History of Rwanda facts for kids

Human life in Rwanda likely began after the last ice age. By the 11th century, people had formed several small kingdoms. In the 1800s, King Rwabugiri of the Kingdom of Rwanda expanded his kingdom. He used military power and smart organization to control most of what is now Rwanda. Later, European powers like Germany and Belgium worked with the Rwandan court.

As people wanted to be free from colonial rule, and tensions grew between ethnic groups, Belgium granted Rwanda independence in 1962. Grégoire Kayibanda, a Hutu leader, became president. However, ethnic and political problems continued. In 1973, Juvénal Habyarimana, also a Hutu, took power. In 1990, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a group of Tutsi refugees, invaded Rwanda. This started the Rwandan Civil War, which made ethnic tensions even worse.

In 1994, President Habyarimana's plane was shot down. This event quickly led to the Rwandan genocide. During this time, hundreds of thousands of Tutsis and some moderate Hutus were killed. The Tutsi RPF then took control of Rwanda. Many Hutus fled to neighboring countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, creating large refugee camps. The RPF later invaded Congo to break up these camps, leading to the First Congo War in 1996. A second invasion started the Second Congo War, which involved many African nations and caused many deaths.

Contents

Early History: From Stone Age to Kingdoms

Rwanda has been a green and fertile land for thousands of years. It is believed that humans first lived here after the last ice age, around 10,000 years ago. The first people were likely the Twa, who were forest hunters and gatherers. Their descendants still live in Rwanda today.

Scientists have found signs of early settlements from the Stone Age. Later, people from the Iron Age lived here. They made tools from iron and a special kind of pottery.

Hundreds of years ago, a group called the Bantu, who were farmers and are the ancestors of today's Hutus, moved into the area. They started clearing forests to build their homes. Later, another group, mainly herders called Tutsi, also arrived. The exact story of how the Tutsi came to Rwanda is still debated. Old stories of the Kingdom of Rwanda say that the Rwandan people started about 10,000 years ago with a legendary king named Gihanga. He is said to have brought metalworking and other new technologies.

Middle Ages: Small States Form

By the 15th century, many Bantu-speaking groups, including Hutu and Tutsi, had formed small states. One of the oldest states was likely founded by the Renge people and covered most of modern Rwanda. Another state was called Mubari, and the Gisaka state in southeast Rwanda was also very strong.

The Kingdom Grows Strong (19th Century)

In the 1800s, the Rwandan kingdom became much stronger and more organized. It expanded its control, reaching the shores of Lake Kivu. This expansion often happened as Rwandan farmers and their way of life spread. When the kingdom grew, warrior camps were set up along the borders to protect against attacks. Only against strong states like Gisaka and Burundi was force mainly used.

Under the kings, the differences between Hutu and Tutsi became clearer. The Tutsis formed a ruling class led by a Mwami (king). The king was seen as a special, almost divine, leader who made the country successful. The sacred drum, called the Kalinga, was a symbol of the king's power.

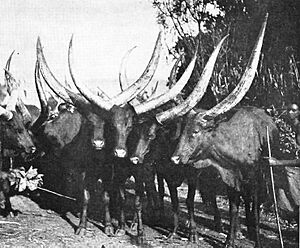

The king's wealth came from over a hundred large estates across the kingdom. These estates had banana fields and many cattle. The king and his helpers would travel between these estates, where his wives lived.

Everyone in Rwanda was expected to pay taxes to the king. These taxes were collected by Tutsi officials. Below the king were important Tutsi chiefs, including those who managed cattle, land, and the military. Below them were smaller Tutsi chiefs who governed different areas. Most of these chiefs were Tutsi.

Military chiefs were important for protecting the borders and raiding neighboring tribes for cattle. The biru, or "council of guardians," also advised the king on religious matters and court traditions. All these officials worked to support the king's power.

After the kingdom formed, the differences between Hutu and Tutsi became more fixed. King Rwabugiri's rule was strict, and taxes were high. The Tutsi leaders ruled with force, and only Tutsi men could be warriors. Hutus and Twa could help in fights but did not get the same warrior training. Young Tutsi men were taught that Tutsis were superior.

Because Tutsis had power and collected taxes from Hutu farmers, a system developed where Tutsis saw themselves as superior. Hutus became like second-class citizens. If Hutu farmers rebelled, they were punished harshly.

A traditional justice system called Gacaca helped solve problems and bring peace in many areas. The Tutsi king was the final judge. However, over time, this system became unfair to Hutus. For example, Tutsis who stole cattle from Hutus often went unpunished, while Hutus who stole from Tutsis could be sentenced to death.

The difference between the groups was not always strict. Tutsis who lost their cattle might be seen as Hutu. And Hutus who got cattle could become Tutsi. This process was called Kwihutura. But by the 1800s, it became very rare to change groups. This made the kingdom more like a caste system, where your group was fixed from birth. This social mobility ended completely when colonial rule began.

Colonial Rule in Rwanda

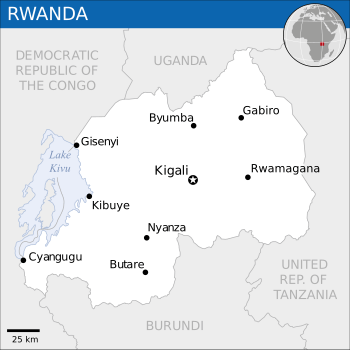

Unlike many parts of Africa, Rwanda was not divided up at the 1884 Berlin Conference. Instead, Rwanda and Burundi became part of the German Empire's colonial interests. After some border disputes, the final borders were set in 1900. These borders included the Kingdom of Rwanda and some smaller kingdoms.

In 1894, Rutarindwa became king after his father, Rwabugiri IV, died. But many in the king's council were unhappy. There was a rebellion, and the royal family was killed. Yuhi Musinga became king through his mother and uncles, but there was still disagreement.

German East Africa (1885–1919)

The first European to visit Rwanda was a German, Count Gustav Adolf von Götzen, in 1894. He traveled through Rwanda and visited King Rwabugiri's palace. The next year, the king died. With Rwanda in chaos, the Germans moved in to claim the region in 1897. Germany had few soldiers in German East Africa, so they did not change Rwandan society much.

German colonialists and missionaries arrived in 1897. Some Rwandans were unsure about the Germans, while others thought they might be better than being ruled by Buganda or the Belgians. The Germans supported a friendly government. Rwanda resisted German rule less than Burundi did.

German rule was indirect. They placed agents at the courts of local rulers. They did not push for modernization but did introduce cash taxes. They hoped this would make farmers grow crops they could sell, like coffee, to get money for taxes. This changed the economies in Rwanda and other nearby countries.

During this time, German officials believed that the Tutsi ruling class was racially superior to other native peoples in Rwanda. They thought Tutsis had "Hamitic" origins from the Horn of Africa, which they believed made them more "European" than Hutus. The Germans and powerful Catholic officials favored Tutsis because they were taller and seemed more "honorable." They gave Tutsis ruling positions.

Before colonial rule, Tutsis made up about 15-16% of the population. While many Hutus were poor farmers, some Hutus were part of the ruling class and even the monarchy.

German presence had mixed effects on Rwandan power. The Germans helped the king gain more control. But Tutsi power also weakened as trade grew and Rwanda connected more with outside economies. Hutus started to see money as a way to gain wealth and social standing, like cattle. The head-tax on all Rwandans also made Hutus feel less tied to their Tutsi leaders and more dependent on the Europeans. This tax suggested that everyone was equal, which slowly changed Hutu ideas.

By 1899, Germans had advisors at local chiefs' courts. Germany was busy fighting rebellions in Tanganyika. In 1911, the Germans helped the Tutsis put down a Hutu rebellion in northern Rwanda.

Belgian Rule (1916–1961)

After World War I, Belgium was given the task by the League of Nations to govern Rwanda and Burundi as one territory called Ruanda-Urundi. Belgium brought small independent kingdoms in western Rwanda under the central Rwandan court's power.

The Belgian government continued to use the Tutsi power structure to run the country. They also became more involved in education and farming. The Belgians introduced new crops like cassava, maize, and Irish potato to help farmers produce more food. This was important because of two severe famines in 1928–29 and 1943–44. During the second famine, known as the Ruzagayura famine, a large part of the population died. Many Rwandans also moved to neighboring Congo.

The Belgians wanted the colony to make money. They introduced coffee as a crop to sell and forced people to grow it. Farmers had to use a part of their fields for coffee. This was enforced by the Belgians and their local Tutsi allies. They used a system of forced labor called corvée, which had existed under King Rwabugiri. This forced labor was very unpopular in Rwanda. Hundreds of thousands of Rwandans moved to Uganda, which was richer and did not have the same policies.

Belgian rule made the ethnic differences between Tutsi and Hutu stronger. They supported Tutsi political power. European scientists at the time were interested in differences between people. They measured skulls and believed Tutsis were "superior" to Hutus because of their height and lighter skin. As a result, each person was given an identity card that said if they were Hutu or Tutsi. The Belgians gave most of the political control to the Tutsis. Tutsis began to believe they were superior and used their power over the Hutu majority.

In 1931, ethnic identity became official on administrative documents. Rwandans had to apply for identity cards and state their ethnicity: Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa. Most Rwandans were Hutu. But some people lied and said they were Tutsi, hoping for special benefits. Once recorded, the ethnic identity was fixed and passed down from fathers. About 84% were Hutu, 14% Tutsi, and 1% Twa. Each Rwandan had an ethnic identity card.

A history of Rwanda was written that supported these racial differences. However, no real historical or scientific evidence has been found to prove this official history. The differences between Tutsis and Hutus were similar to social class differences in other countries. For example, Tutsis, who raised cattle, traditionally drank more milk than Hutus, who were farmers.

The division of Hutu lands angered Mwami Yuhi IV, who wanted to strengthen his power and get rid of the Belgians. In 1931, Tutsi plots against the Belgians led to the Belgians removing Mwami Yuhi. Tutsis prepared to fight the Belgians but feared their military strength. Yuhi was replaced by his son, Mutara III. In 1943, he became the first king to become Catholic.

From 1935 onwards, "Tutsi," "Hutu," and "Twa" were written on identity cards. Because some Hutus were wealthy like Tutsis, the Belgians used a simple way to classify people: anyone with ten or more cattle was considered Tutsi. The Catholic Church, which ran most schools, also supported these differences. Most students in the 1940s and 1950s were Tutsi.

After World War II, Ruanda-Urundi became a United Nations trust territory under Belgium. In the 1950s, Belgium tried to bring in more democratic ideas, but Tutsi leaders resisted, seeing it as a threat to their power.

From the late 1940s, King Rudahigwa, a Tutsi, started reforms. He ended the "ubuhake" system and shared out cattle and land. This made Hutus feel more free from Tutsi rule. The reforms also meant Tutsis no longer had total control over cattle, which had been a sign of wealth. These changes increased ethnic tensions.

The Belgian identity cards made group identities stronger. Belgium also introduced elections by secret ballot. The Hutu majority gained a lot of power. The Catholic Church also began to speak out against Tutsi mistreatment of Hutus and promoted equality.

King Mutara tried to end the problems in the country. In 1954, he shared land between Hutu and Tutsi. He also agreed to end the forced labor systems (ubuhake and uburetwa) that Tutsis had used against Hutus.

Road to Independence: Growing Conflict

In the 1950s and early 1960s, a strong feeling of Pan-Africanism spread across Central Africa. This idea promoted African unity and equality. Hutu people, encouraged by this movement, the Catholic Church, and Christian Belgians, felt more resentment towards Tutsis. The United Nations and Belgian colonialists also added to the growing unrest.

Grégoire Kayibanda started the PARMEHUTU party, which led the Hutu "emancipation" movement. In 1957, he wrote the "Hutu Manifesto." His party quickly became more organized for fighting. In response, in 1959, the Tutsi formed the UNAR party, demanding immediate independence for Ruanda-Urundi with the Tutsi monarchy in charge. This group also became militarized. Small fights started between UNAR and PARMEHUTU groups.

In July 1959, the Tutsi King Mutara III Charles died after a vaccination. Some Tutsis believed he was killed. In November 1959, Tutsis tried to kill Kayibanda. Rumors that a Hutu politician, Dominique Mbonyumutwa, had been killed by Tutsis, led to violent revenge. This was called the "wind of destruction." Hutus killed many Tutsis. Thousands more, including the king, fled to Uganda before Belgian soldiers stopped the violence. Tutsi leaders accused the Belgians of helping the Hutus. A UN report said there was racism against Tutsis, similar to "Nazism."

The 1959 revolution changed Rwanda's politics greatly. About 150,000 Tutsis were forced to leave for other countries. Tutsis who stayed in Rwanda lost political power as Hutu power grew. Tutsi refugees also fled to Congo.

In 1960, Belgium agreed to hold local elections. The Hutu majority elected Hutu representatives. These changes ended the Tutsi monarchy, which had lasted for centuries. A Belgian attempt to create an independent Ruanda-Urundi with shared power between Tutsis and Hutus failed due to increasing violence. The UN then urged Belgium to divide Ruanda-Urundi into two separate countries: Rwanda and Burundi.

Independence (1962)

On September 25, 1961, Rwandans voted to become a republic instead of a monarchy. After elections, the first Rwandese Republic was declared, with Kayibanda as prime minister. Dominique Mbonyumutwa became the first president of the temporary government.

Between 1961 and 1962, Tutsi groups attacked Rwanda from neighboring countries. Rwandan Hutu troops fought back, and thousands more people were killed.

On July 1, 1962, Belgium granted full independence to Rwanda and Burundi. Rwanda became a republic ruled by the Hutu-majority MDR-Parmehutu party. In 1963, a Tutsi attack from Burundi led to another violent response by the Hutu government. About 14,000 people were killed. The economic ties between Rwanda and Burundi ended, and tensions between the two countries worsened. Rwanda became a Hutu-dominated one-party state. More than 70,000 people had been killed.

Kayibanda became Rwanda's first elected president. His government aimed for peaceful international relations, improving life for ordinary people, and developing Rwanda. He established relations with 43 countries, including the United States. However, by the mid-1960s, the government became less efficient and more corrupt.

The Kayibanda government set quotas to increase the number of Hutus in schools and government jobs. This hurt Tutsis, who were allowed only nine percent of secondary school and university spots, matching their population percentage. These quotas also applied to government jobs. With high unemployment, competition for these opportunities increased ethnic tensions. The Kayibanda government also continued the Belgian policy of requiring ethnic identity cards and discouraged "mixed" marriages.

After more violence in 1964, the government stopped political opposition. It banned the UNAR and RADER parties and executed Tutsi members. Hutu extremists used the term inyenzi (cockroaches) to insult Tutsi rebels. Hundreds of thousands of refugees moved to neighboring countries.

The Catholic Church worked closely with the Parmehutu party. Through the church, the government kept ties with supporters in Belgium and Germany. The country's two newspapers supported the government and were Catholic publications.

Military Rule

Quick facts for kids

Rwandese Republic

République Rwandaise (French)

|

|

|---|---|

| 1973–1994 | |

|

|

|

|

Motto: Liberté, Coopération, Progrès

(Liberty, Cooperation, Progress) |

|

|

Anthem: "Rwanda Rwacu"

(English: "Our Rwanda") |

|

|

|

| Capital | Kigali |

| Demonym(s) | Rwandan |

| Government | Unitary one-party presidential republic under a totalitarian military dictatorship |

| President | |

|

• 1973–1994

|

Juvénal Habyarimana |

| Legislature | National Development Council (1982-1994) |

| History | |

|

• Established

|

5 July 1973 |

| 1990–1994 | |

|

• Disestablished

|

6 April 1994 |

| Area | |

|

• Total

|

26,338 km2 (10,169 sq mi) |

| HDI (1994) | 0.192 low |

| Currency | Rwandan franc |

| ISO 3166 code | RW |

| Today part of | Rwanda |

On July 5, 1973, Defence Minister Maj. Gen. Juvénal Habyarimana overthrew President Kayibanda. He stopped the constitution, closed the National Assembly of Rwanda, and banned all political activity.

At first, Habyarimana ended the quota system, which made Tutsis happy. But this did not last. In 1974, people complained that Tutsis had too many jobs in fields like medicine and education. Thousands of Tutsis were forced to leave their jobs, and many had to leave the country. In related violence, several hundred Tutsis were killed. Slowly, Habyarimana brought back many of his predecessor's policies that favored Hutus over Tutsis.

In 1975, President Habyarimana formed the National Revolutionary Movement for Development (MRND). Its goals were to promote peace, unity, and national development. This movement was organized from local areas up to the national level.

Under the MRND, a new constitution was approved in 1978. It made Rwanda a totalitarian one-party state under the MRND. Habyarimana, as president of the MRND, was the only candidate in the presidential elections. He was re-elected in 1983 and 1988, always as the only candidate. However, voters could choose between two MRND candidates for the National Development Council of Rwanda. In July 1990, President Habyarimana announced he would change Rwanda into a multi-party democracy.

Connection to Events in Burundi

The situation in Rwanda was greatly affected by events in Burundi. Both countries had a Hutu majority, but Burundi had a Tutsi-controlled army government for decades. After the assassination of Louis Rwagasore, his UPRONA party split into Tutsi and Hutu groups. A Tutsi Prime Minister was chosen, but in 1963, the king had to appoint a Hutu prime minister, Pierre Ngendandumwe, to calm Hutu unrest. However, the king soon replaced him with another Tutsi prince.

In Burundi's first elections after independence in 1965, Ngendandumwe was elected Prime Minister. He was immediately killed by a Tutsi extremist. Hutus won most seats in national elections a few months later, but the king canceled the results. The Tutsi-dominated army, led by Michel Micombero, responded brutally. Almost all Hutu politicians were killed. Micombero took control, removed the new Tutsi king, and ended the monarchy. He then threatened to invade Rwanda. A military dictatorship lasted in Burundi for 27 more years.

More violence occurred in Burundi between Hutus and Tutsis from 1965 to 1972. In 1969, the Tutsi military again removed Hutus from power. Then, a Hutu uprising in 1972 was met with a fierce response by the Tutsi-dominated Burundi army. This event, known as the Burundi genocide of Hutus, killed nearly 200,000 people.

This violence led to more Hutu refugees from Burundi fleeing into Rwanda. Now there were many Tutsi and Hutu refugees across the region, and tensions continued to rise.

In 1988, Hutu violence against Tutsis in northern Burundi started again. In response, the Tutsi army killed about 20,000 more Hutus. Again, thousands of Hutus were forced to flee to Tanzania and Congo to escape another genocide.

Civil War and Genocide

Many Rwandan Tutsi refugees in Uganda had joined the rebel forces of Yoweri Museveni. They became part of the Ugandan military after the rebels won in 1986. Among these were Fred Rwigyema and Paul Kagame. They became important leaders in the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a Rwandan rebel group mostly made up of Tutsi veterans from the Ugandan war.

On October 1, 1990, the RPF invaded Rwanda from Uganda. The rebel group, mostly Tutsis, said the government was not becoming democratic enough and not solving the problems of about 500,000 Tutsi refugees living outside Rwanda.

The Tutsi invasion increased ethnic tensions to a very high level. After three years of fighting and several cease-fires, the government and the RPF signed a "final" peace agreement in August 1993. This was called the Arusha Accords, and it aimed to create a power-sharing government. But this plan immediately faced problems.

The situation worsened when the first elected Burundian president, Melchior Ndadaye, a Hutu, was killed by the Burundian Tutsi-dominated army in October 1993. In Burundi, a fierce civil war then started between Tutsis and Hutus. This conflict spread into Rwanda and made the fragile peace agreement unstable. Tutsi-Hutu tensions quickly grew stronger. The UN sent a peacekeeping force called United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), but it did not have enough money or staff to handle the two-country civil war.

The 1994 Genocide in Rwanda

On April 6, 1994, the airplane carrying Juvénal Habyarimana, the President of Rwanda, and Cyprien Ntaryamira, the Hutu President of Burundi, was shot down as it was about to land in Kigali. Both presidents died in the crash.

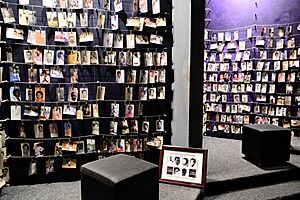

Military and militia groups immediately began gathering and killing Tutsis and moderate Hutus. The killings quickly spread across the country. Between April 6 and early July, a very fast genocide occurred. Between 500,000 and 1,000,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed by organized militia groups called Interahamwe. Local officials even told ordinary citizens to kill their Tutsi neighbors. Local radio stations spread hate speech, calling Tutsis Inyenzi (cockroaches). The president's MRND Party was involved in organizing much of the genocide.

The RPF restarted its civil war against the Rwandan Hutu government when they heard about the mass killings. Their leader Paul Kagame directed RPF forces to advance. The civil war happened at the same time as the genocide for two months. The Tutsi-led RPF continued to move towards the capital and by June, they controlled the northern, eastern, and southern parts of the country. Thousands more civilians were killed in the fighting. UN member countries did not send more troops or money to UNAMIR. France occupied the remaining part of the country in an operation called Turquoise. While this operation stopped some killings, some say it allowed Hutu militias to escape.

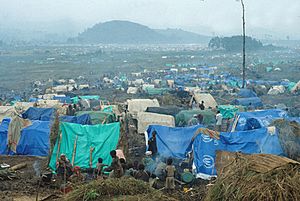

Rwanda After the Civil War

Between July and August 1994, Kagame's Tutsi-led RPF troops entered Kigali and soon captured the rest of the country. The Tutsi rebels defeated the Hutu government and ended the genocide. However, about two million Hutu refugees, some of whom had taken part in the genocide and feared Tutsi revenge, fled to neighboring countries like Burundi, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zaire. This huge movement of people became known as the Great Lakes refugee crisis.

After the Tutsi RPF took control of the government in 1994, Kagame formed a government of national unity. A Hutu president, Pasteur Bizimungu, was chosen. Kagame became Minister of Defence and Vice-President of Rwanda and was the real leader of the country.

Following an uprising by ethnic Tutsis in eastern Zaire in October 1997, many refugees began to return to Rwanda. More than 600,000 came back in two weeks in November. Then, in December 1996, another 500,000 returned from Tanzania. It is thought that fewer than 100,000 Rwandans remain outside Rwanda. These are believed to be remnants of the defeated army and militias from the former government. There are also many innocent Hutus in the forests of eastern Congo who have been told they will be killed if they return to Rwanda. Rebels also use force to stop these people from returning.

In northwest Rwanda, Hutu militia members killed three Spanish aid workers and three soldiers on January 18, 1997. Since then, most refugees have returned, and the country is safe for tourists.

Rwandan coffee became famous after international tests showed it was among the best. Rwanda now earns money from coffee and tea exports. However, the main source of income is tourism, especially visiting mountain gorillas. Other parks like Nyungwe Forest and Akagera National Park are also popular. Lakeside resorts in Gisenyi and Kibuye are also growing.

When Bizimungu criticized the Kagame government in 2000, he was removed as president, and Kagame took over. Bizimungu started an opposition party, but it was banned. Bizimungu was arrested in 2002 for treason and sentenced to 15 years in prison. He was released by a presidential pardon in 2007.

The government after the war has focused on development. They have brought water to remote areas, provided free education, and created environmental policies. There is little corruption in the country. Rwanda is one of the least corrupt countries in Africa.

Hutu leaders involved in the genocide were put on trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, in Rwandan courts, and through the informal Gacaca program. Gacaca is a traditional way of solving conflicts at the village level. Community members elect elders to be judges, and the whole community is present. This system was changed to try those who committed killings or theft but did not organize the massacres. Prisoners, dressed in pink, stood trial before their communities. Judges gave sentences, from returning to prison to working for victims' families. Gacaca officially ended in June 2012. For many, Gacaca helped bring closure, and prisoner testimonies helped families find victims.

Ethnicity has been officially outlawed in Rwanda to promote healing and unity. People can be tried for discussing different ethnic groups.

Rwanda is a focus country for the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The United States provides AIDS programs, education, and treatment. Rwandans with HIV can now get free medicines and food packages.

First and Second Congo Wars

To protect Rwanda from the Hutu Interahamwe forces that had fled to eastern Zaire, RPF forces invaded Zaire in 1996. Rwanda allied with Laurent Kabila, a revolutionary in eastern Zaire who was an enemy of Zaire's dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko. Ugandan forces also supported Kabila's AFDL (Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo) forces. This became known as the First Congo War.

In this war, armed Tutsi groups in eastern Zaire, known as Banyamulenge, allied with the Tutsi RDF forces against the Hutu refugees in the North Kivu area, which included the Interahamwe militias.

Kabila's main goal was to remove Mobutu. He moved his forces to Kinshasa, and in 1997, he captured Kinshasa and became president of Zaire. He then renamed it the Democratic Republic of the Congo. With his success, Kabila no longer wanted an alliance with the Tutsi-RPF Rwandan army and Ugandan forces. In August 1998, he ordered both armies out of the DRC. However, neither Rwanda nor Uganda intended to leave, which set the stage for the Second Congo War.

During the Second Congo War, Tutsi militias in Congo's Kivu province wanted to join Rwanda. Kagame also wanted this to increase Rwanda's resources and add the Tutsi population from Kivu back into Rwanda. This would strengthen his political base and protect the local Tutsis who had also suffered massacres.

In the Second Congo War, Uganda and Rwanda tried to take much of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from Kabila's forces. They almost succeeded. However, the DRC was a member of the SADC (Southern Africa Development Community). President Laurent Kabila asked this group for help. Armies from Angola and Zimbabwe were sent to aid Kabila. These armies were able to push back Rwanda's and Uganda's forces.

In the large conflict between 1998 and 2002, Congo was divided into three parts. Many armed groups called Mai Mai appeared. They were supplied by arms dealers from around the world. Over 5.4 million people died in the conflict, as well as most animals in the region.

Laurent Kabila was killed in the DRC in 2001. His son, Joseph Kabila, took over. Joseph spoke French, English, and Swahili. He studied in Tanzania and Uganda and trained in China. After serving as transitional president for five years, he was freely elected president of Congo in 2006.

Ugandan and Rwandan forces in Congo began fighting each other for territory. Congolese Mai Mai militias, active in the Kivu provinces where most refugees were, used the conflict to settle local scores. They fought each other, Ugandan and Rwandan forces, and even Congolese forces.

The war ended when, under Joseph Kabila's leadership, a ceasefire was signed. Talks were held in South Africa to decide on a two-year transition period and organize fair elections.

Rwandan RPF troops finally left Congo in 2002. They left behind widespread disease and malnutrition that continued to kill thousands each month. However, Rwandan rebels still operate in northeast Congo and the Kivu regions. These are said to be remnants of Hutu forces who cannot return to Rwanda without facing genocide charges. They are not welcomed in Congo and are pursued by DRC troops. In the first six months of 2007, over 260,000 civilians were forced to leave their homes. Congolese Mai Mai rebels also continue to threaten people and wildlife. While a large effort to disarm militias has been successful with UN help, some militias were still being disarmed in 2007. Fierce fights between local tribes in the Ituri region, who were drawn into the Second Congo War, still continue.

Rwanda Today

Rwanda today is working to heal and rebuild. It shows signs of fast economic development, but there are growing international concerns about human rights.

Economically, Rwanda mainly exports to Belgium, Germany, and China. In April 2007, Belgium and Rwanda signed a trade agreement. Belgium gives Rwanda €25–35 million each year. Belgian cooperation helps develop farming practices in Rwanda. It has given out tools and seeds to help rebuild the country. Belgium also helped restart fishing in Lake Kivu.

In Eastern Rwanda, the Clinton Hunter Development Initiative and Partners in Health are helping to improve farming, water, sanitation, and health services. They also help connect Rwandan farmers to international markets. Since 2000, the Rwandan government wants to change the country from farming to a knowledge-based economy. They plan to provide high-speed internet across the whole country.

Rwanda applied to join the Commonwealth of Nations in 2007 and 2009. This shows it is trying to move away from French influence. It was accepted in 2009. This membership helps "strengthen the rule of law and support the Rwandan Government's efforts towards democracy and economic growth." Rwanda also joined the East African Community in 2009, along with Burundi.

However, Freedom House rates Rwanda as "not free." Political rights and civil liberties are decreasing. In 2010, Amnesty International criticized attacks on Rwandan opposition groups before presidential elections. For example, Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza, president of the FDU-Inkingi party, and her aide were attacked in February 2010. In April, Human Rights Watch's researcher was denied a work visa. The only new opposition party to register, PS-Imberakuri, had its presidential candidate, Bernard Ntaganda, arrested in June. He was charged with "genocide ideology" and "divisionism."

Rwandan Green Party President, Frank Habineza, also reported threats. In October 2009, a Green Party meeting was broken up by police. Authorities prevented the party from registering or running a candidate in the presidential election. Weeks before the election, on July 14, 2009, André Kagwa Rwisereka, the vice president of the opposition Democratic Green Party, was found dead with his head nearly cut off.

Public review of government policies is limited by press freedom. In June 2009, journalist Jean-Leonard Rugambage was shot dead outside his home. His newspaper was investigating an attempted murder of a former Rwandan general. In July 2009, Agnes Nkusi Uwimana, editor of "Umurabyo" newspaper, was charged with "genocide ideology." As the presidential election neared, two other newspaper editors left Rwanda.

The United Nations, European Union, the United States, France, and Spain have publicly expressed concerns about these issues.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Ruanda para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Ruanda para niños

- History of Africa

- History of Burundi

- List of kings of Rwanda

- List of presidents of Rwanda

- Politics of Rwanda

- Prime Minister of Rwanda

- Ruanda-Urundi

- Rwanda

- Kigali history and timeline

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |