Pierre Le Gros the Younger facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pierre Le Gros

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Pierre Le Gros the Younger

(anonymous drawing, early 18th century; unknown location) |

|

| Born | 12 April 1666 Paris

|

| Died | 3 May 1719 (aged 53) Rome

|

| Resting place | San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Sculptor |

| Style | Baroque |

Pierre Le Gros (born April 12, 1666, in Paris – died May 3, 1719, in Rome) was a famous French sculptor. He spent almost all his working life in Rome, Italy. For nearly 20 years, he was the most important sculptor there.

Pierre Le Gros created huge sculptures for important religious groups like the Jesuits and the Dominicans. He was involved in two of the biggest art projects of his time. These were the Altar of Saint Ignatius of Loyola in the Gesù church and the 12 giant Apostle statues in the Lateran basilica.

His amazing skill with marble attracted powerful people. These included Lorenzo Corsini, who later became Pope Clement XII, and Cardinal de Bouillon, a very high-ranking cardinal. Le Gros also worked on smaller, beautiful projects. Examples are the chapel of the Monte di Pietà and the Cappella Antamori in San Girolamo della Carità. These are like hidden treasures of Roman art.

Le Gros was known for his lively and dramatic Baroque style. However, he eventually faced a challenge from a more traditional, classicist art style. Despite his efforts, he couldn't keep his style as the most popular one.

Contents

About Pierre Le Gros's Name and Family

Pierre Le Gros always signed his name as Le Gros. This is how he was known in all official papers. However, in the 1800s and 1900s, people often started spelling his name Legros. To tell him apart from his father, who was also a famous sculptor named Pierre Le Gros the Elder, scholars often call him 'the Younger' or 'Pierre II'. His father worked for the French king Louis XIV.

Le Gros was born in Paris into a family of artists. His mother, Jeanne, died when he was three. But he stayed close to her brothers, Gaspard and Balthazard Marsy, who were also sculptors. He often visited their workshop and took it over when he was 15. His father taught him how to sculpt. He learned drawing from the engraver Jean Le Pautre, who was his stepmother Marie Le Pautre's uncle. His half-brother, Jean (1671–1745), became a portrait painter.

Pierre Le Gros as a Student

As a student at the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture), Le Gros won the important Prix de Rome award. This allowed him to study at the French Academy in Rome. He arrived there in 1690. In Rome, he became good friends with his cousin Pierre Lepautre, who was also a sculptor. He also befriended Gilles-Marie Oppenordt, an architect who was also studying there.

His time at the academy from 1690 to 1695 was productive but had its problems. The academy often had money troubles. Also, the building where they worked, the Palazzo Capranica, was quite old and falling apart. It was not as grand as the academy's later homes.

Le Gros really wanted to show his skills by carving a marble copy of an old statue. After a lot of effort, he finally got permission. The director of the academy, Matthieu de La Teulière, and his boss in Paris, Édouard Colbert de Villacerf, approved it. He copied a statue called Vetturie, which was in the garden of the Villa Medici in Rome. Le Teulière chose it as a good example of Roman women's clothing. Le Gros even improved the dress details based on drawings by Raphael. He finished the statue in 1695. It was sent to Marly about 20 years later and then to Paris in 1722, where it was placed in the Tuileries Garden.

Early Independent Works

The Chapel of Saint Ignatius

In 1695, Le Gros entered a competition. He wanted to create a marble sculpture for the altar of Saint Ignatius of Loyola. The Jesuit Order was building this altar in their main church in Rome, Il Gesù. This project became the most ambitious and important sculpture work in Rome for many years. The altar's design was by Andrea Pozzo. Pozzo also made paintings of the sculptures to guide the artists, but he let the sculptors add their own details.

Triumph of Faith over Idolatry

Religion Overthrowing Heresy and Hatred

Religion Overthrowing Heresy

Le Gros's involvement was kept secret at first. Only after he got the job was he allowed to tell the French Academy's director. The director was surprised and a bit upset that Le Gros hadn't told him sooner. But he was also proud that his former student had beaten the best sculptors in Rome. He noted that the models submitted by the older sculptor Jean-Baptiste Théodon needed many changes. But Le Gros's model was perfect from the start.

Le Gros's sculpture was called Religion Overthrowing Heresy. It was a dramatic group of four large marble figures on the right side of the altar. The tall figure of Religion, representing the Catholic faith, drives out heresy. Heresy is shown as an old woman tearing her hair and a falling man with a snake. To make it clear who the heretics were, three books have the names of Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli. A small angel (called a putto) tears apart Zwingli's book. Le Gros based the faces on drawings by Charles Le Brun that showed different emotions.

This work is often compared to Théodon's sculpture, Triumph of Faith over Idolatry. Théodon's style was much more traditional and stiff. The competition between these two French artists continued for several years. Le Gros's amazing skill in this sculpture launched his career. He became very popular and was the busiest sculptor in Rome at that time.

Silver Statue of St. Ignatius

In 1697, with his first group almost finished, Le Gros won another competition. This time, it was for the main statue of the altar: a silver statue of St. Ignatius. It was a unique competition because the 12 sculptors had to choose the best model from their rivals themselves. When Le Gros was announced as the winner, his French friends were overjoyed. They carried him through the streets in celebration.

The statue was cast in silver by Johann Friedrich Ludwig and finished in 1699. About 100 years later, in 1798, it was sadly destroyed. During the Roman Republic, the head, arms, legs, and angels were melted down for their silver. Le Gros's chasuble (a type of robe) was saved. The missing parts were remade with silver-coated plaster from 1803–04, supervised by Antonio Canova.

Other Early Works for Jesuits and Dominicans

At the same time, Le Gros was busy with another big project for the Jesuits. He created a large altar relief called the Apotheosis of the Blessed Luigi Gonzaga in the church of Sant'Ignazio (1697–99). This altar was also designed by Pozzo. Le Gros had a lot of freedom to develop the design. He carved the figure of the saint almost completely in the round, making it stand out. The statue of the saint was polished very smoothly, making it look bright white. This made it the focus of the detailed relief.

He also began a lot of work for Antonin Cloche, the leader of the Dominicans. Cloche was French, like Le Gros. He was probably introduced to the sculptor by his secretary, Baptiste Monnoyer, a painter and Dominican friar who was Le Gros's friend. Cloche asked Le Gros to create the Sarcophagus for Pope Pius V (1697–98). This sarcophagus, made of green marble, was placed in the existing papal tomb in Santa Maria Maggiore. Its main purpose was to hold the saint's body and allow people to see it on special occasions. Usually, it was covered by a gilded bronze flap with a shallow image of the Pope.

To handle all these projects, Le Gros needed assistants and a good workshop. With help from the Jesuits, he found a perfect space in 1695 in a back part of the Palazzo Farnese. He used this workshop for the rest of his life.

High Hopes for New Projects

All of Le Gros's work as an independent artist had a clear deadline: the celebrations for the Holy Year 1700.

Married Life

In 1701, Le Gros married Marie Petit from Paris. She died in June 1704, leaving Le Gros with their first son (a second son lived only for a week). He needed a mother for his child, so he quickly remarried in October 1704. His new wife was another French woman, Marie-Charlotte. She was the daughter of René-Antoine Houasse, who was the director of the French Academy in Rome at the time. Nicolas Vleughels, who lived at Le Gros's studio, was a witness at the wedding. Pierre and Marie-Charlotte had two daughters and a son. This son's godfather was Filippo Juvarra in 1712. These children lived to be adults, but Le Gros's first son with Marie Petit died as a child in 1710.

Pope Clement XI

At the end of 1700, Cardinal de Bouillon, as the longest-serving cardinal, had the honor of making his friend, Giovanni Francesco Albani, the new Pope Clement XI. The new Pope loved art, and Le Gros felt this was a great time to aim high with his work.

Le Gros was elected a member of the Accademia di San Luca (Academy of Saint Luke) in 1700. In 1702, he presented a clay relief called The Arts Paying Tribute to Pope Clement XI as his special entry piece. This flattering scene showed his great hopes for the new Pope's support of the arts.

Antonin Cloche as a Patron

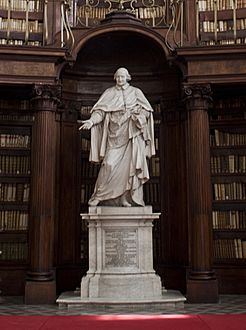

Le Gros remained the favorite sculptor of Antonin Cloche, who wanted to raise the status of the Dominicans. Cloche's friend, Cardinal Girolamo Casanate, died and left his large book collection and money to the Dominicans. So, Le Gros was asked to create the cardinal's tomb in the Lateran Basilica (1700–03). Later, he made the Statue of Cardinal Casanate for the Biblioteca Casanatense (1706–08), a library.

When the new Pope offered the many niches in Saint Peter's to different religious orders for statues of their founders, Cloche quickly asked Le Gros to sculpt the Statue of Saint Dominic (1702–06). This statue shows Le Gros's energetic and mature style. Since other religious orders were not in a hurry, Saint Dominic was the very first and for many decades the only large statue of a founder in Saint Peter's.

Other Important Commissions

Le Gros also continued to work for different parts of the Jesuit order. One such work was the statue of St Francis Xavier (1702) in the church of Sant'Apollinare, Rome. It is described as "a marvel of delicate marble work." The statue shows the saint reunited with his beloved crucifix. A crab had brought it back to him after he lost it in the sea. An earlier clay model showed the missionary looking much fiercer, perhaps preaching. But for the church, Le Gros chose a calmer pose.

Also in 1702, the leaders of the Monte di Pietà in Rome, led by Lorenzo Corsini, decided to continue decorating their chapel. They wanted two large reliefs for the side walls. They chose Le Gros to carve Tobit Lending Money to Gabael. His rival, Théodon, created the matching piece, Joseph Distributing Grain to the Egyptians, on the opposite wall (both 1702–05).

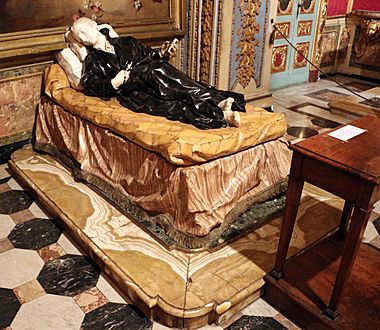

Stanislas Kostka

The colorful statue of Stanislas Kostka on his Deathbed (1702–03) is Le Gros's most famous work today. Usually, Le Gros made his sculptures look realistic by polishing white marble very finely. So, this multi-colored, tableau-like statue is quite unusual for him. In fact, it's unique in the history of sculpture.

The statue was made to create strong emotions in visitors. It is placed in the room where the blessed Jesuit student died, next to a chapel in the Jesuit novitiate at Sant'Andrea al Quirinale. The Pope himself visited this new holy site in 1703, walking there the day after it opened.

The statue still moves people today. Much of its effect comes from how it is displayed. This site is not something you just stumble upon. You have to seek it out. Visitors enter the quiet, dimly lit rooms carefully, feeling a sense of wonder. Then they see the striking shape of a life-sized figure lying still on a bed, which they can approach closely.

It's amazing that visitors often say Kostka looks so real, even though the statue is very artificial. His head, hands, feet, and pillows are made of white Carrara marble. His thin shirt is made of a different white stone. His habit (robe) is made of a black stone called "paragone" at the time. The saint's head would have originally had a halo. He held an image of the Madonna in his left hand, and a large crucifix would have extended from his right hand. Stanislas would have been looking at the crucified Christ with eyes already hazy. Without the large crucifix, an important meaning is lost today. The mattress, bed cover with bronze fringes, and bed step are made from colorful decorative stones. These were common in Roman Baroque art but used here in a very original and effective way.

Bouillon Monument

After 1697, Emmanuel-Théodose de La Tour d'Auvergne, cardinal de Bouillon hired Le Gros. He wanted a monument for his family to be placed in a burial chapel at Cluny Abbey. The cardinal was the abbot of Cluny Abbey. Bouillon might have known Le Gros through the Jesuits, as he often stayed as their guest. Le Gros finished the work by 1707, and it arrived in Cluny in 1709. He worked on this project in a very French style. He created a spectacular tomb monument that continued French Baroque traditions while also introducing new ideas.

The chapel was meant for several family members, including the cardinal himself. But it was mainly for his parents, Frédéric Maurice de La Tour d'Auvergne, Duc de Bouillon and Éléonor de Bergh, Duchesse de Bouillon. They are the main figures in the center of the monument. Their poses show that Éléonor helped her husband convert to Catholicism. Another important part was the heart of the duke's brother, Turenne, a national hero. His heart was in a heart-shaped container of gilded silver. A young angel carried it towards heaven from a white marble tower. This tower linked the family name La Tour to the biblical tower of David. The monument's message was that the family had royal status and sovereignty dating back to the 800s.

However, this unique monument did not influence other tomb sculptures. Royal officials inspected the sculptures to see if they made any overly proud family claims. But the sculptures were never even unpacked in Cluny. This was because Cardinal de Bouillon had a big disagreement with his cousin, the Sun King (Louis XIV). The cardinal was declared an enemy of the state, and all construction stopped. Le Gros's marble and bronze sculptures were stored in their sealed crates for nearly 80 years. After the French Revolution, they were almost sold as building material along with Cluny Abbey. But Alexandre Lenoir saved them for his museum, the Musée des Monuments français.

The lively marble figures of the Duke and Duchess de Bouillon, along with the angel (without Turenne's heart), and a detailed relief showing the duke as a battle hero, never made it to Paris. Today, they are at the Hôtel-Dieu in Cluny. A piece of the heraldic tower is kept in the abbey's granary.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

San Giovanni in Laterano

Lateran Apostles

At the end of 1702, Pope Clement XI announced his plan to fill the huge niches in the Lateran basilica with 12 large statues of the Apostles. These niches were designed by Borromini. The Pope's idea was similar to filling the niches in St. Peter's: get the church decorated, but have others pay for it. So, he asked church leaders and princes to pay for individual statues. He gave the job of choosing sculptors to a special committee. The Pope himself decided to pay for the statue of St. Peter and hired Théodon for it.

Like Théodon, Le Gros was given two statues to create: Saint Bartholomew (1703–12), paid for by the Pope's treasurer Lorenzo Corsini, and Saint Thomas (1703–11), paid for by King Peter II of Portugal.

From the beginning, it was important that all the Apostle statues looked unified. The architect Carlo Fontana advised on the correct size for the sculptures. More importantly, the aging painter Carlo Maratti, who was the Pope's favorite artist, was given the job of making sure the styles matched. He prepared drawings for each statue, which were given to the sculptors as a guide. This made many sculptors angry. In 1703, they complained. Théodon even quit because of it, eventually returning to France in 1705.

Le Gros went a step further. He decided to challenge Maratti's authority. He submitted a model for Saint Thomas (around 1703–04) that was very different from Maratti's calm, traditional style. Le Gros's model was the most detailed clay sculpture he ever made. It was inspired by the emotional Baroque style of Gianlorenzo Bernini's St. Longinus. Le Gros knew that if his model was accepted by the Pope's committee, all the other sculptors would have to follow his style. So, this was Le Gros's attempt to become the artistic leader of the Eternal City.

However, his model was not approved. The more traditional Late Baroque style won out. While Le Gros was the only sculptor who wasn't forced to work from Maratti's drawings, he had to change his design. The final marble statue of Saint Thomas is essentially the same figure, but every dramatic detail was smoothed out. The drapery (clothing folds) is more orderly, the head lost its intense look, the messy pages of the book became a carpenter's square, the rough rock became a flat base, the old tombstone became perfect, and the little angel disappeared. A lively group of a saint with an angel in a landscape became a solid statue in a niche.

Even though Le Gros was put in his place, he wasn't completely defeated. When it seemed that the Florentine sculptor Antonio Andreozzi wouldn't finish his Saint James the Greater, efforts were made in 1713 to get King Louis XIV to pay for Le Gros to do it. But it didn't happen.

Later Works

From 1708–10, Le Gros worked with his close friend, the architect Filippo Juvarra. They created the Cappella Antamori in the church of San Girolamo della Carità, Rome. Le Gros's statue of San Filippo Neri is placed in front of a large, colored glass window that is lit from behind. This makes the statue seem to glow in a warm yellow-orange light. Drawings by both Le Gros and Juvarra show that they both helped find the right design for the sculpture, trying many different poses. Le Gros also made many small angels (putti and cherubim) and two plaster reliefs for the ceiling. These reliefs showed scenes from Neri's life. This beautifully crafted chapel is one of the few examples of Juvarra's work in Rome.

Le Gros's last work for the Jesuits was the huge, grand Monument to Pope Gregory XV and cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi in Sant'Ignazio, created between about 1709–14. This monument combines the tombs of both the Pope and his cardinal-nephew. It celebrates their achievements from a Jesuit point of view. The inscription explains: ALTER IGNATIUM ARIS. ALTER ARAS IGNATIO (one raised Ignatius to the altars, the other erected altars for Ignatius). This means that Gregory made Ignatius a saint, and Ludovico built the church of Sant'Ignazio. The design is very dramatic. A large curtain (made from colored marble) is pulled back by two Famae (figures representing fame). These figures were made by Pierre-Étienne Monnot based on Le Gros's designs. The curtain hides the wall behind it, making the monument look like it stands freely, which is rare for wall tombs. The design also uses the monument's location next to a side entrance to the church. Several figures turn towards visitors entering from there, inviting them in. This effect is hard to see today because the door is no longer used.

From 1711–14, Le Gros worked on the Cappella di S. Francesco di Paola in San Giacomo degli Incurabili. For this project, Le Gros was the architect, meaning he was in charge of all the decorations. He also sculpted a large relief showing the saint adoring an old, respected image of the Madonna and child, who helps to cure the sick.

Decline in Rome

In 1713, Le Gros upset the Jesuits. He kept insisting on moving his own statue of Stanislas Kostka on his Deathbed into the church of Sant'Andrea al Quirinale. He wanted it to be the main piece for the newly decorated chapel of Saint Stanislas. At the same time, the decision for the last Lateran apostle statue was stuck. It seemed there were three main artists: Le Gros, Angelo de' Rossi, and Rusconi. Rusconi had already made three apostles and was clearly favored by Pope Clement XI, but no final decision was made.

In 1714, Le Gros's father died in Paris. Le Gros himself was very ill, suffering from gallstones.

Visit to Paris

To have an operation and to sort out his inheritance, Le Gros traveled to Paris in 1715. He stayed with his good friend Pierre Crozat. Crozat, who was very rich, helped arrange his travel on a royal ship. Crozat was a famous collector and supporter of the arts. His house was a hub for artists and art lovers. There, Le Gros would have met the older artist Charles de la Fosse and the young artist Antoine Watteau. Le Gros also reconnected with his friends Oppenordt and Vleughels. Crozat asked Le Gros to decorate a small room in his Paris house and the chapel in his beautiful country home, the Château de Montmorency (both are now destroyed).

Crozat and Oppenordt were well-connected with the Regent (the ruler of France at the time). So, Le Gros would have had a good start if he had decided to stay in Paris. He also helped Crozat in his long talks (1714–21) to buy the art collection of Queen Christina of Sweden for the regent.

However, Le Gros had big problems with the art establishment in Paris. The Royal Academy would not easily accept him, even though he was an internationally famous artist. Feeling rejected, Le Gros returned to Rome in 1716.

Return to Rome

Back in Rome, the last sad part of his life began. His absence had given an easy excuse to give the last Lateran apostle statue to Rusconi. The reason given was that de' Rossi had died, Le Gros was abroad, and so Rusconi was the only good sculptor available.

What happened at the Accademia di San Luca was even more serious. In 1716, a protest arose against new rules of the academy. These rules treated non-members unfairly financially. Francesco Trevisani and three other academy members disagreed with these new rules. Le Gros sided with them when he returned. As a result, all five were expelled from the academy. This meant they could no longer get public art jobs in Rome on their own.

The rich Roman art market was closed to Le Gros. He had to take on a few jobs outside of Rome. The Benedictine abbey of Montecassino had first contacted him in 1712. In 1714, he agreed to create three statues for the abbey's Chiostro dei Benefattori at a low price. These became his main focus. When he died, the statue of Pope Gregory the Great was finished. Emperor Henry II only needed a few finishing touches. The third statue, Charlemagne, was barely started. Le Gros's loyal assistant Paolo Campi finished it as his own work. During the heavy bombing of Montecassino in World War II, Pope Gregory was almost completely destroyed and is now heavily restored. Henry II was less damaged and can still be recognized as a work by Le Gros.

Thanks to his friend Juvarra, who was then the architect for the Duke of Savoy, Le Gros created two female saints for Juvarra's facade of the church of S. Cristina in Turin (around 1717–18). When they arrived, the statues of Saint Christina and Teresa of Avila were considered too beautiful to be left outside. They were moved inside the church (and later to Turin Cathedral in 1804). Copies made by a local sculptor replaced them on the facade. This was a great compliment, similar to how Bernini's angels for Ponte Sant'Angelo were honored half a century earlier.

In a letter from January 6, 1719, to Rosalba Carriera, Crozat described Le Gros as "without question the best sculptor there is in Europe, and the most honest man and the most endearing there is."

While Le Gros's great talent was recognized elsewhere, he waited in vain for similar praise in Rome. Rusconi received a knighthood from Clement XI for his work on the Lateran project in late 1718, but Le Gros received nothing.

Pierre Le Gros died from pneumonia half a year later, on May 3, 1719. He was buried in the French national church in Rome.

Only in 1725, when the painter Giuseppe Chiari was the head of the academy, were the five expelled artists brought back as members of the Accademia di San Luca. Four of them were brought back after their deaths, as only Trevisani was still alive.

Why Pierre Le Gros Was Important

Today, Le Gros is mostly forgotten. This is true for almost all artists who worked in Rome during his time. After many years of critics disliking the Baroque period, Gianlorenzo Bernini, Francesco Borromini, and a few other 17th-century artists are now seen as artistic geniuses. But even the great Alessandro Algardi, while respected by art historians, isn't widely known by the public. Even less known are the artists who came after them, like Maratti, Fontana, Le Gros, and Rusconi. However, during their lifetimes, they were considered outstanding artists across Europe. Young artists for generations looked up to them as examples.

Looking at Le Gros's work fairly, he was a very influential artist in an international art scene. While his family life was very French, his close friends included painters like the Dutch Gaspar van Wittel, the Frenchmen Vleughels and Louis de Silvestre, and the Italian Sebastiano Conca. He also befriended architects like the Italian Juvarra and the Frenchman Oppenordt, and sculptors like Angelo de' Rossi, as well as his loyal students Campi and Gaetano Pace.

Over the years, many young sculptors and painters from all over Europe came to work in his studio as assistants. These included the Englishman Francis Bird and the Frenchman Guillaume Coustou before 1700. Both later became important artists in their home countries. In the 1710s, the German painter Franz Georg Hermann and the very young Carle van Loo studied drawing with Le Gros in his workshop.

Le Gros's style also spread through his students. Copies of his important statues, like his St. Dominic, St. Ignatius, or the Apostle Bartholomew, can be found across Europe. Drawings of his Luigi Gonzaga and Stanislas Kostka were also widely shared. Le Gros's influence continued even after his death. His works were studied much later, as seen in sketches by Edme Bouchardon. Even in the late 1700s, art experts in Paris described his Vetturie as an amazing masterpiece, better than the ancient original. So, Le Gros's importance for European art in the 18th century is clear.

However, because he worked almost only in Rome, he didn't directly affect French art of his time. His French artist friends would have heard about him but wouldn't have seen his works. His student work, Vetturie, arrived in France 20 years late. The Bouillon Monument wasn't even unpacked until the end of the 1700s, so no one knew about it. Also, the dramatic style of Le Gros's work might not have been popular in Versailles, just as Bernini's style wasn't in the 1660s.

At the same time, his art cannot be called purely Italian. His art training at the Royal Academy and his experience in his father's and uncles' workshops gave him a unique starting point. He built on this experience and combined it with his admiration for Bernini's dramatic Baroque style. His love for fine details was something he shared with older French sculptors like François Girardon and Antoine Coysevox. Le Gros carefully studied all the art around him. He found ideas from less famous sculptors like Melchiorre Cafà and Domenico Guidi, and painters like Giovanni Battista Gaulli. He adapted these ideas for his own work, often changing them so much that the original source is hard to spot. There were only a few artists in early 18th-century Rome who worked in a similarly playful style as Le Gros. These included Angelo de' Rossi, Bernardino Cametti, and Agostino Cornacchini. But the art world was moving more and more towards classicism, making their style less common.

Le Gros's Artistic Style

Le Gros often designed his sculptures to look like a relief (a sculpture that sticks out from a flat surface). For his artistic approach, the overall shape and appearance were more important than how the mass and space were distributed. While the details and large forms are very three-dimensional, their volume is usually arranged in layers. This doesn't mean you can only view them from one angle. In fact, Le Gros designed his compositions to extend into space, inviting the viewer to walk around the figure. While a classicist sculptor like Rusconi linked how a sculpture moved in space to the human body, Le Gros achieved this with lots of flowing drapery (clothing) and dramatic gestures.

He also had a great sense for subtle effects of light and shadow. For example, he made the highly polished, snow-white figure of Luigi Gonzaga stand out. Or he cast Filippo Neri into a mysterious shade. All of Le Gros's work is characterized by how it looks from far away and up close. It's worth getting very close to even his largest figures to see the details.

Gallery

Chronological gallery of most of the major works by Le Gros not already illustrated - some dates are uncertain or overlap, therefore the sequence is only roughly chronological.

-

Angels and putti above the statue of Saint Sebastian by Paolo Campi, c. 1717–1719, Rome, Sant'Agnese in Agone

See also

In Spanish: Pierre Legros el Joven para niños

In Spanish: Pierre Legros el Joven para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |