History of aesthetics facts for kids

Aesthetics is all about what we find beautiful and why. It's about understanding art, nature, and even everyday things that make us feel something special. This article explores how people throughout history have thought about beauty and art.

Contents

Ancient Greek Ideas on Beauty

The first big ideas about beauty came from ancient Greek thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, and Plotinus. It's interesting to know that the Greeks might not have had a single word exactly like our "beauty."

Xenophon and Socrates thought beauty was linked to what was useful or good. For them, something was beautiful if it served a purpose, like helping people. Socrates even said that beauty was relative, meaning it could be different for everyone.

Plato's View of Absolute Beauty

Plato had a different idea. He believed in an "absolute beauty" that existed on its own, like a perfect idea or "Form." This true beauty wasn't just found in things we see. It was a pure idea that beautiful objects only copied.

Plato thought that love (Eros) made people want to reach this pure idea of beauty. He also connected beauty with truth and goodness. For Plato, beauty often meant having good proportions, harmony, or unity in parts. He even thought a beautiful mind combined with a beautiful body was the highest beauty.

However, Plato wasn't a big fan of art. He saw it as just an imitation of things, which he felt took people further away from true understanding. He even suggested that poets should be carefully watched in his ideal society!

Aristotle's Principles of Beauty

Aristotle had more positive views on art than Plato. He believed that beauty came from order, symmetry, and clear definition. He also added that a beautiful object needed to be a certain size – not too big or too small.

Aristotle also thought that the pleasure we get from beauty doesn't come from wanting something. He saw art as giving immediate pleasure, different from useful things. He believed art was more philosophical than history because it explored what was possible and necessary, not just what happened.

Plotinus and Spiritual Beauty

Later, Plotinus, a Neo-Platonist, added to these ideas. He thought that a "creative reason" shaped matter into beautiful forms. The more something was shaped by this reason, the more beautiful it was.

Plotinus believed there were different levels of beauty. The highest was human reason, then the human soul, and finally, real objects, which were the lowest. He also said that a single, simple thing could be beautiful just by being unified. He even thought artists could create things more beautiful than nature itself by using their ideas.

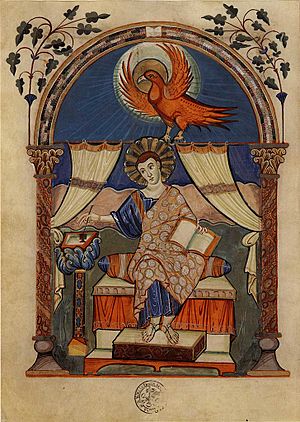

Western Medieval Aesthetics

During the Middle Ages, most art was religious. It was often paid for by the Church or powerful leaders. These artworks, like chalices or church buildings, were used in religious services. They were often made from expensive materials like gold and lapis lazuli.

Medieval thinkers built on classical ideas but added religious meaning. St. Bonaventure believed that artistic skills were gifts from God. He thought art helped people understand God through different "lights" of knowledge.

Saint Thomas Aquinas had a very famous theory of beauty. He didn't write one big book on it, but scholars have put his ideas together. Aquinas believed beauty had three main parts:

- Integrity or perfection: The object is complete and whole.

- Proportion: The parts of the object fit together well.

- Brightness or form: The object shines with clarity and light.

Aquinas's ideas were very important and influenced many later thinkers. As the Middle Ages ended and the Renaissance began, art started to change its focus and style.

Baroque and Neoclassicism

In the 1600s, new art styles like Baroque challenged older ideas about beauty, like perfect proportion and harmony. Baroque art focused on new ideas and techniques.

Tesauro's Ideas on Wit

Emanuele Tesauro wrote an important book in 1654 called Il Cannocchiale aristotelico (The Aristotelian Telescope). He talked about key Baroque ideas like "conceit" (a clever idea), "wit" (sharp intelligence), and "wonder." Tesauro believed that metaphor (comparing two unlike things) was a powerful way to understand truth.

Bellori and Ideal Beauty

Giovanni Pietro Bellori, an art theorist, gave a famous lecture in 1664. He talked about the "Idea" of the artist. Influenced by Plotinus, Bellori thought that artists should look beyond nature to a perfect "Idea" of beauty.

Bellori's ideas were very important for the concept of "ideal beauty." He influenced later thinkers like Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who also wrote about ideal beauty in ancient art. Bellori's ideas helped spread the concept of ideal beauty throughout Europe.

Age of Enlightenment

The Enlightenment was a time when people focused on reason and individual thought. This also changed how they thought about beauty.

Addison on Imagination

Joseph Addison wrote about the "pleasures of imagination." He said these pleasures come from what we see. There are primary pleasures (from objects right in front of us) and secondary pleasures (from ideas of visible objects). He also noted how our experiences affect what we find beautiful.

Shaftesbury and Inner Sense

Shaftesbury believed that beauty and goodness were connected, much like Plato. He thought that the order of the world, where all beauty truly lives, was spiritual. We don't see beauty with our eyes, but with an "internal or moral sense" that also understands what is good. This feeling brings true spiritual joy.

Hutcheson's Uniformity in Variety

Francis Hutcheson agreed with some of Shaftesbury's ideas but said that beauty is always related to the mind that sees it. He believed that beauty wasn't just a simple feeling like color. Instead, it came from "uniformity amidst variety"—meaning order among different parts.

He called the ability to see this "an internal sense." This sense gives us immediate pleasure, and a beautiful thing is always beautiful, whether we want it to be or not. He also talked about "absolute" beauty (in an object itself) and "relative" beauty (when an object imitates something else).

Baumgarten and "Aesthetics"

Baumgarten was a German philosopher who actually coined the term "aesthetics." For him, beauty was perfect "sense-knowledge." He thought that nature was the most beautiful thing, and art should try to imitate nature as closely as possible.

Burke on Sublime and Beautiful

Edmund Burke explored the "Sublime" and the "Beautiful." He saw beauty in smallness, smoothness, gentle curves, delicacy, and bright, pure colors. The "sublime," for Burke, was something that caused a feeling of awe mixed with a bit of terror, like the feeling of infinity.

Kant's Subjective Beauty

Immanuel Kant had a very important theory about beauty. He believed that beauty doesn't exist *inside* an object. Instead, it's the pleasure we get when our imagination and understanding work freely together because of an object. When we feel this pleasure, we call the object beautiful.

This pleasure is more than just liking something. It's "disinterested," meaning it doesn't depend on whether the object is useful to us. Even though the feeling of beauty is personal, Kant thought that if something is beautiful to him, he also believes it should be beautiful for everyone else. He also said that judging beauty is always about a single object, like "This rose is beautiful." For Kant, nature was the best example of beauty, even more so than art.

German Thinkers

After Kant, German philosophers continued to explore aesthetics in new ways.

Schelling and Art as Revelation

Schelling was the first to try to create a full "Philosophy of Art." He believed that art was special because it showed the connection between the viewer and the object. He thought art could reveal the "absolute" (a perfect, complete reality) even better than philosophy or nature.

Hegel's Absolute Spirit

Hegel saw art as the first step of the "absolute spirit." He believed that beauty was the "ideal" showing itself through our senses. For Hegel, art was the highest way to reveal beauty because it made ideas clearer and showed the spiritual life in the world. He even classified arts from architecture (lowest) to poetry (highest).

Herbart and Formalism

Herbart tried to move away from Kant's idea of beauty being purely subjective. He believed that beauty came from certain "aesthetic relations" between parts of an object. He is known as a "formalist" because he focused on these abstract relationships. He thought that just like music has rules for harmony, other arts could have similar rules for beauty.

Lessing on Art's Boundaries

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing explored the specific purpose of different art forms. He famously distinguished between arts that use space (like painting) and arts that use time (like poetry and music). He also tried to find clear rules for poetic truth, building on Aristotle's ideas.

Goethe and Schiller

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote many thoughts on beauty, trying to combine the idea of ideal beauty with real-world examples. Schiller looked at art from the perspective of human nature and culture. He believed that art could help bring together our senses and our reason. He also connected aesthetic activity with the human desire to play.

German Scientists' Contributions

Some German scientists tried to understand how our bodies react to beauty. Hermann von Helmholtz studied how we hear musical tones. Others tried to do the same for colors, but it was harder to find exact rules. Gustav Fechner even did experiments to see if people preferred the "golden section" (a specific proportion) in art, and his results suggested they did.

French Writers

In France, ideas about aesthetics often came from discussions among poets and critics.

Boileau in the 17th century, and later Fontenelle and Charles Perrault, debated whether modern art was better than ancient art. In the 18th century, thinkers like Voltaire, Bayle, and Diderot continued to discuss the goals of poetry and art. These discussions gave later theorists valuable insights into aesthetic experiences. Charles Batteux also classified arts based on whether they used space or time, similar to Lessing.

African Aesthetics

African art is incredibly diverse and has a long history. It's shaped by thousands of years of changes, trade, and cultural traditions. Some people in African cultures don't even have a direct word for "art." For example, the Dagara people of Burkina Faso use a word that means "sacred" instead. This shows that many African artworks, like Kongo nkisi objects, were made for spiritual or healing purposes, not just for looking at.

African cultures often blend usefulness with beauty. Things like Akan stools, Yoruba cloth, and Gio spoons are everyday objects that are also beautiful. Sculpture and performance art are very important, and abstract forms were valued long before Western influence. The Nok culture is an ancient example of this. The mosque of Timbuktu also shows unique African styles.

Egyptian Aesthetics

The idea of ma'at was central to ancient Egypt and strongly connected to their art. Ma'at meant order, balance, justice, and truth in the world. It was also a goddess who represented these ideas. Egyptian artists tried to create art that showed this order and balance. They used specific colors and proportions to follow ma'at.

Artworks and buildings in ancient Egypt aimed to reflect this balance in their designs. For example, in paintings and carvings, people were shown with clear proportions to symbolize harmony and beauty. Art helped keep ma'at alive by sharing ideas about the universe, spiritual messages, and moral values. By making beautiful and meaningful art, Egyptians helped keep society and the universe in balance.

Yoruba Aesthetics

The word ẹwà is very important in the Yoruba culture of West Africa. It describes beauty and aesthetic quality in art and culture. But ẹwà is more than just visual beauty; it also includes feelings and spiritual meaning. In Yoruba culture, beauty isn't just on the surface. It's connected to deeper values.

Being ẹwà also means being true to yourself and living in harmony with your values and spiritual beliefs. It means being in tune with your inner self. Yoruba beauty is often linked to harmony, balance, and good proportions. Artworks that are considered ẹwà are well-balanced, create strong feelings, and fit with Yoruba art traditions. This applies to sculptures, masks, textiles, and buildings.

Americas

Aztec Aesthetics

Teōtl was the Aztecs' word for the supreme divine force that underlies the whole world. It was a powerful force present in everything, creating and maintaining balance in the universe. In Aztec art, creations were beautiful if they truly showed teōtl. This meant that artworks were considered true and beautiful when they honestly represented this divine force, its balance, and its purity. Teōtl was the very basis of what the Aztecs considered beautiful in art.

Teōtl was not just about beauty; it was also about morals and knowledge. In Aztec thinking, what was beautiful was also good and true. Creative works were considered good if they had a deep connection to teōtl. Teōtl also represented balance and purity, which were key ideals in Aztec art. Beautiful creations showed balance and purity, helping to keep the universe in order.

The idea of hózhǫ́ǫ́g (sometimes spelled "hozho") is very important in Navajo culture. It's a deep connection to beauty and balance in all parts of life, not just art. Hózhǫ́ǫ́g is a way of living in harmony with yourself, other people, and the world. It's also linked to the Navajo people's identity and their ability to keep their culture alive. By creating art that fits with hózhǫ́ǫ́g, they pass on their values to future generations.

Hózhǫ́ǫ́g emphasizes a strong connection with nature. The Navajo people see nature as a source of beauty and ideas. Many patterns in Navajo art, like stars, feathers, and plants, come from nature. Hózhǫ́ǫ́g is also tied to their spiritual beliefs. It means being in harmony with spiritual forces. Artworks are sometimes used to talk with the supernatural and honor gods and spirits.

Asia

Arab Aesthetics

Arab art is often seen in the context of Islam, which began in the 7th century. It's sometimes called Islamic art, even though many Arab artists throughout history were not Muslim. "Islamic art" refers to art made by people in an Islamic culture or setting, whether the artist is Muslim or not.

Islamic art often includes non-religious elements. While some Islamic thinkers discourage showing human and animal forms in religious art, these forms have appeared in secular art in almost all Islamic cultures. The idea that creating living forms is only for God led to some debate about images. The strongest rules against showing figures are in the Hadith (sayings of the Prophet), which warns artists who "breathe life" into their creations. The Qur'an also condemns idol worship. Because of this, figures in paintings were often stylized, and sometimes figurative artworks were even destroyed.

However, human images can be found in early Islamic cultures, with different levels of acceptance. Showing humans for worship is always forbidden. Arabic writing itself is an art form. It's written from right to left and has 28 letters. The letters change slightly depending on where they are in a word, but their main shape stays the same.

Chinese Aesthetics

Chinese art has a long and varied history. Confucius believed that arts like music and poetry helped people grow and understand what's important about being human. But his opponent, Mozi, argued that music and fine arts were wasteful and only benefited the rich. By the 4th century AD, artists started writing about the goals of art. Gu Kaizhi wrote books on painting theory.

Many later Chinese artists and scholars both created art and wrote about it. Religious and philosophical ideas often influenced art, but not always. Modern Chinese aesthetic theory developed in the early 20th century. Thinkers like Kant and Hegel have influenced contemporary Chinese aesthetic ideas.

Indian Aesthetics

Indian aesthetics goes back to ancient texts like the Vedic texts of Hinduism. The Aitareya Brahmana (around 1000 BCE) says that arts help refine the self. The oldest complete Sanskrit text on aesthetics is the Natya Shastra (around 200 BCE to 200 CE). This text describes the theory of rasa.

Rasa is an ancient idea in Indian arts about the "flavor" of a visual, literary, or musical work. It creates an emotion or feeling in the audience that can't be fully described. According to the Natya Shastra, the goal of art is to create an aesthetic experience and deliver emotional rasa. Art can bring peace and relief to those who are tired or sad. But entertainment isn't the main goal. The main goal is to create rasa to uplift and transport the audience to a higher understanding.

The philosopher Abhinavagupta (around 1000 CE) gave the most complete explanation of aesthetics in Indian drama and music. The concept of rasa is key to many Indian art forms, including dance, music, theater, painting, and literature. How rasa is used can differ between styles. In Indian classical music, each raga (musical scale) is made to create a specific mood or rasa in the listener.

In Indian ideas about poetry, scholars discuss both what is said and how it is said (words, grammar, rhythm). This means both the meaning of the text and the experience of rasa are important. In Indian sculpture and architecture (Shilpa Shastras), the rasa theories influence the shapes, arrangements, and expressions in images and buildings.

Japanese Aesthetics

An important idea in Japanese aesthetics is wabi-sabi. This philosophy values the beauty of things that are simple, imperfect, and temporary. It finds beauty in things that have naturally aged. "Wabi" means solitude and simplicity, while "sabi" describes the beauty that comes with age and wear.

Emptiness, or "sabi," is also a key part of wabi-sabi. It means having space or a pause in an artwork that lets the viewer think. Minimalism is a big part of Japanese aesthetics, focusing on reducing things to their basic parts. This can be seen in Japanese architecture, design, and art.

A crucial part of wabi-sabi is accepting that things change and age. Objects with signs of age, like cracks or stains, are seen as beautiful because they tell the story of the object's life. This idea is important in Japanese art and crafts, like ceramics. Wabi-sabi also includes balance and asymmetry. Instead of perfect symmetry, uneven and irregular forms are appreciated in art and garden design to create a natural feeling of movement and balance.

Oceania

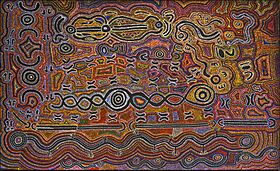

Aboriginal Aesthetics

Dadirri is a concept from Aboriginal cultures in northern Australia. It describes a deep, quiet way of listening and reflecting to connect with the land and spirituality. Dadirri is a form of aesthetics that means appreciating the beauty and meaning of nature and spirituality through silence. It includes seeing beauty in natural patterns, colors, sounds, and shapes. This aesthetic dimension means seeing beauty in simple, everyday things.

For many Aboriginal cultures, art is a way to express dadirri. Many Aboriginal artworks, like paintings, baskets, and textiles, show the beauty and spirituality of nature and the land. These artworks are not just beautiful; they also carry deep symbolic and spiritual meanings. Dadirri is also about feeling a deeper connection with nature and the spiritual side of life. This connection goes beyond just seeing things. It's about experiencing a beautiful spiritual presence.

Western Aesthetics Today

Western ideas about aesthetics often start with ancient Greek philosophers. As we saw, Plato believed in beauty as a perfect "form," and that beautiful objects had proportion, harmony, and unity. Aristotle also thought beauty came from order, symmetry, and clear definition.

From the late 1600s to the early 1900s, Western aesthetics went through a big change, leading to what is called modernism. German and British thinkers focused on beauty as the main part of art and aesthetic experience. They believed art should aim for absolute beauty.

See also