Insular Celts facts for kids

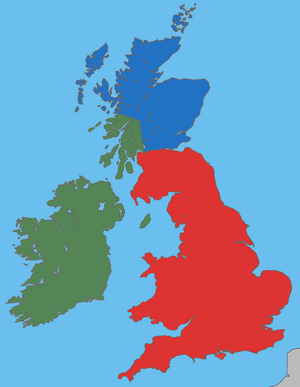

The Insular Celts were groups of people who lived in the British Isles and Brittany (a part of France). They spoke languages from the Insular Celtic languages family. This term mostly describes the Celtic people in these islands up until the early Middle Ages. This includes the time of the Iron Age in Britain and Ireland, and the periods of Roman Britain and Sub-Roman Britain. The main groups of Insular Celts were the Celtic Britons, the Picts, and the Gaels.

These Insular Celtic languages spread across the islands during the Bronze Age or early Iron Age. They are divided into two main types: Brittonic in the east and Goidelic in the west. While we have records of other Celtic languages from mainland Europe as far back as 600 BC, the Insular Celtic languages only started to be written down around 1 AD. The Insular Celts followed an Ancient Celtic religion led by wise people called druids. Some tribes in southern Britain had strong connections with mainland Europe, especially Gaul (modern France) and Belgica (modern Belgium). They even made their own coins.

The mighty Roman Empire took over most of Britain in the 1st century AD. A new Romano-British culture grew in the southeast, mixing Roman and British ways. But the Britons and Picts in the north, and the Gaels in Ireland, stayed outside the Roman Empire. When Roman rule ended in the 400s, many Anglo-Saxons settled in eastern and southern Britain. Some Gaels also settled on Britain's western coast. Around this time, some Britons moved to the Armorican peninsula (now Brittany), where their culture became very important. Meanwhile, much of northern Britain (which became Scotland) became Gaelic.

By the 10th century, the Insular Celts had changed and become different groups. These included the Brittonic-speaking Welsh (in Wales), Cornish (in Cornwall), Bretons (in Brittany), and Cumbrians (in northern England). The Goidelic-speaking groups were the Irish (in Ireland), Scots (in Scotland), and Manx (on the Isle of Man).

Contents

How Celts Settled Britain and Ireland

Archaeological Discoveries

Archaeologists have studied how Celtic culture arrived in Britain and Ireland. In the past, some thought that large groups of Celtic invaders came to the islands. For example, a scholar named T. F. O'Rahilly suggested in 1946 that four separate waves of Celtic invaders came to Ireland during the Iron Age.

However, archaeologists found little evidence for these big invasions. Instead, newer research suggests that Celtic culture and language might have grown gradually. This means the people already living there slowly adopted Celtic ways and language. It wasn't necessarily about new people invading, but more about ideas and culture spreading.

In the 1970s, archaeologist Colin Burgess suggested a "continuity model." He believed that Celtic culture in Great Britain "emerged" from the people already living there, rather than from invaders. He thought the Celts were descendants of, or influenced by, people like the Amesbury Archer, who had connections to mainland Europe.

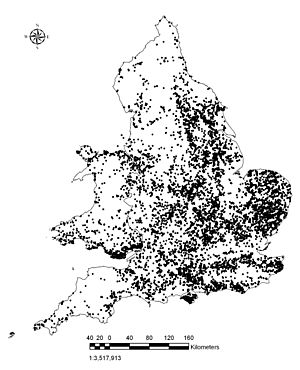

Archaeological finds show that culture in Britain stayed quite similar throughout the 1st millennium BC. However, some parts of the "Celtic" La Tène culture from the 4th century BC were adopted. There is also evidence of chariot burials in England starting around 300 BC, mostly in an area linked to the Parisii tribe.

Language Clues

Some old place names, like the rivers Clyde, Tamar, and Thames, might come from languages spoken before Celtic languages arrived.

Experts believe that by about 600 BC, most people in Ireland and Britain were speaking Celtic languages. Some studies suggest Insular Celtic languages might be even older, perhaps around 2,900 years old.

It's not fully clear if there was ever one "Common Insular Celtic" language that later split. Another idea is that different Celtic groups settled in Ireland and Britain, speaking different Celtic dialects from the start. However, many experts now think there was likely a single "Insular Celtic" language that later divided into Goidelic and Brittonic.

This idea suggests that early Celts came to both Great Britain and Ireland in one wave. But they soon split into two separate groups, one in Ireland and one in Great Britain. This would mean the split between Goidelic and Brittonic happened around 500 BC. Another idea is that early Celts first came to Britain, and then later some moved to Ireland.

The Goidelic branch of languages developed into Primitive Irish, Old Irish, and Middle Irish. Later, as the Gaels expanded, it split into the modern Gaelic languages: Modern Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx.

On the other hand, Common Brittonic split into two branches: British and Pritenic. This happened because of the Roman invasion of Britain in the 1st century. By the 8th century, Pritenic had become the Pictish language (which died out around the 9th century). British had split into Old Welsh and Old Cornish.

Genetic Evidence

Studies of human genetics help us understand ancient migrations. For example, the spread of the Bell Beaker culture to the British Isles around 2500 BC involved a lot of migration. About 90% of the local gene pool was replaced within a few hundred years by people with genes from the steppes (grasslands) of Europe.

A 2003 study found that genetic markers common in Gaelic names in Ireland and Scotland are also found in parts of west Wales and England. These markers are similar to those of the Basque people in Spain and France, and quite different from northern Germanic people. This suggested a large genetic link to people living in the area before the Celts arrived. The study suggested that Celtic culture and language might have spread through cultural contact (ideas spreading) rather than "mass invasions."

Later genetic studies in 2006, like those by Bryan Sykes and Stephen Oppenheimer, also found evidence for migrations from the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) during the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) and Neolithic (New Stone Age) periods. But they found very little evidence for large migrations during the Iron Age.

However, a big study in 2021 found evidence of a migration into southern Britain during the Bronze Age, between 1300 and 800 BC. These newcomers were genetically similar to ancient people from Gaul. Their genetic markers quickly spread through southern Britain, but not northern Britain, between 1000 and 875 BC. Scientists think this migration could be how early Celtic languages spread into Britain. Since there was much less migration during the Iron Age, it's likely Celtic languages arrived before then. Some experts, like Barry Cunliffe, suggest that a branch of Celtic was already spoken in Britain, and this Bronze Age migration introduced the Brittonic branch.

Life in Iron Age Britain

The British Iron Age is the name for a period in the archaeology of Great Britain. It usually doesn't include prehistoric Ireland, which had its own Iron Age culture. The Irish period is called the Irish Iron Age.

In Britain, the Iron Age began when people started using iron for tools and weapons. It ended when the southern half of the island became Roman. The Roman way of life that followed is called Roman Britain.

The only surviving description of the Iron Age people in the British Isles comes from Pytheas, a Greek explorer who traveled there around 325 BC. The earliest names of tribes we know about are from the 1st century AD. These names come from writers like Ptolemy and Caesar, and sometimes from coins. They tell us about the tribes living there when the Romans arrived.

Roman Times and Early Middle Ages

Roman Britain lasted for about 400 years, from the mid-1st century to the mid-5th century. During this time, a mixed Romano-British culture formed in southern Great Britain. This was similar in some ways to the Gallo-Roman culture in Gaul (France). However, in Gaul, the Roman influence was so strong that the local Gaulish language was almost completely replaced by Vulgar Latin (the common Latin spoken by people). This didn't happen in Roman Britain. Even though a form of British Latin was probably spoken in Roman towns, it wasn't strong enough to replace the British dialects spoken across the country. Some small groups of Latin-speaking people might have remained in Britain as late as the 8th century.

Northern Britain (north of Hadrian's Wall) and Ireland mostly stayed in the prehistoric period until after the Romans left. Ireland's "protohistoric" period began around 400 AD. This was due to ideas spreading from Roman Britain, like writing (ogham, the earliest form of Primitive Irish) and Christianity. The people north of Roman Britain are often called Caledonians. We don't know much about them, except that they were a constant military threat to the Roman border.

With the Anglo-Saxon invasions and settlements in the 5th and 6th centuries, the British languages slowly became limited to the western parts of the island, in what is now Wales and Cornwall. This change might not have been a huge migration of people replacing everyone. Instead, it could have been a new ruling class arriving and making their culture and language dominant. A similar thing happened when the Gaels took over the areas where Pictish was spoken in Northern Britain. There seems to have been a time in the 6th century when British and Saxon cultures mixed. Some British rulers had Saxon names, and some Saxon rulers had British names.

By the end of the Dark Ages, around the 8th century, the Insular Celtic peoples had become the ancestors of the Gaelic and Welsh cultures of Gaelic Ireland and Medieval Wales.

More to Explore

- Insular art - This art style includes both Anglo-Saxon art and Celtic art from the British Isles after the Roman period.

- Celtic place names: Insular Celtic

- British place names: Celtic

- Goidelic substrate hypothesis

- Insular Celtic languages

- Iron Age Britain

- Genetic history of the British Isles

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |