Korean mythology facts for kids

| Korean mythology | |

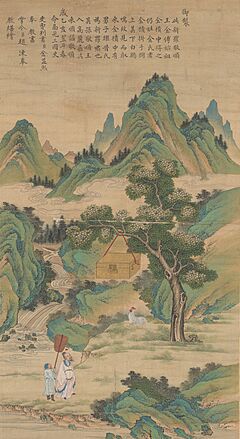

Early 19th-century painting showing thirty-two shamanic gods. The three young gods in white (bottom center) are the Jeseok triplets, gods of good luck and new life.

|

|

Quick facts for kids Korean name |

|

|---|---|

| Hangul | |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Hangung sinhwa |

| McCune–Reischauer | Han'gung shinhwa |

Korean mythology (Korean: 한국 신화; Hanja: 韓國神話; MR: Han'guk sinhwa) is a collection of myths told by Koreans throughout history. There are two main types of myths. Some are written in old history books, mostly about how ancient kingdoms and their first kings started. The other type is much larger and more varied. These are oral myths, meaning they were spoken or sung. Shamans (priestesses) sang these stories during special ceremonies to call upon the gods. Many of these stories are still considered sacred today.

The written myths, often found in old books like Samguk Sagi and Samguk Yusa, tell how states were founded. For example, the story of Dangun tells how the first Korean nation began. These founding myths are sometimes divided into "northern" and "southern" types. Northern myths, like that of Goguryeo and its founder Jumong, feature a founder born from a sky god and an earthly woman. Southern myths, like that of Silla and its founder Hyeokgeose, describe a founder who comes from the heavens as an object and then marries an earthly woman. Other written myths explain the origins of important family groups.

The stories of Korean shamanism, Korea's traditional religion, include many different gods and people. Shamans tell these stories during rituals to please the gods and entertain the people watching. Since they are oral stories, shamans often change them a little each time they perform them, but the main parts stay the same. New stories have even appeared since the 1960s. Shamanic myths often challenge traditional ideas, like how men were usually in charge.

Shamanic myths are grouped into five regional traditions. Each region has its own unique stories, plus its own versions of myths found across Korea. The myths from Jeju Island in the south are especially different. Two important stories found almost everywhere are the Jeseok bon-puri, about a girl who has triplets who become gods, and Princess Bari, about a princess abandoned by her father who later brings her dead parents back to life.

Contents

Korean Myths: Written and Spoken Stories

Korean mythology has two main types of stories. The first type is the written mythology (문헌신화/文獻神話, munheon sinhwa). These are recorded in old Korean history books, like the 13th-century book Samguk Yusa. The myths in these books are often mixed with historical facts, making it hard to tell what's real and what's myth. The main written myths are the state-foundation myths (건국신화/建國神話, geon'guk sinhwa). These tell how a kingdom or ruling family began. This group also includes other magical stories from history books and origin stories of non-royal families.

The second type is the modern oral mythology (구비신화/口碑神話, gubi sinhwa). This group is much richer and more diverse than the written stories. Oral myths are mostly shamanic narratives (서사무가/徐事巫歌, seosa muga). Korean shamans sing these stories during gut, which are religious ceremonies where shamans call on the gods. These stories are very different from the written myths in what they do and what they contain.

State-foundation myths only exist in writing and have been around for centuries. But shamanic narratives are "living mythology." They are sacred religious truths for those who take part in the gut. They only started to be published in 1930. Unlike the written myths, shamanic songs tell about the world's first history, how people become gods, and how gods punish disrespectful humans.

Scholars began studying Korean mythology by looking at the written myths. But research into the oral stories was small until the 1960s. Since the 1990s, new studies have compared Korean myths with those from nearby countries. They also look at myths about village gods and use feminist ideas to understand the stories.

Oral mythology is always religious. It's different from general Korean folklore, which can be just regular stories. For example, the Woncheon'gang bon-puri is a Jeju shamanic story about a girl who becomes a goddess. It's a myth because it's sacred and about a goddess. A similar Korean folktale, the Fortune Quest, is not a myth because it's not sacred. Some Korean myths used to be folktales, and many folktales used to be myths.

Written Myths: Stories of Kingdoms and Families

Founding Myths of Kingdoms

Founding myths tell the story of the first ruler of a new Korean kingdom. They include the ruler's special birth, how they created their kingdom, and their amazing death or departure. People often think these stories are based on real events from when the kingdom was founded.

The oldest stories about the founding of ancient Korean kingdoms like Gojoseon, Goguryeo, and Silla are written in old Chinese. These stories are found in Korean books from the 12th century or later, such as Samguk Sagi and Samguk Yusa. These books used even older sources that are now lost. Some ancient Chinese texts also tell these myths. For Goguryeo, there are also five Chinese stone monuments that tell the kingdom's founding myth from the Goguryeo people's point of view. The oldest is the Gwanggaeto Stele, put up in 414 CE.

The founding myth of the Goryeo dynasty (10th to 14th centuries) is in Goryeosa, a history book from the 15th century. Yongbieocheonga, a poem from the same time, is sometimes seen as the founding myth of the later Joseon dynasty. Since Joseon was the last Korean dynasty, there are no newer founding myths.

Long ago, state founding myths were also told orally, maybe by shamans. A poet named Yi Gyu-bo (1168–1241) said that both written and spoken versions of the Goguryeo founding myth were known in his time. The modern Jeseok bon-puri shamanic story is similar in structure to the old Goguryeo myth and might be a direct descendant of that ancient tale.

Ancient founding myths (before Goryeo) are split into two main types: northern and southern. Both types share the idea of a king connected to the heavens. In the northern kingdoms like Gojoseon, Buyeo, and Goguryeo, the first king is born from a sky god and an earthly woman. In the southern kingdoms like Silla and Geumgwan Gaya, the king comes from a physical object that falls from heaven. Then, he marries an earthly woman himself. In northern myths, the god-like king takes over from his heavenly father or creates a new kingdom. In the south, local leaders choose the heavenly being to be king.

Northern Kingdoms: Gojoseon, Buyeo, Goguryeo, and Baekje

Gojoseon

The founding myth of Gojoseon, Korea's earliest kingdom, is first written down in two books from the late 1200s: Samguk Yusa and Jewang Ungi.

Here's the story from Samguk Yusa: Hwanung, a younger son of the sky god Hwanin, wanted to rule the human world. Hwanin saw that his son could "greatly benefit the human world." So, he gave Hwanung three special treasures to take to Earth. Hwanung came down under a sacred tree on Mount Taebaek (meaning "great white mountain"). There, he and 3,000 followers started the "Sacred City." With the gods of wind, rain, and clouds, Hwanung managed human affairs.

A bear and a tiger asked Hwanung to turn them into humans. The god gave them 20 pieces of garlic and some sacred mugwort. He told them they would become human if they ate these and stayed out of sunlight for 100 days. The bear became a woman after 21 days. The tiger failed and stayed an animal. The bear-woman prayed for a child at the sacred tree. Hwanung granted her wish by becoming human and marrying her. She gave birth to a boy named Dangun Wanggeom, who founded the kingdom of Gojoseon in Pyongyang. Dangun ruled for 1,500 years. He later became a mountain god.

The Dangun myth is a "northern type" because the founder is born from a heavenly father (Hwanung) and an earthly mother (the bear). This story is often seen as a myth about three groups of people. One group worshipped a sky god, another had a bear as their symbol, and a third had a tiger. The tiger group was somehow removed, and the bear group joined the sky god group to create Gojoseon.

Dangun was likely worshipped only in the Pyongyang area until the 13th century. At that time, scholars tried to make the Korean state stronger during Mongol attacks. They did this by saying Dangun was the ancestor of all Korean people. By the 20th century, he was accepted as the mythical founder of the Korean nation. He is important in both North and South Korea's ideas about their country.

Buyeo, Goguryeo, and Baekje

The founding myth of the northern kingdom of Goguryeo is told in detail in Samguk Sagi (1145) and Dongmyeongwang-pyeon (1193) by Yi Gyu-bo. Yi's version is longer and more detailed.

Here's a summary of the Dongmyeongwang-pyeon myth: Haeburu, the ruler of Buyeo, had no children. One day, he found a boy who looked like a golden frog (金蛙 geumwa). He adopted him as his son. Later, Haeburu moved his court to the Sea of Japan and founded the kingdom of Eastern Buyeo.

Haemosu, the son of the sky god, came down to Haeburu's old capital in 59 BCE. He arrived on a chariot pulled by five dragons and started a new kingdom there. One day, Haemosu met the three beautiful daughters of the god of the Yalu River. He took Yuhwa, the oldest. The angry river god challenged Haemosu to a shapeshifting fight, but Haemosu won. The river god let Haemosu marry Yuhwa, but Haemosu went back to heaven without his wife after the wedding.

The river god sent Yuhwa away. A fisherman found her and took her to Geumwa, the frog-king, who now ruled Eastern Buyeo. He kept her in a part of his palace. One day, sunlight from the heavens fell on Yuhwa. She gave birth to an egg from her left armpit, and a boy hatched from it. The boy was very strong. He could shoot down flies with a bow, so he was named Jumong, meaning "good archer." The king made Jumong a stable-keeper. This made Jumong angry, so he decided to start his own kingdom. With three friends, Jumong fled south, leaving his mother and wife behind. When they reached a river that was too deep to cross, Jumong said he was from the gods. The fish and turtles in the river let them cross on their backs. Jumong founded the kingdom of Goguryeo in 37 BCE. A local leader named Songyang opposed him. After some fights, Songyang gave up when Jumong caused a big flood in his country.

Yuri, Jumong's son from his wife left in Eastern Buyeo, asked his mother who his father was. She told him the truth. Yuri solved a riddle his father had left and found his father's token, half of a sword. He went to Goguryeo and met Jumong. Yuri and Jumong matched their sword halves, and the sword became whole, oozing blood. When Jumong asked his son to show his power, the boy rode on sunlight. Jumong then made Yuri his heir. In 19 BCE, the king went up to heaven and did not return. Yuri held a funeral for his father, using the king's whip instead of his missing body, and became Goguryeo's second king.

The founding of the southwestern kingdom of Baekje is also linked to the Jumong myth. According to the Samguk Sagi, when Yuri became heir, Jumong's two sons by a local wife were not chosen to be king. These two brothers, Biryu and Onjo, moved south to start their own kingdoms. Biryu chose a bad place, while Onjo founded Baekje in a good area, which is now southern Seoul. Biryu died of shame when he learned his brother's kingdom was doing well. His people then joined Baekje.

The Jumong myth is a "northern type" because Haemosu is the heavenly father and Yuhwa is the earthly woman. Old Chinese records say that Jumong and Yuhwa were worshipped as gods by the Goguryeo people. Like the Dangun myth, this story is also seen as a myth based on real events. For example, some scholars believe Haemosu represents an ancient group of people who used iron and worshipped the sun.

Southern Kingdoms: Silla and Gaya

Silla

The ancient Silla kingdom was first ruled by three families: the Bak, the Seok, and the Kim. Later, the Seok family lost power. After that, all Silla kings were children of a Kim father and a Bak mother. All three families have their own founding myths.

The Bak family's founding myth is told in detail in Samguk Yusa. Six leaders from the Gyeongju area met to create a united kingdom. They saw a strange light shining on a well. When they went there, they saw a white horse kneeling. The horse went up to heaven, leaving a large egg behind. The leaders broke open the egg and found a beautiful boy inside. They named him Hyeokgeose.

Later, a chicken-dragon gave birth to a beautiful girl with a chicken beak from its left rib. When they washed the girl in a stream, the beak fell off. When the boy and girl were 13 years old, the leaders crowned them as the first king and queen of Silla. They gave the king the family name Bak. Hyeokgeose ruled for 61 years and then went up to heaven. The queen died soon after.

Samguk Yusa also tells the Seok and Kim family founding myths. In the Seok myth, a ship surrounded by magpies landed on the Silla coast. Inside the ship was a giant chest. When they opened it, they found slaves, treasures, and a young boy. The boy, Seok Talhae, said he was a prince from a country called Yongseong ("dragon castle"). When he was born as an egg, his father put him in the chest and sent him away to found his own kingdom. Seok settled in Silla. He tricked the rich man Hogong to steal his house and married the oldest daughter of the Silla king. He became king after his father-in-law and founded the Seok family. After he died, he became the guardian god of a local mountain. A village myth very similar to the Seok Talhae story is still told by shamans on Jeju Island.

Hogong also appears in the Kim family's founding myth. One night, Hogong saw a bright light in the woods. When he got closer, he found a golden chest hanging from a tree and a white rooster crowing below. He opened the chest and found a boy, whom he named Alji. Alji was brought to the court and made the Silla king's heir, but he later gave up his position. Alji became the mythical founder of the Kim family, which later produced all the Silla kings.

Gaya

Before Silla conquered them in the 6th century, the Gaya groups lived in the southern Nakdong River delta. The Samguk Yusa tells the founding myth of one of the most powerful Gaya kingdoms, Geumgwan Gaya. The nine leaders of the country heard a strange voice say that heaven had ordered a kingdom to be founded there. After singing and dancing as the voice commanded, a golden chest wrapped in red cloth came down from heaven. When the leaders opened it, they found six golden eggs. The eggs hatched into giant boys who grew up in just two weeks. On the 15th day, each of the six became kings of the six Gaya kingdoms. The first to hatch, Suro, became king of Geumgwan Gaya.

Later, Suro was challenged by Seok Talhae, the founder of the Seok family. According to the history of Gaya in Samguk Yusa, they had a shapeshifting duel. Seok admitted defeat and fled to Silla. A beautiful princess named Heo Hwang'ok then arrived on a ship with red sails. She brought great wealth from a faraway kingdom called Ayuta. Heo told Suro that Shangdi (a heavenly ruler) had told her father to marry her to Suro. They became king and queen and lived for over 150 years.

The founding myths of Silla and Gaya are "southern type." The founder comes directly from heaven in things like eggs and chests. These myths might also reflect real historical people and events. For example, Hyeokgeose might represent ancient horse-riders from the north who created Silla with the help of local leaders.

Other Written Myths

Another type of written myth tells the origin stories of specific family lines. These are found in family records. The idea of a founding ancestor being born from a stone or golden chest also appears in the records of many non-royal families. Other ancestor myths involve a human and a non-human having children. For example, the Chungju Eo family (eo means "fish") claims to be descended from a man born to a human mother and a carp father. The Changnyeong Jo family is thought to come from a Silla noblewoman and the son of a dragon.

Shamanic and Oral Mythology

Nature and Context

Shamanic narratives are oral stories sung during gut. These large-scale shamanic rituals are part of Korean shamanism, Korea's traditional religion with many gods.

Since the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), Koreans have had mixed feelings about their traditional religion. The Joseon rulers, who followed Neo-Confucianism, were against shamanism. They tried hard to remove it from public life. As Koreans accepted the Joseon state's ideas, shamanism became more linked to women, who were also less important in the new society. Shamanism was only allowed as a private religion for women, without public power.

Even today, shamanism is still important in Korea, but people still have mixed feelings about it. In 2016, Seoul alone had hundreds of ritual places where gut were held almost every day. Yet, many worshippers, who might also be Christians or Buddhists, avoid talking about their shamanic worship in public. They sometimes even call their own beliefs superstition.

Because of these mixed feelings, shamanism and its myths are often seen as challenging Korea's main values. However, some myths also include mainstream ideas like Confucian virtues. The story of Princess Bari is a good example. The myth is about the princess's journey to the world of the dead to save her parents. This shows filial piety, a Confucian virtue (respect for parents). But the person who saves her parents is a daughter, not a son. Her parents abandoned her at birth just for being a girl. Later, Bari leaves her husband for her parents, even though Confucian culture said women should be loyal to their husband's family after marriage. So, the myth uses Confucian values to challenge the idea that men are always in charge.

All shamanic narratives serve both religious and entertainment purposes. Shamanic narratives are almost never sung outside of religious ceremonies. The ritual setting is very important to fully understand the myths. For example, the story of Bari is performed at ceremonies where the soul of a dead person is sent to the afterlife. Bari is the goddess who guides the soul. Her story helps comfort grieving families, assuring them that their loved one's spirit is safe. At the same time, shamans also try to entertain the worshippers. They might add riddles, popular songs, or funny descriptions to the story. Musicians might also interrupt with jokes. These funny parts also helped to share the challenging messages of many shamanic myths, like criticism of gender roles and social classes.

As oral stories, shamanic narratives are shaped by both old traditions and the shaman's own new ideas. Many stories have long, set phrases and images that appear the same in different versions of the myth. Shamans memorize these when they learn the songs. For example, descriptions of Bari's mother's pregnancies are found in all versions of the Princess Bari myth. On the other hand, shamans often add new content and change phrases. The same shaman might even sing different versions of a myth depending on the specific gut. However, some consistency is expected. In one case, a Jeju shaman telling the Chogong bon-puri story was interrupted many times for getting details wrong. Shamanic mythology is quite traditional for oral literature.

Unlike written myths, shamanic myths are a living tradition that can create new stories. In the 1960s, a shaman in Gangwon Province changed the Simcheongga story, about a blind man, into a new Simcheong-gut story. This new myth is sung to prevent eye disease and has become very popular. Another new myth is the Jemyeon-gut story, which appeared in 1974. It has no clear source, and its details have grown since the 1970s. Several other shamanic stories seem to have come from or are related to popular stories from the late Joseon period. Similarities have also been found between Korean shamanic stories and other East Asian myths, especially those of Manchu shamanism.

Korean shamanism is changing. Traditional village ceremonies are becoming less common, while rituals for individuals are increasing. Gut are now often held in private places with only shamans and the worshippers, unlike the public ceremonies of the past. Most individual worshippers are not very interested in the myths themselves. They sometimes even leave when the story begins. They are more interested in parts of the ceremony that relate directly to them or their families. With other forms of entertainment available, the entertainment value of shamanic rituals has also gone down. In Seoul, for example, the Princess Bari performance is getting shorter. Many new shamans now learn stories from books or recordings instead of from experienced shamans. This might mean that the regional differences in the myths are decreasing.

Unlike the gods in Greek or Norse myths, the gods in Korean shamanic mythology mostly exist on their own. Each shamanic story explains what its gods are like and what they do. But gods from different stories rarely interact with each other. So, it's not possible to create a family tree of these gods.

Regional Traditions of Shamanic Myths

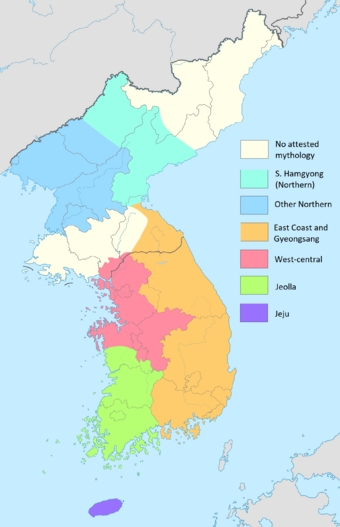

Shamanic mythology is divided into five regional traditions (무가권/巫歌圈 muga-gwon). These show the main differences in the two widespread myths, the Jeseok bon-puri and the Princess Bari. Each of the five regions also has myths not found elsewhere. The myths of southern Jeju Island are especially different.

A unique thing about Korean mythology is that it's least rich near the capital of Seoul, which was the center of the country. It's largest and most diverse in South Hamgyong Province and Jeju Island, the northernmost and southernmost edges. These two outer mythologies are the oldest. Several similar myths are found in both Hamgyong and Jeju, even though they are far apart. This suggests they both came from a common ancient Korean source.

Northern Tradition

The northern tradition is not well understood because it's now part of North Korea, where research is difficult. The religion of South Hamgyong Province might be a distinct shamanic tradition. South Hamgyong myths include many unique stories. One important one is the Song of Dorang-seonbi and Cheongjeong-gaksi, about a woman trying to meet her dead husband. Other notable South Hamgyong myths include the Seng-gut (which combines creation and Jeseok bon-puri), the Donjeon-puri (about a couple who become money gods), and the Jim'gajang (about three boys who get revenge by being reborn as their murderer's sons). In contrast, Hwanghae province in North Korea has almost no shamanic myths. Instead of myths, they have a strong tradition of ceremonial dance and theater.

West-Central Tradition

The west-central tradition covers Seoul and its surrounding areas. It strongly emphasizes the sacred nature of the stories. The stories are mainly for the gods, not for the people watching. Shamans often use traditional, set phrases. This tradition is considered the most "solemn" of Korean shamanic narratives. This might be because Seoul shamans often performed for queens and other court women in royal palaces, who would expect serious rituals. This region also has the fewest myths. The only specific west-central story is Seongju-puri, which explains the origins of the household's guardian god. In Seoul itself, Princess Bari is the only shamanic story performed.

East Coast and Gyeongsang Tradition

Unlike the west-central tradition, shamans of the East Coast and Gyeongsang tradition work hard to make their stories entertaining for the human worshippers. Stories are told with great detail and many different ways of speaking. The musicians do more than just play background music; they join in the performance. The shaman also talks with the audience. Non-shamanic music, like folk songs or Buddhist hymns, is added at the right moments. Special regional stories include a very detailed account of the journeys of the Visitors, who are the gods of smallpox. This region currently has the most active mythological tradition.

Jeolla Tradition

The Jeolla tradition has less focus on the common Korean myths. Instead, two other myths are more important: the Jangja-puri, about a rich man who avoids the gods of death, and the Chilseong-puri, about seven brothers who become gods of the Big Dipper. As of 2002, the Jeolla mythology was becoming less common.

Jeju Tradition

The Jeju tradition also emphasizes how sacred the myths are. The shaman always sings the stories facing the altar, with their back to the musicians and worshippers. The clear goal of Jeju mythology, as many stories say, is to make the gods "giddy with delight" by telling them their life stories and deeds. The island has the richest collection of shamanic stories. It is the only tradition where Princess Bari is not known. The Jeju mythological tradition is also at risk, as the longest Jeju gut rituals, which take 14 days, are rarely held completely nowadays. Several myths are no longer performed by shamans.

Creation Narratives

Several Korean shamanic stories talk about the creation and early history of the world. The most complete creation stories are found in the northern and Jeju traditions. One is also known from the west-central tradition. Some East Coast versions of the Jeseok bon-puri also include parts about creation.

The northern and Jeju creation stories share many ideas. In both, the universe is created when heaven and earth, which were once joined, separate. A giant is often involved in creation. In one northern story, the creator god Mireuk, who separates heaven and earth, is said to have eaten huge amounts of grain and worn robes with very long sleeves. In both northern and Jeju myths, a good god is challenged by someone who tries to take over the human world. The two gods have three contests to decide who will rule. In both, the last challenge is a flower-growing contest. The god who grows the better flower will take charge of humanity. The good god grows the better flower, but the other god steals it while the good god sleeps. Having won this last contest, the bad god takes control of the world. His unfair victory is the reason for the evil and suffering in the world today. Both northern and Jeju creation myths also tell how there were once two suns and two moons, making the world very hot during the day and very cold at night, until a god destroyed one of each.

However, the northern and Jeju creation myths are different in how they are structured. In the north, the two main characters are the creator Mireuk and the usurper Seokga. Both are Buddhist names, referring to Maitreya and Shakyamuni. But since the myths are not otherwise related to Buddhism, people believe these were originally local gods whose names were later changed. The two gods have two duels of magical power before the final flower contest. In most stories, the sun and moon double or disappear after Seokga's unfair victory. The bad god then has to go on a quest to fix the cosmic order by finding the sun and moon or destroying the extra ones. Only the northern tradition talks about how humans were created. One story says Mireuk grew insects into humans.

The Jeju creation myth does not show Buddhist influence. In Jeju, the sky god Cheonji-wang comes down to Earth after creation, often to punish a disrespectful man named Sumyeong-jangja. There, he falls in love with an earthly woman and gives her two gourd seeds as tokens before returning to the heavens. The woman gives birth to twin boys, Daebyeol-wang and Sobyeol-wang. When the brothers grow up, they plant the gourd seeds, which grow into giant vines that reach into heaven. The twins climb these vines to enter their father's realm. After confirming they are his sons, the twins hold a contest to decide who will rule the human world and who will rule the world of the dead. After two riddle contests, the younger twin wins the final flower contest by cheating and takes charge of the living. The world ruled by Sobyeol-wang, where humans live, is full of suffering and disorder. But Daebyeol-wang creates justice and order for his kingdom of the afterlife, where human souls go after death.

Jeseok bon-puri

The Jeseok bon-puri is the only myth found in all five regional traditions across Korea. The mainland versions of this story tell the origins of the Jeseok gods,[[efn|name=Jeseok|The name "Jeseok" is used everywhere except in the East Coast-Gyeongsang tradition, where names like "Sejon" are used. Both Jeseok and Sejon are Buddhist names. Jeseok is the Korean name for the Buddhist god Indra, and Sejon means "world-honored," an East Asian title for the Buddha. The worship of Sejon is also linked to new life and good fortune.]] who are gods of fertility and bring good fortune and success in farming. They are also often linked to Samsin Halmoni, the goddess of childbirth. As of 2000, there were 61 known versions of the Jeseok bon-puri, not counting the very different Jeju versions.

All versions share this basic story: Danggeum-aegi is the unmarried daughter of a nobleman. When her parents and brothers are away, a Buddhist priest comes to her house asking for donations. Danggeum-aegi gives him rice. The priest usually delays by spilling the rice, so she has to pick it up and offer it again.

In the Jeolla tradition, the priest briefly touches her wrist before leaving. In the west-central tradition, Danggeum-aegi eats three grains of rice that the priest spilled. In the northern and East Coast-Gyeongsang traditions, the girl offers the priest a room in her father's house. He refuses every room until she agrees to share her own room with him. She then becomes pregnant with his child. When her family returns, they try to save their family's honor but fail.

In the west-central and Jeolla traditions, they then kick her out of the house. Danggeum-aegi finds the priest and gives birth to sons in front of him, usually triplets. The priest leaves Buddhism and starts a family with her and the sons. In the Jeolla tradition, the myth ends here without anyone becoming gods. In the west-central tradition, the priest makes his sons with Danggeum-aegi into the Jeseok gods.

In the northern and East Coast-Gyeongsang traditions, the family traps Danggeum-aegi in a pit or stone chest. But she magically survives and always gives birth to triplet sons. Danggeum-aegi is then brought back to the family. In most versions, the triplets are super talented. Other children try to murder them out of jealousy but fail. One day, the triplets ask who their father is. Danggeum-aegi usually names different trees as their father, but each tree tells the triplets she is lying. Once she tells the truth, the brothers go to find their father. When they reach the priest's temple, he gives them a series of impossible tasks to prove they are his sons. This includes walking in water with paper shoes without getting them wet, crossing a river using only the bones of cows dead for three years, creating a rooster out of straw that crows, and eating a fish and then vomiting it out alive. The triplets succeed in all tasks. The priest knows they are his sons when his blood mixes with the triplets'. The priest then makes Danggeum-aegi the goddess of childbirth, and the triplets become the Jeseok gods or similar fertility gods.

In the northern and eastern traditions, the Jeseok bon-puri is often linked to the creation story. The usurper Seokga is the same god as the priest Danggeum-aegi falls in love with. The northern versions where the Jeseok bon-puri follows the creation story are likely the oldest.

Even though the priest seems Buddhist, he has many qualities of a sky god. In some versions, the priest lives in a heavenly palace, or rides into his home in the clouds on a paper horse, or takes Danggeum-aegi to heaven using a rainbow as a bridge. Many versions call the priest or his temple "Golden." This might come from an old Korean phrase meaning "the Great God." So, the myth is about an earthly woman falling in love with a heavenly man and having children who become worshipped. Scholars have noticed similarities between Danggeum-aegi and the priest's meeting and Yuhwa and Haemosu's meeting in the Goguryeo founding myth. They also see parallels between the triplets' quest to find their father and become gods, and Yuri's quest to find Jumong and become king.

Princess Bari

The Princess Bari story is found in all regions except Jeju. Scholars have written down about 100 versions of this myth. As of 1998, all known versions were sung only during gut rituals for the dead. Princess Bari is therefore a goddess closely connected to funeral ceremonies. Bari's exact role changes depending on the version. Sometimes she doesn't become a goddess at all. But usually, she is known as the patron goddess of shamans, the guide of dead souls, or the goddess of the Big Dipper.

Despite many versions, most agree on the basic story. The first main part in almost all versions is the marriage of the king and queen. The queen gives birth to six daughters in a row, who are treated very well. When she is pregnant a seventh time, the queen has a good dream. The royal couple thinks this means she will finally have a son and prepares celebrations. Sadly, the child is a girl. The disappointed king orders the daughter to be thrown away, naming her Bari, from the Korean word beori (beori) meaning "to throw away."[[efn|Or 바리데기 Bari-degi "thrown-away baby"]] In some versions, she has to be abandoned two or three times because animals protect her the first and second times. The girl is then rescued by someone like the Buddha, a mountain god, or a stork.

Once Bari has grown up, one or both of her parents become very sick. They learn that the disease can only be cured with special medicinal water from the Western Heaven. In most versions, the king and queen ask their six older daughters to get the water, but all of them refuse. Desperate, the king and queen order Princess Bari to be found again. In other versions, the royal couple is told in a dream or prophecy to find their daughter. In any case, Bari is brought to court. She agrees to go to the Western Heaven and leaves, usually dressed as a man.

The details of Bari's journey differ in each version. In one of the oldest recorded stories, told by a shaman near Seoul in the 1930s, she meets the Buddha after traveling a very long distance. Seeing through her disguise, the Buddha asks if she can truly go another long distance. When Bari says she will keep going even if she dies, he gives her a silk flower. This flower turns a vast ocean into land for her to cross. She then frees millions of dead souls trapped in a huge fortress of thorns and steel.

When Bari finally reaches the medicinal water, she finds it guarded by a magical being. This guardian also knows she is a woman. He makes her work for him and have his sons. Once this is done—she might give birth to as many as 12 sons—she is allowed to return with the medicinal water and the flowers of resurrection. When she returns, she finds that her parents (or parent) have already died and their funerals are happening. She stops the funeral, opens the coffins, and brings her parents back to life with the flowers and cures them with the water. In most versions, the princess then becomes a goddess.

Each of the four mainland regional traditions has unique parts of the Princess Bari story. The west-central tradition has strong Buddhist influence. The rescuer is always the Buddha, who brings her to be raised by an old couple who want good karma. The East Coast and Gyeongsang tradition adds the most details to Bari's journey. It shows the guardian of the medicinal water as an exiled god who needs sons to return to heaven. The Jeolla tradition is the least detailed and doesn't mention Bari dressing as a man. There is great variety even within regions. For example, the 1930s version mentions a wood of resurrection, but most other versions use a flower.

The northern tradition has only two versions, both from South Hamgyong. They are very different. The princess does not reach the divine realm on her own but through divine help. There, Bari steals the flowers of resurrection and flees. She suddenly dies at the end of the story without becoming a goddess, and the mother she resurrected dies soon after. Her role in funerals as the link between the living and the afterlife is taken by the local goddess Cheongjeong-gaksi.

The Princess Bari has been informally linked to the royal court. There is some evidence that King Jeongjo supported its performance for the soul of his father, Prince Sado, who died in 1762. Modern Seoul shamans say an older version of the story had many terms specific to the Korean court. Similarities have also been found between this story and the Manchu folktale Tale of the Nishan Shaman.

Localized Mainland Narratives

Most mainland shamanic stories are local. They are told only in one or two specific regions. South Hamgyong Province was especially rich in these local myths. For example, nine different stories were told during the Mangmuk-gut funeral ritual alone. One of the most popular myths in South Hamgyong was the Song of Dorang-seonbi and Cheongjeong-gaksi. This myth is about a woman named Cheongjeong-gaksi, who is heartbroken by the death of her husband Dorang-seonbi. The priest from the Golden Temple gives her a series of tasks to meet her husband again. These tasks include tearing out all her hair, twisting it into a rope, making holes in her palms, and hanging from the rope through her palms without screaming. She also had to put her fingers in oil for three years, then pray while setting them on fire. Finally, she had to pave rough mountain roads using only her bare hands.

Despite succeeding in all this, she could only be reunited with Dorang-seonbi in the afterlife. Later, they both became gods. Dorang-seonbi and Cheongjeong-gaksi were the most important gods called upon in the Mangmuk-gut funeral. They were even worshipped in Buddhist temples as second only to the Buddha himself.

The local story of the Visitors (손님네 sonnim-ne), a group of wandering male and female smallpox gods, is most common in the East Coast-Gyeongsang tradition. This story covers very different themes from the sad romance above. It was traditionally performed to calm these dangerous gods during smallpox outbreaks. The goal was for them to cause only mild cases of the disease and to prevent future outbreaks.

Jeju Narratives

The Jeju tradition has the richest mythology. Its shamanic stories, called bon-puri (본풀이), are divided into three or four types. About a dozen general bon-puri are known by all shamans. These stories are about gods with universal roles who are worshipped throughout the island. The village-shrine bon-puri are about the guardian gods of a specific village. Only shamans from that village and its neighbors know these stories. The ancestral bon-puri are about the patron gods of specific families or jobs. Despite the name, the god is often not seen as an actual ancestor. Only shamans from the family or job know these, so they are not well understood. Some studies also include a small fourth type called "special bon-puri," which are no longer performed in rituals by shamans.

Many general bon-puri are clearly related to mainland stories but have unique Jeju features. A good example is the Chogong bon-puri, the Jeju version of the Jeseok bon-puri, but with a very different ritual purpose. The early part of the Chogong bon-puri is similar to Jeseok bon-puri versions from Jeolla, the closest part of the mainland. After finding out she is going to have a baby, the teenage Noga-danpung-agassi (the Jeju version of Danggeum-aegi) is kicked out of her home and goes to find the priest. But in Jeju, the priest sends her away to give birth to the triplets alone. Unlike in Jeolla, but like in the northern and eastern traditions, the triplets grow up without a father.

When the triplets beat 3,000 Confucian scholars in the civil service examinations, the jealous scholars murder Noga-danpung-agassi. The triplets visit their father for help. The priest makes them leave their old life and become shamans. The triplets hold the first shamanic rituals to successfully bring their mother back to life. Then, they become divine judges of the dead to bring justice to the scholars in the afterlife. When asked about the origin of a ritual, Jeju shamans say, "it was done that way in the Chogong bon-puri."

Village-shrine bon-puri are dedicated to the guardian gods of one or more villages. Most follow a set pattern. In their most complete form, a hunting god who eats meat comes from the hills of Jeju, and a farming goddess arrives from overseas, often China. The two marry and become village gods, but then separate. This usually happens because the goddess cannot stand the god's bad habits or the smell of his meat. The goddess then gives birth to a third god, who is sent away from the island. This god goes on adventures abroad before returning to settle as the god of a different village. Many villages only have parts of this story. For example, the bon-puri might end with the marriage, or only involve the god appearing or arriving. Many Jeju village gods are also thought to be related to each other. One of the most important village bon-puri is about the gods of Songdang shrine. These gods are the parents or grandparents of 424 guardian gods of various villages and places on the island.

Mainland Village-Shrine Myths

Like in Jeju, mainland Korean villages traditionally have specific guardian gods. The Joseon dynasty strongly promoted Confucian ways of worshipping these gods over traditional shamanic practices. By the late 19th century, most important rituals for village gods were held by men following Confucian rules, even using Chinese instead of Korean. So, the sacred stories linked to these gods are not (or no longer) shamanic narratives, except on Jeju Island.

However, many of these stories reflect shamanic beliefs, such as the importance of calming sad spirits. Like shamanic narratives, village-shrine myths are closely linked to rituals for the god. They often explain who the worshipped god is. Village mythology is also a living tradition. For example, in the village of Soya, North Gyeongsang Province, people now believe that the local guardian god accurately predicted which soldiers from the village would survive World War II.

In a study of 94 village-shrine myths from South Jeolla Province, Pyo In-ju divides the myths into two main groups. One group identifies the god as a natural object, and the other as a human spirit. The most common natural objects in the myths are trees, dragons, and rocks. For example, in the village of Jangdong in Gwangyang, a local tree is said to have wept one day during the Japanese invasion of 1592. While all the villagers gathered at the tree because of this strange sound, the Japanese attacked. Finding the village empty, they suspected a trap and left. A few days later, the Japanese returned and tried to cut down the tree. But the tree dropped giant branches on them and killed them all. The Japanese never dared to approach the village again. Since then, locals have worshipped the tree as a god.

Village gods identified as human spirits are often the founder of the village. Or they might be a sad spirit (원혼/願魂, wonhon) who stayed in the human world after death because of their grief or anger. For example, they might have been murdered or died as a child.

See also

- Chinese mythology

- Japanese mythology

- Mongol mythology

- Manchu shamanism

- Vietnamese mythology

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |