Russian–American Telegraph facts for kids

The Russian–American Telegraph, also also known as the Collins Overland Telegraph, was a huge project by the Western Union Telegraph Company. From 1865 to 1867, they tried to build a telegraph line all the way from San Francisco in California to Moscow in Russia.

This amazing plan aimed to connect North America and Europe. The telegraph line was supposed to go through Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and Alaska (which was then called Russian America). Then, it would cross the Bering Sea underwater. After that, it would stretch across the vast Eurasian Continent to Moscow. From there, it would link up with existing lines across Europe.

This project was a very long alternative to laying a deep underwater cable across the Atlantic Ocean. The idea was that crossing the narrow Bering Strait underwater would be much easier. However, building the line across Siberia turned out to be very difficult. At the same time, another project, the transatlantic cable led by Cyrus West Field, was successfully finished. Because of this, the Russian-American Telegraph project was stopped in 1867. Even though it didn't achieve its main goal, the expedition brought many benefits. It helped explore new regions and gather important information. Today, no communication cables cross the Bering Sea. Cables from North America to Asia go much further south across the Pacific Ocean, connecting through Japan.

Contents

Why They Wanted a Telegraph Line

By 1861, the Western Union Telegraph Company had already connected the eastern United States to San Francisco with electric telegraph lines. The next big challenge was to connect North America with the rest of the world.

Two important people in telegraph history were working on this challenge. One was Cyrus West Field, who wanted to lay an undersea cable across the Atlantic Ocean from North America to Europe. The other was Perry Collins, who suggested a different route. He wanted to build an overland line from the west coast of North America, across the Bering Strait, through Siberia, and all the way to Moscow.

Field's company had laid the first transatlantic cable in 1858. But it broke just three weeks later, and they couldn't fix it. Meanwhile, Perry Collins visited Russia. He noticed that Russia was making good progress extending its telegraph lines eastward across Siberia from Moscow.

When Collins returned to the United States, he shared his idea with Hiram Sibley, the head of the Western Union Telegraph Company. Collins proposed an overland telegraph line that would go through the northwestern states, the colony of British Columbia, and Russian Alaska. Together, they promoted this idea and gained a lot of support in the US, London, and Russia.

Getting Ready for the Big Project

On July 1, 1864, Abraham Lincoln, the President of the United States, gave Western Union permission to build the line from San Francisco to the British Columbia border. He also gave them the Saginaw, a steamship from the United States Navy. Other ships like the George S. Wright and the Nightingale were also used. A fleet of riverboats and schooners helped too.

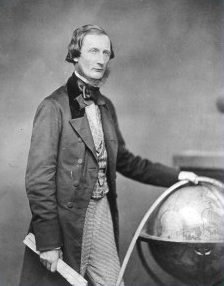

To manage the building work, Collins chose Colonel Charles Bulkley. He had been in charge of military telegraphs. Bulkley organized the workers into "working divisions" and an "Engineer Corps."

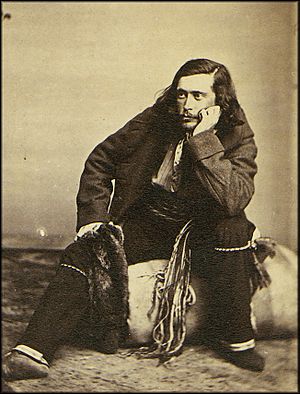

Edward Conway was put in charge of the American and British Columbia parts of the project. Franklin Leonard Pope was assigned to Conway and was responsible for exploring British Columbia. The job of exploring Russian America went to Robert Kennicott, a naturalist from the Smithsonian Institution. In Siberia, a Russian nobleman named Serge Abasa led the construction and exploration. He had help from Collins Macrae, George Kennan, and J. A. Mahood.

The exploration and building teams were divided into groups. One group worked in British Columbia. Another worked near the Yukon River and Norton Sound, with their main base at St. Michael, Alaska. A third group explored the area along the Amur River in Siberia. A fourth group of about forty men went to Port Clarence, Alaska to build the line that would cross the Bering Strait to Siberia.

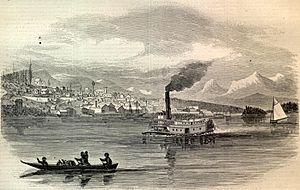

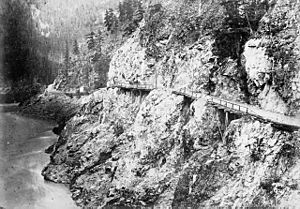

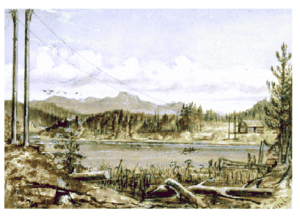

The Colony of British Columbia fully supported the project. They allowed all the materials for the line to be brought in without any extra taxes or fees. New Westminster was chosen as the main base in British Columbia. The city was very proud, as it was predicted to become a major communication hub. The path for the telegraph line followed the coast west from the US border. Then it went over high ground in what is now White Rock and South Surrey to the Nicomekl River. From Mud Bay, the line followed the Kennedy Trail northwest across Surrey and North Delta to the Fraser River.

At Brownsville, a cable was laid across the river to New Westminster. Surveying in British Columbia began before the line reached New Westminster on March 21, 1865. Edward Conway walked to Hope and was surprised by how difficult the land was. Because of Conway's concerns, British Columbia agreed to build a road from New Westminster to Yale. This road would meet the newly finished Cariboo Road. The telegraph company only had to string the wires along this new road.

Building Through Russian America

Work started in Russian America in 1865, but at first, they didn't make much progress. This was due to the difficult climate, the tough land, not enough supplies, and the construction teams arriving late. Still, the entire route through Russian America was surveyed by the fall of 1866. Instead of waiting for spring, which was normal, they started building and continued through that winter.

Many of the Western Union workers were not used to the harsh northern winters. Working in freezing conditions made putting up the line very hard. They had to light fires to thaw the frozen ground before they could dig holes for the telegraph poles. For moving around and hauling supplies, the only choice the work crews had was to use teams of sled dogs.

The men in the Russian American division didn't know that the Atlantic cable had been successfully completed until a whole year later. The first transatlantic message to England was sent in July 1866. By the time they found out, telegraph stations had been built. Thousands of poles were cut and placed along the route. Over 45 miles (72 km) of line had been finished in Russian America. Even with all this progress, the work was officially stopped in July 1867.

Building Through British Columbia

When the telegraph line reached New Westminster, British Columbia, in the spring of 1865, the first message it carried was about the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 15.

In May 1865, construction began from New Westminster to Yale. Then it followed the Cariboo Road and the Fraser River to Quesnel. Winter stopped the work, but it started again in the spring with 150 men working northwest from Quesnel.

In 1866, the work in that section moved quickly. Fifteen log telegraph cabins were built, and line was strung 400 miles (640 km) from Quesnel, reaching the Kispiox River and Bulkley Rivers. The company's sternwheeler ship, Mumford, traveled 110 miles (180 km) up the Skeena River from the Pacific Coast three times that season. It successfully delivered 150 miles (240 km) of material for the telegraph line and 12,000 food rations for its workers.

The line passed Fort Fraser and reached the Skeena River. This led to the creation of the settlement of Hazelton. It was there that they learned Cyrus West Field had successfully laid the transatlantic cable on July 27.

In British Columbia, the building of the overland line was stopped on February 27, 1867. The whole project was now considered unnecessary.

However, a useful telegraph system from New Westminster to Quesnel was left behind in British Columbia. This system was later extended to Barkerville, a town from the Cariboo Gold Rush. Also, a trail had been created through what was mostly unexplored wilderness.

The expedition also left behind a lot of supplies. Some of the First Nations people used these supplies well. Near Hazelton, Colonel Bulkley was impressed by the bridge the Hagwilget people had built across the Bulkley River. But he was careful and made sure it was reinforced with cable before his workers crossed it.

After the project was abandoned, the Hagwilgets at Hazelton built a second bridge using cable that the company had left behind. Both bridges were seen as amazing examples of engineering.

What the Project Left Behind

Even though the telegraph expedition was a big financial failure, it had some important long-term effects. It helped America expand its influence beyond its borders. It might have even sped up the US purchase of Alaska. The expedition was the first to study the plants, animals, and geology of Russian America. The people on the telegraph project played a key role in the purchase of Alaska. They provided valuable information about the land.

Meanwhile, the Colony of British Columbia could further explore, settle, and communicate with its northern areas more than the Hudson's Bay Company had done.

Many towns in Northwestern British Columbia can trace their first European settlements back to the Collins Overland Telegraph. Some examples are Hazelton, Burns Lake, Telkwa, and Telegraph Creek.

The expedition also helped set the stage for building the Yukon Telegraph line. This line was built from Ashcroft to Telegraph Creek and then to Dawson City, Yukon, in 1901.

Parts of the telegraph route became part of the Ashcroft trail. Gold seekers used this trail during the Klondike Gold Rush. Of all the trails used by the gold seekers, the Ashcroft was one of the toughest. Out of over fifteen hundred men and three thousand horses who left Ashcroft, British Columbia in the spring of 1898, only six men and no horses reached the goldfields.

Walter R. Hamilton was one of the few who completed the route. In his book The Yukon Story, he described the trail thirty years after it was abandoned: "All evidence of the right-of-way and poles were gone, but in a few instances we found pieces of old telegraph wire imbedded several inches in the spruce, jack-pine and poplar trees that had long-since grown up and over the wires that touched them. I found one of the old green glass insulators still attached to a galvanized wire. I kept it as a souvenir but lost it later with a camera and some clothing when a scow was nearly overturned on Lake Laberge."

Places Named After the Project

- Mount Pope in British Columbia was named after Franklin Pope. He was an Assistant Engineer and Chief of Explorations. He was responsible for surveying the 1,500-mile (2,400 km) section from New Westminster to the Yukon River.

- Kennecott, Alaska and the Kennicott Glacier are named after the expedition's naturalist, Robert Kennicott. Kennicott died during the expedition on May 13, 1866. His work was shared by William Healey Dall, another naturalist hired by Kennicott. This information and the news of Kennicott's death at age thirty-one helped William H. Seward, the United States Secretary of State, convince Congress to purchase Alaska from Russia in 1867.

- The Bulkley River, Bulkley Valley, Bulkley Mountains (now called the Bulkley Ranges), and the settlement of Bulkley House in British Columbia are named after Colonel Charles Bulkley. The Bulkley-Nechako Regional District, a local government in that area, gets its name from these places.

- Burns Lake was named after Michael Byrnes. He was a scout for the Collins Overland Telegraph plan. He explored the route from Fort Fraser to Skeena Forks (Hazelton, BC).

- Decker Lake was named after Stephen Decker, a construction foreman in British Columbia.

- The Telegraph Range in the Ootsa Lake area is one of several landforms whose name is connected to the project.

Books About the Expedition

Several important books tell the story of the expedition. The scientific travelogue by Smithsonian scientist William Healey Dall is often used as a reference. An English travelogue by Frederick Whymper also gives more information. Among personal stories, there is a diary by Franklin Pope.

George Kennan and Richard Bush both wrote about the difficulties they faced during the expedition. Kennan later became famous for changing American opinions about the Russian Empire. He was originally very supportive of Russian settlement in the Far East. But after visiting exile camps in the 1880s, he changed his mind. He later wrote Tent Life in Siberia: Adventures Among the Koryaks and Other Tribes in Kamchatka and Northern Asia. Richard Bush, trying to be as successful as Kennan, wrote "Reindeer, Dogs and Snowshoes".

All documents and books about the expedition are historically valuable. They offer insights into travel and discovery, and also into the cultures of the time. The descriptions of Indigenous peoples in places now known as British Columbia, the Yukon, and Alaska, as well as Eastern Siberia, show the attitudes of that era. Telegraph records provide evidence for native land claims, such as those of the Gitxsan Nation of northern British Columbia. Dall's records have helped find Smithsonian exhibits that were returned to their original Indigenous homes.

See also

In Spanish: Electrotelegrafía ruso-americana para niños

In Spanish: Electrotelegrafía ruso-americana para niños