History of the Canadian Army facts for kids

The Canadian Army is the land part of the Canadian Armed Forces. Its official name, "Canadian Army," started being used in November 1940 during the Second World War. Even when it was called "Mobile Command" or "Land Force Command" between 1968 and 2011, people still often called it the "Canadian Army." This name has been used for Canada's ground forces since 1867, when Canada became a country. On August 16, 2011, the name "Canadian Army" was officially brought back.

Contents

How the Canadian Army Started

Before Canada became a country in 1867, its defence depended on the armies of other countries. For example, New France relied on the French Royal Army. Later, English and British colonies like Newfoundland and Nova Scotia depended on the British Army. After the British took over New France in 1760, areas like present-day Ontario and Quebec also relied on the British Army. Local soldiers and Canadian militia helped these armies. Many of these groups were active only during wars.

During the War of 1812, local Canadian groups, including fencibles (soldiers for local defence) and militia from different parts of Canada, fought alongside the British Army. These Canadian units were very important in the war. Many current Canadian Army units keep the history and battle honours from these early groups.

Canada later developed a volunteer militia, which were part-time soldiers. But the country still relied on British soldiers and the Royal Navy for defence. The Canadian Militia grew from British forces in North America. In 1854, during the Crimean War, most British soldiers left Canada. This made some American politicians think it was a good time to take over British North America. So, the government of the United Canadas (now Ontario and Quebec) passed the Militia Act of 1855. This law created an "active militia" of 5,000 men, which was like a professional army. The Canadian Army today is a direct descendant of this force.

When Canada became a country in 1867, its ground forces were still called the Militia. The Militia Act of 1868 combined the militias of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia with that of the United Canadas. By February 1869, the Militia had over 37,000 active soldiers and nearly 619,000 in reserve.

Early Challenges for the Militia

The new militia first saw action against the Fenians. These Irish radicals tried to invade parts of southern Canada from the United States in the late 1800s. The Canadian militia was quite strong during these raids in the 1860s and 1870s. In 1866, the Fenians defeated the Canada West militia at the Battle of Ridgeway because the militiamen were new to fighting. But in 1870, the Quebec militia easily pushed back the Fenians at Trout River and Eccles Hill.

In 1869, Canada bought a huge area called Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company. This land included much of northern Canada today. The 10,000 people living there, many of them Métis in the Red River Colony, were not asked about this sale. Led by Louis Riel, they rebelled and set up their own government to join Canada on their own terms. A deal was made, but the execution of a man named Thomas Scott by the Métis angered many in Ontario.

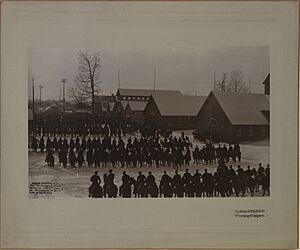

To calm things down, an expedition was sent to end the Red River Rebellion. In 1870, a force of British and Ontario militiamen, led by General Garnet Wolseley, marched to the Red River colony. Riel fled, and the rebellion ended without a fight. Manitoba became Canada's fifth province.

British Troops Leave Canada

After the Treaty of Washington (1871) and the end of the Fenian raids, Britain started to remove its soldiers from Canada. This was partly to send troops to other parts of the British Empire and partly because relations with the United States were friendlier. By 1871, most British garrisons (military posts) were gone, except for Halifax and Esquimalt. After 1871, Canada's government was responsible for its own defence.

This led to the creation of the Permanent Active Militia, which was Canada's regular army of full-time professional soldiers. There was also the Non-Permanent Active Militia (reserves), who were part-time soldiers. Canada usually spent as little as possible on defence, so the cheaper non-permanent militia was preferred.

In 1876, the Royal Military College of Canada was founded to train officers for the Permanent Active Militia. British Army officers still served as senior commanders because there weren't enough Canadian officers. The first permanent military units, 'A' and 'B' Batteries of Garrison Artillery, were formed in 1871. These are now part of the 1st Regiment Royal Canadian Horse Artillery. The Cavalry School Corps (now The Royal Canadian Dragoons) and the Infantry School Corps (now The Royal Canadian Regiment) were both formed in 1883.

Militia Challenges and Reforms

The militia became less active after the Fenian threat ended in the 1870s. Their main job was to help civil authorities, often putting down riots between Catholics and Orangemen. Both Conservative and Liberal governments used militia officer positions to reward political supporters. This meant many officers were chosen for political reasons, not military skill. Most militiamen served only 12 days a year. British officers often criticized the militia for being poorly trained and led by political officers.

The North-West Field Force was a group of militia and regular troops formed to stop the North-West Rebellion of 1885. This was Canada's first military action without direct British troop support. Colonel Ivor Herbert, a British officer who later commanded the militia, pushed for reforms. He created a quartermaster general position to handle supplies and increased spending on the Permanent Force. He also started new regiments like the Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry and the Royal Canadian Dragoons. However, Herbert's reforms upset powerful militia colonels who were also Members of Parliament, and he was dismissed in 1894.

Canada sent its first soldiers overseas in 1885 for the Nile Expedition. These "Nile Voyageurs" were Canadian volunteers who helped British forces in Sudan by working as boatmen.

In 1896, Sir Wilfrid Laurier became Prime Minister and appointed Sir Frederick Borden as Defence Minister. Borden was a reformer who appointed Colonel Edward Hutton of the British Army as militia commander. During this time, the Permanent Force gained new specialized units like engineers, medical, transport, and intelligence corps.

The Boer War and Canadian Identity

In 1899, war threatened between the Transvaal (in South Africa) and Britain. Many English-Canadians expected Canada to fight with Britain, while French-Canadians were against it. Prime Minister Laurier was caught between these views. He received a message from the Colonial Office thanking Canada for an "offer" of 250 men, which he hadn't made. Also, a military newspaper published details of a plan to send 1,200 men.

Under pressure, Laurier announced on October 14 that Canada would raise an all-volunteer force for South Africa. Once there, they would be under British command and paid by Britain. Laurier made this decision without a vote in Parliament to avoid splitting his party. On October 30, 1,061 volunteers left Quebec City for South Africa.

At their first battle, the Battle of Paardeberg, the Canadians fought well. When the Transvaal General Piet Cronjé surrendered, British and Canadian newspapers gave credit to the Canadians. This greatly boosted Canadian confidence. Laurier then agreed to send more volunteers, and a wealthy man named Lord Strathcona even raised his own regiment, Strathcona's Horse, in western Canada.

Newspapers often showed the Boer War as a series of Canadian victories, ignoring problems like faulty equipment. British officers sometimes complained that Canadian officers were inexperienced or chosen for political reasons. After the war, Lord Dundonald, the British officer commanding the militia, suggested a "skeleton army" of well-trained officers to lead the militia if it ever needed to mobilize again. His ideas were mostly adopted, but he was dismissed in 1904 for getting involved in Canadian politics.

A new Militia Act in 1904 made Canadian officers equal to British officers and removed the Governor-General from commanding the militia. Colonel Otter became the first Canadian chief of staff for the militia. To fix problems seen in the Boer War, a veteran named Eugène Fiset pushed for improvements to the militia's medical corps. On July 1, 1905, the last British garrisons left Canada, and the militia took over defending naval bases at Halifax and Esquimalt.

Preparing for World War I

Sir Samuel Hughes became the Minister of Defence and Militia in 1911. He greatly influenced Canadian defence policy. Hughes increased military spending from $7 million in 1911 to $11 million in 1914. He was openly against the Permanent Force, preferring the militia. He even gave free cars to militia colonels and took expensive trips to observe military exercises in Europe. Hughes wanted military service to be compulsory.

Based on his Boer War experience, Hughes believed Canadian soldiers were better than British ones. Because of him, Canadians fought together as a separate force in the First World War. In August 1914, Hughes ignored existing mobilization plans and created a new organization called the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF). This force had numbered battalions that were not connected to the old militia regiments. Hughes insisted that Canadian divisions be commanded by Canadian generals. He reluctantly accepted a British officer, Lieutenant-General Edwin Alderson, to command the 1st Canadian Division only because there wasn't a qualified Canadian officer. Alderson found Hughes difficult to work with, as the defence minister interfered in many matters and insisted on using Canadian-made equipment, even if it wasn't practical.

Expansion and the World Wars (1901–1945)

After Canadians fought in the Second Boer War, it became clear that Canada needed its own support organizations. Canada quickly formed its own Engineer Corps, Medical Corps, Veterinary Corps, Signalling Corps, Ordnance Stores Corps, and Army Service Corps. During the First World War, a Provost Corps (military police) was also created. Canada was the first country to create a dedicated Army Dental Corps.

First World War

Canada's involvement in the First World War started unusually. All existing mobilization plans were scrapped, and a new fighting force was built from scratch.

In 1914, the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) was created when the United Kingdom asked for soldiers. The CEF was separate from the existing Permanent Active Militia (also called the Permanent Force) and the Non-Permanent Active Militia. The old militia regiments were not mobilized directly. Instead, their soldiers were transferred to the CEF for service overseas. The CEF was disbanded after the war ended.

| Battle | Dates | Canadian Units Involved |

|---|---|---|

| Second Battle of Ypres | April 22–May 3, 1915 | Canadian Division |

| Frezenberg Ridge | May 8–13, 1915 | Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (with British forces) |

| Festubert | May 17–25, 1915 | Canadian Division and Canadian Cavalry Brigade |

| Second Action at Givenchy | June 15–16, 1915 | Canadian Division |

| The St. Eloi Craters | March 27–April 16, 1916 | 2nd and 3rd Canadian Divisions |

| Mount Sorrel | June 2–13, 1916 | Canadian Corps |

| The Somme, 1916 | July 1–November 18, 1916 | Canadian Corps |

| Vimy Ridge | April 9–14, 1917 | Canadian Corps |

| Arleux | April 28–29, 1917 | Canadian Corps |

| Third Battle of the Scarpe | May 3–4, 1917 | Canadian Corps |

| Hill 70 | August 15–25, 1917 | Canadian Corps |

| Third Battle of Ypres | July 31–November 10, 1917 | Canadian Corps |

| Cambrai, 1917 | November 20–December 3, 1917 | Canadian Corps |

| The Somme, 1918 | March 21–April 4, 1918 | Canadian Corps |

| The Lys | April 9–19, 1918 | Canadian Corps |

| Amiens | August 8–11, 1918 | Canadian Corps |

| Second Battles of Arras, 1918 | August 26–September 3, 1918 | Canadian Corps |

| Canal du Nord | September 27–October 1, 1918 | Canadian Corps |

| St. Quentin Canal | September 29–October 2, 1918 | Canadian Corps |

| Beaurevoir Line | October 3–5, 1918 | Canadian Corps |

| Cambrai, 1918 | September 30–October 11, 1918 | Canadian Corps |

| Valenciennes | November 1–2, 1918 | Canadian Corps |

| The Sambre | November 4, 1918 | Canadian Corps |

| Pursuit to Mons | November 2–11, 1918 | Canadian Corps |

Modernizing Between the World Wars

The Otter Committee reorganized the Canadian Militia in 1920. This reorganization made sure that the traditions and histories of both the pre-war Militia and the CEF were kept alive in the modern Canadian forces. Old numbered regiments were renamed, and new military branches were created, similar to those in the British Army. These new regiments carried on the history of the wartime CEF and were allowed to adopt its battle honours.

In 1936, the Non-Permanent Active Militia created six tank battalions as part of the infantry. This was an early step towards modernizing the army. Many regiments were disbanded or combined during this time.

Second World War

The Second World War brought big changes to the Canadian Militia. On November 19, 1940, the Militia was officially renamed the Canadian Army. The full-time part became the Canadian Army (Active), and the part-time part became the Canadian Army (Reserve). Many infantry regiments were moved to the new Canadian Armoured Corps, created the same year. Horses were no longer used in the military, and the Royal Canadian Army Veterinary Corps was disbanded.

In 1939, the Canadian Active Service Force (CASF) was mobilized. Like the CEF, this force was made up of pre-war units that kept their traditional names. In 1940, Canada's land forces were renamed. The CASF became the Canadian Army (Overseas). The Permanent Force became the Canadian Army (Active), and the NPAM became the Canadian Army (Reserve). The Canadian Army (Overseas) stopped existing after the war. A new Canadian Armoured Corps was formed, and many infantry regiments were trained to fight in tanks. In Canada, Atlantic Command and Pacific Command were created to manage home defence.

There was a desire to have a full French-Canadian Brigade, but there weren't enough French-speaking staff officers. The original plan grouped infantry battalions by region. For example, the 1st Brigade was from Ontario. Later, units were mixed more. While French Canada had four French-speaking infantry battalions overseas, and the Canadian Army tried to produce training materials in French, French and English soldiers didn't have equal career chances until after the military was unified.

The 6th, 7th, and 8th Canadian Divisions were for home defence. They included many soldiers conscripted under the National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA), who legally couldn't serve "overseas." One brigade did go to the Aleutian Islands in 1943 to fight the Japanese, as it was considered North American soil, but they didn't encounter the enemy. In November 1944, some soldiers in Terrace, British Columbia, mutinied when they heard the government decided to send conscripts overseas. This "Terrace Mutiny" was the largest uprising in Canadian military history.

Irregular forces became common in western Canada during the Second World War. The Pacific Coast Militia Rangers were formed in 1942. They were disbanded after 1945 but inspired the modern Canadian Rangers.

Veterans Guard of Canada

The Veterans Guard of Canada was formed early in the Second World War. It was a defence force in case Canada was attacked. It was mostly made up of First World War veterans. At its peak, it had 37 active and reserve companies with over 10,000 soldiers. More than 17,000 veterans served in this force during the war. Active companies served full-time in Canada and overseas. The Veterans Guard also guarded internment camps, which freed younger Canadians to fight overseas. The Guards were disbanded in 1947.

| Battle/Campaign | Dates | Canadian Units Involved |

|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong | December 7–26, 1941 | Winnipeg Grenadiers and Royal Rifles of Canada |

| Raid on Dieppe | August 19, 1942 | 2nd Canadian Infantry Division |

| Sicily | July 10–August 6, 1943 | I Canadian Corps |

| Advance from Reggio di Calabria to Campobasso | September 3–October 14, 1943 | I Canadian Corps |

| Battles of the Winter Line (Sangro, The Gully and Ortona) | December 1943–April 1944 | I Canadian Corps |

| Liri Valley | May–June 1944 | I Canadian Corps |

| Gothic Line | July 1944 | I Canadian Corps |

| Advance through the Lombard Plain | August 1944–February 1945 | I Canadian Corps |

| Normandy | June 6–July 1944 | First Canadian Army and the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion |

| Falaise Gap | First Canadian Army | |

| Clearing the Channel Coast | September 1944 | First Canadian Army |

| The Scheldt | September 1944–February 1945 | First Canadian Army |

| Rhineland | February–March 1945 | First Canadian Army |

| Securing the Netherlands | March–May 1945 | First Canadian Army |

Early Cold War (1946–1968)

After the Second World War, the Canadian Army changed a lot. The full-time part became the Canadian Army Active Force, and the part-time part became the Canadian Army Reserve Force.

Before 1930, the Canadian Army was small, made up of professional soldiers and volunteers. It followed British Army traditions. After 1945, Canada started to become more independent from Britain, including in its military. There was a debate about making the army more professional. Some wanted highly educated officers who could work with politicians. Others wanted to keep old traditions and have leaders from certain social classes. This disagreement made it hard to develop modern management for the army.

Korean War

In the summer of 1950, Canada was asked to send troops to the Korean War. The government realized its Mobile Strike Force was too small. To avoid conscription (forcing people to join the military), the Defence Minister, Brooke Claxton, promised to raise an all-volunteer Army Special Force for Korea. By the fall of 1950, over 10,000 men had volunteered. Canada sent nearly 27,000 Canadians to serve in the Korean War. About 1,500 became casualties, with 516 deaths, mostly from combat.

Canada's involvement included naval ships and aircraft, plus the 25th Canadian Infantry Brigade. This brigade was part of the 1st Commonwealth Division. In late 1950, the Princess Patricia's Regiment went to South Korea. In February 1951, they joined an Anglo-Australian brigade. During the Battle of Kapyong (April 22–25, 1951), the Princess Patricia's Regiment fought bravely. A Chinese attack caused a South Korean division to collapse. The Princess Patricia's Regiment, along with British, Australian, and New Zealand units, held the line. At one point, they had to call for artillery fire on their own positions to stop the Chinese. Their successful defence earned them a special award from U.S. President Truman, the first time a Canadian unit received such an honour.

The rest of the 25th Infantry Brigade arrived in South Korea in May 1951. Canada's military grew stronger because of the Korean War. A plan to switch to U.S.-designed weapons was put on hold, and Canada used its Second World War–era British weapons instead. In 1951, the Defence Minister announced a large military budget to raise an infantry division and send a brigade to Europe. This was because it was believed that the Soviet Union might invade West Germany. Canada decided to increase its forces for West Germany's defence.

There was a disagreement between General Charles Foulkes and General Guy Simonds about whether Canadian troops would serve under U.S. or British command in Europe. Simonds argued that Canadians should serve with the British Army in northern Germany, partly due to historical reasons and doubts about the U.S. Army's combat readiness. In the late 1950s, Canada used a mix of European, British, and U.S. weapons instead of fully switching to American ones.

After Korea

After the Korean War, there were few major missions until peacekeeping became common in the 1960s.

Before the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, the Canadian Army was the only Commonwealth nation to provide the King's Guard in London. In June 1953, Canadian troops served as the guard, along with Australian soldiers.

In the early 1950s, the Army advertised in British newspapers for former British soldiers to join the Canadian Army. These recruits were brought to Canada for training. After six months, their families could move to Canada to join them.

The late 1950s saw a big increase in the Army's size. Canada created its largest standing army ever, largely due to General G. G. Simonds. This expansion was needed to keep a presence in Germany for NATO and to provide forces for the Korean War. Simonds believed that if a third world war started in Europe, Canadian soldiers needed to be there already. From 1950 to 1953, the Canadian military grew from 47,000 to 104,000 people.

Simonds believed in esprit de corps (team spirit) to motivate soldiers. He wanted to build on the Canadian Army's history and traditions to make soldiers proud of their regiments. This is why he moved militia regiments like the Black Watch and the Queen's Own Rifles into the regular army. He also created the Regiment of Canadian Guards, similar to the British Brigade of Guards, with red uniforms and bearskin hats. By 1953, the defence budget was ten times higher than in 1947. Unlike after other wars, military spending stayed high after the Korean War. The 1950s and 1960s are seen as a "golden age" for the military because it wasn't constantly underfunded.

The Canadian Army was the only service that made some allowances for French-Canadians. In 1952, the Collège Militaire Royal de Saint-Jean opened to train French-Canadian officers in French. However, the Army was still mostly English-speaking in the 1950s. The Royal 22e Régiment and the 8th Hussars were the only regular army regiments for French-Canadians.

In the early 1950s, Canada sent a brigade to West Germany as part of its NATO commitment. This brigade later became 4 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group and stayed in Germany until the 1990s.

The future of the Army became uncertain in the age of nuclear weapons. The post-war Militia (part-time army) changed its role from combat to civil defence. In 1968, The Canadian Airborne Regiment, a full-time parachute regiment, was created.

Unifying the Canadian Forces

Paul Hellyer, the Liberal Defence Minister, proposed uniting the Army, Air Force, and Navy into one service in 1964. He argued that having separate services for land, sea, and air was old-fashioned. Hellyer's plan faced strong opposition. General Simonds called his ideas "nonsense." He argued that different environments of war needed different leadership styles.

Hellyer's Chief of the Defence Staff, Air Chief Marshal Frank Robert Miller, resigned in protest. Other generals and admirals also resigned. However, most Canadians didn't care much about Hellyer's plans. Newspapers often made fun of the officers who resigned, showing them as old-fashioned. Hellyer was seen as a bold leader. He wanted to be prime minister and used unification to show he was innovative.

Despite strong opposition from Conservative Members of Parliament, Parliament passed Hellyer's Canadian Forces Reorganization Bill on April 25, 1967. On July 1, 1967, to celebrate Canada's 100th birthday, a huge military display was held in Ottawa. All three services marched together. Many participants felt it was the end of their separate traditions. The Army was combined with the Royal Canadian Navy and the Royal Canadian Air Force on February 1, 1968. This was called Unification. The new Canadian Forces was the first combined military force in the modern world. The Army became known as Mobile Command.

Most of the old military branches were disbanded and merged with their Navy and Air Force counterparts. Many people, especially veterans and serving members, strongly opposed unification. They felt it was a mistake for the Canadian Forces. One of the most controversial parts was Hellyer's decision to get rid of the traditional British-style uniforms for the Army, Navy, and Air Force. He replaced them with a common green American-style uniform. He also changed traditional British-style ranks to American-style ranks. On August 16, 2011, the Canadian Government brought back the names Royal Canadian Navy, Canadian Army, and Royal Canadian Air Force, but the unified structure of the Canadian Forces remained.

- Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps and Royal Canadian Dental Corps became the Canadian Forces Medical Service and Canadian Forces Dental Service.

- Royal Canadian Corps of Signals became the Communications and Electronics Branch. In 2013, the army part got its old name back.

- Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps merged with supply and transport services to become the Logistics Branch.

- Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers became the Electrical and Mechanical Engineering Branch. In 2013, it also got its old name back.

- Clerical parts of the Army Service Corps, Pay Corps, and Postal Corps became the Administration Branch (later merged with Logistics).

- Canadian Provost Corps (military police) and Canadian Intelligence Corps became the Security Branch. In 1982, they split into the Security Branch and Intelligence Branch. In 2017, Army Intelligence Officers became part of the Canadian Intelligence Corps again.

Post-Unification and the Late Cold War (1969–1991)

In 1968, the new Liberal Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau, wanted to re-evaluate Canada's defence commitments. For a while, he considered leaving NATO. But he decided to stay to keep good relations with the United States and European countries. On April 3, 1969, Trudeau announced the new priorities for the Canadian Forces:

- 1. Protecting Canada from outside and inside threats.

- 2. Working with the United States to defend North America.

- 3. Defending Western Europe as part of NATO.

- 4. United Nations peacekeeping missions.

In May 1969, Defence Minister Léo Cadieux told European leaders that Canada would greatly cut its NATO commitments. On June 23, 1969, Cadieux announced big cuts in defence spending. In September 1969, it was announced that half of Canadian forces in West Germany would be pulled out. The rest moved to Lahr in southern West Germany to work under American command. This ended the historical links between the British and Canadian armies.

The main operation for the Canadian Forces in 1969 was in Canada. The Montreal police went on strike, leading to riots that the Army had to put down. In 1970, the new Defence Minister, Donald Stovel Macdonald, said that protecting Canada's independence and helping with Canada's social and economic development were the main goals of the Canadian Forces. A 1970 report, Defence in the Seventies, stated that the top priority for the Canadian Forces was now internal security, with the future enemy seen as the FLQ (Front de libération du Québec) instead of the Soviet Union.

The Regular Force was made smaller in 1970. The number of regular infantry battalions was cut from 13 to 10. This meant some regiments were reduced or their soldiers were moved to other regiments.

In October 1970, during the October Crisis, the army was called in to help civil authorities. The Royal 22e Régiment was sent to guard government buildings in Montreal. This deployment was not popular with senior military leaders. They feared, correctly, that Trudeau would use the crisis to justify his "Priority One" of internal security. Throughout the 1970s, the Canadian Forces "stagnated" due to budget cuts. This reduced both the size of the forces and the amount of equipment available.

In 1976, the Trudeau government bought 128 German Leopard tanks for Mobile Command. These tanks were already outdated compared to Soviet tanks, but they were considered useful for "Priority One." Also, 400 Swiss-built armoured vehicles were bought and stationed across the country. These were meant for "Priority One" (putting down riots), though their purpose was described as "peacekeeping." By the end of the 1970s, Mobile Command had become an internal security force, not capable of fighting a major conventional war.

The frequent changes in defence ministers in the 1970s meant no minister truly understood their job. This led to confusion and a lack of direction. Trudeau also brought in civil servants and "management experts" to try and "rationalize" military decision-making. However, these efforts led to several expensive problems with military equipment purchases.

French-Speaking Units

In 1967, a Royal Commission criticized the Canadian military for mostly operating in English. It demanded more opportunities for French-Canadians. The commission said the Army was limiting French-Canadians to the Royal 22e Régiment and a few other units in Quebec. It stated that French-Canadians who wanted to reach high command had to serve in "unfamiliar and sometimes unwelcoming surroundings outside Quebec." Because the Army outside the Royal 22e Régiment was not seen as friendly to French-Canadians, very few enlisted.

The Royal Commission demanded more French-Canadian units outside Quebec. It also said that all high-ranking officers should be fluent in both English and French. It also stated that 28% of new recruits should be French-Canadian. All these recommendations became law. One result was that French-Canadian officers often had an advantage in getting high command positions because most were fluent in English, while most English-Canadian officers were not fluent in French.

In the late 1960s, the Canadian Forces started creating French Language Units (FLUs) and encouraging career opportunities for French-speakers. Defence Minister Léo Cadieux announced their creation on April 2, 1968. These included artillery and armoured regiments, with two battalions of the Royal 22e Régiment at their core. The Army FLUs eventually gathered at Valcartier and became known as 5e Groupement de combat. A French-speaking regular armoured regiment, 12e Régiment blindé du Canada, and an artillery regiment, 5e Régiment d'artillerie légère du Canada, were created. A "Francotrain" program was set up to teach English-Canadian officers French and train French-Canadian recruits in special skills. By the 1990s, the Canadian Forces became a successful example of a truly bilingual institution in Canada.

Mobile Command focused on peacekeeping missions and future conventional war in Europe. Equipment like the M113 APC (armoured personnel carrier) and Leopard tank modernized the army. The Cougar and Grizzly AVGP (armoured vehicles) were used for scouting and mechanized infantry.

The 1980s

In 1984, the Progressive Conservative government under Brian Mulroney promised to fix the neglect of the Trudeau years. However, the government struggled between increasing the military budget, giving contracts to supporters, and balancing the budget. Mulroney continued the trend of frequently changing defence ministers, often appointing weaker ones.

In 1985, the Mulroney government brought back different uniforms for the Canadian Forces. Mobile Command was allowed to wear tan brown uniforms to distinguish them from the Navy and Air Force. This was popular with soldiers. After the first defence minister resigned, Erik Nielsen, a Second World War veteran, became the new defence minister. He was a strong supporter of the Canadian Forces and managed to increase the military budget. The Canadian brigade in West Germany, which had been under-strength since 1969, was finally brought to full strength.

In 1985, the United States sent an icebreaker through the Northwest Passage without Canada's permission. This made Ottawa realize the need to protect Canada's claims to Arctic sovereignty. A military exercise in 1986 showed that Canada could not quickly move a military force to Norway, or by extension, the Arctic.

In 1987, the new Defence Minister, Perrin Beatty, proposed a major increase in the military budget. The Army would have three divisions: two for NATO in central Europe and one for Canada's defence. The plan also included buying nuclear submarines for Arctic sovereignty, but this idea faced so much opposition that it was dropped. The end of the Cold War in 1989–90 also led to new military cuts.

Towards the end of the Cold War, the Canadian Land Forces started emphasizing a "Total Force" concept. This aimed for greater integration between Regular Force and Reserve Force soldiers. Unsuccessful experiments included "10/90 battalions," which were meant to be 10% Regular Force and 90% Reserve Force. These organizations were later undone.

Successful changes included reorganizing regional headquarters into larger "total force" headquarters. In September 1991, the five regional Militia Areas were reorganized into four Land Force Areas. Regular Force units were integrated into this command structure based on their location.

New Challenges in the Post-Cold War Era (1990–Present)

Many expected major defence cuts after the Cold War. However, the failure of the Meech Lake Accord in June 1990 led to a big increase in support for Quebec separatism. For a time, Canada seemed close to breaking up. In this situation, the military was seen as a last resort to prevent a possible civil war. The Oka Crisis also added to the sense of crisis in 1990.

The Oka crisis began on July 11, 1990, with a shootout in Oka between the Mohawk Warrior Society and the Quebec police, which left one officer dead. The armed Warrior Society occupied land they claimed belonged to the Mohawk people in Oka. They also occupied the Mercier bridge, which links Montreal to the mainland. On August 17, 1990, Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa asked the Army to step in to keep "public safety." Prime Minister Mulroney approved, and General John de Chastelain ordered the 5e Groupe Brigade Mecanisee du Canada from Valcartier to Oka and Montreal. On August 26, 1990, soldiers removed the Mohawk Warriors from the Mercier bridge without bloodshed. After a month-long standoff at Oka, the Mohawk Warriors ended the confrontation on September 26, 1990.

The French-Canadian soldiers of the Royal 22e Régiment were praised for their discipline during the Oka crisis. This was unusual in Quebec, which was generally against the military. One result of the 1990 crises was that post-Cold War cuts were not as severe as expected. In September 1991, the defence minister announced that Canadian Forces bases in Germany would close by 1995, and the military would lose only 10% of its personnel. In fact, the bases in Germany closed on July 30, 1993, two years early.

Mobile Command took part in several international missions after the fall of Communism. Besides a small role in the Gulf War in 1991, Canadian Forces were heavily involved in UN and NATO missions in the former Yugoslavia. These missions tested the shrinking military's abilities.

In 1995, the Canadian Airborne Regiment was disbanded after the Somalia Affair. This event also led to other changes in the military, such as mandatory sensitivity training for all members.

Other decisions in the 1990s reflected changing social values in Canada. Women in Highland regiments were allowed to wear the kilt. Indigenous people were allowed to grow long hair in traditional braids, and the turban was accepted for Sikhs.

In 1998, Mobile Command was renamed Land Force Command. On August 15, 2011, Land Force Command was renamed the Canadian Army.

Joint Task Force 2 was created to take over counter-terrorism duties from the RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police). Canada participated in the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. During this time, emergency equipment was bought, including modern artillery and armoured patrol vehicles. In 2006, a new Canadian Special Operations Regiment was created as part of a major reorganization. Special operations units are now under Canadian Special Operations Command.

In January 1999, Toronto received too much snow, and Mayor Mel Lastman "called in the cavalry." The Army had helped with natural disasters before, like sandbagging during floods in Winnipeg and cleaning up after ice storms in Operation Recuperation. More recently, in 2019, the Army helped with floods in New Brunswick.

In April 2020, the Army provided rescue services to help senior citizens in Long-Term Care Facilities in Ontario and Quebec during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada as part of Operation LASER.

Women in the Canadian Army

The Canadian Women's Army Corps was created in the Second World War as a separate part of the Army. It remained separate until the 1960s, when women were integrated into the Canadian Forces. Women were initially limited to certain jobs, but by the 1990s, they were accepted into all military trades. Captain Nichola Goddard was the first female combat soldier killed in battle when she died in Afghanistan in 2006.

The first "lady cadets" graduated from the Royal Military College of Canada in the 1980s.

Canadian Army Flags

To help distinguish its soldiers from British forces, the flag of the Canadian Active Service Force, also known as the Battle Flag of Canada, was approved on December 7, 1939. This was the Army's command flag. However, the flag was not popular, and its use stopped on January 22, 1944. After the Second World War, the Canadian Army did not have its own special command flag. It just used the Canadian National Flag when needed. In 1989, Mobile Command asked for and received a command flag. It was designed with the Canadian flag in the corner and the army badge in the main part.

The Union Jack (British flag) was also used as the Army's service flag, flown at various army bases, along with the Red Ensign until 1965. After 1965, the current Canadian Flag was used exclusively.

Service Flags

Canadian Army Command Flags

Leadership

The Commander of the Canadian Army is the main leader of the Canadian Army. This position was called General Officer Commanding the Forces (Canada) from 1875 to 1904. Then it was called Chief of the General Staff from 1904 until 1964, when the position was removed during the unification of Canada's military. It was titled Commander of Mobile Command from 1965 to 1993 and Chief of the Land Staff from 1993 to 2011. In 2011, Land Force Command was renamed the Canadian Army, and the position was renamed to its current title.

Images for kids

-

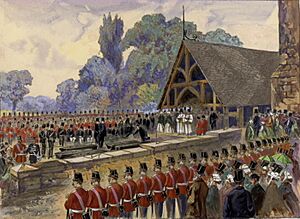

The Battle of Chateauguay during the War of 1812. In the battle, locally raised fencibles, militia, and Mohawk warriors, repulsed an American assault for Montreal.

See also

- Bibliography of Canadian military history

- Military history of Canada

- Canadian Militia

- Royal Military College of Canada

- Supplementary Order of Battle

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |