Ludwig Klages facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ludwig Klages

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 10 December 1872 |

| Died | 29 July 1956 (aged 83) |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater |

|

| Awards | Goethe Medal for Art and Science (1932) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

|

Main interests

|

Aesthetics, anthropology, classical studies, ..., handwriting, intellectual history, metaphysics, philosophy of history, philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, poetry, psychology |

|

Notable ideas

|

|

| Co-founder of | Munich Cosmic Circle |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Theoretical psychology, characterology, chemistry |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Attempt at a Synthesis of Menthone (1901) |

| Doctoral advisor | Alfred Einhorn |

| Other academic advisors | Theodore Lipps |

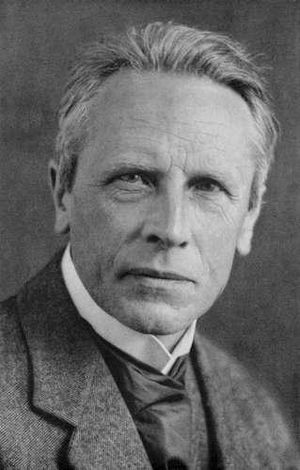

Ludwig Klages (born December 10, 1872 – died July 29, 1956) was an important German philosopher, psychologist, and writer. He was also a graphologist, which means he studied handwriting. Klages was nominated twice for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Many people in Germany consider him one of the most important thinkers of the 1900s.

He started his career studying chemistry because his family wanted him to. But he soon went back to his true interests: poetry, philosophy, and classical studies (the study of ancient Greece and Rome). He worked at the University of Munich. In 1905, he started a special psychology seminar there. This seminar had to close in 1914 when World War I began. In 1915, Klages moved to Switzerland, which was a neutral country during the war. He wrote many of his most important philosophical books there. Ludwig Klages passed away in 1956.

Klages was a key figure in characterology, a field of psychology that studies character. He was also part of a philosophy movement called Lebensphilosophie, which focuses on life itself. A main idea in his thinking was his view on language. He introduced the term "logocentrism". This term describes when people focus too much on words and language, forgetting the real things those words refer to. His ideas about this were very important for studying how language works in Western science and philosophy. His work also influenced critical theory, deep ecology (a philosophy about the environment), and existential phenomenology (a philosophy about human experience).

Some people compare Klages' role in modern psychology to that of his famous friends, Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. His ideas were even criticized by Nazi leaders during his lifetime. However, whether he supported the Nazis has been debated. Even though not many of his writings were translated into English, Klages had a huge impact on psychology, psychiatry, and literature in Germany.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Ludwig Klages was born in Hannover, Germany, on December 10, 1872. His father, Friedrich Ferdinand Louis Klages, was a businessman and a former military officer. His mother was Marie Helene Kolster. In 1878, his sister Helene was born, and they were very close throughout their lives.

When Klages was nine years old, in 1882, his mother died. It is believed she passed away from pneumonia. His aunt, Ida Kolster, came to live with the family to help raise the children. This was what his mother had wished for.

Klages went to school at the Lyceum am Georgsplatz in Hannover. His early schooling focused on classic subjects like ancient Greek and Roman studies. He quickly became very interested in writing poetry and prose. He also loved learning about ancient Greece and Germany. His father was very strict and tried to stop him from writing poetry. But Klages continued to write, despite his father's and teachers' wishes.

Klages became very good friends with a classmate named Theodor Lessing. They shared many interests. Klages tried to keep their friendship strong, even though his father did not approve of him being friends with Jewish people. Lessing later wrote that Klages' father did not like his son being friends with "Juden."

In 1891, Klages finished his high school education. He then went to Leipzig University to study physics and chemistry. His father wanted him to work in industrial chemistry. He studied at Leipzig for two semesters. Then he studied for one semester at the Technische Hochschule Hannover (now the University of Hannover).

Munich Years

In 1893, Klages moved to Munich. He continued his studies at Munich University. In the same year, he joined the Chemisches Institut. This was a chemistry lab at the university. While studying, he also became involved in the lively cultural scene in Schwabing. This was a bohemian area of Munich.

In 1894, Klages met Hans Busse, a poet and sculptor. Busse had just started an institute for scientific graphology (handwriting analysis). At that time, handwriting analysis was seen as a respected field. Busse sometimes gave expert opinions in court cases. Klages was very interested in this subject because of Busse. Other important people Klages met then included psychiatrist Georg Meyer, poet Stefan George, and classicist Alfred Schuler.

After finishing his studies, Klages continued to work as a research chemist. He also started writing his doctoral thesis under Alfred Einhorn. Klages' poems and prose began to appear in Blätter für die Kunst. This was a journal owned by Stefan George, who recognized Klages' talent.

In 1896, Klages, Meyer, and Busse started a new graphology organization. It was called the Deutsche Graphologische Gesellschaft (German Graphological Society). Klages' friendship with Theodor Lessing ended in 1899. Both later wrote about how important their friendship had been.

In 1900, Klages earned his doctorate in chemistry from the University of Munich. Because chemistry had moved from the medical faculty, he received a philosophy doctorate (PhD). In 1901, he published his thesis, which was titled Attempt at a Synthesis of Menthone.

Later Career in Switzerland

When World War I started in 1914, Klages moved to Switzerland. He earned a living by writing and giving lectures. He returned to Germany in the 1920s. In 1932, he received the Goethe Medal for Art and Science.

However, by 1936, the Nazi government began to criticize him. They said he did not support them enough. On his 70th birthday in 1942, many German newspapers spoke out against him. After World War II, the new German government honored him. This was especially true on his 80th birthday in 1952.

Key Ideas

Klages' ideas are often seen as a link between Friedrich Nietzsche and many modern continental philosophy thinkers. Klages himself once said his work was "the most plundered" of his time. Jürgen Habermas, another philosopher, thought Klages was far ahead of his time. Habermas described Klages' philosophy as "anti-spiritual." This means Klages was one of the first to criticize the idea of "spirit" as something against life.

Much of Klages' work uses very precise German philosophical language. He also sometimes used special, less common words.

He developed a full theory of graphology, the study of handwriting. He is known for ideas like "form level" and "bi-polar interpretation" in handwriting analysis. Along with Friedrich Nietzsche and Henri Bergson, he helped shape existential phenomenology. He also created the term "logocentrism" in the 1920s.

As a philosopher, Klages took Nietzsche's ideas about Lebensphilosophie (philosophy of life) to their furthest point. He made a difference between Seele (soul), which supports life, and Geist (spirit or intellect), which he saw as harmful to life. Geist represented modern, industrial, and intellectual ways of thinking. Seele represented a way to overcome this thinking and connect more with the earth.

After Klages died, Jürgen Habermas said that Klages' ideas in anthropology (the study of humans) and the philosophy of language should be studied more. He felt these ideas were hidden behind Klages' complex ideas about metaphysics and history. Habermas believed Klages' thinking in these areas was very advanced for his time.

Klages influenced many people. Some of his admirers included the Jewish thinker Walter Benjamin, philosopher Ernst Cassirer, and novelist Hermann Hesse.

Personal Views

Political and Other Views

Klages was generally seen as not interested in politics. His ideas sometimes matched those of deep ecology, which focuses on protecting the environment. He also supported feminism by rejecting what he saw as Christian patriarchy. He was a strong pacifist, meaning he was against war. He opposed Germany's involvement in both World War I and World War II.

Despite his opposition to fascist militarism, some people mistakenly thought he supported Nazism. However, Klages was criticized by Nazi authorities during his career. There have been debates about whether he held antisemitic views. Some scholars have pointed to certain remarks he made, especially in a 1940 publication. However, other scholars, like Paul C. Bishop, argue that Klages was "not a fundamentally anti-semitic thinker, not a right-wing philosopher, and not a Nazi."

Klages was critical of Christianity and what he saw as its connections to Judaism. Some scholars have suggested he might have leaned towards polytheism or pantheism, similar to ancient Greek thinkers. However, his exact religious views are not fully clear.

Works

Klages wrote 14 books and 60 articles between 1910 and 1948. He also helped edit the journal Berichte (1897–1898) and its follow-up, Graphologische Monatshefte, until 1908.

Selected Books in German

- Vom Wesen des Bewusstseins (1921)

- Vom kosmogonischen Eros (1922)

- Die Grundlagen der Charakterkunde (1926)

- Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele (1929–32)

See also

In Spanish: Ludwig Klages para niños

In Spanish: Ludwig Klages para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |