Iroquois facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Iroquois Confederacy

Haudenosaunee

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

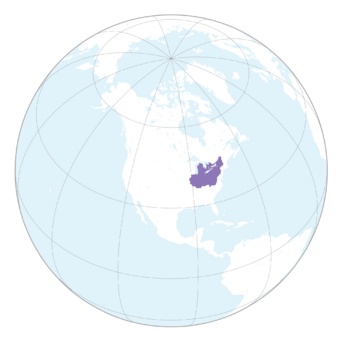

Map showing historical (in purple) and currently recognized (in pink) Iroquois territory claims.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Recognized confederate state, later became an unrecognized state | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Iroquoian languages | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Confederation | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Grand Council of the Six Nations | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

Between 1450 and 1660 (estimate) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

1867- (slow removals of sovereignty) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||

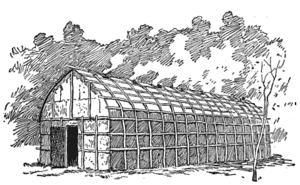

The Iroquois, also known as the Haudenosaunee or "People of the Longhouse", are a group of Native American tribes. They live in North America. These tribes, who spoke Iroquoian languages, came together a long time ago. This happened in what is now central and upstate New York.

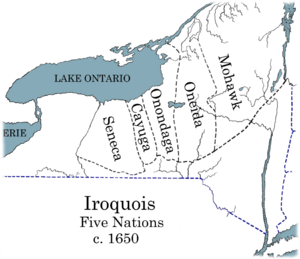

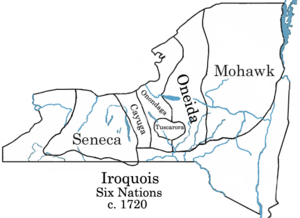

In the 16th century or earlier, they formed a group called the Iroquois League. It was also known as the "League of Peace and Power". At first, the Iroquois League had five nations: the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca. They were called the Five Nations. In 1722, the Tuscarora nation joined them. After that, they became known as the Six Nations. Even today, fifty sachems (chiefs) from different Iroquois clans meet. Their Grand Council meets near Syracuse, New York.

When Europeans first arrived, the Iroquois lived in the northeastern United States. This was mainly in upstate New York, west of the Hudson River. Their land stretched through the Finger Lakes region. Today, most Iroquois people live in New York and Canada.

The Iroquois League is also called the Iroquois Confederacy. Some experts think the League and the Confederacy are slightly different. The "Iroquois League" refers to the traditions and culture of the Grand Council. The "Iroquois Confederacy" was a political and diplomatic group. It formed after Europeans started settling in America. The League still exists today. The Confederacy broke apart after the British and their Iroquois allies lost the American Revolutionary War.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The Iroquois call themselves the "Haudenosaunee". This means "People of the Longhouse". A more exact meaning is "They Are Building a Long House". They believe the Great Peacemaker gave them this name when the League was formed. It means the nations of the League should live together like families in one big longhouse.

Symbolically, each nation had a role in this "tribal longhouse":

- The Mohawk guarded the eastern door. They lived in the east, closest to the Hudson River.

- The Seneca guarded the western door. They controlled the land in western New York.

- The Onondaga lived in the center of Haudenosaunee land. They were the keepers of the League's central fire.

French colonists called the Haudenosaunee "Iroquois". This name might have come from a few places:

- It could be a French version of irinakhoiw. This was a Huron (Wyandot) name for the Haudenosaunee. It meant "black snakes" or "real adders". The Haudenosaunee and Huron were often enemies. The Huron were allies with the French.

- Some experts think "Iroquois" came from a Basque word, hilokoa. This meant "the killer people". Basque fishermen traded with the Algonquins. The Algonquins were enemies of the Haudenosaunee. The word might have changed as Algonquins and French pronounced it differently.

A Look at History

How the League Began

The members of the Iroquois League speak Iroquoian languages. These languages are quite different from other Iroquoian languages. This suggests that the Iroquoian tribes shared a history and culture. But they separated for a long time, and their languages changed. Old tools and sites show that Iroquois ancestors lived in the Finger Lakes region from at least 1000 AD.

After forming the League, the Iroquois moved into the Ohio River Valley in what is now Kentucky. They did this to find more hunting grounds. The Iroquois League was formed before they met Europeans. Most archaeologists think the League was created between 1450 and 1600. Some believe it was even earlier.

Stories say that two men, Deganawida (the Great Peacemaker) and Hiawatha, formed the League. They brought a message called the Great Law of Peace to the warring Iroquoian nations. The nations that joined were the Seneca, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, and Mohawk. Once they stopped most of their fighting, the Iroquois quickly became very powerful. This was in the 17th and 18th centuries in northeastern North America.

Legend says that an evil Onondaga chief named Tadodaho was the last to accept the Great Law of Peace. He was convinced by the Great Peacemaker and Hiawatha. Tadodaho became the spiritual leader of the Haudenosaunee. This is said to have happened near Onondaga Lake in Syracuse, New York. The title Tadodaho is still used for the League's spiritual leader. This chief is the fiftieth chief and sits with the Onondaga in council. He is the only one of the fifty chosen by all the Haudenosaunee people. The current Tadodaho is Sid Hill of the Onondaga Nation.

Beaver Wars

In the 1600s, the Iroquois fought with other tribes. They were fighting for hunting lands. This time is known as the Beaver Wars.

French and Indian Wars

During the French and Indian War, the Iroquois sided with the British. They fought against the French and their Algonquian allies. The French and Algonquians had been enemies of the Iroquois before. The Iroquois hoped that helping the British would bring them rewards after the war. However, few Iroquois actually joined the British campaigns. In the Battle of Lake George, some Mohawk and French even ambushed a British group led by Mohawk.

After the war, the British government made the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This rule said that white settlers could not live past the Appalachian Mountains. But settlers mostly ignored this rule. The Iroquois agreed to move this boundary again in 1768. This was at the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. There, they sold the British their remaining land claims between the Ohio and Tennessee Rivers.

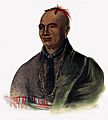

American Revolution

During the American Revolution, many Tuscarora and Oneida sided with the American colonists. But the Mohawk, Seneca, Onondaga, and Cayuga stayed loyal to Great Britain. This was the first big split among the Six Nations. Joseph Louis Cook helped the United States. He became a Lieutenant Colonel, the highest rank for any Native American during the war.

However, the Mohawk war chief Joseph Brant and other chiefs led successful attacks. They targeted frontier settlements with British allies. The future United States wanted revenge. In 1779, George Washington ordered the Sullivan Campaign. This campaign, led by Col. Daniel Brodhead and General John Sullivan, aimed to "destroy" the British-Indian alliance.

After the American Revolution

After the war, the League's central fireplace was restarted at Buffalo Creek. Colonel Joseph Brant and some Iroquois left New York. They settled in Canada. The British Crown rewarded them for their loyalty. They received a large land grant, now called Brantford, Ontario, on the Grand River.

Life and Culture

Food and Farming

Traditionally, the Iroquois were farmers, fishers, gatherers, and hunters. Most of their food came from farming. Their main crops were corn, beans, and squash. They called these the "three sisters." They believed these crops were special gifts from the Creator. These crops were grown in a smart way. Food was stored for two to three years. When the soil became less fertile, the Iroquois would move to a new area.

Gathering wild roots, greens, berries, and nuts was usually done by women and children in the summer. In spring, they collected maple syrup from trees. They also gathered herbs for medicine.

The Iroquois mostly hunted deer. They also hunted wild turkey and migratory birds. Muskrats and beavers were hunted in winter. Fishing was also a big food source. The Iroquois lived near large rivers like the St. Lawrence River. They fished for salmon, trout, bass, perch, and whitefish. In spring, they used nets. In winter, they made fishing holes in the ice.

Women in Society

When Europeans studied Iroquois customs, they found that women had a lot of power. This power was about equal to that of men. Women could own property, including homes, horses, and farmed land. When they married, they kept their property. It was not given to their husbands. A woman could also keep the money she earned.

A husband lived in his wife's family's longhouse. If a husband was not good, his wife could ask him to leave. He would take his belongings with him. Women were responsible for the children. Children were taught by members of the mother's family. Clans were matrilineal. This means family ties were traced through the mother's side. If a couple separated, the woman kept the children.

The chief of a clan could be removed at any time. This was done by a council of the mothers of that clan. The chief's sister was in charge of choosing the next chief.

Spiritual Beliefs

Important festivals happened at the same time as major farming events. These included a harvest festival of thanksgiving. The Great Peacemaker (Deganawida) was their prophet. After Europeans arrived, many Iroquois became Christians. One famous Christian was Kateri Tekakwitha, a young woman with Mohawk and Algonkin parents. Traditional Iroquois religious beliefs became popular again in the late 1700s. This was due to the teachings of the Iroquois prophet Handsome Lake.

The Six Nations

The Iroquois League started with five nations. The Tuscarora joined later, making it six. Here are the nations:

| English name | Iroquoian Name | Meaning | Old Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seneca | Onondowahgah | "People of the Great Hill" | Seneca Lake and Genesee River |

| Cayuga | Guyohkohnyoh | "People of the Great Swamp" | Cayuga Lake |

| Onondaga | Onöñda'gega' | "People of the Hills" | Onondaga Lake |

| Oneida | Onayotekaono | "People of Standing Stone" | Oneida Lake |

| Mohawk | Kanien'kehá:ka | "People of the Great Flint" | Mohawk River |

| Tuscarora1 | Ska-Ruh-Reh | "Hemp Gatherers" | From North Carolina² |

1 Not one of the original Five Nations; joined 1720.

2 Settled between Oneidas and Onondagas.

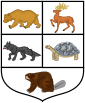

Clans

Within each of the six nations, people belong to different clans. These clans are matrilineal, meaning family lines are traced through the mother. The number of clans changes by nation, from three to eight. There are nine different clan names in total.

| Seneca | Cayuga | Onondaga | Tuscarora | Oneida | Mohawk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wolf (Hoñnat‘haiioñ'n‘) | Wolf | Wolf | Wolf (Θkwarì•nę) | Wolf (Thayú:ni) | Wolf (Okwáho) |

| Bear (Hodidjioiñi’'g’) | Bear | Bear | Bear (Uhčíhręˀ) | Bear (Ohkwá:li) | Bear (Ohkwá:ri) |

| Turtle (Hadiniǎ‘'děñ‘) | Turtle | Turtle | Turtle (Ráˀkwihs) | Turtle (A'no:wál) | Turtle (A'nó:wara) |

| Sandpiper (Hodi'ne`si'iu') | Sandpiper | Sandpiper | Sandpiper (Tawístawis) | – | – |

| Deer (Hadinioñ'gwaiiu') | – | Deer | Deer | – | – |

| Beaver (Hodigěn’'gegā’) | – | Beaver | Beaver (Rakinęhá•ha•ˀ) | – | – |

| Heron | Heron | – | – | – | – |

| Hawk | – | Hawk | – | – | – |

| – | – | Eel | Eel (Akunęhukwatíha•ˀ) | – | – |

Population Today

It's hard to know the exact number of Iroquois people today. In 1995, about 45,000 Iroquois lived in Canada. In the 2000 US census, 80,822 people said they were Iroquois. About 45,217 of them said they were only Iroquois. In 1995, about 30,000 people were officially registered with the Six Nations in the United States.

Grand Council and Government

The Grand Council of the Iroquois League is an assembly of 56 Hoyenah (chiefs) or Sachems. This number has never changed. Today, the seats on the Council are divided among the Six Nations like this:

- 14 Onondaga

- 10 Cayuga

- 9 Oneida

- 9 Mohawk

- 8 Seneca

- 6 Tuscarora

In the 1800s, an expert named Lewis Henry Morgan thought the Grand Council was a central government. This idea became very popular. But some experts now say that the Grand Council was more for ceremonies. They believe it was not a government in the way Morgan thought. Instead, Iroquois political decisions were made locally. They were based on what the local communities agreed upon. The Iroquois did not have a central government that made rules for everyone.

In 1855, Minnie Myrtle noted that no Iroquois treaty became official unless 75% of the male voters and 75% of the mothers of the nation approved it. To change Council laws, two-thirds of the mothers had to agree. This need for so much agreement made the Confederacy a government where everyone had to agree.

Women held real power. They could even say no to treaties or declarations of war. The members of the Grand Council of Sachems were chosen by the mothers of each clan. If a leader did not follow the wishes of the women or the Great Law of Peace, the mother of his clan could remove him. This was called "knocking off the horns." The deer antlers, a sign of leadership, were taken from his headgear. This meant he went back to being a regular person.

Councils of the mothers of each tribe were held separately from the men's councils. Women used men to carry messages about their decisions. Or a woman could speak at the men's council to share the women's views. Women often suggested new laws.

Festivals and Celebrations

The Iroquois traditionally celebrate several major festivals each year. These events usually combine spiritual ceremonies, a feast, and a chance to celebrate together. They also include sports and dancing. These celebrations have always been tied to the seasons and the cycle of nature. They are not on fixed calendar dates.

For example, the Mid-winter festival, called Gi'-ye-wä-no-us-quä-go-wä ("The supreme belief"), starts the new year. This festival usually lasts one week. It happens around late January to early February, depending on the new moon.

Iroquois ceremonies are mainly about farming, healing, and giving thanks. Key festivals match the farming calendar. These include Maple, Planting, Strawberry, Green Maize, Harvest, and Mid-Winter (or New Year's). The ceremonies were given by the Creator to help balance good and evil. In the 1600s, Europeans said the Iroquois had 17 festivals. Today, only 8 are celebrated.

The most important ceremonies were the New Year Festival and the Green Corn Festival. The Green Corn Festival celebrates when the corn is ready. During festivals, men and women from special societies like the False Face Society dance. They wear masks to entertain the spirits that control nature. Masked dancers were especially important at the New Year Festival. It was believed they could chase away bad spirits that caused sickness.

Games and Sports

The Iroquois' favorite sport is lacrosse. In Seneca, it's called O-tä-dä-jish′-quä-äge. Long ago, two teams of six or eight players played. Players were from different clans. The goals were two sets of poles about 450 yards (411 meters) apart. The poles were about 10 feet (3 meters) high and 15 feet (4.5 meters) apart. Players scored by carrying or throwing a deer-skin ball between the goal posts. They used netted sticks. Touching the ball with hands was not allowed. The game was played to a score of five or seven. The modern version of lacrosse is still very popular among the Haudenosaunee today.

The First Nations Lacrosse Association is recognized by World Lacrosse. It is seen as a sovereign state for international lacrosse games. It is the only sport where the Iroquois have national teams. It is also the only Native American organization allowed to compete internationally by a world sports group.

A popular winter game was the snow-snake game. The "snake" was a hickory pole. It was about 5–7 feet (1.5–2.1 meters) long and 0.25 inches (0.6 centimeters) thick. It was slightly curved at the front and weighted with lead. Two teams of up to six players played, often boys. Sometimes men from two clans played. The snake, or Gawa′sa, was held with the index finger at the back. It was balanced on the thumb and other fingers. It was not thrown but slid across the snow. The team whose snake went the farthest scored one point. If other snakes from the same team went farther than any opposing snake, they also scored a point. The other team scored nothing. This continued until one team reached the agreed-upon score, usually seven or ten.

The Peach-stone game (Guskä′eh) was a gambling game. Clans would bet against each other. It was traditionally played on the last day of the Green Corn, Harvest, and Mid-winter festivals. The game used a wooden bowl about one foot (30 centimeters) wide. It also used six peach pits. These pits were ground into an oval shape and burned black on one side. A "bank" of beans, usually 100, was used to keep score. The winner was the team that won all the beans.

Two players sat on a raised platform. To play, the peach pits were put into the bowl and shaken. Winning combinations were five of either color or six of either color showing. Players started with five beans each from the bank. The starting player shook the bowl. If he shook a five, the other player paid him one bean. If he shook a six, he got five beans. If he shook either, he got to shake again. If he shook anything else, the turn went to his opponent. All his winnings went to a "manager" for his side. If a player lost all his beans, another player from his side took his place. That player took five beans from the bank. Once all beans were taken from the bank, the game continued. But now, beans were drawn from the team's winnings. These winnings were kept hidden. So only the managers knew how the game was going. The game ended when one team won all the beans. This game could take a long time, sometimes more than a day.

Famous Iroquois People

- Henry Armstrong, a famous boxer.

- Joseph Louis Cook, a Mohawk leader.

- Chief John Big Tree, Seneca chief and actor.

- Governor Blacksnake, Seneca war chief.

- Joseph Brant, a well-known Mohawk leader.

- Canassatego, an Onondaga leader and diplomat. He suggested the British colonies form a confederacy like the Iroquois.

- Polly Cooper, an Oneida woman who helped the Continental Army during the American Revolution.

- Cornplanter, a Seneca chief.

- The Great Peacemaker, the traditional founder of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

- Gary Farmer, a Cayuga actor.

- Graham Greene, an Oneida and award-winning Canadian actor.

- Handsome Lake, a Seneca religious leader.

- Pauline Johnson, a Canadian writer and performer of Mohawk and European background.

- Stan Jonathan, a Mohawk professional hockey player.

- Tom Longboat, an Onondaga distance runner.

- Oren Lyons, an Onondaga traditional Faithkeeper.

- Shelley Niro, a Mohawk filmmaker and artist.

- Ely S. Parker, a Seneca Union Army officer and Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

- Red Jacket, a Seneca speaker and chief.

- Robbie Robertson, a Mohawk songwriter and musician from the band The Band.

- Jay Silverheels, a Canadian Mohawk actor who played Tonto in The Lone Ranger.

- Joanne Shenandoah, an Oneida singer and educator.

- Kateri Tekakwitha, the first Catholic Native American saint.

- Lyle Thompson, a professional lacrosse player.

- Miles Thompson, a professional lacrosse player.

Images for kids

-

Lithograph of the Mohawk war and political leader Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant

-

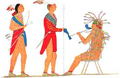

Member of the False Face Society

See also

In Spanish: Iroqués para niños

In Spanish: Iroqués para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |