Kanō Jigorō facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kanō Jigorō |

|

|---|---|

Kanō Jigorō

|

|

| Born | 28 October 1860 (in lunar calendar, Man'en 1st year) Mikage, Ubara-gun, Settsu Province, Edo Japan (present-day Hyogo Prefecture, Japan) |

| Died | 4 May 1938 (aged 77) Pacific Ocean (aboard Hikawa Maru) |

| Native name | 嘉納 治五郎 |

| Style | Judo, Jūjutsu |

| Teacher(s) | Fukuda Hachinotsuke; Iso Masatomo; Iikubo Tsunetoshi |

| Rank | Kōdōkan jūdō: Shihan (founder) Kitō-ryū: Menkyo kaiden (total transmission license) Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū: Instructor (formal rank unclear) |

| Occupation |

|

| University | University of Tokyo |

| Notable students | Mitsuyo Maeda Tomita Tsunejirō Fukuda Keiko Mifune Kyūzō Kotani Sumiyuki Mochizuki Minoru Saigō Shirō Yokoyama Sakujirō Yamashita Yoshitsugu Vasili Oshchepkov Gunji Koizumi Kenji Kanō |

Kanō Jigorō (嘉納 治五郎, 10 December 1860 - 4 May 1938) was a Japanese martial artist, teacher, and politician. He is famous for creating judo, a martial art that became popular worldwide. Judo was one of the first Japanese martial arts to be recognized internationally. It was also the first to become an official Olympic sport.

Kanō introduced new ideas to martial arts training. He started using black and white belts to show different skill levels. He also brought in the dan ranking system. This system shows how experienced a martial artist is. Kanō had famous sayings like "maximum efficiency minimal effort" (精力善用 (seiryoku zen'yō)) and "mutual welfare and benefit" (自他共栄 (jita kyōei)).

In his work life, Kanō was a dedicated educator. He held important jobs, like being the director of primary education for Japan's Ministry of Education (文部省, Monbushō) from 1898 to 1901. He was also the president of Tokyo Higher Normal School from 1900 to 1920. Kanō helped start Nada High School in Kobe, Japan. He played a big part in making judo and kendo a part of Japanese public school programs in the 1910s.

Kanō was also a leader in international sports. He was the first Asian member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), serving from 1909 to 1938. He represented Japan at most Olympic Games between 1912 and 1936. He was also a main speaker for Japan's effort to host the 1940 Olympic Games.

He received many official awards. These included the First Order of Merit and the Grand Order of the Rising Sun. Kanō was the first person to be added to the International Judo Federation (IJF) Hall of Fame on May 14, 1999.

Contents

Kanō's Early Life

His Childhood

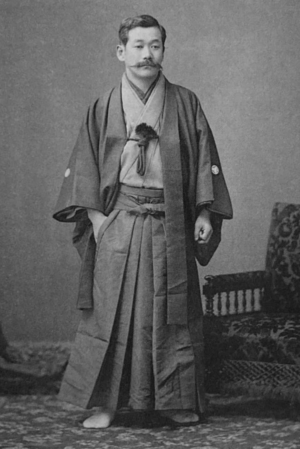

Kanō Jigorō was born in Mikage, Japan. His family made sake, a Japanese drink. However, Kanō's father, Kanō Jirōsaku, was an adopted son. He did not join the family business. Instead, he worked as a priest and a clerk for a shipping company.

Kanō's father believed strongly in education. He made sure Jigorō, his third son, got an excellent education. Jigorō's early teachers included smart scholars like Yamamoto Chikuun. Kanō's mother died when he was nine years old. After that, his father moved the family to Tokyo.

Young Kanō went to private schools. He also had a private English language tutor. In 1874, he went to a private school run by Europeans. This helped him improve his English and German. He became very good at English and even wrote his diary in that language.

When he was a teenager, Kanō was about 1.57 meters (5 feet 2 inches) tall. He weighed only about 41 kilograms (90 pounds). Other students often bullied him because he was small and very smart. They sometimes dragged him out of school to beat him. Kanō wished he was stronger so he could defend himself.

One day, a family friend named Nakai Baisei told Kanō about jūjutsu. Nakai said it was a great way to train physically. He showed Kanō some moves where a smaller person could beat a bigger, stronger opponent. Kanō saw that jūjutsu could help him defend himself. He decided he wanted to learn it. Nakai warned him that jūjutsu was old-fashioned and dangerous.

Kanō's father also did not want him to learn jūjutsu. He ignored the bullying his son faced. But when he saw how interested Kanō was, he allowed him to train. He made Kanō promise to try his best to master the art.

Learning Jūjutsu

Kanō started at the University of Tokyo in 1877. He earned a degree in Political Science and Philosophy in 1882. While at the university, he began searching for jūjutsu teachers. He first looked for seifukushi, who were bonesetters. He thought doctors who knew martial arts would be better teachers.

His search led him to Yagi Teinosuke. Yagi had been a student of Emon Isomata in the Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū school of jūjutsu. Yagi then sent Kanō to Fukuda Hachinosuke. Fukuda was a bonesetter who taught Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū in a small room next to his practice. Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū was a mix of two older schools: the Yōshin-ryū and Shin no Shindō-ryū.

Fukuda's teaching style involved students falling many times for the teacher. This helped them understand the moves. Fukuda focused on using techniques in real situations. He gave beginners a quick explanation of a move. Then, he had them practice freely (randori) to learn by doing. He taught traditional forms (kata) only after students became good at the basics. This was hard because there were no special mats, just straw mats (tatami) on wooden floors.

Kanō struggled to beat Fukushima Kanekichi, an older student. So, Kanō started trying new techniques on him. He first tried moves from sumo that he learned from Uchiyama Kisoemon. When that did not work, he studied more. He tried a move called "fireman's carry" from a book on Western catch wrestling. This move worked! The kataguruma, or "shoulder wheel," is still part of judo today.

On August 5, 1879, Kanō took part in a jūjutsu show for former U.S. president Ulysses S. Grant. This event happened at the home of a famous businessman, Shibusawa Eiichi. Other jūjutsu teachers, Fukuda Hachinosuke and Iso Masatomo, also took part. Fukuda died soon after this show at age 52.

Fukuda's students were a small group. Kanō was very skilled in randori and the best at kata. So, Fukuda's widow chose Kanō to inherit his school's teachings. She asked him to keep the dojo open. Kanō took on this teaching role for a while. But he soon decided he needed more training before leading a school.

Kanō then began studying with Iso Masatomo, who was Fukuda's friend. Iso was 62 years old and about 1.52 meters (5 feet) tall. But he was very strong from jūjutsu training. He was known for his excellent kata and for hitting vital points (atemi). Iso's method started with kata and then moved to free fighting (randori). Because Kanō practiced a lot and had a strong base from Fukuda's teaching, he became an assistant instructor at Iso's school. Iso Masatomo died in 1881.

While with Iso, Kanō saw a demonstration by the Yōshin-ryū jūjutsu teacher Totsuka Hikosuke. Kanō later practiced randori with students from Totsuka's school. Kanō kept learning from students and teachers of other schools. He found out that Motoyama Masahisa, a fellow University of Tokyo graduate, was the son of a master of the Kitō-ryū school. The elder Motoyama was old and only taught kata. Kanō had been looking for a new teacher after his last one died. Kanō's persistence led Motoyama to introduce him to Iikubo Tsunetoshi, a better Kitō-ryū master.

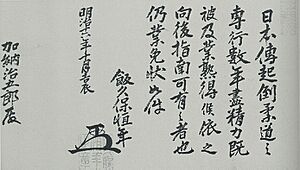

Kanō started training in Kitō-ryū with Iikubo Tsunetoshi. Iikubo was great at kata and throwing techniques. He also loved randori. Kanō worked hard to learn Kitō-ryū. He believed Iikubo's throwing techniques were better than those from his previous schools. Iikubo gave Kanō a formal jūjutsu rank and teaching license. This was a menkyo certificate in Kitō-ryū, dated October 1883.

Creating Kodokan Judo

How Judo Began

In the early 1880s, there was not a clear difference between the jūjutsu Kanō taught and what his teachers had taught. Kanō's Kitō-ryū teacher, Iikubo Tsunetoshi, came to Kanō's classes at the early Kodokan. He came two or three times a week to help Kanō teach. Over time, the student and master started to switch roles. Kanō began to defeat Iikubo during randori:

Usually it had been him that threw me. Now, instead of being thrown, I was throwing him with increasing regularity. I could do this despite the fact that he was of the Kito-ryu school and was especially adept at throwing techniques. This apparently surprised him, and he was quite upset over it for quite a while. What I had done was quite unusual. But it was the result of my study of how to break the posture of the opponent. It was true that I had been studying the problem for quite some time, together with that of reading the opponent's motion. But it was here that I first tried to apply thoroughly the principle of breaking the opponent's posture before moving in for the throw...

I told Mr. Iikubo about this, explaining that the throw should be applied after one has broken the opponent's posture. Then he said to me: "This is right. I am afraid I have nothing more to teach you."

Soon afterward, I was initiated in the mystery of Kito-ryu jujitsu and received all his books and manuscripts of the school.—Kanō Jigorō, in reporting his discovery

After these events, Iikubo gave Kanō his menkyo certificate. Iikubo also gave him a densho, which is a document a master gives to a student who becomes a master. Kanō kept teaching Kitō-ryū jūjutsu for a few more years. Records show he later received a menkyo kaiden. This is a scroll of Kitō-ryū Takenaka-ha, signed by Kanō Jigorō himself.

To name his new system, Kanō used a term from an older style. This term was "jūdō". The name combines jū (error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help), meaning "pliancy" or "gentle") and dō (dō, meaning "The Way" or "method").

Technically, Kanō combined the throwing moves of Kitō-ryū. He also used the choking and pinning moves of Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū. For example, judo's Koshiki-no-kata keeps the traditional forms of Kitō-ryū. Itsutsu-no-kata comes from Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū. There are only small changes from the original schools Kanō learned from. Many moves from Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū are also in judo's Kime-no-kata. However, Kime-no-kata was created by Kanō for his judo students.

Kanō's early work was shaped by different methods. He wrote in 1898, "By taking all the good points I had learned from various schools and adding my own ideas, I created a new system." This system was for physical training, moral growth, and winning contests. After judo was introduced into Japanese public schools (1906-1917), the forms (kata) and tournament techniques became more standard.

Judo Grows Stronger

Kanō also guided the growth of his judo organization, the Kodokan Judo Institute. This was a huge effort. The Kodokan started with fewer than twelve students in 1882. By 1911, it had over a thousand dan-ranked members.

In May or June 1882, Kanō started Kodokan judo in a small room. It had twelve mats and was in a Buddhist temple in Tokyo. Iikubo came three days a week to help teach. Kanō had only a few students then. But they got better by regularly competing with local police jūjutsu teams.

The Kodokan moved to a bigger space in April 1890. It had 60 mats. In December 1893, the Kodokan began moving to an even larger place. This move was finished by February 1894.

The Kodokan's first kangeiko, or winter training, happened in 1894–1895. Midsummer training, or shochugeiko, began in 1896. E.J. Harrison wrote about these trainings:

all [Japanese judo] dojo including the Kodokan hold special summer and winter exercises. For the former, the hottest month of the year, August, and the hottest time of the day, from 1 pm, are chosen; and for the latter commencing in January, the pupils start wrestling at four o'clock in the morning and keep it up until seven or eight. The summer practice is termed shochugeiko and the winter practice kangeiko. There is likewise the 'number exercise' on the last day of the winter practice when as a special test of endurance, the pupils practice from 4 am till 2 pm and not infrequently go through as many as a hundred bouts within that interval.

In the late 1890s, the Kodokan moved two more times. First, to a 207-mat space in November 1897. Then, to a 314-mat space in January 1898. In 1909, Kanō officially made the Kodokan a corporation. He gave it 10,000 yen (about $4,700 then). The Japan Times said on March 30, 1913, that this was "so that this wonderful institution might be able to reconstruct... the moral and physical nature of the Japanese youth."

The Kodokan moved one last time during Kanō's life. On March 21, 1934, the Kodokan opened a new 510-mat building. Ambassadors from Belgium, Italy, and Afghanistan attended the opening. In 1958, the Kodokan moved to its current eight-story building. This new building has over 1200 mats. The old building was sold to the Japan Karate Association.

Judo's Big Ideas

On April 18, 1888, Kanō and Reverend Thomas Lindsay gave a talk. It was called "Jiujitsu: The Old Samurai Art of Fighting without Weapons." This talk happened at the British Embassy in Tokyo. The main idea was that judo wins by giving in to strength.

Kanō was an idealist. He had big goals for judo. He saw it as something that included self-defense, physical fitness, and good behavior.

Since the very beginning, I had been categorizing Judo into three parts, rentai-ho, shobu-ho, and shushin-ho. Rentai-ho refers to Judo as a physical exercise, while shobu-ho is Judo as a martial art. Shushin-ho is the cultivation of wisdom and virtue as well as the study and application of the principles of Judo in our daily lives. I therefore anticipated that practitioners would develop their bodies in an ideal manner, to be outstanding in matches, and also to improve their wisdom and virtue and make the spirit of Judo live in their daily lives. If we consider Judo first as a physical exercise, we should remember that our bodies should not be stiff, but free, quick and strong. We should be able to move properly in response to our opponent's unexpected attacks. We should also not forget to make full use of every opportunity during our practice to improve our wisdom and virtue. These are the ideal principles of my Judo.

"Because judo developed based on the martial arts of the past, if the martial arts practitioners of the past had things that are of value, those who practice judo should pass all those things on. Among these, the samurai spirit should be celebrated even in today's society"

In 1915, Kanō defined judo:

Judo is the way of the highest or most efficient use of both physical and mental energy. Through training in the attack and defence techniques of judo, the practitioner nurtures their physical and mental strength, and gradually embodies the essence of the Way of Judo. Thus, the ultimate objective of Judo discipline is to be utilized as a means to self-perfection, and thenceforth to make a positive contribution to society.

In 1918, Kanō added:

Don't think about what to do after you become strong – I have repeatedly stressed that the ultimate goal of Judo is to perfect the self, and to make a contribution to society. In the old days, Jūjutsu practitioners focused their efforts on becoming strong, and did not give too much consideration to how they could put that strength to use. Similarly, Judo practitioners of today do not make sufficient efforts to understand the ultimate objective of Judo. Too much emphasis is placed on the process rather than the objective, and many only desire to become strong and be able to defeat their opponents. Of course, I am not negating the importance of wanting to become strong or skilled. However, it must be remembered that this is just part of the process for a greater objective... The worth of all people is dependent on how they spend their life making contributions.

In March 1922, Kanō created the Kodokan Bunkakai, or Kodokan Cultural Association. This group had its first meeting on April 5, 1922. It gave its first public talk three days later. The group's mottos were "Good Use of Spiritual and Physical Strength" and "Prospering in Common for Oneself and Others." These are often translated as "Maximum Efficiency with Minimum Effort" and "Mutual Welfare and Benefit."

Kanō explained judo's purpose in a lecture:

The purpose of my talk is to treat of judo as a culture: physical, mental, and moral, – but as it is based on the art of attack and defense, I shall first explain what this judo of the contest is…

A main feature of the art is the application of the principles of non-resistance and taking advantage of the opponent's loss of equilibrium; hence the name jūjutsu (literally soft or gentle art), or judo (doctrine of softness or gentleness)...

...of the principle of the Maximum Efficiency in Use of Mind and Body. On this principle the whole fabric of the art and science of judo is constructed.

Judo is taught under two methods, one called randori, and the other kata. Randori, or Free Exercise, is practised under conditions of actual contest. It includes throwing, choking, holding down, and bending or twisting the opponent's arms or legs. The combatants may use whatever tricks they like, provided they do not hurt each other, and obey the general rules of judo etiquette. Kata, which literally means Form, is a formal system of prearranged exercises, including, besides the aforementioned actions, hitting and kicking and the use of weapons, according to rules under which each combatant knows beforehand exactly what his opponent is going to do.

The use of weapons and hitting and kicking is taught in kata and not in randori, because if these practices were resorted to in randori injury might well arise...

As to the moral phase of judo, – not to speak of the discipline of the exercise room involving the observance of the regular rules of etiquette, courage, and perseverance, kindness to and respect for others, impartiality and fair play so much emphasized in Western athletic training, – judo has special importance in Japan...

Kanō's Career

A Dedicated Educator

Kanō promoted judo whenever he could. But he earned his living as a teacher.

Kanō started at the University of Tokyo in June 1877. He studied political science and economics. One of his favorite teachers was the American scholar Ernest Fenollosa. Kanō graduated in July 1882. The next month, he became a professor at the Gakushuin, or Peers School, in Tokyo. In 1883, Kanō became a professor of economics at Komaba Agricultural College. In April 1885, he returned to Gakushuin as the principal.

In January 1891, Kanō got a job at the Ministry of Education. In August 1891, he left this job to become a dean at the Fifth Higher Normal School. This is now Kumamoto University. Around this time, Kanō got married. His wife, Sumako Takezoe, was the daughter of a former Japanese ambassador to Korea. They eventually had six daughters and three sons.

In the summer of 1892, Kanō went to Shanghai. He helped create a program for Chinese students to study in Japan. Kanō visited Shanghai again in 1905, 1915, and 1921.

In January 1898, Kanō became the director of primary education at the Ministry of Education. In August 1899, he received money to study in Europe. He left Japan on September 13, 1899, and arrived in Marseilles on October 15. He spent about a year in Europe, visiting Paris, Berlin, Brussels, Amsterdam, and London. He returned to Japan in 1901.

Soon after returning, he became president of Tokyo Higher Normal School again. He stayed in this job until he retired on January 16, 1920. He also helped start Nada Middle High School in 1928 in Kobe. This school later became one of the best private high schools in Japan.

Kanō's family thought he would work for the government after college. He was even offered a job at the Ministry of Finance. But his love for teaching led him to Gakushuin instead. Students at Gakushuin were from Japan's elite families. They had higher social positions than their teachers. Students could ride in rickshaws right to their classes. Teachers were not allowed to. Teachers often felt forced to visit students' homes when called. They were treated like servants.

Kanō thought this was wrong. He refused to act like a servant when teaching. To Kanō, a teacher must be respected. He also used the newest European and American teaching methods. The ideas of American educator John Dewey especially influenced him. Kanō's way of teaching worked well with the students. But the school leaders were slower to accept his methods. It was not until a new principal arrived that Kanō's ideas were accepted.

Kanō's teaching ideas mixed traditional Japanese beliefs with modern European and American philosophies. These included ideas about practical learning and progress.

The goals of Kanō's teaching were: to develop minds, bodies, and spirits equally; to increase love for one's country and loyalty to the Emperor; to teach good morals; and to make people physically strong, especially for military service.

Exercises like Calisthenics could be boring. At high school and college, games like baseball and rugby were often watched more than played. Also, at high levels, sports like baseball and judo did not focus much on moral or intellectual growth. Instead, coaches often cared most about winning.

For Kanō, the answer was judo. Not just throwing people around, and definitely not winning at any cost. Instead, it was judo based on "Maximum Efficiency with Minimum Effort" and "Mutual Welfare and Benefit." As Kanō told a reporter in 1938: "When yielding is the highest efficient use of energy, then yielding is judo."

Judo and the Olympics

Kanō became involved with the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1909. This happened after Kristian Hellström asked Japan and China if they would send teams to the 1912 Olympics. Japan's government did not want to say no. So, the Ministry of Education asked Kanō to look into it. Kanō was a physical educator with recent experience in Europe, so he was a good choice.

Kanō agreed to represent Japan on the IOC. After talking to the French ambassador and reading pamphlets, he said he got "a fairly good idea of what the Olympic Games were."

To do his job as a member, Kanō helped create the Japan Amateur Athletic Association in 1912. This group oversaw amateur sports in Japan. Kanō was Japan's official representative at the Stockholm Olympics in 1912. He also helped organize the Far Eastern Championship Games in Osaka in May 1917.

In 1920, Kanō represented Japan at the Antwerp Olympics. In the early 1920s, he served on the Japanese Council of Physical Education. He did not play a big part in organizing the Far Eastern Championship Games in Osaka in May 1923. He also did not go to the 1924 Olympics in Paris. But he did represent Japan at the Olympics in Amsterdam (1928), Los Angeles (1932), and Berlin (1936). From 1931 to 1938, he was also a main international speaker for Japan's bid to host the 1940 Olympics.

Kanō's main goal was to bring people together with friendly feelings. However, his goals did not specifically include getting judo into the Olympics. As he wrote in a letter in 1936:

I have been asked by people of various sections as to the wisdom and the possibility of Judo being introduced at the Olympic Games. My view on the matter, at present, is rather passive. If it be the desire of other member countries, I have no objection. But I do not feel inclined to take any initiative. For one thing, Judo in reality is not a mere sport or game. I regard it as a principle of life, art and science. In fact, it is a means for personal cultural attainment. Only one of the forms of Judo training, the so-called randori can be classed as a form of sport... [In addition, the] Olympic Games are so strongly flavoured with nationalism that it is possible to be influenced by it and to develop Contest Judo as a retrograde form as Jujitsu was before the Kodokan was founded. Judo should be as free as art and science from external influences – political, national, racial, financial or any other organised interest. And all things connected with it should be directed to its ultimate object, the benefit of humanity.

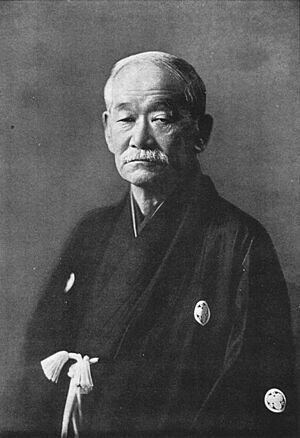

His Legacy

In 1934, Kanō stopped giving public demonstrations. This was because his health was failing. He likely had kidney stones. The British judoka Sarah Mayer wrote that people thought he would not live much longer. Still, Kanō kept attending important Kodokan events. He also continued his work with the Olympics.

In May 1938, Kanō died at sea. He was on a ship, the Hikawa Maru, as a member of the IOC. His official cause of death was pneumonia. Some sources say it was food poisoning.

Judo did not end with Kanō. In the 1950s, judo clubs appeared all over the world. In 1964, judo became an Olympic sport when Tokyo hosted the 1964 Summer Olympics. It was brought back for good at the 1972 Summer Olympics. Kanō's fame was secured. His true legacy, however, was his idealism. As Kanō said in a speech in 1934, "Nothing under the sun is greater than education. By educating one person and sending him into the society of his generation, we make a contribution extending a hundred generations to come."

Kanō has been compared to the 9th Marquess of Queensberry. Both created new rules that changed their sports.

Dr Kano's Kodokan rules for his version of jujitsu brought a new, safer kind of fighting to Japan in the same way that the Queensberry Rules, introduced some two decades earlier in 1867, did for boxing in England. Both the Marquess of Queensberry and Dr Kano transformed their sports, making them cleaner and safer. One man took the grappling out of boxing; the other took the boxing out of grappling. One worked with a padded fist; the other with a padded floor. In the latter years of the nineteenth century, the martial histories of eastern and western civilisation had reached a point at which two men at opposite ends of the globe produced, within a few years of each other, the rules which were to herald unarmed combat’s own age of enlightenment.

Awards and Recognition

- Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon, 1938 (Japan).

- On October 28, 2021, Google honored Jigorō's 161st birthday. They featured him with a doodle on their homepage.

See also

In Spanish: Jigorō Kanō para niños

In Spanish: Jigorō Kanō para niños

- Hard and soft (martial arts)

- Idaten (TV series)

- Judo technique

- Kosen judo

- Kuzushi

- Matsugoro Okuda

- The Principle of Ju

- Sanshiro Sugata

- Statue of Kanō Jigorō, Shinjuku