Enclosure facts for kids

Enclosure (sometimes called inclosure) was a way of changing how land was owned and used in England. It involved taking "waste" land (land not officially used) or "common land" (land shared by many people) and fencing it off. This meant that ordinary people, called commoners, lost their traditional rights to use that land for things like grazing animals or collecting wood.

Enclosure could happen in different ways. Sometimes, individual landowners would fence off parts of larger common fields. Other times, groups of landowners, like small farmers or squires, would work together to enclose entire areas. The most formal way was through special laws passed by Parliament, called Inclosure Acts.

The main reason for enclosure was to make farming more efficient and productive. Enclosed land also became much more valuable. However, these changes had big social effects. Many people protested because they lost their rights. Historians see these "enclosure riots" as a major form of social protest from the 1530s to the 1640s.

Contents

History of Enclosure

After William the Conqueror took over England in 1066, he divided the land among his important followers, called barons. This created a feudal system, where land was held in exchange for service. However, William also promised to keep the old laws, so common people still had their traditional rights to use certain lands. Over time, the service agreements often changed into money payments.

In the 13th century, wealthy lords did very well, but peasants struggled as their costs increased and their landholdings shrank. Then, in the mid-14th century, the Black Death caused a huge drop in population and crop yields. This meant there were fewer farm workers, so those who survived were in high demand. Landowners had to either pay higher wages or leave their land unused. Wages went up, which led to inflation. Many historians believe this labor shortage helped end the feudal system, though some think it just sped up a process already happening.

Enclosing land started as early as the 12th century, but it happened differently across England. Some areas, like parts of Essex and Kent, always had small, enclosed fields from ancient times. In other parts, fields were either never open or were enclosed very early. The main area where the "open field system" (where land was shared) was common was in the lowland areas, stretching from Yorkshire down through the Midlands to the south.

What Do These Words Mean?

Enclosure

- It was the removal of common rights that people had over farmland and shared village lands.

- It meant taking scattered strips of land and combining them into large new fields, which were then fenced off with hedges, walls, or fences.

- These new enclosed fields were only for the use of individual owners or the people who rented from them.

Villagers

- Lord of the manor: The main landowner in a village or area.

- Freeholders or yeoman: People who owned their land outright, whether large or small properties.

- Copyhold: People who had a traditional right to use land, recorded in the manor's books.

- Tenant farmers: People who rented land from a lord or landowner.

- Cottagers/cottar: People who lived in small houses (cottages) and often had a small piece of land.

- Squatters: People who lived on land without official permission.

- Farm servants: People who worked on farms and lived in their employer's house.

How Enclosure Happened

Enclosure generally happened in two main ways: 'formal' or 'informal' agreements. Formal enclosure was done either through a special law passed by Parliament (after 1836) or by a written agreement signed by everyone involved. These written agreements often included a map.

Informal agreements had little or no written record, sometimes just a map. The simplest informal enclosure was called 'unity of possession'. This happened when one person managed to buy all the different strips of land in an area and combine them into one large piece, like a whole manor. When one person owned everything, there was no one else to use the common rights, so those rights disappeared.

The Open Field System

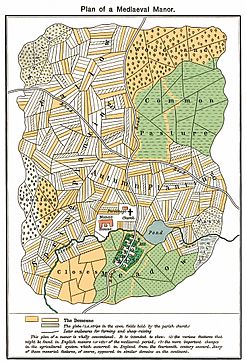

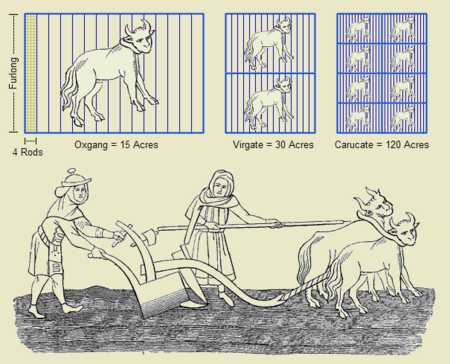

Before enclosure, much of the land in England was part of the "open-field system". In this system, the village land was controlled by the lord of the manor. A typical manor had two main parts: the land farmed by peasants (tenants) and the lord's own farm, called the demesne. The lord's land was for his benefit and was farmed by his workers. Tenant farmers paid rent, which could be money, labor, or crops.

Tenants also had certain rights, like being able to pasture their animals, let their pigs eat acorns in the woods (pannage), or collect wood (estovers). "Waste" land was often small, awkward areas like cliff edges, or bare rock. It wasn't officially used by anyone, so landless peasants sometimes farmed it.

The rest of the land was divided into many narrow strips. Each tenant had several different strips spread out across the manor, and the lord of the manor also had his own strips. The open-field system was managed by local courts, which helped control how the land was used.

Under this system, a manor's land would include:

- Two or three very large shared fields for crops.

- Several very large shared hay meadows.

- Smaller enclosed areas (closes).

- Sometimes, a park.

- Shared "waste" land.

What we might now call a single field was divided among the lord and his tenants. Poorer peasants (like serfs or copyholders) were allowed to live on the lord's land in exchange for working on it. The open-field system likely developed from an older system called the Celtic field system.

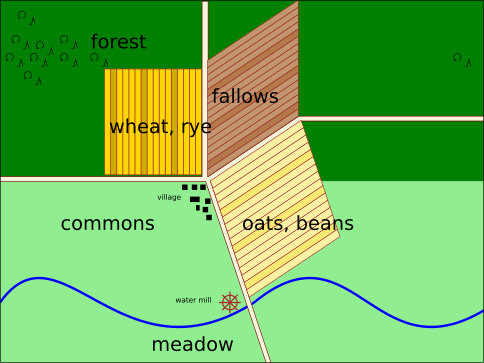

The open-field system used a three-field crop rotation. One field would be planted with barley, oats, or legumes in spring. Another would have wheat or rye in autumn. Since there was no artificial fertilizer in medieval England, growing crops continuously would make the soil less fertile. The open-field system solved this by leaving the third field unplanted (called "fallow") each year. Animals would graze on this fallow field, and their manure would help make the soil fertile again. The next year, the fields for planting and fallow would be rotated.

This three-field system made everyone, both lords and tenants, follow a strict schedule for managing the land. Everyone could do what they wanted with their own strips, but they had to follow the rotation. After harvest, the fields became "common" again, so tenants could graze their livestock (sheep, pigs, cattle, horses, oxen, and poultry) on the leftover stubble. One village, Laxton, Nottinghamshire, still uses the open-field system today.

Why the Open Field System Ended

Landowners wanted to earn more money, so they looked for better farming methods. They saw enclosure as a way to make farming more efficient. But it wasn't just about fencing; it also involved big changes in how farming was done.

One important invention was the Norfolk four-course system. This system greatly increased how much food and livestock could be produced by making the soil more fertile and reducing how long fields were left fallow. Here's how it worked:

- Year 1: Wheat was grown.

- Year 2: Turnips were grown.

- Year 3: Barley was grown, followed by clover and ryegrass.

- Year 4: The clover and ryegrass were grazed by animals or cut for feed.

The turnips were used to feed cattle and sheep in winter. Growing different types of crops in the same area over several seasons helped put nutrients back into the soil and reduced problems with diseases and pests. This system also improved the soil's structure and fertility by using both deep-rooted and shallow-rooted plants. For example, turnips could bring up nutrients from deep in the soil.

Planting crops like turnips and clover wasn't practical under the open-field system because other villagers' animals could freely graze on the fields. The Norfolk system also used workers at times when there wasn't as much demand for labor.

Some open fields in Britain started to be enclosed into individually owned fields as early as the 12th century. After a law called the Statute of Merton in 1235, lords could gather scattered strips of land into one continuous block.

People who held land by "copyhold" had a traditional right to use their land, which was legally protected. However, this right usually only lasted for their lifetime. Their children didn't automatically inherit it, though they could often pay a fee to have the copyhold transferred. To remove these traditional rights, landlords often changed copyhold into "leasehold" tenancy. Leasehold removed the old customary rights, but the advantage for the tenant was that the land could be inherited.

Enclosure greatly increased during the Tudor period. Landowners often enclosed land on their own, sometimes even illegally. This led to many people being forced off their land, causing the open-field system to collapse in those areas. Historians believe that the hardship faced by these displaced workers led to social unrest.

Laws About Enclosure

In Tudor England, the growing demand for wool had a big impact on the land. The chance to make large profits from wool encouraged lords to enclose common land and turn it into pasture, mostly for sheep. This often meant villagers were forced from their homes and lost their ways of making a living. This became a major political issue for the Tudor kings and queens.

The government was worried that many of the people who lost their land would become homeless wanderers and thieves. Also, fewer people in villages meant a weaker workforce and a weaker military for the country.

From the time of Henry VII, Parliament started passing laws to stop enclosure, limit its effects, or at least fine those responsible. These "tillage acts" were passed between 1489 and 1597.

However, the people in charge of enforcing these laws were often the same people who were against them. So, the laws weren't strictly enforced. Eventually, with growing public anger against sheep farming, a law in 1533 limited the size of sheep flocks to no more than 2,400. Then, in 1549, a poll tax was put on sheep, along with a tax on homemade cloth. This made sheep farming less profitable.

In the end, it was market forces that stopped the conversion of farmland into pasture. An increase in grain prices in the second half of the 16th century made growing crops more appealing. So, while enclosures continued, the focus shifted to making better use of farmland.

Parliamentary Enclosure Acts

Historically, the idea to enclose land came from either a landowner wanting to earn more rent or a farmer wanting to improve their farm. Before the 17th century, enclosures were usually done by informal agreement.

Even when Parliament started passing laws for enclosure, the informal methods continued. The first enclosure by an Act of Parliament was in 1604 for Radipole, Dorset. Many more parliamentary Acts followed, and by the 1750s, the parliamentary system became the most common way to enclose land.

The Inclosure Act 1773 created a law that allowed land to be enclosed, while also taking away commoners' rights to access it. Even though people usually received some payment, it was often a smaller and poorer quality piece of land. Between 1604 and 1914, over 5,200 enclosure bills were passed, affecting about 6.8 million acres of land. This was roughly one-fifth of the total area of England.

Parliamentary enclosure was also used to divide and privatize common "wastes" like fens (marshy areas), heathland, downland, and moors.

Commissioners of Enclosure

The official process of enclosure involved appointing special officials called commissioners. This process often favored the person who owned the tithe (a payment, usually to the church), who had the right to appoint one enclosure commissioner for their area. Tithe-owners (often Anglican clergy) could choose to change tithe payments into a rental charge, but this would reduce their income, so many refused. However, the Tithe Act 1836 made it mandatory for tithe payments to be changed to a rent charge.

The Commissioners of Enclosure had complete power to enclose and redistribute common and open fields from around 1745 until the Inclosure Act 1845. After 1845, permanent commissioners were appointed who could approve enclosures without needing Parliament's approval for each one.

After 1899, the Board of Agriculture (which later became the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries) took over the powers of the Enclosure Commissioners.

One goal of enclosure was to improve local roads. Commissioners were allowed to replace old, winding roads and country lanes with new roads that were wider and straighter.

Enclosure Roads

England's road system had been a problem for a long time. An 1852 government report described a road between Surrey and Sussex as "very ruined and almost impossible to pass." In 1749, Horace Walpole complained that if a friend wanted good roads, they should "never go into Sussex." The problem was that country lanes were worn out, made worse by cattle moving along them.

So, the commissioners were given the power to build wide, straight roads that could handle cattle. These new roads had to be inspected by local officials to make sure they were good enough. In the late 18th century, enclosure roads were at least 60 feet wide, but from the 1790s, this was reduced to 40 feet, and later 30 feet became the normal maximum width. Straight roads from this period (1750-1850) that aren't Roman are likely enclosure roads.

Building these new roads, especially when they connected with roads in nearby areas and eventually with turnpikes (toll roads), greatly improved the country's road system.

Social and Economic Impact

Historians have debated a lot about the social and economic effects of enclosure.

An old poem, called "Stealing the Common from the Goose," shows the anger against the enclosure movement in the 18th century:

"The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common,

But lets the greater felon loose

Who steals the common from the goose."

(Part of 18th century poem by Anon.)

In 1770, Oliver Goldsmith wrote a poem called The Deserted Village, where he criticized villages losing people, common land being enclosed, and the focus on too much wealth.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, historians often felt sympathy for the cottagers (people renting small houses) and landless laborers. John and Barbara Hammond argued that "enclosure was terrible for three groups: the small farmer, the cottager, and the squatter." They said, "Before enclosure the cottager was a labourer with land; after enclosure was a labourer without land."

Some historians, like Barrington Moore Jr., saw enclosure as part of a class conflict that eventually removed the English peasantry and led to the rise of the middle class (bourgeoisie). From this view, the English Civil War greatly sped up enclosures. Parliament leaders supported the rights of landowners against the King, whose court had previously slowed down the enclosure process. By weakening the monarchy, the Civil War opened the way for landowners to gain more power in the 18th century, which led to the UK's parliamentary system.

After 1650, as grain prices rose and wool prices dropped, the focus shifted to new farming techniques, including fertilizer, new crops, and crop rotation. These greatly increased the profits of large farms. The enclosure movement likely reached its peak from 1760 to 1832. By 1832, it had mostly destroyed the traditional medieval peasant community. Peasants who no longer had land moved to towns to become factory workers. Some scholars see the enclosure movement as the beginning of capitalism.

However, other historians, like J. D. Chambers and G. E. Mingay, disagreed with the Hammonds. They suggested that the Hammonds exaggerated the negative effects. Chambers and Mingay argued that enclosure actually meant more food for the growing population, more land being farmed, and overall, more jobs in the countryside. Being able to enclose land and raise rents certainly made farming more profitable.

| Village | County | Date of enclosure |

Rise in rent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elford | Staffordshire | 1765 | "trebled" (3 times higher) |

| Lidlington | Bedfordshire | 1775 | 83% higher |

| Coney Weston | Suffolk | 1777 | Doubled (2 times higher) |

| 23 villages | Lincolnshire | before 1799 | 92% higher |

| Riseley | Bedfordshire | 1793 | 90%-157% higher |

| Milton Bryant | Bedfordshire | 1793 | 88% higher |

| Queensborough | Leicestershire | 1793 | 92%-130% higher |

| Dunton | Bedfordshire | 1797 | 113% higher |

| Enfield | Middlesex | 1803 | 33% higher |

| Wendelbury | Oxfordshire | around 1805 | 140%-167% higher |

| Source:

D. McCloskey. "The openfields of England: rent, risk and the rate of interest, 1300-1815" |

|||

Arnold Toynbee believed that the biggest change in English agriculture was the huge reduction in common land between the mid-18th and mid-19th centuries.

The main benefits of enclosure were:

- More effective crop rotation.

- Saving time by not having to travel between scattered fields.

- An end to constant arguments over boundaries and grazing rights in meadows.

Toynbee wrote: "The result was a great increase in farm produce. Landowners, having separated and combined their plots, could use any farming method they preferred. New ways of farming came in. Animal manure made the farmland richer, and grass crops on the plowed and manured land were much better than on constant pasture."

Since the late 20th century, these ideas have been questioned by new historians. Some see the Enclosure movement as destroying the traditional peasant way of life, even if it was hard. Peasants who lost their land could no longer be independent and had to become laborers. Historians and economists like M.E.Turner and D. McCloskey have looked at old data and concluded that the difference in efficiency between the open-field system and enclosure was not always so clear.

| Open Field | Enclosed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | Barley | Oats | Wheat | Barley | Oats | |

| Mean acres per parish | 309.4 | 216.0 | 181.3 | 218.9 | 158.2 | 137.3 |

| Mean produce per parish (bushels) | 5,711.5 | 5,587.0 | 6,033.1 | 4,987.1 | 5,032.2 | 5,058.2 |

| Mean yield per acre (bushels) | 18.5 | 25.9 | 33.3 | 22.8 | 31.8 | 36.8 |

| Source:

M.E.Turners paper "English Open Field and Enclosures:Retardation or Productivity Improvements". Notes: |

||||||

Social Unrest: Enclosure Riots

After the Black Death, from the 14th to 17th centuries, landowners began changing farmland into sheep pastures, supported by laws like the Statute of Merton of 1235. This led to villages losing many people. Peasants fought back with a series of revolts. In the 1381 Peasants' Revolt, enclosure was one of the smaller issues. However, in Jack Cade's rebellion of 1450, land rights were a major demand. By the time of Kett's Rebellion in 1549, enclosure was a main reason for the uprising, as it was in the Captain Pouch revolts of 1604-1607. During these revolts, terms like "leveller" and "digger" appeared, referring to those who tore down the ditches and fences built by enclosers.

D. C. Coleman wrote that "many troubles arose over the loss of common rights," causing anger and hardship from various issues, including "the loss of ancient rights in the woodlands to cut underwood, to run pigs."

Protests against enclosure weren't just in the countryside. Enclosure riots also happened in towns and cities across England in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. This urban unrest spread across the whole country, from York in the north to Southampton in the south, and from Gloucester in the west to Colchester in the east. The city rioters weren't always farm workers; they included skilled workers like butchers, shoemakers, plumbers, clothmakers, millers, weavers, glovers, and barbers.

Midland Revolt

In May and June 1607, villages like Cotesbach (Leicestershire), Ladbroke (Warwickshire), and Haselbech (Northamptonshire) saw protests against enclosures and depopulation. This rioting became known as the Midland Revolt and had a lot of support from local people. It was led by John Reynolds, also known as 'Captain Pouch'. He was thought to be a traveling peddler or tinker from Desborough, Northamptonshire. He told the protesters he had permission from the King and from Heaven to destroy enclosures. He promised to protect them with a pouch he carried, saying it would keep them safe (after he was caught, his pouch was opened, and it only contained a piece of moldy cheese). A curfew was put in place in Leicester because officials feared citizens would leave the city to join the riots. A gibbet (a gallows) was set up in Leicester as a warning, but citizens pulled it down.

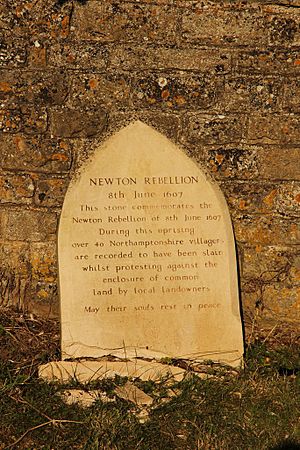

Newton Rebellion: 8 June 1607

The Newton Rebellion was one of the last times that ordinary English commoners (not miners) and the upper class fought openly with weapons. Things became very tense in early June. King James I issued a public order and told his local officials in Northamptonshire to stop the riots. Records show that women and children were part of the protest. Over a thousand people gathered at Newton, near Kettering. They pulled down hedges and filled in ditches to protest against the enclosures made by Thomas Tresham.

The Tresham family was disliked for enclosing so much land. The Treshams at Newton and their more famous Roman Catholic cousins at nearby Rushton (the family of Francis Tresham, who had been involved in the Gunpowder Plot two years earlier) were very unpopular. Sir Thomas Tresham of Rushton was called 'the most hateful man' in Northamptonshire. The old Roman Catholic Tresham family had long argued with the rising Puritan Montagu family (of Boughton) over land. Now, Tresham of Newton was enclosing common land – The Brand Common – which had been part of Rockingham Forest.

Edward Montagu, one of the local officials, had spoken against enclosure in Parliament years earlier. But now, the king put him in a position where he had to defend the Treshams. The local armed groups and militia refused to join, so the landowners had to use their own servants to stop the rioters on June 8, 1607. The king's order was read twice. The rioters kept going, though some ran away after the second reading. The gentry and their forces attacked. A battle followed, where 40–50 people were killed. The leaders were hanged and cut into pieces. A memorial stone to those killed stands at the former church of St Faith, Newton, Northamptonshire.

The Tresham family's power declined soon after 1607. The Montagu family, through marriage, later became the Dukes of Buccleuch, greatly increasing their wealth.

Western Rising 1630–32 and Forest Enclosure

Even though royal forests weren't technically common lands, people had used them as such since at least the 1500s. By the 1600s, when Stuart kings looked for new ways to make money from their lands, they had to offer some payment to those using the forests as commons when the forests were divided and enclosed. Most of this "disafforestation" (removing forest status) happened between 1629 and 1640, during Charles I of England's time ruling without Parliament. Most of the people who benefited were royal courtiers, who paid large sums to enclose and rent out the forests. Those who lost their common rights, especially recent cottagers and those outside of manor lands, received little or no payment, and they rioted in response.

Images for kids

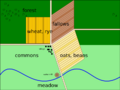

-

A possible map of a medieval English manor. The 'common pasture' is in the north-east, shaded green.

-

The three-field system with ridge and furrow fields.

-

Old hedges show where straight field boundaries were created by the 1768 Parliamentary Act of Enclosure of Boldron Moor, County Durham.

-

A parliamentary enclosure road near Lazonby in Cumbria. These roads were made as straight as possible and much wider than a cart, to reduce damage from driving sheep and cattle.

See also

In Spanish: Cercamiento para niños

In Spanish: Cercamiento para niños

- British Agricultural Revolution

- the Diggers

- Gerrard Winstanley

- Levellers

- Highland Clearances

- Lowland Clearances

- Primitive accumulation of capital

- Swing Riots

- Abandoned village

- Accumulation by dispossession

- Tragedy of the commons

- Digital enclosure

In other countries