohads regrouped and conquered the rest of Morocco. They finally returned to take Marrakesh in 1146. After an eleven-month siege, the Almohads climbed the walls in April 1147. They opened the gates and seized the city, finding the last Almoravid ruler in his palace. The Almohad Caliph Abd al-Mu'min refused to enter the city, claiming the mosques were facing the wrong way. The Almohads then destroyed all the Almoravid mosques so Abd al-Mu'min could enter. Today, only the ablution fountain of Koubba Ba'adiyin remains of Almoravid architecture, along with the city's main walls and gates (though these have been changed many times).

Even though the Almohads kept their spiritual capital in Tinmel, they made Marrakesh the new administrative capital of their empire. They built many grand structures here. On the ruins of the Almoravid palace, Abd al-Mu'min built the first Koutoubia Mosque. But he had it torn down shortly after, around 1157, because of an orientation error. The second Koutoubia mosque was probably finished by his son Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur around 1195. It had a magnificent and decorated minaret that stood tall over the city. Al-Mansur also built a fortified citadel, the Kasbah, just south of the main city (medina). The Bab Agnaou gate connected them. The Kasbah became the government center of Marrakesh for centuries, holding royal palaces, treasuries, and barracks. It also included a main mosque called the Kasbah Mosque. Sadly, nothing remains of the original Almohad palaces or al-Mansur's great hospital.

The Almohads also improved the water system. They built open-air canals (seguias) that brought water from the High Atlas mountains across the Haouz plain. These new canals allowed them to create the beautiful Menara Garden and Agdal Gardens to the west and south of the city.

Much of the Almohad architecture in Marrakesh was similar to buildings in Seville (their capital in Spain) and Rabat. Skilled workers from both sides of the straits created these buildings, using similar designs. For example, the Giralda of Seville and the (unfinished) Hassan Tower of Rabat are often compared to the Koutoubia. Under the Almohads, Marrakesh also became an important center for learning, attracting scholars like Ibn Tufayl and Ibn Rushd.

It was during the Almoravid and Almohad periods that Morocco got its name in other countries. Marrakesh was known in Europe as "Maroch" or "Marrochio." The Almohad empire was often called the "Kingdom of Marrakesh." Even into the 1800s, Marrakesh was sometimes called "Morocco city" by foreigners.

After the death of Yusuf II in 1224, the empire became unstable. Marrakesh became a stronghold for Almohad tribal leaders who wanted to take power from the ruling family. Marrakesh was captured and lost many times by different rulers. One notable event was when Caliph Abd al-Wahid II al-Ma'mun brutally seized Marrakesh in 1226. He then massacred the Almohad tribal leaders and their families.

Marrakesh as a Regional Capital

The internal struggles of the Almohads led to them losing control of Spain to Christian armies. A new dynasty, the Marinids, rose in northeast Morocco. By the 1260s, the Marinids had pushed the Almohads back to the southern areas around Marrakesh.

The Marinid leader Abu Yusuf Yaqub first tried to besiege Marrakesh in 1262, but failed. He eventually captured the city in September 1269. The remaining Almohads retreated to their stronghold in Tinmel and continued fighting until 1276.

The Marinids decided not to make Marrakesh their capital. Instead, they established their main city in Fez in the north. Marrakesh lost its status as an imperial capital and became just a regional center for the south. It was somewhat neglected as the Marinids focused on making Fez and other northern cities beautiful.

Even though the Almohads were no longer a political force, their religious ideas remained. Marrakesh was seen as a place of "heresy" by the orthodox Sunni Marinids. Marinid leader Abu al-Hasan built a few new mosques, including the Ben Saleh Mosque (1331). He also built Marrakesh's first madrasa (religious school) in 1343/9. This was part of the Marinids' effort to bring back Sunni Islam and the Malikite legal system, which had been important under the Almoravids.

Marrakesh didn't accept its reduced role easily. It often became a base for rebellions against the Marinid rulers in Fez. The Marinids sometimes used Marrakesh as a training ground for future rulers. But the city's past grandeur often encouraged these young princes to aim for more power. Many times, the governor of Marrakesh would rebel and declare independence from Fez.

Chaos returned after the death of Abd al-Aziz I in 1372. The Marinid empire effectively split in 1374, with one ruler in Fez and another in Marrakesh. But they fought, and by 1382, the ruler in Fez reconquered Marrakesh. After this, Marrakesh and its surrounding region became a semi-independent state, ruled by powerful local governors who were only loosely connected to the Marinid sultan in Fez.

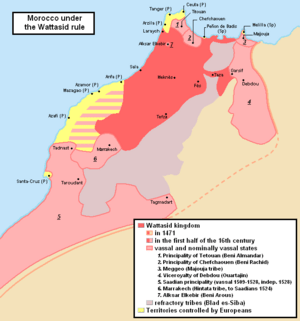

In 1415, the Christian Kingdom of Portugal attacked and seized Ceuta. This was the start of many Portuguese attacks on Morocco over the next century. Even though Marrakesh was independent, it helped the sultans of Fez fight against the Portuguese. After a failed attempt to retake Ceuta, the Marinid ruler was killed in 1420, and Morocco fell apart again. The Wattasids took power in Fez, but their authority didn't extend much beyond Fez. Marrakesh remained almost independent, ruled by local leaders.

Sufism, a mystical branch of Islam, became very popular in Morocco. Local Sufi saints, called marabouts, gained power as the Marinid central government weakened. One important Sufi leader was Muhammad ibn Sulayman al-Jazuli from the Sous region. He became famous in the mid-1400s. As a sharif (a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad), al-Jazuli gained support from people who missed the old Idrisid rulers.

In 1458, the Marinid ruler Abd al-Haqq II finally removed his powerful Wattasid advisors. The leaders of Marrakesh immediately rebelled. It's said that al-Jazuli, with 13,000 followers, crossed the Atlas mountains and set up Sufi centers (zawiya) all over the country, including many in Marrakesh. When Marinid agents killed Imam al-Jazuli in 1465, it led to an uprising in Fez that ended the Marinid rule. A new period of chaos followed. The Wattasids returned to power in Fez by 1472, but they couldn't control much beyond Fez. The leaders in Marrakesh were also limited, and much of the south fell into the hands of local Sufi marabouts.

The Portuguese took advantage of this disunity. They increased their attacks on Moroccan territory, not just in the north but also along the Atlantic coast, directly threatening Marrakesh. The Portuguese established bases in Agadir (1505), Souira Guedima (1507), and Safi (1508). They also seized Azemmour in 1513 and built a new fortress nearby. From Safi and Azemmour, the Portuguese made alliances with local Arab and Berber tribes. They sent armed groups inland, conquering the region of Doukkala and soon reaching Marrakesh. By 1514, the Portuguese and their allies were at the edge of Marrakesh. They forced the city's ruler to agree to pay tribute and allow them to build a fortress in Marrakesh. However, this agreement was not carried out. So, in 1515, the Portuguese and their allies returned with a strong army to take Marrakesh directly. But their army was defeated by a new force that had suddenly appeared from the south: the Saadian sharifs.

Marrakesh as the Saadian Capital

The Saadians were a respected sharifian family from the Draa valley. Around 1509-10, the Sufi groups in the Sous valley invited their leader, Abu Abdallah al-Qaim, to lead their holy war (jihad) against the Portuguese invaders. Al-Qaim led a successful campaign against the Portuguese in Agadir. He was soon recognized as a leader in Taroudannt in 1511, gaining the loyalty of the Sous tribes. In 1514, al-Qaim moved to Afughal, the spiritual center of the Sufi movement, at the invitation of the local Berbers. That same year, the Wattasid ruler of Fez blessed al-Qaim's jihad.

From Afughal, al-Qaim and his sons led attacks against Portuguese-held Safi and Azemmour. The Saadian army grew stronger over time. They were the ones who saved Marrakesh from the Portuguese attack in 1515. By the 1520s, the Portuguese had lost control of the surrounding areas and were confined to their fortresses.

Marrakesh, like many other Moroccan cities, suffered greatly during this time. Much of the city became empty due to famines in 1514 and 1515, caused by wars in the countryside, a drought in 1517, and bad harvests from 1520 to 1522. The traveler Leo Africanus described Marrakesh at this time, noting that "a great part of this city, lies so desolate and void of inhabitants." He also said that the grand palaces, gardens, and schools were "utterly void and desolate," taken over by wild animals. However, the Saadian Sharifs used their network of Sufi groups to provide food relief. This attracted hungry people from the north and greatly improved the Saadians' reputation.

Al-Qaim died in 1517, and his son Ahmad al-Araj took over. He moved to Marrakesh in 1524 to better lead operations. Al-Araj then seized the Kasbah and killed the local ruler. Al-Araj made Marrakesh the new Saadian capital. He also moved the remains of his father and the Imam al-Jazuli to Marrakesh.

The new Wattasid sultan of Fez, Ahmad al-Wattasi, was not happy. In 1526, he led a large army south to conquer Marrakesh, but he failed. After a battle, they agreed to the 1527 Treaty of Tadla. This treaty divided Morocco roughly along the Oum Er-Rbia River, with the Wattasids in Fez ruling the north and the Saadians in Marrakesh ruling the south. This peace didn't last long, and more battles were fought.

Relations between the Saadian brothers also broke down. In 1540-41, they led separate sieges. Ahmad al-Araj's siege failed, but Muhammad al-Sheikh captured Agadir in 1541. This victory caused the Portuguese to leave other areas, and the Saadians recovered Safi and Azemmour in 1542. Muhammad al-Sheikh's success increased his power. He soon challenged and defeated his brother, becoming the leader of the Saadian movement. He then expelled the Sufi leaders, who had been his brother's allies, from Marrakesh.

Muhammad al-Sheikh invaded Wattasid Fez in 1544/5, defeating and capturing the sultan. But the religious scholars in Fez refused to let him enter the city. Muhammad al-Sheikh had to besiege Fez and finally conquered it by force in September 1549. The Saadians then advanced east and took Tlemcen in 1550.

The Saadian success worried the Ottoman Turks, who had recently established themselves in nearby Algiers. The Ottomans supported the Saadians' enemies. With Ottoman help, the exiled Wattasid ruler was installed in Fez in early 1554. They also encouraged the deposed Saadian brother, Ahmad al-Araj, to try and retake Marrakesh. Muhammad al-Sheikh defeated his brother outside Marrakesh, then reconquered Fez by September 1554. To keep the Ottomans away, the Saadians made an alliance with Spain in 1555. However, Ottoman agents assassinated Muhammad al-Sheikh in 1557. His son, Abdallah al-Ghalib, faced challenges. The Ottomans went on the attack, capturing Tlemcen and invading the Fez valley in 1557. Al-Ghalib managed to defend against the Turkish attack in 1558. Because Fez was vulnerable to attacks from Ottoman Algeria, the Saadians decided to keep their court in safer Marrakesh. So, after more than two centuries, Marrakesh was restored as the capital of a united Morocco.

The Saadians worked hard to prove their right to rule. As sharifs, they claimed to be descendants of Muhammad. They tried to show their power and importance through grand buildings in Marrakesh.

Starting with Abdallah al-Ghalib, the Saadians rebuilt and decorated Marrakesh, turning it into a magnificent imperial city. They wanted it to rival the splendor of Ottoman Constantinople. Their biggest project was completely rebuilding the old Almohad Kasbah as their royal city. It included new gardens, palaces, barracks, a renovated El-Mansuria Mosque, and later, their burial ground, the Saadian Tombs. They also refurbished the Ben Youssef Mosque and built the grand new Ben Youssef Madrasa in 1564–65. This was the largest school in the Maghreb at the time. The Saadians built several new mosques, including the Bab Doukkala Mosque (1557–1571) and the Mouassine Mosque (1562–72).

The city's layout was changed. The city center moved from the Ben Youssef Mosque to the Koutoubia Mosque further west. The Jewish district, called the Mellah, was established around 1558 just east of the Kasbah. When Moriscoes (Muslims forced to convert to Christianity in Spain) were expelled from Spain in the early 1600s, a new quarter was built for them. The Saadians also built shrines for two important Sufi saints: the Zawiya of Sidi Ben Slimane al-Jazuli (around 1554) and the Zawiya of Sidi Bel Abbas al-Sabti (around 1605), who is the patron saint of Marrakesh.

After al-Ghalib's death in 1574, the Saadians had a family conflict over who would rule. After a famous victory against the Portuguese king in 1578, the new Saadian ruler, Ahmad al-Mansur (ruled 1578-1603), continued the building program in Marrakesh. He became known as al-Dhahabi ("the Golden") because of his grand projects. He built a lavish new palace for himself, the El Badi Palace (meaning "the Splendid"), which was a larger version of the Alhambra in Granada. He also raised a professional army and adopted the title of 'caliph'. Al-Mansur first paid for his grand lifestyle with ransoms from Portuguese prisoners and heavy taxes. When these ran out, he took control of the trans-Saharan trade routes. He then invaded and plundered the gold-rich Songhai Empire in 1590–91, temporarily bringing Timbuktu and Djenné into the Moroccan empire.

Things started to go wrong. A nine-year plague hit Morocco from 1598–1607, greatly weakening the country. Al-Mansur died in 1603. His successor, Abu Faris Abdallah, was recognized in Marrakesh, but his brother Zidan al-Nasir was chosen by the scholars of Fez. Zidan eventually won and entered Marrakesh in 1609. But then another brother revolted in the north, and Zidan was left with only Marrakesh. As Saadian power weakened, Morocco fell into chaos and split into smaller parts for much of the next century. Zidan was driven out of Marrakesh by a religious leader in 1612. He was restored only in 1614 with the help of another religious leader, who then tried to control the city himself. Zidan still found time to complete the Saadian Tombs at the Kasbah Mosque. However, there weren't enough resources to finish a grand Saadian mosque started by Ahmed al-Mansur. This unfinished site became known as the Jemaa el-Fnaa (Mosque of the Ruins), which is now the famous central square of Marrakesh.

While other parts of Morocco were taken by different groups, Marrakesh remained the main stronghold for a series of less important Saadian sultans. Their small southern kingdom only stretched from the High Atlas mountains to the Bou Regreg river. In 1659, the Shabana, an Arab tribe that was once part of the Saadian army, took control of Marrakesh. They killed the last Saadian sultan, and their leader declared himself the new sultan of Marrakesh.

Marrakesh as an Alawi City

In the 1600s, the Alawis, another sharifian family, established themselves in Tafilalet. After the death of their leader Ali al-Sharif in 1640, his son Muley Muhammad expanded their local power. Around 1659, one of Muhammad's brothers, Muley al-Rashid, left Tafilalet and eventually settled in Taza. He quickly gained control of a small area. Muley Muhammad confronted his brother but was defeated and killed in 1664. Al-Rashid then took over the family's lands and began a campaign to conquer the rest of Morocco.

Al-Rashid started his campaign from Taza in the north and entered Fez in 1666, where he was declared sultan. Two years later, he defeated the Dili marabouts who controlled the Middle Atlas. Muley al-Rashid then went south to capture Marrakesh in 1669, killing the Shabana Arabs in the process. He continued into the Sous region, conquering it by 1670. This reunited Morocco. Al-Rashid is known for building the shrine and mosque of Qadi Iyad in Marrakesh, where his father's remains were moved. Two later Alawi rulers were also buried here.

When al-Rashid died in April 1672, Marrakesh refused to accept his brother and successor, Ismail Ibn Sharif. Instead, the people of Marrakesh chose his nephew. Ismail quickly marched south, defeated his nephew, and entered Marrakesh in June 1672. But his nephew escaped and fled. He returned in 1674, took Marrakesh back, and fortified himself there. Ismail had to lay a two-year siege on the city. Marrakesh finally fell in June 1677, and Ismail took revenge on the city, allowing it to be plundered.

Ismail's punishment of Marrakesh continued. He established his capital at Meknes and built his royal palaces there using materials taken from the palaces and buildings of Marrakesh. Much of the Kasbah, which the Saadians had carefully built, was stripped bare and left in ruins. Most other Saadian palaces in the city were also destroyed. Al-Mansur's great al-Badi palace was almost completely taken apart and moved to Meknes.

However, Ismail also contributed to Marrakesh. He moved the tombs of many Sufi saints to Marrakesh and built new shrines for them. He wanted to create a great pilgrimage festival like those in Essaouira. So, Ismail asked a Sufi leader to choose seven saints to be the "Seven Saints" (Sab'atu Rijal) of Marrakesh. He then organized a new pilgrimage festival. For one week in late March, pilgrims visit all seven shrines in a specific order.

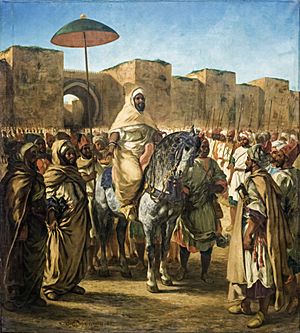

In 1699–1700, Ismail divided Morocco into areas to be ruled by his many sons. But this didn't work well, as several sons used their areas to rebel. One son seized Marrakesh, which had to be retaken. After this, Ismail ended the experiment and took back all the lordships. Chaos returned after Moulay Ismail's death in 1727. A series of Alawi sultans followed, with many coups and counter-coups by rival army groups for the next few decades. Marrakesh did not play a major role in these palace affairs. Abdallah ibn Ismail seized Marrakesh in 1750, placing it under his son Muhammad as viceroy. Muhammad ruled it with great stability while the north was in chaos.

When he became sultan, Muhammad III ibn Abdallah kept Marrakesh as his main residence and capital. The city, especially the Kasbah, had been neglected since Ismail's destruction. Muhammad found much of it in ruins and reportedly had to live in his tent when he arrived. But he soon began rebuilding. He rebuilt the Kasbah almost from scratch, constructing the royal palace Dar al-Makhzen (Palais Royal) and the Dar al-Baida ("White Palace") on the ruins of old Saadian palaces. Muhammad also expanded the walls of Marrakesh to the north to include the mosque and shrine of the patron saint Sidi Bel Abbas al-Sabti, making it a new city district. Much of modern Marrakesh's old city (medina) is due to Muhammad III's rebuilding in the late 1700s.

A crisis followed Muhammad III's death in 1790. His son Yazid was known for his cruelty, and the people of Marrakesh instead chose his brother Hisham. Yazid marched on and recaptured Marrakesh, plundering it violently. But he was killed by Hisham's counterattack. Fez refused to recognize Hisham and chose another brother, Suleiman. Marrakesh itself was divided, with some supporting Hisham and others supporting another brother, Hussein. Suleiman waited while Hisham and Hussein fought each other. Marrakesh finally came under Suleiman's control in 1795.

The plague hit Marrakesh again in 1799, greatly reducing the city's population. Still, Suleiman kept it as his main residence and capital. He completely rebuilt the Ben Youssef Mosque, leaving no trace of its old design. Suleiman was defeated just outside Marrakesh in 1819 during an uprising, but he was saved. After Suleiman's death in 1822, his successor Muley Abd al-Rahman reopened trade with other countries. Marrakesh hosted many foreign visitors seeking trade agreements with the new Alawi sultan. Abd al-Rahman is mainly responsible for replanting trees in the gardens outside Marrakesh.

The 1800s saw growing instability and European powers slowly taking more control in Morocco. The French began conquering Algeria in 1830. Moroccan troops tried to defend Tlemcen, but the French captured it in 1832. Abd al-Rahman supported the resistance in Algeria. The French attacked Morocco directly in 1844, forcing a humiliating defeat on Abd al-Rahman. By this time, Morocco was already unstable, with army units in the north and east difficult to control. Famine also hit Morocco again. Abd al-Rahman's successor, Mohammed IV of Morocco, immediately faced the Spanish War of 1859-60 and another humiliating treaty. While the sultan was busy with the Spanish, a tribe in the south rebelled and besieged Marrakesh. Muhammad IV broke the siege in 1862.

Muhammad IV and his successors Hassan I and Abd al-Aziz moved the court and capital back to Fez. Marrakesh was again a regional capital under a family member. Still, the city was visited often, and many new buildings were constructed. These included the late 19th-century palaces of important officials, such as the Bahia Palace and the Dar Si Said.

As European influence grew in Fez, Marrakesh became a center of opposition to Westernization. Until 1867, individual Europeans were not allowed to enter the city without special permission from the sultan.

The growing European presence changed the relationship between the sultan's government and the rural tribes. To collect more taxes and troops, the Alawi sultan began directly appointing lords (qaids) over the tribes. This process sped up in the 1870s. These appointed qaids became very powerful. In the late 1800s, Madani al-Glawi ("El Glaoui"), a qaid from Telouet, used a cannon given to him by the sultan to control neighboring tribes in the High Atlas. He soon became dominant in the lowlands around Marrakesh.

French Protectorate in Marrakesh

After the death of the grand vizier Ba Ahmed in 1900, the young Alawi sultan Abd al-Aziz tried to rule himself. But he was too influenced by European advisors and soon angered the people. The country fell into chaos, with tribal revolts and plots by powerful lords, along with European meddling. Unrest grew with a terrible famine from 1905–1907 and humiliating agreements in 1906. The Marrakesh khalifa Abd al-Hafid was urged by the powerful southern qaids to lead a revolt against his brother Abd al-Aziz. French troops occupied Oujda in March 1907, and in August 1907, they bombarded and occupied Casablanca. This French action pushed the revolt forward, and the people of Marrakesh declared Abd al-Hafid the new sultan on August 16, 1907. Abd al-Aziz sought French help, which only sealed his fate. Religious scholars in Fez and other cities declared Abd al-Aziz unfit to rule and removed him by January 1908. Abd al-Hafid personally went to Fez to be recognized. Abd al-Aziz finally reacted, gathering his army and marching on Marrakesh in the summer of 1908. But many of his soldiers deserted, and Abd al-Aziz was easily defeated by Abd al-Hafid's forces outside Marrakesh on August 19, 1908. Abd al-Aziz fled and gave up his throne two days later.

In return for their help, Sultan Abd al-Hafid appointed Madani al-Glawi as his grand vizier, and his brother Thami El Glaoui as the pasha (governor) of Marrakesh. Abd al-Hafid's position was difficult due to French military and financial control. Germany and Ottoman Turkey offered support to Abd al-Hafid to counter the French, but French pressure made him even more dependent. The Germans then focused on southern Morocco, making informal agreements with local lords.

Facing financial difficulties and foreign debt, Abd al-Hafid and El Glaoui imposed new heavy taxes, which angered the country. In exchange for a new French loan, Abd al-Hafid had to agree to the Franco-Moroccan accords in March 1911. These agreements gave more tax and property rights to French people living in Morocco and paid France for its military expenses. This caused widespread anger in Morocco. An uprising in Fez had to be put down with French troops, and Abd al-Hafid was forced to dismiss the El Glaoui brothers in June 1911. The entry of French troops worried other European powers. Spanish troops expanded their territory in the north, while Germany sent a warship to Agadir (see Agadir Crisis). During this crisis, the dismissed El Glaoui brothers offered German diplomats to separate southern Morocco, with Marrakesh as its capital, and make it a German protectorate. But this offer was refused as France and Germany were about to sign an agreement resolving the Agadir crisis.

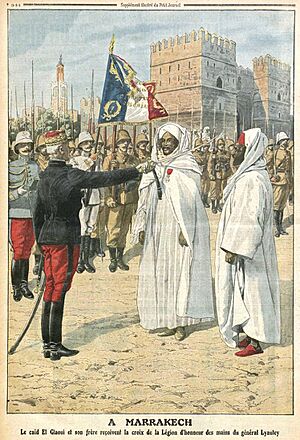

The resolution of the Agadir crisis led to the Treaty of Fez on March 30, 1912. This treaty established a French Protectorate over Morocco. General Hubert Lyautey was appointed the first French Resident-General. The news was met with anger. The Moroccan army rebelled in mid-April, and a violent uprising erupted in Fez. A new column of French troops occupied Fez in May, but rebels were already active. The sultan Abd al-Hafid contacted the rebels, which led General Lyautey to force him to step down on August 11. His brother, Yusuf, became the new sultan and was escorted to the safety of Rabat under French guard.

Discontent in the south grew around Ahmed al-Hiba, known as the "Blue Sultan." He was the son of a late religious leader, and his forces were still in Tiznit. Al-Hiba claimed the Alawites had failed and proposed to cross the Atlas mountains to establish a new southern state based in Marrakesh. From there, he planned to drive the French out of the north. Some southern lords, who had previously been supported by Germany and disliked the idea of French-northern dominance, supported al-Hiba. With their help, al-Hiba quickly took control of the Sous valley. Al-Hiba gathered his tribesmen and began his march over the High Atlas in July 1912. In August 1912, hearing of Abd al-Hafid's abdication, al-Hiba declared the throne empty and was proclaimed the new sultan of Morocco near Marrakesh. The pasha of Marrakesh handed the city over to al-Hiba on August 15.

The rise of a new sultan in Marrakesh worried Lyautey. He decided to send French colonial soldiers to take Marrakesh. Colonel Charles Mangin led this column. Mangin's column met al-Hiba's army at the Battle of Sidi Bou Othman (September 6, 1912). Modern French artillery and machine guns easily defeated al-Hiba's poorly equipped army. Most of the powerful lords switched sides and abandoned al-Hiba. As Mangin approached the city, on September 7, the local leaders, led by El Glaoui, attacked the Hibist forces inside the city. They seized the hostages and drove al-Hiba and his remaining supporters out of Marrakesh. After restoring order, the leaders allowed the French column to enter and take control of Marrakesh on September 9, 1912. Thami El Glaoui was immediately restored as pasha of Marrakesh and received an award from Lyautey.

The region around Marrakesh became a military district. Lyautey relied on the powerful local lords, like El Glaoui, to control the south. El Glaoui proved his loyalty by invading the Sous and driving the Hibists out of Taroudannt. When Madani al-Glawi died in 1918, Lyautey promoted Thami to lead the Glawi clan, making him the undisputed "Lord of the Atlas."

Since the French authorities considered Marrakesh and Fez prone to revolt, the Moroccan capital was permanently moved to Rabat. Marrakesh remained under the firm control of Thami El Glaoui, who served as pasha of Marrakesh for almost the entire French Protectorate period (1912-1956). El Glaoui worked closely with the French and used his power to gain vast properties in the city and region, accumulating a huge personal fortune. His corruption was tolerated by the French, as it ensured his loyalty.

In 1912, Marrakesh had 75,000 inhabitants, living in the Medina, the Kasbah, and the Mellah. City life centered around the Jemaa el-Fnaa. European colonists soon began arriving. By March 1913, about 350 Europeans lived in the city. El Glaoui helped them acquire land. However, not all European visitors were impressed. Edith Wharton, who visited in 1917, found the city "dark, fierce and fanatical."

Lyautey had big plans for urban development, but he also wanted to preserve the historic centers of Moroccan cities. The French urban planner Henri Prost arrived in 1914. He was instructed to plan a new modern city on the outskirts of Marrakesh, mainly for French colonists. Using the Koutoubia mosque and the Jemaa el-Fnaa as central points, Prost directed the development of the new city (ville nouvelle) in what is now Gueliz, northwest of Marrakesh. The church of St. Anne, the first Christian church in Marrakesh, was one of the first buildings in Gueliz. Prost designed a large road from Gueliz to Koutoubia, which is now Avenue Muhammad V. The new city was developed in the 1920s. The Majorelle Garden in Gueliz was created by Jacques Majorelle in the late 1920s.

In 1928, south of Gueliz, Henri Prost began planning the more exclusive quarter of l'Hivernage. This area was meant for French diplomats and officials who spent winters in Marrakesh. It was separated from Gueliz by gardens and sports fields. Hivernage was laid out in the palm and olive groves along the road that connected the old city with the Menara Garden in the west. The avenue was designed to run parallel to the High Atlas mountains, offering great views. With the help of architect Antoine Marchisio, Prost built the luxurious La Mamounia hotel in 1929. This hotel blended Art Deco and Orientalist-Marrakeshi designs. Winston Churchill, who first visited Marrakesh in 1935 and stayed at La Mamounia, considered it one of the best hotels in the world. A casino was soon added. Hivernage became a winter destination for many French celebrities and later for American and European movie stars. The old Atlas qaid, Thami El Glaoui, welcomed these famous guests, hosting lavish parties in his palaces.

Marrakesh, which had been the starting point for many revolts in the past, remained unusually quiet under El Glaoui's control. It was the north that was restless. The Rif War that started in 1919 in Spanish Morocco soon spread into the French Protectorate, threatening Fez. Lyautey resigned in 1925 and was replaced by other residents-general.

Sultan Youssef died in 1927, and his son Mohammed V of Morocco succeeded him. Thami El Glaoui played a key role in this choice and maintained his absolute control over Marrakesh. Young and without much power, Muhammad V initially offered little resistance to the French authorities. He signed the controversial 1930 Dahir, which separated Berbers from Arabs and placed Berbers under French courts. This led to strong anti-French nationalist feelings and the creation of the Hizb el-Watani (National Party) by young nationalist leaders. After riots in Meknes in 1937, French authorities cracked down on the nationalist movements and exiled their leaders. During this time, the French military finally subdued remaining resistance in the remote areas of Morocco.

During World War II, after the fall of France in 1940, the French Protectorate of Morocco came under the control of the Vichy regime. Sultan Muhammad V did not like his new masters. Although generally powerless, the sultan refused Vichy demands when he could. He reportedly rejected Vichy demands in 1941 to pass anti-Jewish laws, saying they were against Moroccan law. Muhammad V welcomed the November 1942 Allied landings in Morocco. He refused Vichy instructions to move his court inland. Muhammad V hosted Allied leaders Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943. During this conference, Churchill took Roosevelt on a side trip to Marrakesh. The Allied presence in Morocco encouraged the nationalist movements, who formed a new party, Hizb al-Istiqlāl (Independence Party) in 1943. However, the French authorities used an Istiqlal petition for post-war independence to crack down on the party in 1944. The French arrested its leaders on false charges of helping the German war effort, causing demonstrations in various cities that were violently suppressed.

In 1946, the new resident-general changed course. He released political prisoners and sought an agreement with the nationalist parties. In 1947, Muhammad V traveled to Spanish-controlled Tangier, where he gave a famous speech that did not mention the French. This was widely seen as expressing his desire for independence and aligning with Istiqlal. This angered the pasha of Marrakesh, Thami El Glaoui, who declared Muhammad V unfit to rule. Working with the French general, Thami El Glaoui arranged for Muhammad V to be removed and exiled on August 13, 1953. He was replaced by his uncle. Nationalists fled to the Spanish zone, and a guerrilla war began soon after, encouraged by the Algerian War next door. Eventually, El Glaoui changed his mind, and in October 1954, he said that Muhammad V should be brought back.

Despite strong opposition from French colonists in Morocco, the French government, facing problems elsewhere, finally agreed to the accords of La Celle-Saint-Cloud in November 1955. The restored Muhammad V returned to Morocco that same month, where he was received with great joy. On March 2, 1956, France officially ended the 1912 treaty of Fez, and Morocco gained its independence. Thami El Glaoui, who had been a symbol of French colonial rule, had died only a few months earlier, ending his powerful rule over Marrakesh.

Marrakesh in Modern Times

After El Glaoui's death in 1956, his huge family properties in and around Marrakesh were taken by the Moroccan state. The city's growth continued mainly to the west. The modern downtown area has been built along Avenue Muhammad V, connecting the Medina with Gueliz. This area has the town hall, banks, and major commercial buildings. Hivernage has seen more hotels and apartment complexes, with luxury villas moving to the Palmerie east of the city. The Dar al-Makhzen (Royal Palace) in the Kasbah, greatly renovated by King Hassan II of Morocco, continues to be a secondary royal residence. The Mellah, which once had a large Jewish population, has become less distinct from the rest of the Medina. Many Moroccan Jews emigrated to Israel after 1948 or to other booming areas like Casablanca.

Since independence, it's often said that while Rabat is the political capital and Casablanca the economic capital, Fez is the intellectual capital, and Marrakesh remains the cultural and tourist capital of Morocco.

Marrakesh has continued to be a popular tourist destination. It started as a luxury winter spot for wealthy Westerners but soon attracted a wider range of visitors. In the 1960s, the city became a trendy "hippie mecca," drawing many Western rock stars, musicians, artists, film directors, actors, models, and fashion icons. Tourism revenues in Morocco doubled between 1965 and 1970. Old buildings in the Old Medina were renovated, new homes and villages were built in the suburbs, and new hotels began to appear.

United Nations agencies became active in Marrakesh from the 1970s, and its international political presence has grown. In 1982, UNESCO declared the old town area of Marrakesh a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This raised international awareness of the city's cultural heritage. In 1994, the Marrakech Agreement was signed here, which established the World Trade Organization. In March 1997, the World Water Council held its First World Water Forum in Marrakesh. In the 21st century, property and real estate development in the city has boomed. There has been a dramatic increase in new hotels and shopping centers. This growth is fueled by the policies of the Moroccan King Mohammed VI of Morocco, who aims to increase the number of tourists visiting Morocco to 20 million a year by 2020.

On April 28, 2011, a bomb attack took place in the Djemaa el-Fna square of the old city, killing 15 people, mostly foreigners. The blast destroyed the nearby Argana Cafe.

From November 7 to 18, 2016, Marrakesh hosted the meeting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), known as COP 22. This conference also served as the first meeting of the governing body of the Paris Agreement. The UNFCCC secretariat was established in 1992 when countries adopted the UNFCCC. In recent years, the secretariat also supports the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action. This partnership was agreed by governments to show that successful climate action needs strong support from many groups, including regions, cities, businesses, investors, and all parts of society. Construction work for the conference site began six months before the event. The site had two zones: the "Blue Zone" for the United Nations, and the "Green Zone" for non-state groups, NGOs, private companies, and local authorities.

See also

- Landmarks of Marrakesh

- Timeline of Marrakesh

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |