Philadelphia in the American Civil War facts for kids

During the American Civil War, the city of Philadelphia was very important for the Union side. It provided many soldiers, money, weapons, and medical care. Philadelphia also supplied the Union army with many important items.

Before the war, Philadelphia had strong business connections with the South. This meant many people in the city understood the South's complaints. But once the war started, most Philadelphians changed their minds. They began to support the Union and the fight against the Confederate States. More than 50 groups of soldiers, both infantry (foot soldiers) and cavalry (horse soldiers), were formed in Philadelphia. The city was also the main place where uniforms for the Union Army were made. Factories in Philadelphia also built weapons and warships. Philadelphia was home to the two biggest military hospitals in the United States at the time: Satterlee Hospital and Mower Hospital.

In 1863, the Confederate Army threatened to invade Philadelphia during the Gettysburg Campaign. People built defenses to protect the city. However, the Confederate army was stopped at Wrightsville and at the famous Battle of Gettysburg. After the Civil War, the Republican Party became very strong in Philadelphia. Before the war, many people disliked the party because it was against slavery. But after the war, the Republican Party became so powerful that it controlled Philadelphia's politics for almost 100 years.

Contents

Philadelphia Before the War

Before the Civil War, Philadelphia was the second-largest city in the United States. Its strong business ties with the South meant many people in the city felt friendly towards the South. For example, some city leaders wanted to get rid of laws that might upset the South. Meetings were held where people discussed if Pennsylvania should side with the South if it left the Union. Many people blamed the Abolitionist movement, which wanted to end slavery, for the problems. Abolitionists in Philadelphia were often bothered and threatened.

In the 1860 election for mayor, the Democratic Party candidate, John Robbins, ran against the current mayor, Alexander Henry. Mayor Henry was part of the People's Party, which was linked to the national Republican Party. However, in Pennsylvania, they didn't talk much about slavery. Instead, their main focus was on protecting local businesses with tariffs (taxes on imported goods). During the election, the Democrat candidate attacked Henry's moderate views on slavery, saying he was almost an Abolitionist. Henry was re-elected, but some people said there were problems with the votes. In the election for governor, Philadelphia voted 51 percent for the Democrats. But in the presidential election that year, Abraham Lincoln of the Republican Party won 52 percent of the city's votes.

After the election, the Philadelphia City Council voted to invite Lincoln to speak in the city. Only one person voted against it. Lincoln accepted and gave two speeches. One was at the Continental Hotel, and the other was at the Pennsylvania State House. His speeches helped change the minds of many important people in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia During the Civil War

After the American Civil War officially started with the attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina, people's opinions in Philadelphia changed quickly. American flags and decorations appeared all over the city. Philadelphians turned their anger from Abolitionists to people who supported the South. A large crowd threatened the office of the Palmetto Flag, a newspaper that supported the South leaving the Union. The police and Mayor Henry stopped the crowd from causing damage, but the newspaper closed soon after. Other newspapers that favored the South also lost many readers. When The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the Union had lost the First Battle of Bull Run, which was different from what the government first said, a crowd threatened to burn down its office. Mayor Henry had to make another personal appearance to stop a riot at the home of William B. Reed, a well-known Democrat. Other people who were thought to support the South started displaying American flags to avoid trouble.

The excitement at the start of the war soon faded. However, people who criticized the war were still targeted. Around August 1861, federal authorities arrested eight people for showing sympathy for the Confederacy. Most of these people were released quickly. But one person, the son of William H. Winder, was held for over a year. Authorities also shut down a weekly newspaper that supported the South, called the Christian Observer. In 1862, Charles Jared Ingersoll, a former Democratic Representative, was arrested. He had spoken against the war and was accused of discouraging people from joining the army. This arrest of a respected politician caused embarrassment for local Republicans. He was released after direct orders from the federal government.

Democrats in the city used Lincoln's decision to stop habeas corpus (the right to be brought before a judge) and his Emancipation Proclamation (which declared many enslaved people free) to argue against Republicans. However, many people in Philadelphia agreed with The Philadelphia Inquirer. In a July 1862 article, the newspaper said that "in this war there can be but two parties, patriots and traitors." Democrats did not do well in the 1862 election. Democratic Representative Charles John Biddle lost to Charles O'Neill. This left only one Democrat from Philadelphia in the US House of Representatives. Samuel J. Randall, the only Democrat from Philadelphia in the House, was actually closer to Republicans than to his own party. Mayor Henry, running under the National Union Party, was elected for a third term as mayor of Philadelphia.

Threat of Invasion

In June 1863, General Robert E. Lee led his Confederate army into Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg Campaign. When news reached Philadelphia that the Confederate Army was marching towards Harrisburg, about 100 miles to the west, Philadelphians did not feel a strong need to prepare their city for defense. On June 26, Major-General Napoleon Jackson Tecumseh Dana took charge of the military area of Philadelphia. He began building defensive trenches with the help of volunteers recruited by Mayor Henry. At the beginning of July, Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin came to the city. He hoped to make the city realize the danger and prepare.

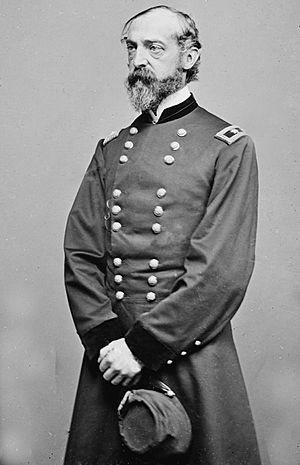

Philadelphia's Twentieth Pennsylvania Emergency Regiment and its First City Troop were among the local soldiers who helped stop the Confederate forces. They prevented the Confederates from crossing the Susquehanna River at Wrightsville by burning the Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge. The threat of invasion ended on July 3. On that day, Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was defeated by the Army of the Potomac, led by George Meade, in the three-day Battle of Gettysburg.

After Gettysburg

After the Gettysburg Campaign, support for the war grew stronger. Hopes for anti-war groups to gain power in the city faded. After the Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, patriotic feelings increased. More people joined the army. Philadelphia voted to re-elect Republican Governor Curtin instead of the Peace Democrat George Washington Woodward. In July 1863, the draft (forced military service) began in the city. Mayor Henry and General George Cadwalader, who replaced Major-General Dana, worked quietly to stop any problems. They wanted to prevent riots like the draft riots that happened in New York City.

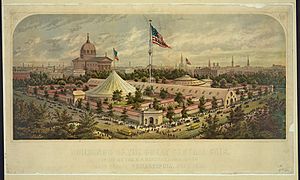

In June 1864, the Philadelphia branch of the United States Sanitary Commission organized a huge fair. Its goal was to raise money for bandages and medicine. The Great Central Fair lasted two weeks. It was held in temporary buildings that covered several acres of Logan Square. Thousands of artworks were borrowed for display, and many were given as donations for auction. President Lincoln was among the visitors. The Sanitary Fair raised an amazing $1,046,859.

In the 1864 election, most Philadelphians voted to re-elect Lincoln. They also voted for the four representatives from Philadelphia. The National Union Party also won the majority in both parts of the Philadelphia City Council.

In December 1864, Philadelphia's streetcar companies started allowing African Americans on their streetcars. Some companies even ran streetcars specifically for African Americans. The companies gave in to pressure from African Americans and others. This was because African American soldiers were often late for duty. Also, soldiers' wives had trouble visiting their wounded husbands in the hospitals. The city's streetcars were not fully integrated (open to everyone) until 1867. This happened when a law was passed by the Pennsylvania General Assembly requiring it.

Philadelphia's Military Contributions

Many soldiers from New England and New Jersey passed through Philadelphia on their way south. Many soldiers traveled through New Jersey by train on the Camden and Amboy Railroad. Then they crossed the Delaware River by ferry. The ferry would drop them off at Washington Avenue. From there, they would march to waiting trains of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad. Local residents formed two groups, the Union Volunteer Refreshment Saloon and the Cooper Shop Refreshment Saloon. These groups greeted arriving soldiers with food, drinks, and materials to write letters home.

The first Philadelphia regiment (a military unit) sent out of the city was a volunteer group called the Washington Grays. They were sent to help defend Washington, DC. This unit reached Baltimore, Maryland, where they were attacked by a crowd of people who supported the South in the Baltimore riot of 1861. The group retreated to Philadelphia. There, George Leisenring, a German-born private soldier, died. He became Philadelphia's first war casualty (someone killed or injured in war).

The first Philadelphians to fight Confederate forces were the Twenty-third Infantry Regiment and the First City Troop. They fought at the Battle of Hoke's Run in West Virginia. In the end, more than 50 infantry and cavalry regiments were formed either fully or partly in Philadelphia. These included the Philadelphia Brigade and the 118th Pennsylvania Infantry. The 118th Pennsylvania Infantry was created and supported by the Philadelphia Corn Exchange. In addition, 11 United States Colored Troops (African American military units) were organized in Philadelphia. During the war, between 89,000 and 90,000 Philadelphians signed up for military service. This number includes people who signed up more than once. It does not include African American soldiers from Philadelphia, whose enlistment numbers are not known.

Philadelphia's Schuylkill Arsenal was the main place where the US Army got its uniforms. Hundreds of workers in Philadelphia made parts of the uniforms in their homes. These parts were then put together at the arsenal. The Frankford Arsenal made ammunition (bullets and shells). The Sharp and Rankin's factory made special rifles that loaded from the back. The Philadelphia Navy Yard employed 3,000 people. It built 11 warships and prepared many more for battle. Philadelphia's private shipyards, like William Cramp & Sons, also built many ships, such as the USS New Ironsides.

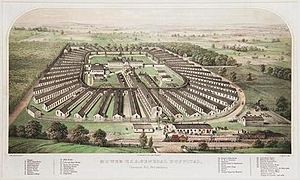

During the war, Philadelphia had 24 military hospitals. Philadelphia had as many as 10,000 beds for soldiers. This number does not include the beds in the 22 civilian hospitals, which sometimes also cared for soldiers. The Union Refreshment Saloon created the first military hospital in the city. Its hospital had 15 beds for sick soldiers who were passing through. Smaller hospitals, like Haddington Hospital and Citizens' Volunteer Hospital, each with 400 beds, were among the first to be set up. These were eventually closed so that more attention could be given to Philadelphia's largest military hospitals. These hospitals were the biggest military hospitals in the United States. They were Satterlee Hospital with 3,124 beds and Mower Hospital with 4,000 beds. In total, about 157,000 soldiers and sailors were treated in Philadelphia hospitals.

What the War Left Behind

The Civil War led to many years of the Republican Party being in charge of the city's politics. Before the war, Republicans had little support in Philadelphia. This was mainly because the party was against slavery. However, the Democrats' opposition to the war caused so many people to switch their support to Republicans during and after the war. This allowed a powerful, and later corrupt, political machine to be created. This machine would control city politics for almost a century.

In 1861, a group of important Philadelphians started the Union Club. They did this because another social club, the Wistar Club, had members who supported the South. The Union Club became the Union League in 1863 and removed its limit of 50 members. By the end of the war, it had 1,000 members. The Union League became a key place for Republican politics. It still exists today as one of Philadelphia's largest and most respected social clubs.

The Civil War also helped some of Philadelphia's upper class become wealthy. The Philadelphia banker Jay Cooke made a huge fortune selling Union war bonds, which were like loans to the government. These bonds were worth about $1 billion. The future streetcar owner Peter Widener got his first wealth by supplying meat to the Union Army. John and James Dobson became rich by making blankets for the soldiers.

War Memorials

The Civil War Library and Museum, now called the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia, was started in 1888. It is the oldest Civil War organization in America. This museum collects records, items, and other things related to the Civil War and the Underground Railroad (a network that helped enslaved people escape).

On the Benjamin Franklin Parkway is the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial. It was designed by Hermon Atkins MacNeil and finished in 1927. The memorial has two tall stone structures, each about 40 feet (12 meters) high. They sit on each side of the parkway.

Across 20th Street, there is the All Wars Memorial to Colored Soldiers and Sailors. This memorial was created in 1934 by J. Otto Schweizer. It was first put up in West Fairmount Park. In 1994, it was moved to Logan Circle.

Philadelphia's largest Civil War monument is the Smith Memorial Arch. It was built on the land where the 1876 Centennial Exposition (a big world's fair) used to be in West Fairmount Park. It was designed by James H. Windrim and finished in 1912. It includes sculptures by many famous artists.

Famous People from Philadelphia

The Philadelphia area was the birthplace or long-time home of several Union army generals and naval admirals. The city's most celebrated war hero was Major General George G. Meade (1815–1872). He became famous in the city for his success at the Battle of Gettysburg. He also commanded the Army of the Potomac, a major Union army. Philadelphia celebrated returning war heroes and Civil War veterans with parades. On June 10, 1865, the city held a huge parade. Meade led veteran soldiers through the city to a dinner at a volunteer refreshment saloon. Another big parade for Civil War veterans was held as part of the Independence Day celebration in 1866. This parade was led by another war hero from Philadelphia, Winfield Scott Hancock (1824–1886).

Other generals from Philadelphia included:

- George B. McClellan (1826–1885)

- Andrew A. Humphreys (1810–1883)

- David B. Birney (1825–1864)

- John Gibbon (1827–1896)

- George A. McCall (1802–1868)

- George Cadwalader (1806–1879)

- Joseph Barnes (1817–1883)

- Robert Patterson (1792–1881)

- Charles F. Smith (1807–1862)

- Thomas L. Kane (1822–1883)

Fifty-four soldiers and sailors from Philadelphia received the Medal of Honor. This is the highest military award given by the United States. Some of them were Sergeant Richard Binder, Captain Henry H. Bingham, Captain John Gregory Bourke, Captain Cecil Clay, Private Richard Conner, Quartermaster Thomas Cripps, Captain Frank Furness, Sailor Richard Hamilton, Coal Heaver William Jackson Palmer, Captain Forrester L. Taylor, and Fireman Joseph E. Vantine.