International Brigades facts for kids

Quick facts for kids International Brigades |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Active | 18 September 1936 – 23 September 1938 |

| Country | Albania, France, Italy, Germany, Poland, United States, Ireland, Yugoslavia, United Kingdom, Belgium, Canada, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Mexico, Argentina, Netherlands, and others... |

| Allegiance |

|

| Type | Infantry |

| Role | Paramilitary |

| Size | between 40,000 and 59,000 |

| Garrison/HQ | Albacete |

| Motto(s) |

|

| Engagements | Spanish Civil War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

|

| Insignia | |

| Flag | |

The International Brigades (Spanish: Brigadas Internacionales) were special military groups. They were formed by the Communist International, a global organization that promoted communism. Their main goal was to help the government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. These brigades existed for about two years, from 1936 to 1938.

Around 40,000 to 59,000 people from many different countries joined the International Brigades. Sadly, about 10,000 of them died fighting. The main base for the brigades was in Albacete, Spain. They fought in many important battles, including Madrid, Jarama, Guadalajara, and the Ebro. Many of these battles were very difficult and ended in defeat.

The Soviet Union strongly supported the International Brigades. They sent weapons, supplies, and military advisors to help the Spanish Republic. At the same time, countries like Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany were helping the other side, the Nationalists. Many volunteers came from France, Italy, and Germany. A large number of Jewish people also joined the brigades, especially from the United States, Poland, and France.

Not everyone who wanted to fight against the Nationalists joined the Brigades. Some volunteers, who did not agree with the Soviet Union's ideas, joined other groups like the POUM or anarcho-syndicalist groups.

Contents

Forming the Brigades: How Volunteers Joined

The idea of having foreign volunteers fight in Spain came from the Soviet Union in September 1936. Communist parties in different countries helped find people to join. Volunteers who were not communists were carefully checked before they could join.

The Italian and French Communist Parties were among the first to organize groups of fighters. The Soviet military also helped, as they had experience with international volunteers from their own past wars. At first, the Spanish government leader, Largo Caballero, was against the idea. But after some early losses in the war, he changed his mind.

Paris, France, became the main place for recruiting volunteers. In October 1936, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin wrote that helping Spain was important for all "progressive humanity." This encouraged many people to join anti-fascist groups.

Volunteers traveled to Spain by train or ship from France. They were then sent to the main base in Albacete. Many people joined because they believed they were fighting for democracy or a revolution in their own countries. Some were unemployed workers, and others were adventurers. About 500 communists who had been exiled to Russia also came to Spain. They were experienced military leaders from World War I.

Anarchists, another group fighting in Spain, were at first unsure about the communist volunteers. But they eventually allowed them to pass through the borders. A group of about 500 volunteers, mostly French, arrived in Albacete in October 1936. They met other international fighters who were already there.

In May 1937, a Spanish ship called Ciudad de Barcelona was carrying 200-250 volunteers to Spain. It was hit by a Nationalist submarine and sank. Up to 65 volunteers may have drowned.

Albacete quickly became the main headquarters and supply center for the International Brigades. It was managed by three important leaders from the Communist International: André Marty, Luigi Longo, and Giuseppe Di Vittorio.

Many Jewish volunteers were part of the brigades. About a quarter of all volunteers were Jewish. A special Jewish company was formed within the Polish battalion. It was named after Naftali Botwin, a young Jewish communist.

The French Communist Party provided uniforms for the brigades. The fighters were organized into "mixed brigades," which were the basic units of the Spanish Republican Army. Discipline was very strict. For several weeks, the brigades stayed at their base for intense military training.

Fighting in Spain: Key Battles

First Fights: The Siege of Madrid

The Battle of Madrid was a big success for the Spanish Republic. It stopped Francisco Franco's forces from winning the war quickly. The International Brigades played an important part in this victory. Their role was sometimes made to seem bigger by propaganda, but they certainly helped. Out of 40,000 Republican troops in Madrid, fewer than 3,000 were foreign fighters.

Even though the International Brigades did not win the battle alone, their determined fighting set a good example. They also boosted the spirits of the people in Madrid by showing that other countries cared about their fight. Many older members of the brigades had valuable combat experience from World War I.

One important place in Madrid was the Casa de Campo. Nationalist troops, led by General José Enrique Varela, were stopped there by Spanish Republican Army brigades.

On November 9, 1936, the XI International Brigade took up positions at Casa de Campo. This brigade had 1,900 men from different battalions. Their commander, General Kléber, launched an attack on the Nationalist positions. The fighting lasted all night and into the next morning. The Nationalist troops had to retreat, and the XIth Brigade lost a third of its fighters.

On November 13, the XII International Brigade, with 1,550 men, attacked Nationalist positions. This attack failed because of language problems, communication issues, and not enough support.

On November 19, Nationalist troops, including Moroccan and Spanish Foreign Legionnaires, captured part of the University City. The 11th Brigade was sent to push them out. The battle was very bloody, with artillery, bombs, and close-up fights. The anarchist leader Buenaventura Durruti was shot there and died the next day. The fighting in the university continued until most of it was under Nationalist control. Both sides then built trenches, showing that a direct attack on Madrid would be too costly.

In December 1936, Nationalist troops tried to surround Madrid. The Republicans sent in a Soviet armored unit and both the XI and XII International Brigades. They stopped the Nationalist advance after fierce fighting.

The Republic then launched an attack on the Córdoba front. The battle ended in a tie. Two poets, Ralph Winston Fox and John Cornford, were killed. The Nationalists eventually took a hydroelectric station.

Further Nationalist attempts to surround Madrid after Christmas also failed, but there was very violent fighting. By January 15, 1937, both sides had built trenches, leading to a stalemate. Madrid was not taken by the Nationalists until the very end of the war in March 1939.

Battle of Jarama: A Tough Fight

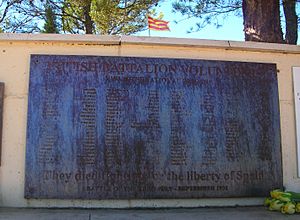

On February 6, 1937, the Nationalists attacked a road south of Madrid. They quickly moved towards the town of Ciempozuelos, which was held by the XV International Brigade. This brigade included the British Battalion, the Dimitrov Battalion, the Sixth February Battalion, the Canadian Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, and the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. An Irish unit, the Connolly Column, also fought. Battalions often had people from many different countries.

On February 11, 1937, a Nationalist brigade launched a surprise attack. They quietly killed the guards of the André Marty Battalion and crossed the Jarama river. The Garibaldi Battalion stopped their advance with heavy fire.

On February 12, the British Battalion faced a very strong attack. They were under heavy fire for seven hours. By the end of the day, only 225 out of 600 members of the British battalion were left. One company was tricked when Nationalists advanced among them, singing a famous song.

On February 17, the Republican Army fought back. On February 23 and 27, the International Brigades attacked, but without much success. The Lincoln Battalion suffered many losses, with 120 killed and 175 wounded. The Irish poet Charles Donnelly was among the dead.

Both sides had many casualties, and the battle ended in a tie. Both sides then dug in and built complex trench systems. On February 22, 1937, a ban on foreign volunteers, set by the League of Nations, officially began.

Battle of Guadalajara: Italian vs. Italian

After failing at Jarama, the Nationalists tried another attack on Madrid from the northeast. Their target was Guadalajara, about 50 kilometers from Madrid. The entire Italian army corps, with 35,000 men, 80 tanks, and 200 artillery guns, was used. This was because Italian leader Benito Mussolini wanted Italy to get credit for the victory.

On March 9, 1937, the Italians broke through the Republican lines. The situation looked bad for the Republicans. But a strong group of Republican units, including the XI and XII International Brigades, quickly gathered.

On March 10, the Nationalists moved closer. By noon, the Garibaldi Battalion counterattacked. There was some confusion because both sides spoke Italian. Scouts from both sides even exchanged information without realizing they were enemies! The Republican lines moved forward and met the XI International Brigade.

On March 11, the Nationalist army broke the Republican front. The Thälmann Battalion suffered heavy losses but managed to hold a key road. The Garibaldi Battalion also held its ground. On March 12, Republican planes and tanks attacked. The Thälmann Battalion attacked a town with bayonets and took it back, capturing many prisoners.

Other Important Battles

The International Brigades also fought in the Battle of Teruel in January 1938. The 35th International Division suffered greatly from air attacks and a lack of food, warm clothes, and ammunition. The XIV International Brigade fought in the Battle of Ebro in July 1938. This was the last major attack by the Republican side in the war.

Casualties: The Cost of War

It's hard to know exactly how many brigadiers died. Some reports say around 4,575 were killed, while others suggest 3,615 or even 5,000. Historians also have different numbers, ranging from 6,100 to 15,000 deaths. These numbers include those killed in action, those who died later from wounds, or those executed as prisoners of war. They don't include those who died from accidents or illness.

The total number of casualties, including killed, missing, and wounded, is estimated at about 48,909. However, this number might include people who were wounded multiple times.

The percentage of fighters killed compared to the total number of volunteers also varies. Some sources say 8.3%, while others claim up to 33%. For comparison, in other units during the war, about 7% of all soldiers were killed in action.

The death rates for different countries' volunteers also varied greatly. For example, estimates for French volunteers range from 12% to 18% killed, while for Poles, it could be between 30% and 62%.

Disbanding the Brigades

In October 1938, during the Battle of the Ebro, a group called the Non-Intervention Committee asked for the International Brigades to leave Spain. The Spanish government announced this decision in September 1938. This was a hopeful attempt to get the Nationalists' foreign supporters to leave too. It was also hoped that countries like France and Britain would stop their arms embargo (a ban on selling weapons) to the Republic.

By this time, about 10,000 foreign volunteers were still fighting for the Republic. The Nationalists had about 50,000 foreign soldiers, plus 30,000 Moroccans. About half of the International Brigadiers were exiles or refugees from countries with harsh governments, like Nazi Germany or Fascist Italy. These people could not safely go home. Some were given Spanish citizenship and joined Spanish army units. The rest were sent back to their home countries. Some volunteers, like those from Belgium and the Netherlands, lost their citizenship for serving in a foreign army.

Who Joined: The Brigades' Makeup

Overview of Volunteers

The first brigades were mostly made up of volunteers from France, Belgium, Italy, and Germany. Many Polish miners from France and Belgium also joined. The XIth, XIIth, and XIIIth were the first brigades formed. Later, the XIVth and XVth Brigades were created, mixing experienced soldiers with new volunteers.

About 32,000 foreigners volunteered to help the Spanish Republic. Most of them joined the International Brigades. Many had fought in World War I. Their early fights in 1936 during the Siege of Madrid showed how valuable they were for fighting and for spreading their message.

Most international volunteers were socialists, communists, or people who accepted communist leadership. Many were also Jewish. Some were involved in fighting against other leftist groups in Barcelona in May 1937. These groups, like the POUM and anarchist CNT, had strong support in Catalonia.

To make communication easier, battalions usually grouped people of the same nationality or language. Battalions were often named after inspiring people or events. Later in the war, military rules became stricter, and learning Spanish became required. In September 1937, the International Brigades officially became part of the Spanish Foreign Legion.

Battalions from Different Countries

Here are some of the battalions and where their volunteers came from:

- Abraham Lincoln Battalion: From the United States and Canada, with some British, Cypriots, and Chileans.

- Connolly Column: A mostly Irish group that fought with the Lincoln Battalion.

- Mickiewicz Battalion: Mostly Polish.

- André Marty Battalion: Mostly French and Belgian.

- British Battalion: Mainly British, but also from Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Cyprus.

- Dimitrov Battalion: Greek, Yugoslav, Bulgarian, Czechoslovakian, Hungarian, and Romanian.

- Dabrowski Battalion: Mostly Polish and Hungarian, also Czechoslovak, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, and Palestinian Jews.

- Edgar André Battalion: Mostly German, also Austrian, Yugoslav, Bulgarian, Albanian, Romanian, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, and Dutch.

- Garibaldi Battalion: Mostly Italian and Spanish, but also some Albanians.

- Mackenzie–Papineau Battalion: The "Mac-Paps," mostly Canadian.

- Palafox Battalion: Yugoslav, Polish, Czechoslovakian, Hungarian, Jewish, and French.

- Naftali Botwin Company: A Jewish unit formed within the Palafox Battalion.

- Rakosi Battalion: Mainly Hungarian, also Czechoslovaks, Ukrainians, Poles, Chinese, Mongolians, and Palestinian Jews.

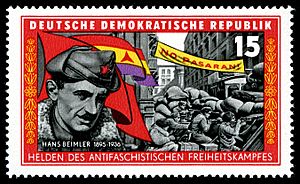

- Thälmann Battalion: Mostly German, named after German communist leader Ernst Thälmann.

- Chapaev Battalion: Made up of 21 different nationalities.

Volunteers by Country

| Country | Estimate | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 8,962–9,000 | ||

| 3,000–3,350 | ||

| 3,000–5,000 | This includes Germans and Austrians. | |

| About 1,400 Austrians are named in documents. Austria was later joined with Germany in 1938. | ||

| 500–5,000 | Most historians estimate around 3,000 "Poles." This includes people from Poland who were recruited in France and Belgium. It also includes volunteers of Belarusian, Ukrainian, and especially Jewish background. | |

| 2,500–4,700 | ||

| 2,341–2,800 | ||

| 1,500–2,095 | ||

| 1,600–1,722 | ||

| 1,546–2,000 | ||

| 1,101 | ||

| 1,006–1,500 | ||

| 740 | ||

| 628–691 | ||

| 550 | 220 died. | |

| 528–1,500 | ||

| 500 | About 799–1,000 from Scandinavia (500 were Swedes). | |

| 500 | ||

| 462 | ||

| 408–800 | ||

| 300–600 | ||

| 250 | They fought with the British Battalion and the Lincoln Battalion. | |

| 225 | 100 died. | |

| 225 | Including 78 Finnish Americans and 73 Finnish Canadians. About 70 died. | |

| 200 | ||

| 290–400 | ||

| 134 | Most Portuguese volunteers joined other Republican forces directly. | |

| 103 | ||

| 100 | Organized by the Chinese Communist Party. | |

| 90 | ||

| 60 | ||

| 60 | 16 of them died. | |

| 50 | ||

| 43 | They were part of the "Garibaldi Battalion" with Italians. | |

| 24 | ||

| "Perhaps 20" | They were mixed into British units. | |

| Others | 1,122 |

After the War: What Happened to the Brigadiers?

After the Spanish Civil War ended with the Nationalists winning, the brigadiers were often seen as being on the "wrong side." This was especially true because most of their home countries had right-wing governments.

However, many of these countries soon found themselves fighting against the same powers that had supported the Nationalists in Spain. Because of this, the brigadiers gained some respect. They were seen as the first to fight against fascism, showing that they had seen the danger early. It became clear that the war in Spain was like a preview of World War II.

Some glory came to the volunteers, and many survivors also fought in World War II. But this recognition often faded because of fears that it would promote communism.

Some left-wing groups, like anarchists, have criticized the Brigades. They believe the Brigades, or at least their leaders, played a role in stopping the Spanish Revolution. Films like Land and Freedom and books like George Orwell's Homage to Catalonia share this view.

East Germany's View

After World War II, Germany was divided. East Germany, a new communist country, wanted to create its own identity, different from Nazi Germany. The Spanish Civil War and the International Brigades became a big part of East Germany's history. This was because many German communists had served in the brigades. It showed that many Germans had fought against fascism.

Canada's Experience

When survivors of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion returned to Canada, they were often investigated by the police. They were sometimes denied jobs. Some were even stopped from serving in the military during World War II because they were seen as "politically unreliable."

In 1995, a monument was built in Ontario to honor veterans of the war. In 2001, the few remaining Canadian veterans dedicated another monument in Ottawa.

Poland's Story

In Poland, citizens who volunteered for the International Brigades automatically lost their citizenship. After the Republican defeat, many fighters recruited in France and Belgium returned there. Others served in anti-German groups in Poland or joined the Polish army formed in the USSR.

In Communist Poland, the International Brigades fighters were called "Dąbrowszczacy" and were given veteran rights. They sometimes held high positions in government. But they also faced suspicion, arrest, and even prison on false charges. They were released in the mid-1950s.

The fighters were highly praised between the mid-1950s and mid-1960s. Many books were written, and schools and streets were named after them. However, later, their importance was lessened, and many left Poland. Even today, the role of Polish International Brigades fighters is a debated topic. Some see them as heroes, while others see them as traitors.

Switzerland's Neutrality

In Switzerland, many people supported the Spanish Republic. But the government banned all fundraising and recruiting for the war. This was part of Switzerland's long-standing policy of neutrality. About 800 Swiss volunteers joined the International Brigades, including a few women. Most were communists, but others were socialists, anarchists, and anti-fascists.

Around 170 Swiss volunteers died in the war. The survivors were put on trial when they returned to Switzerland. They were charged with breaking the law against serving in a foreign army. About 420 people were sentenced to prison, from two weeks to four years. They also often lost their political rights for up to five years. Swiss historians say volunteers were punished more severely in Switzerland than in other democratic countries.

There have been repeated attempts to pardon the Swiss brigadiers because they fought for a good cause. In 2009, the Swiss Parliament finally passed a law to pardon them. By then, only a few were still alive. A monument honoring Swiss International Brigades fighters was unveiled in Geneva in 2000.

United Kingdom's Welcome

When the brigades were disbanded, 305 British volunteers returned home. They arrived at Victoria Station in London on December 7, 1938. They were warmly welcomed as heroes by many supporters.

The last surviving British member of the International Brigades, Geoffrey Servante, died in April 2019 at age 99.

International Brigade Memorial Trust

The International Brigade Memorial Trust is a charity that keeps alive the memory of volunteers from Britain and Ireland. They have a map of memorials to volunteers and organize yearly events to remember the war.

United States' "Premature Anti-Fascists"

In the United States, returning volunteers were called "premature anti-fascists" by the FBI. They were sometimes denied promotions if they served in the U.S. military during World War II. They were also investigated by Congress during the "Red Scare" period (1947–1957). However, threats to take away their citizenship were not carried out.

Recognition and Legacy

Josep Almudéver, believed to be the last surviving veteran of the International Brigades, passed away in May 2021 at 101 years old. He had both Spanish and French citizenship and joined the brigades to avoid age limits in the Spanish Republican army.

Spain's Citizenship Offer

On January 26, 1996, the Spanish government gave Spanish citizenship to the roughly 600 remaining brigadiers. This fulfilled a promise made by Prime Minister Juan Negrín in 1938.

France's Recognition

In 1996, Jacques Chirac, then the French President, gave former French members of the International Brigades the legal status of "former service personnel." This happened after two French communist Members of Parliament, whose parents were volunteers, requested it. Before 1996, this request had been turned down many times.

Symbols and Design

The International Brigades used symbols that showed their socialist ideas. Their flags featured the colors of the Spanish Republic: red, yellow, and purple. They often included socialist symbols like red flags, the hammer and sickle, and the raised fist. The brigades' own symbol was a three-pointed red star, which was often seen on their flags and emblems.

See also

In Spanish: Brigadas Internacionales para niños

In Spanish: Brigadas Internacionales para niños

- Foreign involvement in the Spanish Civil War

- International Legion of Territorial Defense of Ukraine

- International Freedom Battalion