History of Birmingham facts for kids

Birmingham has grown for about 1400 years. It started as a small village in the 7th century, during the Anglo-Saxon period. This village was on the edge of the Forest of Arden in early Mercia. Over time, it became a major city. People moving in, new ideas, and local pride helped create big social and economic changes. This led to the Industrial Revolution, which inspired other cities around the world to grow.

In the last 200 years, Birmingham changed from a market town to the fastest-growing city of the 19th century. This happened because of money invested by the city, scientific discoveries, new business ideas, and many workers moving to its suburbs. By the 20th century, Birmingham was the main center for manufacturing and car making in the United Kingdom. It was known first as a city of canals, then of cars, and more recently as a top place for conventions and shopping in Europe.

At the start of the 21st century, Birmingham was at the heart of a large modern city area. It had important places for education, manufacturing, shopping, sports, and conferences.

Contents

- Ancient Times

- Roman Times (around 47 AD to 600 AD)

- Anglo-Saxon and Norman Birmingham (around 600 AD to 1166 AD)

- The Medieval Market Town (1166–1485)

- Tudor and Stuart Birmingham (1485–1680)

- The Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution (1680–1791)

- Victorian Birmingham (1832–1914)

- Wartime and Between Wars (1914–1945)

- Post-War Birmingham (1945–1975)

- Modern Birmingham (1975–Present)

- Historic Population

- Images for kids

Ancient Times

Stone Age Discoveries

The oldest human item found in Birmingham is the Saltley Handaxe. This stone axe is about 500,000 years old and was found in 1892. It was discovered in the gravels of the River Rea in Saltley. This axe was the first proof that early humans lived in the English Midlands. Before this, people thought this area was empty before the last ice age ended. Similar axes have also been found in Erdington and Edgbaston. Evidence from digging in Quinton, Nechells, and Washwood Heath suggests that the climate and plants in Birmingham during that time were like today.

The area became too cold to live in when the last ice age began. The next signs of human life in Birmingham are from the mesolithic period. In 2009, a 10,400-year-old settlement was found in Digbeth. This showed that hunter-gatherers used basic flint tools and cleared forests by burning. Flint tools from later in the Mesolithic period (8,000 to 6,000 years ago) have been found near streams. These likely belonged to hunting groups or people camping overnight.

The oldest human-made structures in the city are from the Neolithic era. These include a possible ancient path seen from the air near Mere Green. There is also a surviving burial mound (barrow) at Kingstanding. Neolithic axes found in Birmingham were made from stone from places like Cumbria, Leicestershire, North Wales, and Cornwall. This shows that the area had many trade connections back then.

Bronze and Iron Ages

Stone axes used by the first farmers over 5,000 years ago have been found in the city. The first bronze axes date back about 4,000 years. Pottery from 2700 BC has been found in Bournville.

The most common ancient sites in Birmingham are burnt mounds. These are piles of heated stones, possibly used for cooking or steam baths. About 40 to 50 of these have been found in the Birmingham area. Most date from 1700–1000 BC. Sites like the one in Bournville also show signs of larger settlements, with cleared woodlands and grazing animals. Possible Bronze Age settlements with later Iron Age farms have been found at Langley Mill Farm in Sutton Coldfield. More evidence of Iron Age settlement was found at Berry Mound, a hill fort near Shirley.

Roman Times (around 47 AD to 600 AD)

During Roman times, a large military fort called Metchley Fort was built in Edgbaston, near where the Queen Elizabeth Hospital is today. This fort was built soon after the Romans invaded Britain in 43 AD. It was used, then left, then used again, and finally abandoned around 120 AD. Remains of a civilian settlement, called a vicus, were also found next to the fort. Digs at Parson's Hill in Kings Norton and Mere Green have found Roman kilns.

Even though no direct proof has been found, the name Witton comes from an Old English word meaning "settlement." This suggests it might have been a Roman-British village. It would have been close to where Icknield Street crossed the River Tame at Perry Barr.

Roman military roads met in the Birmingham area. These roads came from places like Letocetum (near Lichfield) in the north, Salinae (Droitwich Spa) in the southeast, Alauna (Alcester) in the south, and Pennocrucium (Penkridge) in the northwest. Parts of these roads are now lost under the city. However, a section of the road from Wall is still well-preserved in Sutton Park. Other Roman settlements like Castle Bromwich and Grimstock Hill also had roads leading to them. The Roman routes from Wall and Alcester were later called Icknield Street in the Middle Ages.

Anglo-Saxon and Norman Birmingham (around 600 AD to 1166 AD)

How Birmingham Began

There isn't much archaeological evidence from the Anglo-Saxon era in Birmingham. Written records are also few, with only seven old Anglo-Saxon documents mentioning areas like King's Norton, Yardley, Duddeston, and Rednal. However, the names of places suggest that many settlements that later became part of the city, including Birmingham itself, were founded during this time.

The name "Birmingham" comes from "Beormingahām" in Old English. This means the home or settlement of the Beormingas, a tribe or clan. Their name means "Beorma's people." Beorma might have been their leader, an ancestor, or a mythical figure. Place names ending in -ingahām usually mean they were early settlements. This suggests Birmingham probably existed by the early 7th century. Nearby settlements with names ending in -tūn (farm), -lēah (woodland clearing), -worð (enclosure), and -field (open ground) were likely built later as the Anglo-Saxon population grew.

Anglo-Saxon Settlements

We don't know the exact location of Anglo-Saxon Birmingham. People used to think it was a village around the River Rea crossing at Deritend, with a village green where the Bull Ring is now. But no Anglo-Saxon items were found during big digs before the Bull Ring was rebuilt in 2000. Other places have been suggested, like the Broad Street area or Hockley. It's also possible that early Birmingham was just scattered farms without a central village. The name might have even referred to a larger area belonging to the Beormingas tribe.

During the early Anglo-Saxon period, the area of modern Birmingham was a border between two groups. Birmingham and the areas to the north were likely settled by the Tomsaete, or "Tame-dwellers." These were Anglian tribes who came from the Humber Estuary and later formed the kingdom of Mercia. Areas in the south, like Northfield and King's Norton, were settled later by the Hwicce, a Saxon tribe. The exact border between these groups might be shown by the later church areas of Lichfield and Worcester.

In the late 7th century, the kingdom of Mercia grew and took over the Hwicce. It eventually ruled most of England. But in the late 9th century, Viking power grew, and eastern Mercia fell under their control (the Danelaw). The western part, including Birmingham, was then ruled by Wessex. In the 10th century, Edward the Elder of Wessex reorganized western Mercia for defense. He created shires around fortified towns called burhs. Birmingham became a border area again. The parish of Birmingham was part of Warwickshire, but other parts of the modern city were in Staffordshire and Worcestershire.

Birmingham in the Domesday Book

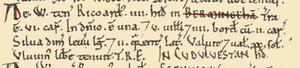

The first written record of Birmingham is in the Domesday Book from 1086. It was listed as a small manor called Bermingeham, worth only 20 shillings.

The Domesday Book says: "From William, Richard holds four hides in Birmingham. There is land for six ploughs, in the demesne, one. There are five villagers and four smallholders with two ploughs. The woodland is half a league long and two furlongs wide. The value was and is twenty shillings. Wulfwin held it freely in the time of King Edward."

At that time, Birmingham was much smaller than other villages nearby, like Aston. Other manors mentioned in the Domesday survey included Sutton, Erdington, Edgbaston, Selly, Northfield, Tessall, and Rednal. A settlement called "Machitone" was also mentioned, which later became Sheldon.

The Manor of Birmingham was at the bottom of the eastern side of the Keuper Sandstone ridge. In 1086, it would have been a small house. Later, it became a timber-framed house surrounded by a moat, which was filled by the River Rea.

The Medieval Market Town (1166–1485)

How the Town Grew

Birmingham began to change from a small farming area in 1166. This was when Peter de Birmingham, the local lord, bought a special paper (a royal charter) from King Henry II. This charter allowed him to hold a weekly market "at his castle at Birmingham" and to charge fees for goods sold there. This was one of the first such charters in England. Peter then created a planned market town on his land.

During this time, the triangular marketplace that became the Bull Ring was laid out. People could buy plots of land around it, which gave them special rights in the market and freedom from tolls. Local trade routes were changed to go through the new market and its crossing of the River Rea at Deritend. The Birmingham Manor House was rebuilt in stone, and the parish church of St Martin in the Bull Ring was likely first built. By the time Peter's son, William de Birmingham, asked King Richard I to confirm the market's status 23 years later, it was called "the town of Birmingham."

The new town grew quickly because economic conditions were good. Birmingham's market was the first on the Birmingham Plateau. This area saw its population double or triple between 1086 and 1348. People needed more farmland, so they cleared forests and enclosed land in places like King's Norton, Yardley, Perry Barr, and Erdington. Farmers also needed to sell more of their crops to pay rent in cash. It took almost a century before markets in Solihull, Halesowen, and Sutton Coldfield competed with Birmingham. By then, Birmingham's success was a model for others.

Within 100 years of the 1166 charter, Birmingham became a busy town of craftsmen and merchants. Kings visited Birmingham in 1189, 1235, and 1237. In 1275, two burgesses (town representatives) were asked to go to Parliament. This didn't happen again until the 19th century. But it showed Birmingham was as important as older towns like Alcester and Stratford-upon-Avon. Fifty years later, records from 1327 and 1332 show Birmingham was the third largest town in the county, after Warwick and Coventry. Coventry was then the fourth largest city in England.

Markets and Merchants

Birmingham's market likely mostly sold farm products during the medieval period. The land around Birmingham was better for raising animals than growing crops. Bones found show that cattle were the main livestock. Records from 1285 and 1306 mention stolen cattle being sold in town, suggesting a large trade. However, trade in Birmingham grew as merchants appeared. Records from the early 13th century mention cloth sellers and food suppliers. A legal case in 1403 showed traders from Wednesbury were selling iron, linen, wool, brass, and steel, as well as cattle.

By the 14th century, Birmingham was a known center for the wool trade. Two Birmingham merchants represented Warwickshire at a meeting in York in 1322 to discuss wool standards. Others went to wool merchant meetings in Westminster in the 1340s. At least one Birmingham merchant traded a lot of wool with other countries. Records from 1397 show that Birmingham sold 44 broadcloths. This was a small part of the 3,000 sold in Coventry, but almost a third of all cloth sold in the rest of Warwickshire.

Birmingham was also on several important trade routes. By the late 13th century, it was a key stop for moving cattle from Wales to Coventry and the Southeast of England. Records from 1340 show wine imported through Bristol was unloaded at Worcester and taken by cart to Birmingham and Lichfield. This route from Droitwich is on the Gough Map from the mid-14th century. It was described as one of England's "Four Great Royal Roads."

The de Birmingham family actively promoted the market. The fees from the market were a big part of their income. When a rival market started in Deritend, they bought that area by 1270. The family made sure traders from places like King's Norton and Tipton paid their tolls. In 1250, William de Birmingham got permission to hold a fair for three days around Ascensiontide. By 1400, a second fair was held at Michaelmas. In 1439, the lord arranged for the town to be free from royal suppliers.

Early Industries

Signs of small industries in Birmingham appear as early as the 12th century. The first written proof of craftsmen in the town is from 1232. A group of burgesses who wanted to be free from helping with the lord's haymaking included a smith, a tailor, and four weavers. Manufacturing likely grew because the market provided raw materials like hides and wool. It also created a demand for goods from rich merchants and visitors. By 1332, Birmingham had a similar number of craftsmen as other industrial towns in Warwickshire.

Looking at craftsmen's names in old records suggests that the main industries in medieval Birmingham were textiles, leather working, and iron working. Digs also show there was pottery, tile making, and probably working with bone and horn. By the 13th century, there were tanning pits in Edgbaston Street. Hemp and flax were used to make rope, canvas, and linen. Kilns making the special local Deritend Ware pottery existed in the 12th and 13th centuries. Skinners, tanners, and saddlers are mentioned in the 14th century. Finding slag and hearth bloom in pits suggests early iron working. Records from 1296 show at least four forges in town. Four smiths are mentioned in a 1379 tax record, and seven more in the next century.

Although 15 to 20 weavers, dyers, and fullers were in Birmingham by 1347, this wasn't much more than in nearby villages. Some cloth sold in Birmingham's market came from rural areas. However, this was the first local industry to use machines. Nearly a dozen fulling mills were in the Birmingham area by the late 14th century. Many were changed from corn mills, but one at Holford near Perry Barr was built for fulling in 1358.

Most manufactured goods were for local use. But there is some proof that Birmingham was already a special and well-known center for jewellery in the medieval period. A list of items belonging to the Master of the Knights Templar in England in 1308 included 22 Birmingham Pieces. These were small, valuable items, possibly jewellery or metal ornaments. They were well-known enough to be mentioned without explanation even in London. In 1343, three Birmingham men were punished for selling fake silver items. There are records of goldsmiths in town in 1384 and 1460. This trade couldn't have survived just from local demand in a town of Birmingham's size.

Medieval Life and Groups

The growth of Birmingham's economy in the 13th and early 14th centuries led to new organizations. St Martin in the Bull Ring was rebuilt in a grand way around 1250. It had two aisles, a clerestory, and a 200-foot-high spire. Two chantries (chapels for prayers) were set up in the church by rich local merchants in 1330 and 1347. The Priory of St Thomas of Canterbury is first mentioned in 1286. By 1310, it had received many gifts of land. The Priory was reformed in 1344 after criticism from the Bishop of Lichfield.

St John's Chapel, Deritend was built around 1380. It was a smaller church linked to the parish church of Aston. Its priest was supported by the Guild of St John, Deritend, which also ran a school. Birmingham's own religious group, the Guild of the Holy Cross, was founded in 1392. This group was a social and political center for the town's important people. It supported priests, almshouses (homes for the poor), a midwife, a clock, the bridge over the River Rea, and helped maintain "dangerous high ways."

Economic success also made the town expand. New Street is first mentioned in 1296. Moor Street was created in the late 13th century, and Park Street in the early 14th century. The population grew because immigrants were attracted by the chance to become traders, free from farm work. Records show that two-thirds came from within 10 miles of the town. Others came from farther away, including Wales, Oxfordshire, and even Paris. There is also some evidence that the town might have had a Jewish population before they were expelled from England in 1290.

Medieval Birmingham was never officially a self-governing city. However, the Borough (the built-up area) was governed separately from the Foreign (the open farmland) from at least 1250. The burgesses of the town elected two bailiffs. The "commonalty of the town" is first recorded in 1296. A grant in 1318 for road repairs was given to "the bailiffs and good men of the town of Bermyngeham," not the lord. This meant the town was free from the strict rules of trade guilds found in fully chartered towns. It was also free from the strict control of a lord.

However, if the 12th and 13th centuries were a time of growth, this stopped in the 14th century due to several disasters. Records from nearby Halesowen mention a "Great Fire of Birmingham" between 1281 and 1313. This might be why pits from the late 13th century under Moor Street contain a lot of charcoal and burnt pottery. Famines from 1315 to 1322 and the Black Death in 1348–50 stopped population growth. A decline in pottery evidence from the 14th and 15th centuries might mean a long period of economic difficulty.

Tudor and Stuart Birmingham (1485–1680)

The Early Modern Town

The Tudor and Stuart eras were a time of big change for Birmingham. In the 1520s, the town was the third largest in Warwickshire with about 1,000 people. This was similar to two centuries before. Despite several plagues in the 17th century, Birmingham's population grew 15 times by 1700. It became the fifth-largest town in England and Wales. Its economy was important nationally, based on growing metal trades. It also gained a reputation for being politically and religiously radical, especially during the English Civil War.

Birmingham's main medieval organizations disappeared between 1536 and 1547. The Priory of St Thomas was closed in 1536 during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The Guild of the Holy Cross and the Guild of St John, Deritend were also disbanded in 1547. Most importantly, the de Birmingham family lost control of the manor of Birmingham in 1536. This was likely due to a conflict between Edward de Birmingham and John Sutton, 3rd Baron Dudley. After being briefly owned by the Crown and the Duke of Northumberland, the manor was sold in 1555 to Thomas Marrow. Birmingham never again had a lord living there. This lack of strong local rule gave the townspeople a lot of economic and social freedom, which was very important for Birmingham's future growth.

This period also saw important cultural developments. Although the Guild of St John, Deritend closed its school, the old hall of the Guild of the Holy Cross was saved. In 1552, King Edward's Free Grammar School was set up using property from the guild. John Rogers, born in Deritend in 1500, became the town's first famous writer. He put together and partly translated the Matthew Bible, the first complete authorized English Bible. The first library in Birmingham was created by 1642. In the same year, Nathaniel Nye, the town's first known scientist, published his New Almanacke and Prognostication. In 1652, the first Birmingham bookseller was recorded, and the first book published in Birmingham was The Font Guarded by local puritan Thomas Hall.

Industry and Economy

In the early 16th century, leather and textile trades were still big in Birmingham. But the making of iron goods became more important. The close link between Birmingham's manufacturers and the raw materials from the area later known as the Black Country was noted by John Leland in 1538. He gave the town's earliest description:

"The beauty of Bremischam, a good market town in the far parts of Warwickshire, is in one street going up almost from the left bank of the brook up a small hill for a quarter of a mile. I saw but one parish church in the town. There are many smiths in the town who make knives and all kinds of cutting tools, and many lorimers who make bits, and a great many nailors. So that a great part of the town is maintained by smiths. The smiths get their iron from Staffordshire and Warwickshire and coal from Staffordshire."

The iron trades grew even more as the century went on. Most of the fulling mills in Birmingham were changed into mills for grinding blades by the end of the century. In 1586, William Camden said the town was "swarming with inhabitants, and echoing with the noise of the anvils, for here are great numbers of smiths and of other artificers in iron and steel, whose performances in that way are greatly admired both at home and abroad."

Birmingham was the business center for manufacturing across the Birmingham Plateau. This area was part of a network of iron forges and furnaces stretching from South Wales to Cheshire. While 16th-century records show nailers in Moseley and Harborne, and bladesmiths in Witton and Erdington, the ironmongers (merchants who organized money, supplied materials, and sold products) were in Birmingham itself. Birmingham ironmongers sold many bills to the Royal Armouries as early as 1514. By the 1550s, Birmingham merchants traded in London, Bristol, and Norwich. By 1596, Birmingham men sold arms in Ireland. By 1657, Birmingham's metalware was known in the West Indies. By 1600, Birmingham was one of the two main places for iron merchants in the country, along with London. It grew because of its economic freedom and closeness to manufacturers and raw materials.

The focus of iron merchants in Birmingham was important for the town's manufacturing. Because of Birmingham's wide trade links, metalworkers could specialize in more different activities. Over the 17th century, simpler trades like making nails, scythes, and bridles moved west to the towns that became the Black Country. Birmingham itself focused on more specialized, higher-skilled, and more profitable work. Tax records for Birmingham in 1671 and 1683 show the number of forges in town increased from 69 to 202. The later records also show many more trades, like hiltmakers, bucklemakers, scalemakers, pewterers, wiredrawers, locksmiths, swordmakers, and workers in solder and lead. Birmingham's economic flexibility was clear early on. Workers and businesses often changed trades or did more than one. Having many skilled manufacturers without strict trade guild rules helped new industries grow. The variety of goods made in late-17th century Birmingham and its international fame were noted by a French traveler, Maximilien Misson. He visited Milan in 1690 and found "fine works of rock crystal, swords, heads of canes, snuff boxes, and other fine works of steel," but then said "they can be had better and cheaper at Birmingham."

Politics, Religion, and Civil War

By the early 17th century, Birmingham's strong economy was run by self-made merchants and manufacturers, not traditional landowners. Its population was growing, and people could easily move up in society. There were almost no rich aristocrats in the area. This created a new kind of society, different from older towns. Relationships were based more on business than on the strict rules of feudal society. The town was seen as a place where loyalty to the traditional church and rich families was weak. The first signs of Birmingham's growing political awareness appeared in the 1630s. A series of puritan lectures encouraged questioning the rules of the Church of England. In 1640, a puritan-inspired petition by townspeople against the local judge, Sir Thomas Holte, showed the first conflict with the country gentlemen who ran local government.

When the English Civil Wars started in 1642, Birmingham became a symbol of puritan and Parliamentarian ideas. The Royalist Earl of Clarendon's History of the Rebellion called the town "disloyal to the king." When 400 armed men from Birmingham arrived, it helped Coventry refuse to let Charles I in, making Warwickshire a Parliamentarian stronghold. As the King's army marched south in October 1642, they met strong local resistance. Troops led by Prince Rupert of the Rhine were ambushed in Moseley and King's Norton. Birmingham townspeople attacked the King's baggage train, stealing his belongings and taking them to Warwick Castle. Birmingham's metal trades were also important. One report said the town's main mill made 15,000 swords just for Parliamentarian forces.

The Royalists got their revenge on April 3, 1643. Prince Rupert returned to Birmingham with 1,200 cavalry, 700 foot soldiers, and 4 guns. The Royalists were pushed back twice by 200 defenders behind quick earthworks. But the cavalry went around the defenses and took over the town in the Battle of Birmingham. They burned 80 houses and killed 15 townspeople. Although the Royalist victory wasn't very important militarily, and the Earl of Denbigh died, the resistance of mostly civilians against the royal cavalry, and the town's destruction, gave the Roundheads a big propaganda boost. This was used in many widely shared leaflets.

Later in the Civil War, Birmingham's manufacturing-based society was shown by the local Parliamentarian colonel John "Tinker" Fox. He gathered 200 men from the Birmingham area and took over Edgbaston Hall from 1643. From there, he attacked the Royalist forces at nearby Aston Hall, gained control of the countryside towards Royalist Worcestershire, and launched bold raids. Fox was very active and largely independent. To Royalists, he symbolized a dangerous overthrow of the established order. Because of his background in Birmingham's metal trades, he was called a tinker. By 1649, he was so famous that people rumored he was Charles I's executioner.

The Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution (1680–1791)

New Ideas and Industries

The 18th century saw Birmingham become a leader in science, technology, medicine, and philosophy. This period is known as the Midlands Enlightenment. By the late 1700s, the town's top thinkers, especially members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham like Joseph Priestley, James Watt, and Erasmus Darwin, were important figures in the exchange of ideas across Europe and America. The Lunar Society was "the most important private scientific group in 18th-century England." The Midlands Enlightenment was a key part of the English Enlightenment. It also had strong links with other major centers of the Age of Enlightenment.

People used to think this "miracle birth" happened because Birmingham was a stronghold of religious Nonconformism. This meant a free-thinking culture, not controlled by the official Church of England. This fits with ideas that Protestant culture helped science and capitalism grow in Europe. Birmingham had a strong Nonconformist community by the 1680s, even before they had full freedom to worship. By the 1740s, this group became influential. About 15% of Birmingham households were Nonconformists in the mid-18th century, compared to 4–5% nationally. Presbyterians and Quakers had a lot of influence in the town. They often held the position of Low Bailiff, the most powerful local government role, from 1733. They also made up over a quarter of the Birmingham Street Commissioners appointed in 1769, even though they were legally barred from holding office until 1828. Despite this, Birmingham's Enlightenment wasn't just Nonconformist. Lunar Society members had different religious backgrounds, and Anglicans were the majority in all parts of Birmingham society.

New research shows that the Midlands Enlightenment wasn't mainly about industry or technology. Lunar Society meetings focused on pure science, not manufacturing. The ideas of Midlands Enlightenment thinkers influenced education, philosophy, poetry, the theory of evolution, and photography. However, a special feature of the Midlands Enlightenment was the close link between scientists and manufacturers. This was partly due to Birmingham's high social mobility. The Lunar Society included industrialists like Samuel Galton, Jr. and thinkers like Erasmus Darwin. Scientists like John Warltire taught basic science to the town's manufacturers. Men like Matthew Boulton and James Watt were respected as both scientists and technologists, and sometimes as businessmen. So, the intellectual atmosphere in 18th-century Birmingham was very good for sharing knowledge from science to manufacturing. This created a "chain reaction of innovation."

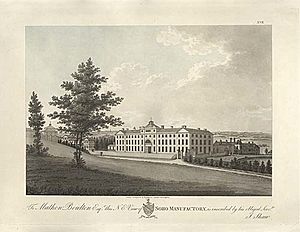

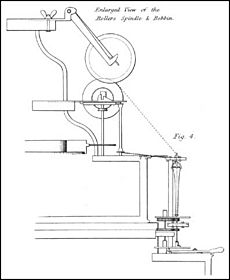

The Midlands Enlightenment was a key link between the growth of knowledge in the earlier Scientific Revolution and the economic growth of the Industrial Revolution. In 18th-century Birmingham, reason, experiments, and scientific knowledge were applied to manufacturing more than ever before. This led to many new technologies and economic ideas that changed many industries. It laid the groundwork for modern industrial society. In 1709, Abraham Darby I, who trained in Birmingham, successfully used coke to smelt iron in a blast furnace. In 1732, Lewis Paul and John Wyatt invented roller spinning, a very important idea for the mechanized cotton industry. In 1741, they opened the world's first cotton mill in Birmingham. In 1765, Matthew Boulton opened the Soho Manufactory. He was a pioneer in combining and mechanizing different manufacturing steps under one roof. By the end of the decade, this was the largest factory in Europe, with over 1,000 employees. It was a symbol of the new factory system. John Roebuck's 1746 invention of the lead chamber process allowed large-scale production of sulphuric acid. James Keir pioneered making alkali. These two developments marked the start of the modern chemical industry.

The most important technological innovation of the Midlands Enlightenment was the 1775 development of the industrial steam engine by James Watt and Matthew Boulton. This engine had four new technical improvements that allowed it to cheaply and efficiently create the spinning motion needed to power factory machines. This invention freed society's ability to produce goods from the limits of hand, water, and animal power. It was arguably the most important development of the entire Industrial Revolution. Without it, the huge increases in economic activity in the next century would have been impossible.

Business and Industry Growth

Birmingham's huge industrial growth started before that of the textile towns in the North of England. It can be traced back to the 1680s. Birmingham's population grew four times between 1700 and 1750. By 1775, before the start of machine use in the Lancashire cotton trade, Birmingham was already the third most populated town in England. It was smaller only than London and Bristol and was growing faster than any other town. As early as 1791, the economist Arthur Young called Birmingham "the first manufacturing town in the world."

The reasons for Birmingham's fast industrialization were different from those that later drove textile towns like Manchester. Manchester's growth from the 1780s was based on making large amounts of cheap goods like cotton with low-wage, unskilled workers. Although the inventions that made this possible (like roller spinning and the industrial steam engine) often came from Birmingham, they didn't play a big role in Birmingham's own growth. Birmingham's location meant its industries focused on making many small, valuable metal items, from buttons and buckles to guns and jewellery. Its economy had high wages and many specialized skills that couldn't be fully automated. Small workshops, not large factories, were typical in Birmingham throughout the 18th century. Steam power didn't become very important in Birmingham until the 1830s.

Instead of low wages and huge scale, Birmingham's manufacturing grew because of a highly skilled workforce, specialization, flexibility, and especially, new ideas. It was easy to start a business in Birmingham, which led to a lot of entrepreneurial activity. William Hutton described trades that "spring up with the expedition of a blade of grass, and, like that, wither in the summer." In terms of manufacturing technology, Birmingham was by far the most inventive town of that time. Between 1760 and 1850, Birmingham residents registered over three times as many patents as any other town. Most of these were small, continuous improvements. Matthew Boulton noted in 1770 how their machines allowed workers to do "from twice to ten times the work." New ideas also came in production methods, especially in dividing labor into many small steps. People at the time noted that in Birmingham, even simple products like buttons went through 50 to 70 different steps, done by as many different workers. This gave Birmingham a competitive edge.

New ideas also applied to Birmingham's products, which were made for its merchants' national and international connections. In the first half of the century, growth was mainly driven by the domestic market. But foreign trade became important in the mid-century and was the main factor from the 1760s and 1770s. This trade was influenced by the markets and fashions of London, France, Italy, Germany, Russia, and the American colonies. Birmingham's economy could adapt quickly to fashion changes. For example, the market for buckles collapsed in the late 1780s, but workers simply switched to making brass or buttons. Birmingham manufacturers aimed for leading designs in London or Paris, then priced their goods for the growing middle class. New products and materials were adopted: the town's first glasshouse opened in 1762, papier-mâché manufacturing grew from 1772, and minting of coins started in 1786.

Besides its own specialized manufacturing, Birmingham remained the business center for a regional economy that included basic manufacturing and raw material production from Staffordshire and Worcestershire. The need for capital to fund rapid economic growth made the town a major financial centre with international links. In the early 18th century, money mostly came from iron merchants and trade credit. It was an iron merchant, Sampson Lloyd, and a major manufacturer, John Taylor, who together formed the town's first bank, the early Lloyds Bank, in 1765. More banks followed, and by 1800, the West Midlands had more banking offices per person than any other region in Britain, including London. Birmingham's booming economy led to a growing professional sector. The number of doctors and lawyers increased by 25% between 1767 and 1788. It's estimated that between a quarter and a third of Birmingham's people were middle class in the late 18th century. This led to a big demand for tailors, mercers, and drapers. Trade directories show more drapers than tool makers in 1767. Insurance records from 1777 to 1786 suggest that over half of local businesses were in trading or services, not directly in industry.

Enlightenment Society

Georgian Birmingham saw a huge growth in public spaces for sharing ideas, which was a key part of Enlightenment society. Clubs, taverns, and coffeehouses became popular places for people to meet, cooperate, and debate. These places often brought together people from different social classes. While the Lunar Society of Birmingham is the most famous, William Hutton described hundreds of such groups in Birmingham with thousands of members. A German visitor, Philipp Nemnich, noted that "the inhabitants of Birmingham are fonder of associations in clubs than almost any other place I know." Important examples included Freeth's Coffee House, a famous meeting place; Ketley's Building Society, the world's first building society, founded in 1775; and the Birmingham Book Club, known for its radical politics. These groups played a big role in the growing political awareness in the town. There was also the more traditional Birmingham Bean Club, which brought together loyal figures and landowners.

Printed materials were another growing way to share ideas. Georgian Birmingham had a very literate society. By 1733, there were at least seven booksellers. The largest in 1786 claimed to have 30,000 books in several languages. Eight or nine commercial lending libraries opened during the 18th century. It was said that Birmingham's population of about 50,000 read 100,000 books per month. More specialized libraries included St. Philip's Parish Library (1733) and the Birmingham Library (1779), founded by a group of dissenting subscribers for research. Birmingham had been a center for printing and publishing since the 1650s. The rise of John Baskerville and other printers he attracted in the 1750s made this internationally important. The town's first newspaper was the Birmingham Journal, founded in 1732. It was short-lived but famous as the first place Samuel Johnson's work was published. Aris's Birmingham Gazette, founded in 1741, became "one of the most profitable and important provincial papers" of 18th-century England. By the 1770s, it circulated as far as Chester and London. The more radical Swinney's Birmingham Chronicle claimed in 1776 that it circulated across nine counties. News from outside the town also spread widely. Freeth's Coffeehouse in 1772 had an archive of London newspapers going back 37 years and received direct reports from Parliament.

Birmingham's booming economy attracted immigrants from a wide area. Many kept their freeholds (and thus votes) in their old areas. This gave Birmingham's politics a wide influence, even though the town had no parliamentary representation of its own. A clear and powerful "Birmingham interest" appeared with the election of Thomas Skipwith in 1769. Over the next decades, candidates for seats in places like Worcester and Leicester sought support in the town.

Transport and Town Growth

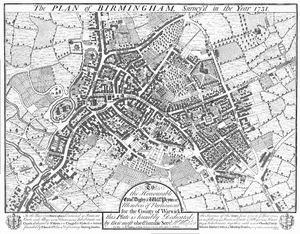

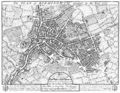

The first map of Birmingham was made in 1731 by William Westley. The year before, he showed a newly built area called Old Square, which became a very fancy address. This wasn't the first map to show Birmingham, but earlier ones just used a small symbol. S. Bradford surveyed Birmingham again in 1750.

Until the 1760s, Birmingham's local government was run by part-time, unpaid officials. This system couldn't handle Birmingham's fast growth. In 1768, Birmingham got a basic local government system. A group called "Commissioners of the Streets" was set up. They could collect taxes for things like cleaning and street lighting. Later, they were given powers to provide policing and build public buildings.

From the 1760s onwards, Birmingham became a center of the canal system. Canals provided an efficient way to transport raw materials and finished goods. This greatly helped the town's industrial growth.

The first canal into Birmingham opened in November 1769. It connected Birmingham with the coal mines at Wednesbury in the Black Country. Within a year, the price of coal in Birmingham dropped by 50%.

The canal network across Birmingham and the Black Country grew quickly in the following decades. Most of it was owned by the Birmingham Canal Navigations Company. Other canals, like the Worcester and Birmingham Canal and the Birmingham and Fazeley Canal, linked Birmingham to the rest of the country. By 1830, about 160 miles of canal had been built in the Birmingham and Black Country area.

Because of its many industries, Birmingham was nicknamed "workshop of the World." The town's growing population and wealth led to a library in 1779, a hospital in 1766, and various recreational places.

Victorian Birmingham (1832–1914)

Horatio Nelson and the Hamiltons visited Birmingham. Nelson was celebrated and visited Matthew Boulton at Soho House. He toured the Soho Manufactory and ordered a medal for the Battle of the Nile. In 1809, a statue of Horatio Nelson was put up in the Bull Ring, paid for by public donations. It's still there today.

The Birmingham Manor House and its moat were torn down in 1816. The site was used to build the Smithfield Markets. These markets brought various trading activities to one area near the Bull Ring, which had become a shopping district.

At the start of the 19th century, Birmingham had about 74,000 people. By the end of the century, it had grown to 630,000. This fast growth meant that by the mid-century, Birmingham was the second largest population center in Britain.

Railways Arrive

Railways came to Birmingham in 1837 with the opening of the Grand Junction Railway. This line connected Birmingham with Manchester and Liverpool. The next year, the London and Birmingham Railway opened, linking the city to the capital. Soon after, the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway and the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway also opened.

These lines first had separate stations around Curzon Street. However, in the 1840s, these early railway companies merged. The two main companies, the London and North Western Railway and the Midland Railway, built Birmingham New Street Station together. It opened in 1854, and Birmingham became a central hub of the British railway system.

In 1852, the Great Western Railway arrived in Birmingham. A second, smaller station, Snow Hill, was opened. This line connected the city with Oxford and London Paddington.

Political Changes

Also in the 1830s, because of its growing size and importance, Birmingham gained Parliamentary representation. The Reform Act of 1832 created the new Birmingham constituency with two Members of Parliament (MPs). Thomas Attwood and Joshua Scholefield, both Liberals, were elected as Birmingham's first MPs.

In 1838, local government reform meant Birmingham was one of the first new towns to become a municipal borough. This was allowed by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835. This meant Birmingham had its first elected town council. The council first worked with the existing Street Commissioners, until they were closed down in 1851.

Industry and Business

Birmingham's growth and wealth came from its metalworking industries, which included many different types.

Birmingham became known as the "City of a thousand trades." This was because of the wide variety of goods made there. Buttons, cutlery, nails, screws, guns, tools, jewellery, toys, locks, and ornaments were among the many products manufactured.

For most of the 19th century, Birmingham's industry was dominated by small workshops, not large factories. Big factories became more common towards the end of the century as engineering industries grew in importance.

Birmingham's industrial wealth allowed merchants to pay for the building of impressive public buildings. Some 19th-century buildings included: the Birmingham Town Hall (1834), the Birmingham Botanical Gardens (1832), the Council House (1879), and the Museum and Art Gallery (1885).

The mid-19th century saw many people move to the city from Ireland, following the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849).

Birmingham became a county borough and a city in 1889.

Improvements in the City

Like many industrial towns in the 19th century, many of Birmingham's residents lived in crowded and unhealthy conditions. In the early to mid-19th century, thousands of back-to-back houses were built for the growing population. Many were poorly built and drained, and soon became slums.

In 1851, a network of sewers was built under the city and connected to the River Rea. However, only new houses were connected at first. Many older houses had to wait decades.

Birmingham got gas lighting in 1818 and a water company in 1826 to provide piped water. But clean water was only available to those who could pay. Birmingham got its first electricity supply in 1882. Horse-drawn trams ran through Birmingham from 1873, and electric trams from 1890.

In the mid-1840s, the inspiring preacher George Dawson started promoting ideas of social responsibility and city improvement. This became known as the Civic Gospel. His ideas inspired a group of reformers, including Joseph Chamberlain. From the late 1860s, these reformers were elected to the Town Council as Liberals. They put these ideas into practice. This period was at its best during Chamberlain's time as mayor, from 1873 to 1876. Under his leadership, Birmingham changed greatly. The council started one of the most ambitious improvement plans outside London. The council bought the city's gas and water works. They improved lighting and provided clean drinking water. The money from these services also gave the council a good income, which was reinvested into the city for new facilities.

Under Chamberlain, some of Birmingham's worst slums were cleared. A new main street, Corporation Street, was built through the city center. It soon became a popular shopping street. He also helped build the Council House and the Victoria Law Courts in Corporation Street. Many public parks were created. Central libraries opened in 1865–6, and the city's Museum and Art Gallery in 1885. The improvements made by Chamberlain and his colleagues became a model for city governments and were soon copied by other cities. By 1890, an American journalist called Birmingham "the best-governed city in the world." Even after resigning as mayor to become an MP, Chamberlain remained very interested in the city for many years.

Birmingham's water problems were not fully solved by reservoirs in Walmley Ash. Larger reservoirs were built at Witton Lakes and Brookvale Park Lake. The problems were finally solved by the Birmingham Corporation Water Department with the completion of a 73-mile-long Elan aqueduct. This aqueduct was built to a reservoir in the Elan Valley in Wales. This project was approved in 1891 and finished in 1904.

Wartime and Between Wars (1914–1945)

The First World War had a terrible human cost in Birmingham. More than 150,000 men from the city, over half of the male population, served in the armed forces. Of these, 13,000 were killed and 35,000 wounded. The start of machine warfare also made Birmingham more important as a center for industrial production. The British Commander-in-Chief, John French, described the war as "a battle between Krupps and Birmingham." At the end of the war, Prime Minister David Lloyd George also recognized Birmingham's importance in the Allied victory. He said, "the country, the empire and the world owe to the skill, the ingenuity and the resource of Birmingham a deep debt of gratitude." Some Birmingham men were conscientious objectors (people who refused to fight for moral reasons).

In 1918, the Birmingham Civic Society was founded. Its goal was to bring public attention to all plans for building, new open spaces, and anything else related to the city's appearance. The society made suggestions for improvements. Sometimes they designed and paid for improvements themselves. They also bought several open spaces and later gave them to the city to be used as parks.

After the Great War ended in 1918, the city council decided to build modern housing across the city. This was to rehouse families from inner-city slums. Recent boundary expansions brought areas like Aston, Handsworth, Erdington, Yardley, and Northfield into the city. This provided extra space for new housing. By 1939, when the Second World War started, almost 50,000 council houses had been built across the city in 20 years. About 65,000 houses were also built for people to own. New council estates built during this time included Weoley Castle, Pype Hayes, and the Stockfield Estate at Acocks Green.

In 1936, King Edward's Grammar School on New Street was torn down and moved to Edgbaston. The school had been on that site for 384 years. The site later became an office block, which was destroyed in the Second World War bombing. It was rebuilt and named "King Edward's House," now used for offices, shops, and restaurants.

In the First and Second World Wars, the Longbridge car plant switched to making military equipment. This included ammunition, mines, depth charges, tank suspensions, steel helmets, Jerricans, Hawker Hurricanes, Fairey Battle fighters, and Airspeed Horsa gliders. The huge Avro Lancaster bomber was produced towards the end of WWII. The Spitfire fighter aircraft was mass-produced at Castle Bromwich by Vickers-Armstrong throughout the war.

Birmingham's industrial importance and contribution to the war effort may have been crucial in winning the war. The city was heavily bombed by the German Luftwaffe during the Birmingham Blitz in World War II. By the war's end, 2,241 citizens had been killed by bombing, and over 3,000 seriously injured. 12,932 buildings were destroyed (including 300 factories), and thousands more damaged. The air raids also destroyed many of Birmingham's fine buildings. The council declared five redevelopment areas in 1946:

- Duddeston and Nechells

- Summer Lane

- Ladywood

- Bath Row

- Gooch Street

Post-War Birmingham (1945–1975)

Less Local Control and Growth Limits

A key change for Birmingham after the war was losing much of its independence. World War II saw a huge increase in the role of the central government in British life. This continued after the war. For Birmingham, it meant major decisions about the city's future were often made outside the city, mainly in Westminster. Planning, development, and city services were increasingly controlled by national policies. City council money came mostly from central government. Services like gas, water, and transport were taken out of the city's control. Birmingham's size and wealth might have given it more political influence than other cities, but like all of them, it was under the control of Whitehall. The days of Birmingham acting like a semi-independent city-state were over.

This had big effects on how the city developed. Until the 1930s, Birmingham's leaders always assumed their job was to help the city grow. However, after the war, national governments saw Birmingham's fast economic success as harmful to the struggling economies of the North of England, Scotland, and Wales. They also saw its physical expansion as a threat to nearby areas. From Westminster's view, Birmingham was "too large, too prosperous, and had to be held in check." A series of rules, starting with the Distribution of Industry Act 1945, aimed to stop industrial growth in "Congested Areas" (like London and Birmingham). The goal was to encourage industries to move to economically struggling "Development Areas" in the north and west. The West Midlands Plan in 1946 set a target population for Birmingham in 1960 at 990,000. This was much less than its actual 1951 population of 1,113,000. This meant 220,000 people would have to leave the city over 14 years. Some industries would have to move, and new ones would be prevented from starting in the city. By 1957, the council agreed it had to "restrain the growth of population and employment potential within the city."

With less power over its own future, Birmingham lost most of its unique political character. The General Election of 1945 was the first in 70 years where no member of the Chamberlain family ran for Birmingham.

Economic Boom and Restrictions

Birmingham's economy thrived in the 30 years after World War II. Its economic strength and wealth far surpassed other major British cities. Changes in the economy over the previous 50 years meant the West Midlands was strong in two of Britain's three main growth areas: motor vehicles and electrical equipment. Birmingham itself was second only to London for creating new jobs between 1951 and 1961. Unemployment in Birmingham between 1948 and 1966 rarely went above 1%. By 1961, household incomes in the West Midlands were 13% above the national average, even higher than London.

This prosperity happened despite strict rules placed on the city's economy by the central government, which wanted to limit Birmingham's growth. The Distribution of Industry Act 1945 banned industrial development over a certain size without a special "Industrial Development Certificate." The hope was that companies refused permission to expand in London or Birmingham would move to struggling cities in the North of England. At least 39,000 jobs were directly moved out of the West Midlands by factory relocations between 1960 and 1974. Planning rules also made local firms like British Motor Corporation expand in South Wales and Scotland instead of Birmingham. Government rules also indirectly discouraged economic development in the city. Limits on the city's physical growth during an economic boom led to very high land prices and a lack of building sites. Moves to reduce the city's population led to labor shortages and rising wages.

Although jobs in Birmingham's limited manufacturing sector shrank by 10% between 1951 and 1966, this was more than made up for by jobs in the service sector in the early post-war period. Service jobs grew from 35% of the city's workforce in 1951 to 45% in 1966. As the business center of the country's most successful regional economy, Central Birmingham was the main focus outside London for the post-war office building boom. Service sector employment in the Birmingham area grew faster than in any other region between 1953 and 1964. During the same period, 3 million square feet of office space were built in the city center and Edgbaston. The city's economic boom led to the rapid growth of a large merchant banking sector, as major London and international banks opened offices in the city. Professional and scientific services, finance, and insurance also grew very strongly. However, this service sector growth itself attracted government restrictions from 1965. The Labour Government of 1964 called the growth in population and jobs in Birmingham a "threatening situation." They aimed "to control the growth of office accommodation in Birmingham... in the same way as they control the growth of industrial employment." Although the City Council had encouraged service sector growth in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the central government extended the Control of Office Employment Act 1965 to Birmingham from 1965. This effectively banned all further office development for almost two decades.

These policies had a major impact on the city's economy. While government policy had limited success in stopping the growth of Birmingham's existing industries, it was much more successful in preventing new industries from starting in the city. Birmingham's economic success over the previous two centuries was built on its diverse economy and its ability to adapt and innovate. It attracted new businesses and developed new industries with its skilled workers and entrepreneurial culture. But this was exactly what government policy tried to prevent. Birmingham's existing industries grew strongly and kept the economy healthy. However, growing local fears that the city's economy was becoming too specialized were dismissed by the central government, even though warning signs appeared by the early 1970s. In 1950, Birmingham's economy was described as "more broadly based than that of any city of equivalent size in the world." But by 1973, the West Midlands relied more on large firms for jobs. The small firms that remained increasingly depended on a few larger firms as suppliers. The "City of Thousand Trades" had become too specialized in one industry, the motor trade. By the 1970s, much of this had become one company, British Leyland. Trade union organization grew, and the motor industry, in particular, saw labor disputes from the 1950s onwards. A city that had been known for weak trade unions and good cooperation between workers and management developed a reputation for union activism and industrial conflict.

Despite more than 150,000 houses being built in the city for both private and public sectors since 1919, 20% of the city's homes were still considered unfit to live in by 1954. 37,000 council properties were built between 1945 and 1954 to rehouse families from the slums. By 1970, the housing crisis was easing as that figure had exceeded 80,000.

City Planning and Rebuilding

In the post-war years, a huge program of slum clearances took place. Large areas of the city were rebuilt. Crowded "back to back" houses were replaced by high-rise blocks of flats. (The last remaining block of four back-to-backs has become a museum run by the National Trust.)

Due largely to bomb damage, the city center was also extensively rebuilt under the direction of the city council's chief engineer, Herbert Manzoni. He was helped by several people who held the City Architect position. A symbol of this rebuilding was the new Bull Ring Shopping Centre. Birmingham also became a center of the national motorway network, with Spaghetti Junction. Much of the post-war rebuilding would later be seen as a mistake, especially the many concrete buildings and ring roads that gave the city a reputation for ugliness.

Council house building in the first decade after World War II was extensive. More than 37,000 new homes were completed by the end of 1954. These included the first of several hundred multi-story blocks of flats. Despite this, about 20% of the city's houses were still reported to be unfit for people to live in. As a result, mass council house building continued for about 20 more years. Existing suburbs continued to grow, while several completely new housing estates were developed.

Castle Bromwich, which grew into a new town, was developed about six miles east of the city center during the 1960s. Castle Vale, near the Fort Dunlop tire factory northeast of the city center, was developed in the 1960s as Britain's largest post-war housing estate. It had 34 tower blocks, though 32 of them were torn down by the end of 2003 as part of a huge regeneration project. This was due to the general unpopularity and problems associated with such developments.

In 1974, 21 people were killed and 182 injured when two city-center pubs were bombed by the IRA.

In the same year, as part of a local government reorganization, Birmingham expanded again. This time it took over the borough of Sutton Coldfield to the north. Birmingham lost its county borough status and became a metropolitan borough under the new West Midlands County Council. It was also finally removed from Warwickshire.

New People and Cultures

There were more waves of immigration from Ireland in the 1950s and 1980s. People moved to escape economic hardship and unemployment in their homeland. There is still a strong Irish tradition in the city, especially in Digbeth's Irish Quarter and in the annual St Patrick's Day parade. This parade is said to be the third-largest in the world after New York and Dublin.

In the years after World War II, many immigrants from the Commonwealth of Nations came to Birmingham. Large communities from Southern Asia and the Caribbean settled in the city. This made Birmingham one of the UK's leading multicultural cities.

However, not everyone welcomed these changes. The right-wing Wolverhampton MP Enoch Powell gave his famous Rivers of Blood speech in the city on April 20, 1968.

On the other hand, some arts thrived, especially music. Birmingham had lively heavy metal (with bands like Black Sabbath and Judas Priest) and reggae scenes (with local artists like Steel Pulse and UB40).

Since the early 1980s, Birmingham has seen a new wave of migration. This time, people came from communities without Commonwealth roots, such as Kosovo and Somalia. More immigration from Eastern Europe (especially Poland) happened with the expansion of the European Union in 2004.

Tension between ethnic groups and authorities led to the Handsworth riots in 1981 and 1985. In October 2005, the 2005 Birmingham riots happened in the Lozells and Handsworth areas. There were street battles between black and Asian gangs, resulting in two deaths and much damage.

The Birmingham City Council, along with the 'Be Birmingham' partnership, continues to work towards a better, more united Birmingham.

Modern Birmingham (1975–Present)

Birmingham's industrial economy collapsed suddenly and badly. As late as 1976, the West Midlands region, with Birmingham as its main economic driver, still had the highest GDP in the UK outside the South East. But within five years, it was the lowest in England. Birmingham itself lost 200,000 jobs between 1971 and 1981, mostly in manufacturing. Earnings in the West Midlands went from being the highest in Britain in 1970 to the lowest in 1983. By 1982, the city's unemployment rate was almost 20%, and about twice that in inner-city areas like Aston and Handsworth.

The City Council decided to change the city's economy. They focused on service industries, retail, and tourism to rely less on manufacturing. Several projects were started to make the city more attractive to visitors.

In the 1970s, the National Exhibition Centre (NEC) was built. It's 10 miles southeast of the city center, near Birmingham International Airport. Although it's technically in neighboring Solihull, Birmingham Council started and largely owns it, and most people think of it as being in Birmingham. It has been expanded several times since then.

The International Convention Centre (ICC) opened in central Birmingham in the early 1990s. The area around Broad Street, including Centenary Square, the ICC, and Brindleyplace, was greatly improved around 2000. In 1998, a G8 summit (a meeting of leaders from major industrial nations) was held in Birmingham. US president Bill Clinton was clearly impressed by the city.

The city's regeneration in the 1990s and 2000s also saw many residential areas greatly changed. A notable example was the Pype Hayes council estate, built between the wars. It was completely redeveloped due to structural problems. Many of the city's 1960s council properties, mostly high-rise flats, have also been torn down in similar redevelopments. This includes the large Castle Vale estate, where all but two of its 34 tower blocks were demolished as part of a huge regeneration. This estate had been badly affected by crime, unemployment, and poor housing.

In September 2003, the Bullring shopping complex opened after a three-year project. In 2003, the city tried to become the 2008 European Capital of Culture with the slogan "Be in Birmingham 2008", but it didn't win.

Birmingham continues to develop. The Birmingham Inner Ring Road, which acted like a "concrete collar" stopping the city center from expanding, has been removed. A massive urban regeneration project called the Big City Plan is underway. For example, the city's new Eastside district is undergoing work expected to cost £6 billion.

The city was affected by the riots that spread through the country in August 2011. These resulted in widespread criminal damage in several inner-city areas and three deaths in the Winson Green area.

Historic Population

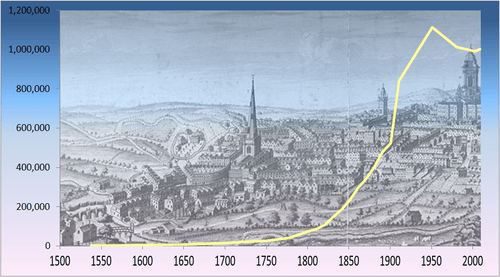

- 1538 — 1,300

- 1550 — 1,500

- 1650 — 5,472

- 1700 — 15,032

- 1731 — 23,286

- 1750 — 24,000

- 1778 — 42,250

- 1785 — 52,250

- 1800 — 74,000

- 1811 — 85,753

- 1821 — 106,722

- 1831 — 146,986

- 1841 — 182,922

- 1851 — 232,638

- 1861 — 296,076

- 1871 — 343,787

- 1881 — 400,774

- 1891 — 478,113

- 1901 — 522,204 in the city proper, 630,162 in the urban area.

- 1911 — 840,202

- 1951 — 1,113,000 (population peak)

- 1981 — 1,013,431

- 2001 — 977,087

- 2011 — 1,074,300

Images for kids

-

The Saltley Handaxe illustrated by John Evans in 1897

-

The Roman Icknield Street in Sutton Park

-

Entry for Birmingham in Domesday Book

-

Fourteenth-century alabaster effigy of John de Birmingham in St Martin in the Bull Ring

-

Birmingham's first cartographic representation, on the fourteenth century Gough Map. The town (centre) is shown within the Forest of Arden, on the road between Lichfield (left) and Droitwich (right). North is to the left

-

Deritend ware jug and sherds

-

The Old Crown, originally the hall of the Guild of St John, Deritend, is the sole surviving secular building of medieval Birmingham

-

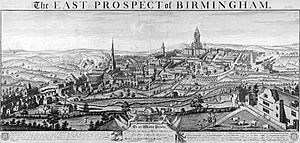

Engraving of Birmingham by Wenceslas Hollar, published in 1656

-

John Rogers, compiler of the first complete authorised edition of the Bible to appear in the English language

-

Soho House, regular venue for meetings of the Lunar Society of Birmingham

-

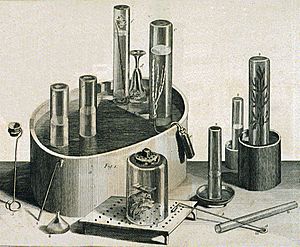

Equipment used by Joseph Priestley in his experiments on gases

-

Detail from Lewis Paul's 1758 second patent for a roller spinning machine

-

John Freeth and his Circle – the radical Birmingham Book Club, which met at Freeth's Coffee House

-

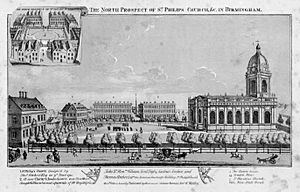

Two early 18th century developments – St. Philip's Church and (inset) Old Square – illustrated in 1732

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |