History of trade and industry in Birmingham facts for kids

Birmingham started as a small, quiet farming village in England. Over time, it grew into a busy market town and then a major city, known for its amazing industries and clever people. Let's explore how this transformation happened, starting way back in the Middle Ages!

Contents

Early Beginnings: The 11th Century

Birmingham first appears in a very old book called the Domesday Book. This book was like a big survey of England, made in 1086 by William the Conqueror. Back then, Birmingham was just a small farming area, not a big town at all. It was part of a larger estate owned by a powerful lord. Some people later claimed that Birmingham had a market even before the Norman conquest in 1066, but there isn't clear proof from that time.

A Market Town is Born: The 12th Century

A big change for Birmingham happened in 1166. A local lord named Peter de Birmingham bought a special permission, called a royal charter, from King Henry II. This charter allowed him to hold a weekly market in Birmingham and charge fees for people to sell their goods there. This was a huge deal!

With this new charter, Peter de Birmingham started to plan a proper market town.

- He created the triangular marketplace that we now know as the Birmingham Bull Ring.

- He sold special plots of land around the market. People who bought these plots got privileges, like being able to sell goods without paying extra fees.

- He changed local trade routes so they would pass through the new market.

- He rebuilt the Birmingham Manor House using stone.

- The first church, St Martin in the Bull Ring, was probably built around this time too.

Just 23 years later, Peter's son, William de Birmingham, asked King Richard I to confirm the market's status. By then, the market wasn't just at a castle; it was in "the town of Birmingham." This shows how quickly the area was growing!

During this time, Birmingham's main jobs were making textiles (like cloth), working with leather, and making things from iron. People also made pottery, tiles, and items from bone and horn. Small factories, called Kilns, made special local pottery called Deritend Ware.

Growing Industries: The 13th Century

The first records of specific craftsmen in Birmingham appeared in 1232. These records mentioned a smith, a tailor, and four weavers. The market helped these businesses a lot. It provided raw materials like hides and wool, and there were always customers, both from the town and from the countryside.

Around this time, records also mention mercers (who sold fabrics) and purveyors (who supplied goods). There were tanning pits in use, where animal skins were turned into leather. People also used hemp and flax to make rope, canvas, and linen. By 1296, there were at least four forges (places where metal is heated and shaped) in the town.

Birmingham was also an important stop on major trade routes. By the end of the 13th century, it was a key place for moving cattle from Wales to other parts of England, like Coventry and the South East.

Specialised Skills: The 14th Century

The land around Birmingham was better for raising animals than for growing crops. So, cattle were the most common livestock, along with some sheep. As the town grew, its trade became more varied, and a class of merchants (traders) emerged.

Even though most goods made in Birmingham were for local use, the town was already becoming known for jewellery. In 1308, an important inventory listed "twenty two Birmingham Pieces." These were small, valuable items, possibly jewellery or metal decorations, that were famous enough to be known even in London.

By 1332, Birmingham had a similar number of craftsmen to other industrial towns in Warwickshire. Birmingham became a major center for the wool trade. Birmingham merchants even represented Warwickshire at important meetings about wool in York and Westminster. Some Birmingham merchants were trading large amounts of wool with other countries in continental Europe.

In 1343, some Birmingham men were caught selling fake silver items. This shows that there were already goldsmiths (people who work with gold) in the town. Records from 1384 and 1460 also mention goldsmiths, a trade that needed more than just local customers to survive.

Other jobs included wikt:Skinners (who worked with animal skins), tanners, and wikt:saddlers (who made saddles). Evidence of slag and hearth bloom (waste products from metalworking) shows that iron working was also happening early on.

By 1379, there were at least four smiths in Birmingham, with more appearing in the next century. While there were many weavers and dyers, much of the cloth sold in Birmingham's market actually came from nearby villages. However, the textile industry in Birmingham was one of the first to use machines. By the end of the 14th century, nearly a dozen fulling mills (which cleaned and thickened cloth) existed in the Birmingham area. Many of these were old corn mills that had been changed, but one was built specifically for fulling cloth in 1358.

In 1397, records show that Birmingham sold 44 broadcloths. This was a small amount compared to the 3,000 sold in the big textile center of Coventry, but it made up almost a third of all the textile trade in the rest of Warwickshire.

Continued Growth: The 15th Century

In 1403, a legal case showed that traders from Birmingham were dealing in iron, linen, wool, brass, and even "calibe" (possibly fur), as well as cattle. This shows how varied Birmingham's trade had become.

A New Era: The 16th Century

One of Birmingham's first famous writers was John Rogers. He helped create and edit the 1537 Matthew Bible. This was the first complete and approved English Bible ever printed, and it was very important, forming the basis for later Bibles like the Authorized King James Version. Rogers also translated another book in 1548, which was the first book by a Birmingham man known to be printed in England.

By the early 1500s, Birmingham was already a center for metalworking. For example, in 1523, when King Henry VIII planned to invade Scotland, Birmingham's smiths made huge orders of arrowheads for his army.

In 1538, a churchman named John Leland visited the Midlands and wrote about Birmingham. He described it as a "Good Markett Towne" with many smiths who made knives, cutting tools, and bits for horses. He also mentioned many "Naylors" (nail makers). He noted that the smiths got their iron and coal from nearby Staffordshire.

In 1547, a report mentioned that the Guild of the Holy Cross was in charge of "keeping the Clocke and the Chyme" at St Martin's Church. This cost them a small amount of money each year. The next time a clock is mentioned is in 1613. A survey in 1553 named one of Birmingham's first goldsmiths, Roger Pemberton.

During this century, some of Birmingham's main medieval groups and institutions disappeared. The Priory of St Thomas (a religious house) was closed in 1536. The Guild of the Holy Cross and other guilds were also disbanded in 1547. Most importantly, the de Birmingham family lost control of the manor of Birmingham in 1536, possibly due to a fight between Edward de Birmingham and John Sutton. After being owned by the King and then another powerful duke, the manor was sold in 1555 to Thomas Marrow.

From then on, Birmingham never had a resident Lord of the Manor again. This meant the townspeople had a lot more freedom to run their own affairs and businesses. This freedom was a very important reason why Birmingham grew so much in the centuries that followed!

Innovation and Conflict: The 17th Century

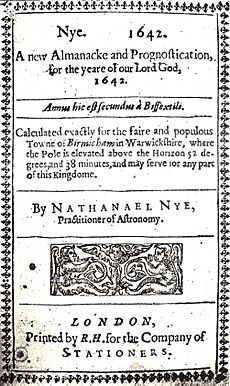

In 1642, a clever mathematician and astronomer from Birmingham named Nathaniel Nye published a book called A New Almanacke and Prognostication. This book was a kind of calendar and forecast, specifically calculated for Birmingham.

During the English Civil War (a big war in England), Birmingham's smiths were very important. They made over 15,000 sword blades, which they supplied only to the Parliamentarian army. Nathaniel Nye, the same clever man, was recorded testing a Birmingham cannon in 1643. He also experimented with a saker (a type of cannon) in 1645. From 1645, he became the master gunner for the Parliamentarian army at Evesham. In 1646, he successfully led the artillery at the Siege of Worcester. He wrote about his experiences in his 1647 book The Art of Gunnery, believing that war was a science as much as an art.

The first known clockmakers in Birmingham arrived from London in 1667. Between 1770 and 1870, there were more than 700 clock and watch makers in Birmingham!

In 1689, a local lord named Sir Richard Newdigate asked Birmingham manufacturers if they could supply the British Government with small arms (like guns). He stressed that the weapons needed to be as good as those imported from other countries. After a successful test order in 1692, the Government placed its first big contract. On January 5, 1693, five local gun makers were chosen to produce 200 "snaphance musquets" each month for a year. They were paid 17 shillings per musket, plus extra for delivery to London. This marked the beginning of Birmingham's long history as a major center for gun manufacturing.

|

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |