Infantry in the American Civil War facts for kids

The infantry in the American Civil War were the foot soldiers who did most of the fighting. They used mostly small guns and were involved in the toughest battles across the United States.

Historians have long discussed how fighting methods changed between 1861 and 1865. Some believe that generals stuck to old ways of fighting, like those from the Napoleonic Wars. This meant soldiers stood in straight lines in open fields. But new, more accurate rifle muskets made these old ways very dangerous. Many think the longer battles in 1864 showed how much new technology changed warfare.

However, some experts now disagree. They say that the training of Civil War armies was very important. They also point out that big, overwhelming victories were rare throughout history, not just in this war. Some argue that rifle muskets did not completely change land warfare. This was because soldiers often didn't train enough with their guns. Also, the smoke from black powder made it hard to see far.

This discussion helps us understand what it was like to be a soldier. It also helps us see how modern the Civil War truly was. Some historians say the war was a mix of the Industrial Revolution (new machines) and the French Revolution (new ideas about people). This mix allowed both sides to gather huge armies and fight over long distances. The war also saw other new technologies like military balloons, repeating rifles, the telegraph, and railroads.

Contents

Starting the War

When the war began, the entire United States Army had only 16,367 men. Most of these were infantry soldiers. Some had fought in the Mexican–American War or against Native Americans in the West. But most soldiers spent their time guarding places or doing daily tasks. Most infantry officers had gone to military schools like the United States Military Academy.

Some states, like New York, had already formed their own soldier groups called militias. These were sometimes for fighting Native Americans. But by 1861, they were mostly for social gatherings and parades. These groups were more common in the South. Hundreds of small local militias existed there to guard against slave uprisings.

After Abraham Lincoln was elected President, eleven Southern states left the Union. By early 1861, thousands of Southern men joined new companies. These quickly formed into regiments, brigades, and small armies, creating the Confederate States Army. President Lincoln asked for 75,000 volunteers to stop the rebellion. Later, he asked for even more. The Northern states responded. These forces became known as the Volunteer Army. Over 1,700 state volunteer regiments were formed for the Union Army during the war. Infantry soldiers made up more than 80% of these forces.

How Armies Were Organized

An infantry regiment in the early Civil War usually had 10 companies. Each company was supposed to have 100 men, led by a captain and lieutenants. The main officers of a regiment were a colonel (the commander), a lieutenant colonel, and at least one major.

As the war went on, many soldiers were lost to disease, battles, or leaving the army. By the middle of the war, most regiments had only 300–400 men. State governments paid volunteer regiments. At first, officers were often chosen by popular vote or by state governors. As the war continued, the War Department and higher officers started choosing regimental leaders. Regimental officers usually picked the non-commissioned officers (NCOs) based on how well they performed.

Large regiments were often divided into two or more battalions. The lieutenant colonel and major(s) would lead these battalions. A regiment might also be split into left and right "wings" for training. The regimental commander was in charge of all these officers. He used messengers to send and receive orders.

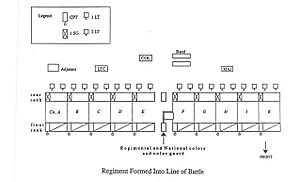

In battle, the color guard was usually in the middle of the regiment. This group of five to eight men carried and protected the regimental or national flags. Most Union regiments carried both flags. Confederate regiments usually only had a national flag.

Individual regiments (usually three to five) were grouped into a larger unit called a brigade. This became the main unit for battlefield movements. A brigade was usually led by a brigadier general or a senior colonel. Two to four brigades typically formed a division, led by a major general. Several divisions made up a corps. Multiple corps together formed an army. Confederate armies were often led by a lieutenant general or full general. Union armies were led by a major general.

Here is how the infantry units were typically organized for both sides:

Confederate Army Units

| Unit Type | Fewest | Most | Average | Most Common |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corps per army | 1 | 4 | 2.74 | 2 |

| Divisions per corps | 2 | 7 | 3.10 | 3 |

| Brigades per division | 2 | 7 | 3.62 | 4 |

| Regiments per brigade | 2 | 20 | 4.71 | 5 |

Union Army Units

| Unit Type | Fewest | Most | Average | Most Common |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corps per army | 1 | 8 | 3.71 | 3 |

| Divisions per corps | 2 | 6 | 2.91 | 3 |

| Brigades per division | 2 | 5 | 2.80 | 3 |

| Regiments per brigade | 2 | 12 | 4.73 | 4 |

Battle Tactics

Both Union and Confederate armies used a changed version of linear tactics. These tactics came from the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. They were designed for smoothbore muskets, which were not very accurate. These guns were only good at 40 to 60 yards. So, armies focused on firing many shots at once (called volley fire) to hurt the enemy. American commanders learned these tactics from manuals. Key manuals included those by Winfield Scott (1835), William J. Hardee (1855), and Silas Casey (1862).

However, the Civil War saw many rifled muskets used. These guns, using the Minié ball, could hit targets accurately up to 500 yards away. People at the time thought this would give defenders a big advantage. They also expected more deaths in battles. After the war, many soldiers complained that generals still used old Napoleonic tactics. They said frontal attacks in tight groups caused too many deaths. Some historians later agreed, saying the rifled musket made frontal attacks useless and led to trench warfare.

More recently, historians have looked at this idea again. They found that even with better rifles, most fighting happened at short distances, similar to smoothbore muskets. The number of deaths was also not much different from earlier wars. Several reasons explain this. Allen Guelzo points out two problems with the rifled musket. First, it still used black powder. Firing these guns created huge clouds of smoke. This smoke could reduce visibility to "less than fifty paces," making it impossible to aim far. Second, the Minié ball had a curved path. This meant a shooter needed a lot of training to hit targets at long range.

Adding to these problems, soldiers in both armies rarely practiced shooting. Officers were told to train their men, but no money was given for it. The lack of training was clear. For example, 40 men from the 5th Connecticut shot at a 15-foot barn from 100 yards away. Only four shots hit the barn, and only one was high enough to hit a person. Another soldier from the 1st South Carolina said that during a fierce fight at 100 yards, most shots hit pinecones and needles in the trees above them. Highly trained sharpshooters could use rifled muskets well. But for most infantry, poor training and battle stress meant they would "simply raise his rifle to the horizontal, and fire without aiming."

Historian Earl J. Hess argues that, given these factors, using linear tactics in the Civil War was still smart. The most successful units were those who knew these tactics best. An increase in how many shots could be fired, rather than how far, might have needed new tactics. But fast-loading breechloaders and repeating firearms were not widely available until after the war.

The main idea of these tactics was to arrange soldiers in ranks (rows) and files (columns). This formed a regiment into a line of battle or a column. The line was the main way to fight because it let soldiers fire a full volley at the enemy. A line usually had companies in two rows, with soldiers close enough to touch elbows. The regimental flags in the center and guides on the ends kept the line straight. Soldiers called "file closers" stood behind the line to keep order and stop desertions. A standard 475-man regiment in a line would cover about 140 yards.

The column was mostly used for moving. A simple column had companies stacked one behind another. A more common "double column" had two stacks of companies next to each other. This made the formation shorter and wider. Infantry squares were rarely used. They were hard to form and usually not needed in Civil War battles.

Skirmishers were very important. Hess believes their use reached its peak during the Civil War. A company would split into two groups (platoons). One platoon formed the skirmish line, and the other stayed 150 paces behind as a backup. Skirmishers worked in groups of four, called "comrades in battle." They were spaced five paces apart, with 20 to 40 paces between each group. Usually, two companies formed a skirmish line for a regiment. On a larger scale, a regiment would form a skirmish line for a brigade. Skirmish lines were like a more advanced battle line. They needed more skill and bravery from the soldiers. They could protect a defensive line by bothering approaching enemies. They could also check the enemy's strength before an attack or hide an attacking force. Some regiments were better at skirmishing than others, but most were good enough.

Infantry attacks often involved multiple waves of battle lines attacking the enemy. Instead of one commander leading all lines, commanders were given specific areas of the battlefield. They would then form their own regiments into successive lines. This allowed for better control. Successive lines were best spaced a few hundred yards apart. This kept them far enough to avoid the same enemy fire but close enough to help each other. Using successive lines also meant knowing how to move one line through another without causing confusion. It was also common to organize successive lines into an echelon formation. This was done to protect an exposed side or to go around an enemy line.

Weapons and Gear

Many generals were trained when short-range smoothbore muskets, like the Springfield Model 1842, were common. So, they often didn't fully understand the power of new weapons. These included the 1861 Springfield rifled musket and similar rifles. These new rifles had longer range and were more powerful than older guns. Their barrels had rifled grooves that made them more accurate. They fired a .58 caliber Minié ball (a small, cone-shaped bullet). This rifle could kill at 600 yards and seriously wound a man beyond 1,000 yards. Older muskets from the American Revolutionary War and Napoleonic Wars were only effective at about 100 yards.

However, as mentioned, historians like Guelzo say these benefits were often lost. This was because it was hard to see on a Civil War battlefield. Battles usually happened with large lines of infantry at about 100 yards. Soldiers simply couldn't see the enemy at longer distances. Neither side used smokeless powder. In many battles, unless there was a strong wind, the first shots from each side would hide the enemy line in gunsmoke for a long time. So, the main plan for both sides was to get close to the enemy and fire at very short range for the best effect.

Even smoothbore muskets got better. Soldiers learned to load them with a mix of small pellets and a single round ball. This made their shots spread out like a shotgun. Other infantrymen went into battle with shotguns, pistols, knives, and other weapons. Very early in the war, a few companies even had pikes. But by the end of 1862, most infantrymen had rifles. Many of these were imported from Great Britain, Belgium, and other European countries.

A typical Union soldier carried his musket, a cap box for percussion caps, a cartridge box for bullets, a canteen, a knapsack, and other items. Many Southern soldiers, however, carried their things in a blanket roll. This was worn around the shoulder and tied at the waist. They might have a wooden canteen, a linen or cotton bag for food, and a knife.

James Gall, from the United States Sanitary Commission, described a typical Confederate infantryman. He saw soldiers from Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early's army in York, Pennsylvania, in June 1863.

Physically, the men looked about equal to the generality of our own troops, and there were fewer boys among them. Their dress was a wretched mixture of all cuts and colors. There was not the slightest attempt at uniformity in this respect. Every man seemed to have put on whatever he could get hold of, without regard to shape or color. I noticed a pretty large sprinkling of blue pants among them, some of those, doubtless, that were left by Milroy at Winchester. Their shoes, as a general thing, were poor; some of the men were entirely barefooted. Their equipments were light, as compared with those of our men. They consisted of a thin woolen blanket, coiled up and slung from the shoulder in the form of a sash, a haversack swung from the opposite shoulder, and a cartridge-box. The whole cannot weigh more than twelve or fourteen pounds. Is it strange, then, that with such light loads, they should be able to make longer and more rapid marches than our men? The marching of the men was irregular and careless, their arms were rusty and ill kept. Their whole appearance was greatly inferior to that of our soldiers... There were not tents for the men, and but few for the officers... Everything that will trammel or impede the movement of the army is discarded, no matter what the consequences may be to the men... In speaking of our soldiers, the same officer remarked: 'They are too well fed, too well clothed, and have far too much to carry.' That our men are too well fed, I do not believe, neither that they are too well clothed; that they have too much to carry, I can very well believe, after witnessing the march of the Army of the Potomac to Chancellorsville. Each man had eight days' rations to carry, besides sixty rounds of ammunition, musket, woollen blanket, rubber blanket, overcoat, extra shirt, drawers, socks, and shelter tent, amounting in all to about sixty pounds. Think of men, and boys too, staggering along under such a load, at the rate of fifteen to twenty miles a day.

Fast-Firing Weapons

Thousands of repeating rifles and breechloaders were given to Union cavalry. These included the 7-shot Spencer and 15-shot Henry models. But not much money was spent to give Union infantry the same weapons. Some volunteer regiments got extra money from their state or a rich commander. Otherwise, infantry soldiers often bought their own fast-firing weapons. These were usually used by skirmishers.

President Lincoln liked these new weapons. But some senior Union officers did not want repeating rifles for the infantry. They worried about the high cost and how much ammunition they would use. They also worried about the extra smoke these guns made on the battlefield. The most important person against these new rifles was 67-year-old General James Ripley. He was the US Army's chief of weapons. He strongly opposed what he called "these newfangled gimcracks." He believed they would make soldiers "waste ammunition." He also argued that the quartermaster corps could not supply enough ammunition for an army with repeating rifles.

One special case was Colonel John T. Wilder's mounted infantry, called the "Lightning Brigade." Colonel Wilder was a rich engineer and factory owner. He took out a bank loan to buy 1,400 Spencer rifles for his soldiers. The soldiers really liked these magazine-fed weapons. Most agreed to have money taken from their monthly pay to help pay for them.

During the Battle of Hoover's Gap, Wilder's brigade of 4,000 men had Spencer rifles and strong defenses. They held off 22,000 attacking Confederates. They caused 287 Confederate deaths for only 27 of their own. Even more amazing, during the second day of the Battle of Chickamauga, his Spencer-armed brigade counterattacked. They faced a much larger Confederate division that was taking over the Union's right side. Thanks to the Lightning Brigade's powerful guns, they pushed back the Confederates. They caused over 500 Confederate deaths while losing only 53 men.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |