History of Poles in the United States facts for kids

The history of Poles in the United States goes back a long way, over 400 years! The first Polish people arrived in America in 1608, even before the Pilgrims. Today, about 10 million Americans have Polish roots. This makes Polish Americans the largest group of people from Slavic countries in the U.S.

Historians often talk about three main periods, or "waves," when Poles came to America. The biggest wave was from 1870 to 1914. A second wave happened after World War II, and a third, smaller one, came after Poland changed its government in 1989. Before these big waves, a few Poles came steadily to the early American colonies. These were often people seeking religious freedom, skilled workers, or adventurous nobles.

Most Polish Americans today are descendants of the first big wave. Millions of Poles left parts of Poland that were controlled by Germany, Russia, and Austria. This journey was often called za chlebem (which means for bread). Many of these migrants were poor farmers who had little land and struggled to find enough food. A large number came from a very poor region in Europe called Galicia. About one-third of these Poles eventually went back to Poland, but most decided to stay.

People from all three waves came to the U.S. because of good job opportunities and higher wages. They often found work in mining, meatpacking, construction, and steel factories. In fact, Poles were a major part of these industries until the mid-1900s. Over 90% of Polish immigrants settled in communities with other Poles. These communities are called Polonia, and the biggest one was in Chicago, Illinois.

Religion was very important to Poles in their homeland. In the U.S., Catholicism became a key part of their Polish identity. Polish immigrants built communities around Catholic churches and schools. They built hundreds of churches and parish schools in the 20th century.

Today, Polish Americans are well-integrated into American society. Their incomes have grown, and many now work in professional and management jobs. However, many Poles still work in construction and industrial jobs. They live all over the U.S., often marry people from other backgrounds, and fewer than 5% can speak Polish fluently.

Contents

- Early Polish Settlers in America

- Poles in the 18th Century

- Polish Life in the 19th Century

- The Big Wave of Polish Immigration (1870–1914)

- Polish Americans in the 20th Century

- World War II and Polish Americans

- Postwar Polish Immigration and Life

- Poles in American Media

- Polish Americans Today

- Images for kids

Early Polish Settlers in America

Poles in the Virginia Colony

The first Polish immigrants arrived in the Jamestown colony in 1608. This was 12 years before the Pilgrims landed in Massachusetts. These early settlers were skilled workers. They were brought by Captain John Smith, an English soldier. These Poles included a glass blower, a tar maker, a soap maker, and a timberman. Historians say these Poles were experts in making tar and pitch, which were important for ships.

In 1619, the Polish colonists went on strike. They were protesting because they were not allowed to vote by the colony's first government. This strike was the first labor protest in the New World. The date of their arrival, October 1, 1608, is now a special holiday for Polish Americans. Polish American Heritage Month is celebrated in October.

Poles Seeking Religious Freedom

Some Protestant Poles left Poland for America to find more religious freedom. After a big war called the Swedish Deluge, a group called the Polish Brethren were told to convert to Catholicism or leave Poland. They faced problems like physical fights and fines for practicing their religion.

These Polish exiles first went to England, but then sought peace in America. Most arrived in New Sweden, but some went to New Amsterdam and the English Virginia colony. These early Poles were generally well-educated and from noble families. One known immigrant, Anthony Sadowski, came from an area with other Protestant groups. Another, Albrycht Zaborowski (Zabriskie), was a Polish Lutheran nobleman who arrived in 1662. His grandson, Peter Zabriskie, became a friend and officer of George Washington.

Poles in the 18th Century

Fighting for American Independence

Later Polish immigrants included Jakub Sadowski, who settled in New York in 1770. His sons were among the first Europeans to explore as far as Kentucky. The city of Sandusky, Ohio, is said to be named after him.

At this time, Poland was losing its independence due to attacks from other countries. Many Polish patriots, like Casimir Pulaski and Tadeusz Kościuszko, came to America to fight in the American Revolutionary War.

Pulaski had led a losing side in a civil war in Poland. He escaped a death sentence by coming to America. He became a Brigadier-general in the Continental Army and led its cavalry. He helped save General George Washington's army at the Battle of Brandywine. Pulaski died leading a cavalry charge at the Siege of Savannah when he was only 31. He is now known as the "father of American cavalry."

Kościuszko was a professional military officer. He served in the Continental Army starting in 1776. He was very important in the American victories at the Battle of Saratoga and West Point. After the American Revolution, he returned to Poland. There, he led an uprising against Russia, but it failed. Both Pulaski and Kościuszko have statues in Washington, D.C.

Another notable Polish American from this time was Peter Zabriskie. He was a patriot and a colonel in the Revolutionary Army. He opened his home to General Washington during a retreat from New York. Peter Zabriskie later became a judge and helped ratify the U.S. Constitution for Bergen County, New Jersey.

After the Revolution, Americans generally thought well of Polish people. Polish music was popular in the U.S. However, after the American Civil War (1861–65), opinions changed. Poles were sometimes seen as rough and uneducated.

Polish Life in the 19th Century

Early Polish Communities

Panna Maria, Texas

The first Polish immigrants from Poland itself came from Silesia, a region then controlled by Prussia. They settled in Texas in 1854. They created a farming community that kept their traditions, customs, and language. They built their homes, churches, and other buildings as a private community in an empty countryside. The first Polish home, the John Gawlik House, was built in 1858. It still stands and has a high-pitched roof, common in Eastern Europe.

Leopold Moczygemba, a Polish priest, founded Panna Maria. He wrote letters to Poland, encouraging people to move to Texas. He described it as a place with free land and fertile soil. About 200-300 Poles made the journey. They were surprised by the desolate fields and rattlesnakes of Texas. Moczygemba and his brothers helped lead the town's development. The settlers and their children spoke Silesian.

Hunting and fishing were popular activities. Farmers used hard work to grow corn and cotton. They sold extra cotton to nearby towns, creating successful businesses. After the Civil War, the Poles in Panna Maria faced discrimination. They had supported the Union. In 1867, a dangerous situation arose with armed cowboys. Polish priests asked the Union Army for protection, and soldiers helped keep them safe. The unique Texas Silesian language still exists today.

Parisville, Michigan

Poles also settled a farming community in Parisville, Michigan, in 1857. Some historians believe it started even earlier, in 1848. Five or six Polish families began this community. They came from Poland by ship in the 1850s and lived in Detroit before starting their farms in Parisville. They turned dark swamps into successful fruit orchards.

The Parisville community was surrounded by Native American Indians. The Poles and Indians had good relationships, sharing gifts and resources. By 1903, about 50,000 Poles lived in Detroit.

Kashubian Settlements in Wisconsin

The oldest Kashubian settlement in the U.S. is in Portage County, Wisconsin. The first Kashubian, Michael Koziczkowski, arrived in Stevens Point in late 1857. One of the first settlements was named Polonia, Wisconsin. Within five years, over two dozen Kashubian families joined the Koziczkowskis. This community was mostly agricultural, spread out over several townships. After the Civil War, more immigrants from different parts of occupied Poland settled there.

Winona, Minnesota and Pine Creek, Wisconsin

The first Kashubian immigrants to Winona arrived in 1859. Starting in 1862, some Winona Kashubians began settling in Pine Creek, Wisconsin. These two places remain connected as one community. Winona became known as the "Kashubian Capital of America" because of how quickly its Kashubian residents became socially, economically, and politically strong. A Polish Museum of Winona was opened in 1977.

Poles in the American Civil War

Polish Americans fought on both sides of the American Civil War. Most were Union soldiers, partly because of where they lived and their support for ending slavery. About 5,000 Polish Americans served the Union, and 1,000 fought for the Confederacy.

Two Polish immigrants became leaders in the Union Army: Colonels Joseph Kargé and Włodzimierz Krzyżanowski. Krzyżanowski first led the 58th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, known as the Polish Legion. This group included Poles and other immigrants. Krzyżanowski later commanded an infantry brigade.

In 1863–1864, Russia stopped a big uprising in Poland. Many Polish fighters fled their country. Confederate agents tried to get them to immigrate and join the Confederate army, but they failed.

After the Civil War

After the Confederacy fell, Southern farms wanted Polish workers to replace formerly enslaved Black people. Several groups in Texas tried to bring in Polish labor. In 1871, Texas even funded European immigration. One group sent a Polish Jew, Meyer Levy, to Poland to recruit about 150 Poles to pick cotton. They arrived in New Waverly, Texas, in May 1867.

The agreement was that farmers would be paid $90 to $110 per year for three years. Owners also provided a "comfortable cabin" and food. Poles paid back their ship tickets in installments. By 1900, Poles had bought almost all the farmland in New Waverly. This town became a "mother colony" for future Polish immigrants. Polish farmers often worked with Black people in east Texas. They sometimes learned words from each other's languages.

Polish immigrants also came in large numbers to Baltimore, Maryland, after the Civil War. They created a community in Fells Point. Many became migrant farming families. Oyster companies from the Gulf of Mexico hired recruiters to find Polish farmers for the oyster industry. Jobs were advertised with pictures of green, tropical places. In 1909, men were promised 15 cents per hour, and women 12.5 cents per hour.

Polish farmers from Baltimore and the southern U.S. often went to Louisiana and Mississippi in the winter. They were given small, crowded living spaces. Only one worker per family usually got a permanent job canning oysters. This work was very hard. Polish foremen were used to manage the workers. Many immigrants did not speak English and relied on their foremen to talk to the company.

The Big Wave of Polish Immigration (1870–1914)

Why Poles Came to America

The largest wave of Polish immigration happened after the American Civil War and before World War I. Many Poles started coming from Prussia in 1870. Prussia had reacted to Polish support for France by increasing Germanization after the Franco-Prussian War. These immigrants were often called za chlebem (for bread) immigrants. They were mostly poor farmers facing hunger in occupied Poland.

A U.S. study in 1911 found that almost all Polish immigrants said they were joining relatives or friends. This shows that letters sent home played a big role in encouraging immigration. They came first from German-controlled Poland, then from Russian and Austrian parts. U.S. laws in the 1920s and the chaos of World War I greatly reduced immigration. About 1.5 million Poles came during this big wave.

During the time Poland was divided by other countries (1795–1918), the Polish people had to define themselves as a group without their own country. However, the Polish communities in the U.S. were built on a shared national culture. They became like a "fourth province" for Poland.

Life in Poland Before Emigration

Poland was mostly a farming society for a long time. Polish farmers were usually peasants. They were controlled by Polish nobles who owned the land and limited their freedoms. Peasants were not allowed to trade freely. They had to sell their animals to the nobles, who then acted as middlemen.

In the mid-1800s, new farming methods were brought to Poland from Britain. These methods, like a four-crop rotation system, tripled the amount of food grown. This created a surplus of farm workers. Before this, Polish peasants used a three-field rotation, which meant one year of rest for the soil. Instead of leaving a field empty, new crops like turnips and red clover helped the soil and fed cattle.

Between 1870 and 1914, over 3.6 million people left Polish lands. About 2.6 million of them came to the U.S. Serfdom, a system where peasants were tied to the land, was abolished in different parts of Poland between 1808 and 1861. As industries grew and the population boomed, many Polish farmers became migrant workers. They faced discrimination and unemployment, which pushed them to emigrate.

Poles Under German Rule

The first Poles to emigrate came from German-controlled Poland. German areas had advanced farming technology by 1849, leading to a surplus of farm workers. This also caused the Polish population to grow, as fewer babies died and less people starved.

In 1886, Otto von Bismarck spoke about his anti-Polish policies. He worried about over a million Poles in Silesia who could fight Germany. Bismarck forced 30,000–40,000 Poles out of German territory in 1885. Many Poles went to the U.S. during this time. Bismarck's anti-Catholic policies also caused more Poles to leave. About 152,000 Poles left for the U.S. during this period.

Poles Under Russian Rule

The Russian part of Poland saw a lot of industrial growth, especially in the textile city of Łódź. Russia actually encouraged foreign immigration. Polish workers were wanted in iron factories and Siberian towns. Russia also created a bank to help peasants own land. This moved many Poles from farms to industrial cities. The number of industrial workers grew from 80,000 to 150,000 between 1864 and 1890.

Poles under Russian rule faced increasing pressure to become more Russian. From 1864, all education had to be in Russian. Polish newspapers and plays were allowed but often censored. Young men who failed Russian exams were forced into the Russian Army. After Russia's economy declined, more Poles emigrated. Polish leaders at first discouraged emigration. But when Poles in the U.S. sent money back home, attitudes changed.

One famous immigrant from this time was Marcella Sembrich, an opera singer. She moved to the U.S. and spoke about the discrimination she faced in Poland. She was not allowed to sing in Polish in public.

Poles Under Austrian Rule

Polish children in Austrian Galicia often did not get much education. By 1900, over half of all men and women over six years old could not read or write. Austrian Poles started immigrating to the U.S. around 1880. The Austrian government tried to stop emigration because many young Polish men wanted to avoid military service. Peasants were also unhappy with their hard farm work and lack of opportunities.

Galician Poles faced some of the hardest conditions. They were isolated and used old farming methods. They suffered from diseases like typhus and cholera, and a potato famine, but help did not reach them. Their difficult situation was called the "Galician misery."

Many Austrian Poles became very religious in the late 1800s. The number of Polish nuns increased six times in Galicia. Young women often chose to become nuns to avoid hard farm work.

Jobs for Polish Immigrants

American employers really wanted Polish immigrants for low-level jobs. In steel mills, foremen often chose Poles because they were known to be very hardworking. Steel work was tough, with 12-hour days, 7 days a week. Polish immigrants often helped their friends and relatives get jobs. They liked steel areas and mining camps, especially in cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh. Few went to New England or farming areas, and almost none went to the South. By 1920, a large number of U.S. coal miners and blast furnace workers were Polish.

Working in Blast Furnaces

Many Poles took low-paying jobs at blast furnaces. The demand for these jobs changed, hours were long, and there were many workers available. An industrialist named Amasa Stone actively recruited Poles for his steel mill in Ohio in the 1870s. He promised jobs at $7.25 a week and a free ship ride to the U.S. Hundreds of Poles took these jobs, and Cleveland's Polish population grew quickly.

In 1910, most workers had 84-hour work weeks (7 days, 12 hours a day). Day and night shifts rotated every two weeks, meaning men sometimes worked 18 or 24 hours straight. Some workers did not mind the long hours, seeing it as necessary. When the 7-day week was ended, some workers quit because they felt their time off was wasted.

Mining for Coal

West Virginia saw many immigrant coal miners in the early 1900s. By 1930, almost 15,000 Poles lived there. Poles were the third-largest immigrant group in West Virginia's mining industry. They also came to Colorado for coal mining.

Poles often worked with other Slavic immigrants. Work safety signs in mines were often in Polish, Lithuanian, Czech, and Hungarian. Pennsylvania attracted the most Polish miners. Employment in mining grew from 35,000 in 1870 to over 180,000 in 1914. Before World War I, over 80% of Poles in northern Pennsylvania worked in coal mines.

In 1903, a Polish-language newspaper called Gornik (Miner) started in Wilkes-Barre. It shared local industry news. In 1897, a Pennsylvania committee found miners' salaries were very low. They said it was "impossible for any moderate sized family to more than exist."

Polish miners joined unions like the United Mine Workers. They participated in strikes, helping to bridge past differences with other groups. Descendants of Polish miners still live in these industrial areas. A novel called Theodore Roosevelt by Jennifer Armstrong shows the tough conditions faced by Polish American coal mining families in 1901.

Working in Meatpacking

Polish immigrants were a major part of the meatpacking industry in the Midwest from the late 1800s until World War II. The meatpacking industry was huge in Chicago in the 1880s. Many Poles joined Chicago's packing plants in 1886. They came to dominate the profession through their networks and future generations.

Workers, including new Polish arrivals, would gather outside the plants early in the morning. Hundreds or thousands of mostly unskilled laborers waited for an hour. The employment agent would pick the strongest-looking men. There was no bargaining over wages or hours. Job security was rare. Workers were often laid off each year because livestock supplies changed with the seasons.

Child Labor in Factories

In 1895, government inspectors found a child working at a dangerous machine. The child said his father was injured and would lose his job if he didn't work. Illinois labor inspectors needed Polish translators because some child workers in 1896 could not answer simple questions in English. Reports also found that parents faked birth records to get around laws against children under 14 working. Investigations showed that work often started at age 10 or 11.

Because of strong government action against factories, the number of children under 16 working in urban Illinois fell from 8,543 to 4,264 between 1900 and 1914.

Polish Farmers in America

Poles often had years of farming experience before coming to America. They became known as skilled farmers in the U.S. Many Polish immigrants came to the Northern U.S. hoping to work in factories. However, they often ended up in farming because of stereotypes and economic needs.

In New England, Poles used land that American farmers had left empty. Poles had even better crop yields than local Americans. This was because they worked very hard and were willing to try lands thought to be worthless. Poles succeeded quickly. In Northampton in 1905, Poles were 4.9% of the population but owned 5.2% of the farmland. By 1930, they were 7.1% of the town and owned 89.2% of the farmland. Their success was due to their large families, where children helped, and their long work hours.

Lenders saw Polish immigrants as low credit risks. This was because Poles were thrifty, hardworking, and honest. They were said to show "immigrant Puritanism," being more economically careful than the original New Englanders.

Starting Businesses

Few Poles opened shops, restaurants, or other businesses. Poles from Galicia and Russia came to the U.S. with the fewest resources and education. They often did hard labor their whole lives. Even German Poles, who had more advantages, were slow to start businesses. For first- and second-generation Poles who did start businesses, supermarkets and saloons were the most popular.

Historian John J. Bukowczyk said that Poles being happy with steady paychecks hurt their families and future generations. While other immigrant groups were slowly moving up through small businesses, Poles often stayed in less challenging careers.

Early Views of Polish Immigrants

The immigrants of the late 19th and early 20th century were very different from earlier Poles. Most were poor, uneducated, and willing to do manual labor. Some studies in the early 1900s, like by Carl Brigham, wrongly claimed that Poles had lower intelligence. He used English tests from the U.S. military.

A U.S. Congress study also said Poles were not good immigrants because of their "unstable personalities." Future U.S. President Woodrow Wilson called Poles, Hungarians, and Italians "men of the meaner sort" in 1902. He said they lacked "skill nor energy nor any initiative of quick intelligence." Wilson later apologized for these comments.

Polish immigrants had many children in the U.S. A 1911 report noted that Poles had the highest birth rate. By 1910, more children were being born to Polish immigrants than the number of Poles arriving. In some Polish communities, nearly three-fourths of Polish women had at least 5 children. This "baby boom" for Polish Americans lasted from 1906 to 1915.

Coming Through Ellis Island

Most Polish immigrants came through Ellis Island in New York. Ellis Island gained a bad reputation among Poles. A reporter in the 1920s found that Polish immigrants were treated as "third class" and faced humiliation. The Cleveland Polish newspaper Wiadomości Codzienne reported that officers at Ellis Island made women undress in public.

U.S. law banned poor immigrants. A reporter at Castle Garden found that 60 Poles were held because they were "destitute and likely to become public charges." Polish Americans were upset by the Immigration Act of 1924. This law greatly limited Polish immigration to levels from 1890, when there was no independent Polish nation. A Polish American newspaper asked, "If the Americans wish to have more Germans and fewer Slavs, why don't they admit that publicly!?"

Official records of Polish immigrants are not always clear. Estimates generally say over 2 million Polish immigrants came. Some reports say as high as 4 million. During the time Poland was divided, U.S. agents categorized immigrants by their country of origin (Austria, Prussia, or Russia). Immigrants could also state their "race or people." About 1.6 million people reported being of "Polish race" between 1821 and 1924. This is likely an undercount.

Ellis Island officials checked immigrants for weapons and criminal intentions. In 1894, daggers found on some Polish immigrants led to stricter inspections. Officials found that most Poles came with plans to work on farms and in factories, usually in communities with other Poles.

Polish Americans in the 20th Century

Growing a Polish Identity

Polish immigrants to the U.S. were usually poor farmers. They often didn't know much about Polish civic life, politics, or education. Poland had not been independent since 1795. Peasants often didn't trust or care much about the government, which was controlled by nobles.

Some historians believe a Polish national identity grew among Polish Americans during World War I. But it fell sharply afterward. Polish immigrants often knew little about Poland beyond their local villages. During World War I, the Polish government asked for donations, promising good status back in Poland if they returned. After the war, many Polish Americans felt angry that they had delayed improving their own lives for Poland.

Polish Catholic Schools

Polish Americans usually joined local Catholic churches. They were encouraged to send their children to these church schools. Polish-born nuns often taught there. In 1932, about 300,000 Polish Americans were in over 600 Polish grade schools in the U.S. Few went on to high school or college at that time.

Polish Americans strongly supported Catholic schools. In Chicago, 36,000 students (60% of the Polish population) attended Polish church schools in 1920. Almost every Polish church in America had a school. Even in 1960, about 60% of Polish American students went to Catholic schools.

Many Polish American priests in the early 1900s were part of the Resurrectionist Congregation. They sometimes had different ideas from the main American Catholic Church. Polish American priests created their own schools and universities.

Milwaukee was a very important Polish center. By 1902, 58,000 Poles lived there. Most came from Germany and worked in factories. They supported many community groups and newspapers. The first Polish Catholic school opened in 1868. This meant children didn't have to go to public schools or German Catholic schools.

In the 1920s, morning lessons in Polish schools were taught in Polish. They covered the Bible, Catechism, Church history, Polish language, and Polish history. All other subjects were taught in English in the afternoon. By 1940, most teachers, students, and parents preferred English.

The 1920s were the peak for the Polish language in the U.S. A record number of people reported Polish as their native language in the 1920 U.S. Census. Since then, the number has dropped as Poles have become more Americanized. In 2000, about 667,000 Americans over age 5 spoke Polish at home.

Poles and the American Catholic Church

Polish Americans built their own Catholic churches and parishes in the U.S. People would gather, collect money, and choose leaders. When the community grew, they would ask the local bishop for permission to build a church and get a priest. Often, Polish immigrants built their churches first and then asked for a priest.

Roman Catholic churches built in the "Polish cathedral style" are very fancy. They have lots of decorations, columns, and images of the Virgin Mary and Jesus. Devout Poles gave a lot of money to build their churches. Some even mortgaged their homes. In Chicago, poor Poles with large families still gave big parts of their paychecks. People felt very strongly about their churches being finished.

Poles were often upset with the "Americanization" and especially "Irishization" of the Catholic Church in America. In Poland, churches were usually funded by nobles and taxes. But in the U.S., churches relied on immigrants, mostly from peasant backgrounds. Polish churches in the U.S. were often funded by Polish groups like the Polish National Alliance (PNA) and the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America (PRCNU). These groups provided financial help to members and gave money to churches.

Church leaders often wanted to keep their power over church decisions. But parishioners, who had elected church committee members and paid for expenses, were used to having a say. This led to struggles with clergy who expected more authority. For example, a bishop in Cleveland criticized a Polish American priest for letting people elect church committee members instead of appointing them.

Polish Catholics generally agreed on Catholic beliefs. But they brought Polish customs into American churches. These included Pasterka (midnight mass on Christmas Eve), gorzkie żale (bitter lamentations devotion), and święconka (blessing of Easter eggs).

Founding the Polish National Church

Many Polish Americans were very religious. They wanted Polish services and more Polish priests and bishops. They were frustrated by the lack of Polish representation in church leadership. Many felt it was unfair that they couldn't help make decisions or manage church money. Polish people had donated millions to build churches, but these churches were legally owned by German and Irish clergy.

A big conflict happened in Scranton, Pennsylvania. A large Polish population had settled there for coal mining and factory jobs. They saved money to build a new Roman Catholic church. But they were offended when the church sent an Irish bishop to lead services. Polish people repeatedly asked to be involved in church matters, but were refused. The bishop called them "disobedient."

People had fights outside the church, and some were arrested. A Catholic priest named Francis Hodur heard these stories. He told the unhappy parishioners to organize and build a new church that the people themselves would own. They followed his advice. But when they asked the bishop to bless the building, he refused. He demanded that the property title be in his name.

Hodur disagreed and started leading church services on March 14, 1897. He was excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church in 1898 for not giving up ownership of the church property.

Francis Hodur's Polish church grew as Polish families left the Roman Catholic Church. The Polish National Catholic Church (PNCC) expanded. It also welcomed other groups. Lithuanians and Slovaks formed their own churches and later joined the PNCC. The PNCC believes in the property rights and self-determination of regular church members. In the PNCC's St. Stanislaus church, there is a stained glass window of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln's birthday is a church holiday because he defended Irish Catholics who refused to give their church property to the Catholic church. The PNCC grew across the U.S., mainly in Chicago and the Northeast.

Being an Outsider: Low Social Status

Polish immigrants were the lowest-paid white ethnic group in the U.S. A study before World War I found that in Brooklyn, New York, Poles earned less than Norwegians, English, and Czechs. Despite common stories of anti-Irish discrimination, Irish immigrants actually earned average or above-average wages. Poles faced more job segregation than the Irish.

However, by the 1960s, Polish Americans had above-average incomes. But few were executives or professionals. Historians suggest that Polish workers chose good-paying union jobs and home ownership over more prestigious careers.

In the early 1900s, anti-Polish feelings gave Polish immigrants a low social status. Other white groups like the Irish and Germans had become Americanized. They gained power in the Catholic Church and government. Poles were far behind. Poles had little political or religious say until 1908. That year, the first American bishop of Polish descent, Paul Peter Rhode, was appointed in Chicago. This happened because Polish Americans pushed for a bishop from their own background.

Poles were seen as strong workers, with good physical health and stubborn character. They were thought to be capable of heavy work from morning till night. Most Polish immigrants were young men in good physical shape. The lack of educated Poles coming to the U.S. made this stereotype stronger. Polish immigrants often saw themselves as common workers. They had a feeling of being outsiders. They just wanted peace and security within their own Polish communities. Many found comfort in the job opportunities and religious freedoms in the U.S.

World War I (1914–18) and Polish Americans

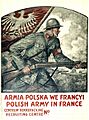

World War I encouraged Polish Americans to help defeat Germany and free their homeland. They strongly supported the war effort. Many volunteered for or were drafted into the U.S. Army. They worked in war industries and bought war bonds. A common goal was to fight for America and for Poland to become a united, independent nation again.

Polish Americans were personally affected by the war. They heard reports of Poles fighting for both sides and Polish newspapers confirmed deaths for many families. Communication with families in Poland was very hard, and immigration stopped. After the war, one estimate said that 220,000 Poles were in the U.S. army. Polish names made up 10% of the casualty lists, even though Poles were only 4% of the country's population. Over 40% of the first 100,000 volunteers for the U.S. Armed Services were Polish American.

In 1917, France decided to create a Polish Army to fight on the Western Front. Canada helped with recruiting and training. This army was called the Blue Army because of its uniform. The U.S. allowed recruiting of men who were not eligible for the draft. This included recent Polish immigrants who hadn't lived in the U.S. long enough to become citizens. It also included Poles born in Germany or Austria, who were considered enemy aliens. The Blue Army grew to nearly 22,000 men from the U.S. and over 45,000 from Europe. It entered battle in summer 1918. After the war, the Blue Army helped establish the new Polish state. Most veterans from the U.S. returned home in the 1920s.

Polish pianist Ignacy Paderewski came to the U.S. and asked immigrants for help. He raised awareness about the suffering in Poland. Paderewski used his fame to sell dolls to benefit Poland. The dolls were dressed in traditional Polish clothes. Sales helped Polish refugees in Paris and provided food for the poor in Poland.

President Wilson named January 1, 1916, as Polish Relief Day. Money given to the Red Cross that day went to help Poland. Polish Americans often gave a day's pay to the cause. They also bought over $67 million in Liberty Loans to help fund the war.

Between the World Wars (1920s and 1930s)

By 1917, there were over 7,000 Polish organizations in the U.S. They had about 800,000 members. The most important were the Polish Roman Catholic Union (founded 1873), the PNA (1880), and the Polish Falcons (1887). Women also created their own groups.

The PNA was formed in 1880 to get support for Poland's freedom. It discouraged Poles from becoming too Americanized before World War I. After 1945, it focused more on social activities and its insurance program.

The first Polish politicians began seeking major offices. In the 1930s, the Polish vote became important in big industrial cities. Poles largely switched to supporting the Democratic Party. Charles Rozmerek, the PNA president from 1939 to 1969, built a political network in Chicago. He played a role in Chicago's Democratic politics.

After World War I, the new Polish state began to recover. Some Poles tried to return home. It's estimated that 30% of Polish emigrants from Russian-controlled lands went back. For non-Jews, the return rate was closer to 50–60%. More than two-thirds of emigrants from Austrian-controlled Galicia also returned.

Anti-Immigrant Feelings in the 1920s

Some Americans had strong anti-immigrant feelings in the 1920s. They opposed the immigration and assimilation of Poles. In 1923, Carl Brigham continued to say Poles were less intelligent. He argued that even though there were famous Poles like Kościuszko and Pulaski, the overall group was not as smart.

Polish communities in the U.S. were targeted by anti-immigrant groups in the 1920s.

Poles and the American Labor Movement

Polish Americans were very active in strikes and trade unions in the early 1900s. Many worked in industrial cities and organized trades. They played a big part in historical labor struggles. Political leaders emerged from the Polish community. Leo Krzycki, a Socialist leader, was known as a powerful speaker. He was hired by unions to educate workers in both English and Polish from the 1910s to the 1930s.

Krzycki helped organize strikes in the Chicago-Gary steel strike of 1919 and the Chicago packing-house workers strike in 1921. He was very good at getting Polish Americans involved. He was also connected to the first 24-hour sit-down strike at Goodyear Tire in 1936. Polish Americans made up 85% of the Detroit Cigar Workers union in 1937, during the longest sit-down strike in U.S. history.

The Great Depression's Impact

The Great Depression in the United States severely hurt Polish American communities. Factories and mines cut jobs. In the Polish neighborhood of Hamtramck, Detroit, there was poor public sanitation, high poverty, and overcrowding. In 1932, nearly 50% of Polish Americans were unemployed. Those who still worked faced bad conditions and low wages.

As jobs became harder to find, more Black people and poor white people from the South moved to Detroit. They competed with Poles for low-paying jobs. Companies sometimes hired Black people to break strikes by mostly Polish-American unions. For example, the Ford Motor Company used Black strikebreakers against the United Auto Workers union, which had many Polish-American members. This led to violent clashes. Tensions grew, leading to the race riot of 1943.

World War II and Polish Americans

Polish Americans strongly supported Roosevelt and the Allies against Nazi Germany. They worked in war factories, grew victory gardens, and bought many war bonds. Out of 5 million Polish Americans, about 900,000 to 1,000,000 (20% of their population) joined the U.S. Armed Services. They were common in all military branches and were among the first to volunteer.

Polish Americans made up 4% of the American population but over 8% of the U.S. military during World War II. Matt Urban was one of the most decorated war heroes. Francis Gabreski became known as the "greatest living ace" for his air combat victories.

During World War II, General Władysław Sikorski tried to recruit Polish Americans for a separate Polish battalion. But many were second and third generation Poles who did not join in large numbers. Only 700 Poles from North America and 900 from South America joined the Polish Army. Historians say Sikorski's approach was difficult because he told Polish Americans he didn't want their money, only young men for the military.

Later in the war, Polish Americans became very interested in the political situation in Poland. Most Polish American leaders believed Polish Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski should negotiate with the Soviet Union. However, some, like Maksymilian Węgrzynek, were strongly anti-Soviet. He founded the National Committee of Americans of Polish Descent (KNAPP) in 1942 to oppose Soviet control in Poland. His newspaper became a voice for exiled Polish leaders who feared the Polish government was falling apart. Most American Poles agreed with the anti-Soviet views.

Three important pro-Soviet Polish Americans were Leo Krzycki, Stanislaw Orlemanski, and Oskar R. Lange. They were disliked by many Polish Americans in New York and Chicago, but had strong support in Detroit. Orlemanski started the Kosciusko League in Detroit in 1943 to promote American-Soviet friendship. Lange had a lot of influence among Detroit Poles. He argued that Poland could return to its "democratic" roots by giving up some land to Belarusians and Ukrainians. He also suggested giving farmland to peasants. These ideas matched later agreements between America and the Soviet Union.

In 1944, a Russian diplomat suggested that Krzycki, Orlemanski, and Lange would be good leaders for Poland. Stalin supported this idea. President Roosevelt agreed to quickly process their passports to visit Russia. Lange visited Russia and met with Stalin. He then returned to the U.S. and urged Polish Americans to accept that Poland would give up some land and that a communist government was coming.

After the War: Polonia's Response

After World War II, American Poles became very interested in Poland again. Polish American newspapers, both anti- and pro-Soviet, supported Poland getting the Oder-Neisse line from Germany. Poland's borders were changing after the war, and Polish Americans worried if the U.S. would ensure they got these western territories.

The Potsdam Agreement said Poland's borders would be "provisional" until an agreement with Germany was signed. After the war, America occupied West Germany, and relations with the Soviet bloc became difficult. Polish Americans feared that close ties between the U.S. and West Germany would mean distancing from Poland.

The Polish American Congress (PAC) was created in 1944. Its goal was to make sure Polish Americans had a political voice to support Poland after World War II. In 1946, the PAC went to Paris to try and stop the U.S. Secretary of State from making more agreements with Germany. Polish Americans were angry when the Secretary said German public opinion should be considered in border claims.

Even pro-Soviet Polish Americans called these lands "Recovered Territories." This showed wide support among American Poles. The PAC remained suspicious of the U.S. government. In 1950, after East Germany and Poland signed an agreement on the Oder-Neisse line, the U.S. still said a final border resolution would need another peace conference.

Postwar Polish Immigration and Life

Second Wave of Immigration (1939–89)

A wave of Polish immigrants came to the U.S. after World War II. Unlike the first wave, they often could not return to Poland. They became Americanized quickly, learned English, and moved into the middle class. They faced less discrimination than the first wave.

This group of immigrants also had a strong Polish identity. Poland had developed a strong national and cultural identity in the 1920s and 1930s when it gained independence. These immigrants brought much of that culture to the U.S. They were more likely to seek professional jobs and express pride in Poland's history.

Many of these immigrants were aristocrats, students, or middle-class citizens. They had been categorized by Soviet police. Polish military officers were killed, and civilians were sent to remote areas or Nazi camps. During and after the war, many Poles escaped Soviet control by fleeing to countries like the United Kingdom, France, and the U.S.

A small, steady flow of immigrants from Poland has continued since 1939. In the 1980s, about 34,000 refugees came, fleeing communism in Poland. Another 29,000 regular immigrants also arrived. Most newcomers were well-educated professionals and artists. They usually did not settle in the old Polish neighborhoods.

Polish Americans Since 1945

In 1945, the Red Army took control, and Poland became a Soviet-controlled country until 1989. Many Polish Americans felt betrayed by Roosevelt's agreements with Stalin. After the war, some higher-status Poles were outraged by Roosevelt's acceptance of Soviet control over Poland. They shifted their votes to conservative Republicans who opposed the Yalta agreement. However, working-class Polish Americans remained loyal to the Democratic Party.

The first Polish American on a national political ticket was Senator Edmund Muskie (Marciszewski). He was nominated by the Democrats for vice president in 1968. He later ran for president and served as Secretary of State. The first Polish American in the President's Cabinet was John A. Gronouski, chosen by John F. Kennedy in 1963.

By 1967, there were nine Polish Americans in Congress. Three well-known Democrats were Clement J. Zablocki, Dan Rostenkowski, and John Dingell. Zablocki served from 1949–83 and chaired the House Foreign Affairs Committee. Rostenkowski served from 1959–95 and chaired the powerful House Ways and Means Committee, which writes tax laws. Dingell served from 1955 to 2015, becoming one of the longest-serving members of Congress. He was a major voice on economic, energy, medical, and environmental issues. His father, John D. Dingell, Sr., also held the same seat in Congress.

One historian identified a rise in Polish immigration in the 1960s and 1970s as the "Third Wave." Poland became more open to emigration, and U.S. immigration policy was kind to Poles. Interviews with these immigrants found they were often surprised by how important money and careers were in the U.S. They also noted that America had less social welfare than Poland.

Polish and Black Relations (1960s and 1970s)

Polish Americans settled in Detroit's east side, in an area called "Poletown." In the 1960s, Detroit's Black population grew, while many white residents left. Polish Americans were among the last white groups to stay. They had invested millions in their churches and schools. They also sent money to family and friends in Poland.

Some Polish Americans in Chicago were against Martin Luther King, Jr.'s efforts for open housing. This meant allowing Black people to live in Polish urban communities. Racial tensions led to violent riots between Polish and Black communities in 1966 and 1967, especially in Detroit.

By 1970, Hamtramck and Warren, Michigan, were still very Polish. These communities became "naturally occurring retirement communities." Young families moved away, leaving elderly residents alone. Many older Polish Americans lost the help of their children and had fewer community members to rely on. This led to increased depression, isolation, and loneliness.

Polish Surnames in America

Polish Americans often changed their names to fit into American society. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, immigration agents at Ellis Island often changed names. For example, Edmund Muskie's Polish surname was Marciszewski. In the 1960s and 1970s, many Poles chose to change their own names to sound more English. In Detroit, over 3,000 Polish Americans changed their names each year in the 1960s.

Americans often did not try to pronounce Polish last names correctly. Poles in public positions were told to change their names. Many Polish American children also quickly changed their first names to American versions (like Mateusz to Matthew).

A 1963 study of 2,513 Polish Americans who changed their last names showed a pattern. Over 62% changed their names completely, with no resemblance to the Polish original (e.g., Czarnecki to Scott). The second most common choice was to remove the Polish-sounding ending (e.g., Ewanowski to Evans). It was very rare for a name to be shortened with a Polish-sounding ending.

Civil Rights for Polish Americans

Polish Americans found that U.S. courts did not always protect their civil rights. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 says no person should face discrimination based on race, color, or national origin. However, in one case, a judge ruled that this law did not protect a Slavic employee who was fired for speaking up about anti-Slavic discrimination. The lawsuit was dismissed because he was not considered part of a "protected class."

In another case, a Polish American trying to sue for equal opportunity employment was told his case was invalid. The court said "only nonwhites have standing to bring an action." Poles were also affected by the destruction of their Poletown East community in Detroit in 1981. Corporations used eminent domain to take their historic town.

Aloysius Mazewski of the Polish American Congress felt that Poles were overlooked by changes to U.S. law. He argued for changes so that "groups as well as individuals" could sue for defamation and civil rights. Senator Barbara Mikulski supported this idea, but no law has been passed to amend this for ethnic groups not recognized as racial minorities.

1980s and Poland's Freedom

U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Pope John Paul II put a lot of pressure on the Soviet Union in the 1980s. This helped lead to Poland's independence. Reagan supported Poland's freedom by protesting against martial law. He asked Americans to light candles for Poland to show support for their repressed freedoms. In 1982, Reagan met with European leaders to push for economic actions against the Soviet Union to help liberalize Poland.

The public image of Polish suffering hurt the Soviets. To improve their image, the Soviets gave amnesty to some Polish prisoners. They also gave a one-time economic boost to Poland. George H. W. Bush met with Solidarity leaders in Poland starting in 1987. On April 17, 1989, Bush announced his economic policy toward Poland in Hamtramck, Michigan. This city was chosen because it had a large Polish American population.

Bush's plan was a modest aid package, but by 1990, the U.S. and its allies gave Poland $1 billion to help its new capitalist market. The U.S. Ambassador in Poland found that Bush's speech was closely watched in Poland. He predicted it could greatly change their government. The Ambassador noted that Poles held the U.S. in very high regard. This was partly because of the economic success of 10 million Polish Americans.

New Wave of Immigration (1989–Present)

Polish immigration to the U.S. saw a small increase after 1989. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of Soviet control allowed more Poles to emigrate. Many who had been waiting left for Germany or America. The United States Immigration Act of 1990 helped immigrants from 34 countries affected by earlier laws. In 1992, over a third of Polish immigrants were approved under this act. The most popular destinations for Poles after 1989 were Chicago and New York City. These immigrants were older, averaging 29.3 years in 1992.

Poles in American Media

American media has often shown Poles in a negative way. Fictional Polish Americans are sometimes shown as rough or unintelligent. They are often the target of jokes. In the TV series Banacek, the main character was described as a "walking lightning rod for Polish jokes." In the 1961 film West Side Story, a character uses a slur against Tony, who is part Polish.

Folklorist Mac E. Barrick noted that TV comedians were hesitant to tell ethnic jokes until 1968. That's when Spiro Agnew made "polack jokes." Barrick said that even though "Polack jokes" were not as bitter as racial humor, they targeted a small minority group. This group was not involved in national controversy and had no strong organization to protest.

In the 1970s, there was a renewed interest in white ethnic identity. The popular 1970s sitcom Barney Miller showed a Polish-American character, Sergeant Wojohowicz, as uneducated and slow. One of the worst shows was All in the Family. The main character, Archie Bunker, often called his son-in-law a "dumb Polack." This made the jokes and the word "Polack" more accepted. Sociologist Barbara Ehrenreich called the show "the longest-running Polish joke."

The term "Polack" was so common in the 1960s and 1970s that even high-ranking U.S. politicians used it. Ronald Reagan told Polish jokes multiple times during his 1980 presidential campaign and presidency. As late as 2008, Senator Arlen Specter told Polish jokes.

The Polish American community has tried to sue to stop negative portrayals of Poles in Hollywood, but often without success. The Polish American Congress asked the Federal Communications Commission to stop ABC from showing the "dumb polack image." A lawsuit against Paramount Pictures in 1983 over "Polish jokes" in the movie Flashdance was dismissed. The judge said "the telling of Polish jokes does not attain that degree of outlandishness" to hurt Poles' jobs or businesses.

Polish Americans Today

Polish Americans are largely integrated into American society. Strong personal connections to Poland and Polish culture are not as common. Of the 10 million Polish Americans, only about 4% are immigrants. Most are American-born.

Among Poles of single ancestry, about 90% live in mixed-ethnic neighborhoods. No U.S. congressional district or large city is mostly Polish, though some Polish communities still exist. About 50% of American-born Poles eat Polish dishes. This is less than Italian Americans, but more than Irish, English, Dutch, or Scottish Americans.

Growth of Polish American Organizations

There has been growth in Polish American organizations in the early 21st century. The Piast Institute was founded in 2003. It is the only Polish "think tank" in America. It is recognized by the U.S. Census Bureau as an official Census Information Center. It provides historical and policy information to Polish Americans. The American Polish Advisory Council helps Poles in politics and public affairs address issues in the community. Both are non-religious groups.

Historically, Polish Americans linked their identity to the Catholic Church. One historian noted that "Secular Polish Americanness has proved ephemeral and unsustainable over the generations." He said the decline of Polish churches led to a decline in Polish American culture and language.

The first The Polish American encyclopedia was published in 2008. In 2009, Pennsylvania approved the first ever Polish American Heritage Month.

Efforts Against Negative Stereotypes

Polish Americans still face discrimination and negative stereotypes in the U.S. In February 2013, a YouTube video about Pączki Day (a Polish donut day) said that on that day, "everybody is Polish, which means they are all fat and stupid." The Polish Consulate contacted the video creator and YouTube, and it was removed.

In December 2013, the Polish American Congress sent a letter to Disney-ABC Television. They asked them to stop late-night host Jimmy Kimmel from making fun of Poles as "stupid." In October 2014, lawyers announced a lawsuit for a mining foreman named Michael Jagodzinski. He sued his former employer for discrimination based on national origin. Jagodzinski faced insults and was called a "dumb Polack." He was fired after complaining to management. In 2016, he received money as part of a settlement.

The United States Geological Survey still lists natural places with the name "Polack." As of 2017, there are six such features and one location.

Images for kids

-

Kościuszko statue, Detroit

-

A field planted with crimson clover to enrich farm soil. The use of clover tripled Polish farm output and increased productivity of cattle in the late 19th century.

-

Photograph of Sembrich, who sang at the Metropolitan Opera. She wore traditional Polish dresses at her concerts.

-

Meatpackers inspecting pork, 1908. Poles were the most numerous ethnic group in Chicago's Union Stockyards during the early 20th century.

-

Polish boy sitting at his workstation in Anthony, Rhode Island, 1909. He was a spinner at a textile mill.

-

Polish-American grocery, 1922, Detroit, Michigan.

-

Erazm Jerzmanowski, a Polish-born industrialist who founded lighting-gas companies in Chicago, Baltimore and Indianapolis. He was the richest Pole in the United States in the 19th Century

-

Polish-Americans who fought in the Blue Army. Image taken in Detroit, Michigan (1955) and featured in Life Magazine

-

Ignacy Paderewski mobilizing support for Poland by selling Christmas dolls at the Ritz Carlton in New York

-

John Sobieski, a lineal descendant of John III Sobieski, served in the U.S. Civil War and later made hundreds of speeches to prohibition-camps in the Midwest