Mammoth steppe facts for kids

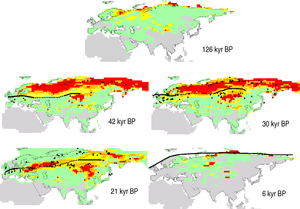

Imagine a huge, cold, and dry grassland that covered most of the northern part of the world! This was the mammoth steppe. It was Earth's largest natural area, called a biome, during the Last Glacial Maximum (the peak of the last Ice Age).

This vast grassland stretched from Spain across Europe and Asia, all the way to Canada. It reached from the Arctic islands down to China. The climate was very cold and dry. The land was covered mostly by tasty grasses, herbs, and willow bushes. Huge herds of animals like bison, horses, and woolly mammoth lived there. This amazing ecosystem lasted for about 100,000 years without big changes. But then, around 12,000 years ago, it almost completely disappeared.

Contents

What's in a Name?

Scientists started thinking about this ancient grassland in the late 1800s. Alfred Nehring and Jan Czerski suggested that large plant-eating animals lived across northern Europe during the last Ice Age. They believed the climate was like a steppe (a dry, grassy plain).

Later, in 1982, a scientist named R. Dale Guthrie gave this ancient region its special name: "mammoth steppe."

How the Mammoth Steppe Formed

The last glacial period, often called the 'Ice Age', lasted from about 126,000 to 11,700 years ago. This was the most recent cold period within our current ice age. It happened during the last part of the Pleistocene epoch.

This ancient Arctic environment was extremely cold, dry, and probably dusty. It was very different from the wet, swampy tundra we see in the Arctic today. The coldest part of this Ice Age was the last glacial maximum. During this time, huge ice sheets grew bigger from about 33,000 years ago. They reached their largest size around 26,500 years ago.

The ice began to melt in the Northern Hemisphere about 19,000 years ago. In Antarctica, it started melting around 14,500 years ago. This melting caused sea levels to rise quickly.

During the peak of the last glacial maximum, the huge mammoth steppe covered a massive area. It went from the Iberian Peninsula across Eurasia and over the Bering land bridge. This land bridge connected Asia to Alaska and the Yukon. The steppe stopped there because of the Wisconsin glaciation (a large ice sheet).

The Bering land bridge existed because so much of the Earth's water was frozen in ice sheets. This made sea levels much lower than they are today. When the ice started melting and sea levels rose, this land bridge disappeared under the water around 11,000 years ago.

During these cold periods, the climate was very dry. This was because so much water was locked up in glaciers. The mammoth steppe was like a giant "inner courtyard." It was surrounded by things that blocked moisture: huge continental glaciers, tall mountains, and frozen seas. These features kept rainfall very low. They also created more clear, sunny days than we have now. This led to more evaporation in summer, making it dry. In winter, warmth escaped into the night sky, making it very cold.

Scientists think seven main things caused this dry, cold environment:

- A very large and stable high-pressure system north of the Tibetan Plateau drove the climate in central Asia.

- The North Atlantic Current (part of the Gulf Stream) brought less warmth and moisture to Western Europe.

- The growing Scandinavian ice sheet blocked moisture from the North Atlantic.

- The North Atlantic Ocean surface froze, reducing moisture flow.

- Winter storms likely moved across Eurasia in a specific path.

- Lower sea levels exposed a huge flat plain in the north and east, making the continent much larger.

- North American glaciers protected Alaska and the Yukon from moisture.

All these physical barriers created a huge, dry area that stretched across parts of three continents.

Environment and Animals

The amount of animal life and plant growth on the mammoth steppe was similar to today's African savannah. There is no place quite like it on Earth today.

Plants of the Steppe

The environment changed over time. We know this from mammoth dung samples found in northern Yakutia. During warmer periods within the Ice Age, trees like alder, birch, and pine could survive in northern Siberia. However, during the coldest part of the Last Glacial Maximum, only treeless steppe plants grew.

As the Earth started warming up (around 15,000–11,000 years ago), shrubs and dwarf birch trees grew in northeastern Siberia. Later, during a cold snap called the Younger Dryas (12,900–11,700 years ago), open woodlands with birch and spruce appeared. By about 10,000 years ago, during the Holocene (our current warm period), patches of thick larch and pine forests grew.

Scientists once thought the mammoth steppe wasn't very productive. They believed its soils had little carbon. But these soils, called yedoma, were preserved in the permafrost of Siberia and Alaska. We now know they hold the largest amount of organic carbon on Earth! So, the mammoth steppe was actually a very productive place.

The plants were mostly tasty, fast-growing grasses, herbs, and willow shrubs. Herbs were much more common than they are today. They were the main food for the huge plant-eating mammals.

-

Artemisia (like mugwort), found in Taymyr lowlands (24,000–10,300 YBP), Yakutia (22,500 YBP), Alaska and Yukon (15,000-11,500 YBP)

-

Cyperaceae (sedges), found in Yakutia (22,500 YBP), Alaska and Yukon (15,000-11,500 YBP)

-

Salix (willow), found in Taymyr lowlands (24,000–10,300 YBP), Yakutia (22,500 YBP), Alaska and Yukon (15,000-11,500 YBP)

-

Rubus chamaemorus (cloudberry), found in Yakutia (22,500 YBP)

-

Larch, found in Taymyr lowlands (48,000–25,000 YBP, and later 9,400-2,900 YBP)

-

Betula nana (dwarf birch), found in Taymyr lowlands (48,000–25,000 YBP)

Animals of the Steppe

The mammoth steppe was home to many large animals. The most common were bison, horses, and the woolly mammoth. This area was where many of the Ice Age "woolly" animals developed.

Important meat-eating animals found across the mammoth steppe included the Panthera spelaea (cave lion), the wolf Canis lupus, and the brown bear Ursus arctos. The cave hyena lived in the mammoth steppe in Europe, but not in the main northern parts of Asia.

On Wrangel Island, scientists have found remains of woolly mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, horse, bison, and musk ox. While reindeer and small animals don't preserve well, reindeer droppings have been found in the soil. In the driest parts of the mammoth steppe, south of Central Siberia and Mongolia, woolly rhinoceros were common, but woolly mammoths were rare.

Today, reindeer live in northern Mongolia. Historically, their southern range reached Germany and the steppes of eastern Europe. This shows they once lived across much of the mammoth steppe. Mammoths survived on the Taimyr Peninsula into the Holocene. A small group of mammoths lived on St. Paul Island, Alaska, until about 3750 BC. The small mammoths of Wrangel Island survived even longer, until 1650 BC.

Some animals from the mammoth steppe, like bison in Alaska and the Yukon, and horses and muskox in northern Siberia, survived even after the mammoth steppe disappeared. One study suggests that a change in climate caused a big drop in mammoth numbers. This made them easier targets for human hunters. It's likely that both climate change and human hunting together led to the extinction of the woolly mammoth.

Why the Mammoth Steppe Disappeared

The mammoth steppe had a very cold and dry climate. During past warm periods between Ice Ages, forests and shrubs grew northward into the steppe. Areas like northern Siberia, Alaska, and the Yukon (called Beringia) became places where the mammoth steppe could still survive. When the planet got colder again, the mammoth steppe would expand. This ecosystem lasted for about 100,000 years, but then it suddenly vanished around 12,000 years ago.

There are two main ideas about why the mammoth steppe declined.

Climate Change Theory

The Climate Change Theory suggests that the huge mammoth ecosystem could only exist within a certain range of cold, dry conditions. At the start of the Holocene (our current warm period), about 10,000 years ago, mossy forests, tundra, lakes, and wetlands replaced the mammoth steppe.

Scientists believe that, unlike earlier warm periods, the climate became warmer and wetter. This change caused the grasslands to disappear. When the grasslands vanished, the large animals that depended on them also disappeared.

For example, the extinct steppe bison (Bison priscus) lived across northern Siberia until about 8,000 years ago. A study of a frozen steppe bison mummy found in northern Yakutia, Russia, showed it was a grazer. It lived in a habitat that was becoming filled with shrubs and tundra plants. Higher temperatures and more rainfall in the early Holocene reduced its grassland home. This led to groups of bison becoming separated, and eventually, they died out.

A 2017 study looked at the environment in Europe, Siberia, and the Americas from 25,000 to 10,000 years ago. It found that long warming periods, which led to melting glaciers and lots of rain, happened just before the grasslands changed. These grasslands, which supported huge plant-eating animals, turned into widespread wetlands with plants that were harder for them to eat. This study suggests that changes in moisture led to the extinction of many large animals. In Africa, grasslands could still exist between deserts and central forests, so fewer large animals went extinct there.

Human Hunting Theory

The Human Hunting Theory suggests that the huge mammoth ecosystem covered many different regional climates and wasn't greatly affected by climate changes. Its very productive grasslands were kept healthy by animals trampling down mosses and shrubs. Grasses and herbs that actively released water into the air were common.

At the start of the Holocene, rainfall increased, but temperatures also rose. So, the overall dryness of the climate didn't change much. This theory suggests that human hunting caused the number of large animals to drop. When there weren't enough animals to maintain the grasslands, forests, shrubs, and mosses grew more. This further reduced the animals' food supply.

The mammoth continued to live on isolated Wrangel Island until just a few thousand years ago. Also, some other large animals from that time still exist today. This suggests that something other than just climate change was responsible for the extinction of many large animals.

Evidence of mammoths hunted by humans 45,000 years ago has been found at Yenisei Bay in the central Siberian Arctic. Two other sites in northeast Siberia, dated between 14,900 and 13,600 years ago, also show signs of mammoth hunting. Tools found there are similar to those in northwest North America, suggesting a connection between ancient human groups.

Where It Still Exists Today

During the Holocene, species that liked dry conditions either died out or were limited to small areas. Today, cold and dry conditions similar to the last Ice Age can be found in the eastern Altai-Sayan mountains of Central Eurasia. This area hasn't changed much between the cold Ice Age and our current warm period.

Recent studies of ancient environments and pollen suggest that some parts of the Altai-Sayan mountains today are the closest thing to the mammoth steppe environment. This region's environment is thought to have been stable for the past 40,000 years. The eastern Altai-Sayan region is like a "refuge" from the last Ice Age.

Both during the Ice Age and today, the eastern Altai-Sayan region has supported large plant-eating and meat-eating animals. These animals are adapted to steppe, desert, and mountain environments. These areas haven't been separated by forests. None of the surviving Ice Age mammals live in temperate forests, taiga (boreal forests), or tundra today. Areas like Ukok-Sailiugem in the southern Altai Republic, and Khar Us Nuur and Uvs Nuur (Ubsunur Hollow) in western Mongolia, have been home to reindeer and saiga antelope since the Ice Age.

|

See also

In Spanish: Estepa de mamut para niños

In Spanish: Estepa de mamut para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |