Simon Newcomb facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Simon Newcomb

|

|

|---|---|

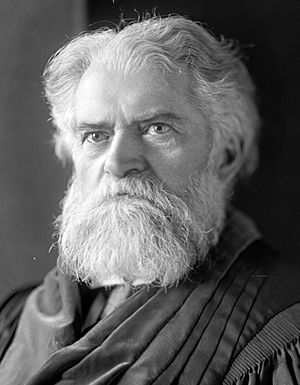

Newcomb c. 1905

|

|

| Born | March 12, 1835 Wallace, Nova Scotia, Canada

|

| Died | July 11, 1909 (aged 74) Washington, D.C., U.S.

|

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Citizenship | American |

| Alma mater | Harvard University (BSc, 1858) |

| Spouse(s) |

Mary Caroline Hassler

(m. 1863) |

| Children | 4, incl. Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee and Anna Josepha |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1890) Bruce Medal (1898) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy mathematician |

| Academic advisors | Benjamin Peirce |

| Doctoral students | Henry Ludwell Moore |

| Signature | |

Simon Newcomb (born March 12, 1835 – died July 11, 1909) was a very smart person who studied many things. He was a Canadian–American astronomer and mathematician. He taught math in the United States Navy and at Johns Hopkins University.

Even though Newcomb didn't go to a regular school much, he earned a science degree from Harvard in 1858. He helped a lot with how we keep time. He also worked on other math topics like economics (how money and goods work) and statistics (collecting and understanding data). He could speak several languages and wrote many popular science books. He even wrote a science fiction novel.

Contents

Simon Newcomb's Life Story

Early Years and Learning

Simon Newcomb was born in Wallace, Nova Scotia, Canada. His parents were John Burton Newcomb and Miriam Steeves. His father was a teacher who moved around a lot. This meant Simon didn't have much regular schooling. His father taught him instead.

When Simon was 16, he started working for a doctor named Dr. Foshay. This doctor used herbs to treat people. Simon was supposed to work for five years. But after two years, Simon realized Dr. Foshay wasn't very scientific. He left and walked about 120 miles (190 km) to Calais, Maine. From there, he sailed to Salem, Massachusetts, where his father had moved.

Around 1854, Newcomb joined his father. They traveled to Maryland together. Simon taught in Maryland for two years, from 1854 to 1856. He taught in country schools in Kent County and Queen Anne's County. In his free time, he studied many subjects. He especially loved math and astronomy. He read Isaac Newton's famous book Principia during this time.

In 1856, Newcomb became a private tutor near Washington, DC. He often went to the city to study math in libraries. He even borrowed a copy of a complex math book by Pierre-Simon Laplace.

Newcomb taught himself a lot about math and physics. He worked as a "human computer" at the Nautical Almanac Office in Cambridge, Massachusetts, starting in 1857. This meant he did many calculations by hand. At the same time, he studied at Harvard University. He earned his science degree in 1858.

Career in Astronomy

During the American Civil War, many people left the US Navy. In 1861, Newcomb got a job as a math professor and astronomer at the United States Naval Observatory in Washington D.C.. He started working on measuring where the planets were. This helped with navigation. He became very interested in how planets move.

In 1870, Newcomb visited Paris, France. He knew that the existing tables for the Moon's positions were wrong. He found older data from 1672 that could help. But he had to leave Paris quickly because of fighting during the Franco-Prussian War. He managed to escape the city during the riots. Newcomb used the new data to fix the Moon's position tables.

In 1875, he was offered a job to lead the Harvard College Observatory. But he said no. He preferred working with math and calculations over observing the sky with telescopes.

Leading the Nautical Almanac Office

In 1877, Newcomb became the director of the Nautical Almanac Office. With help from George William Hill, he started to recalculate all the main numbers used in astronomy. From 1884, he also worked as a demanding professor of mathematics and astronomy at Johns Hopkins University.

Newcomb worked with A. M. W. Downing to create a plan. This plan helped solve a lot of confusion about astronomy numbers around the world. In 1896, a meeting in Paris decided that everyone should use Newcomb's calculations. These were called Newcomb's Tables of the Sun. Even in 1950, another meeting confirmed that Newcomb's numbers were still the international standard.

Family Life

Simon Newcomb married Mary Caroline Hassler on August 4, 1863. They had three daughters and one son who died when he was a baby.

Newcomb passed away in Washington, D.C., on July 11, 1909. He had bladder cancer. He was buried with military honors. President William Howard Taft was there.

Newcomb's daughter, Anita Newcomb McGee (1864-1940), became a medical doctor. She started the Army Nurse Corps. She received awards for her work during the Spanish–American War and in Japan. She was buried next to her father with full military honors.

Another daughter, Anna Josepha, studied art. She was active in the movement for women's right to vote. She organized a meeting in 1912 to support voting rights for women.

Newcomb's Important Work

Measuring the Speed of Light

In 1878, Newcomb began planning to measure the speed of light very precisely. He thought this was important for getting exact values for many astronomy numbers. He was working on improving a method by Léon Foucault. Then he got a letter from Albert Abraham Michelson, a young naval officer who was also planning to measure the speed of light. This started a long friendship and working relationship.

In 1880, Michelson helped Newcomb with his first measurement. The instruments were at Fort Myer and the United States Naval Observatory. Michelson later started his own project. Newcomb did a second set of measurements between the observatory and the Washington Monument. Michelson published his first measurement in 1880. Newcomb's measurement was quite different. In 1883, Michelson changed his measurement to be closer to Newcomb's.

Benford's Law

In 1881, Newcomb found a cool math rule now called Benford's law. He noticed that in old logarithm books, the pages that started with "1" were much more worn out. This made him realize that in many lists of numbers, more numbers tend to start with "1" than with any other digit.

Chandler Wobble

In 1891, Seth Carlo Chandler discovered that the Earth wobbles a bit every 14 months. This is called the Chandler wobble. Newcomb quickly explained why this wobble happens. He said that the Earth is not perfectly stiff like a rock. It's a little bit flexible. Newcomb used the wobble to figure out how flexible the Earth is. He found it's a bit stiffer than steel.

Other Studies

Newcomb taught himself many things and was good at many subjects. He wrote about economics. His book Principles of Political Economy (1885) was praised by famous economist John Maynard Keynes. Newcomb was also the first to clearly explain the equation of exchange. This equation shows how money and goods are related in an economy.

He spoke French, German, Italian, and Swedish. He enjoyed mountaineering (climbing mountains) and read a lot. He also wrote many science books for the public. His science fiction novel was called His Wisdom the Defender (1900). Newcomb was also the first person to notice a natural glow in the night sky called Airglow in 1901.

Thoughts on Flying Machines

Newcomb is famous for saying he thought it was impossible to build a "flying machine." In an article called "Is the Airship Possible?", he wrote that it would need new discoveries. He thought it would need "some new metal or some new force."

In 1903, he wondered if people would have to give up trying to fly. He thought that if a person flew, they couldn't stop. He believed that if they slowed down, they would fall. Newcomb didn't understand how airfoils (like airplane wings) work. He thought an "aeroplane" was just a flat board. So, he concluded it couldn't carry a person's weight.

Newcomb was especially critical of Samuel Pierpont Langley's work. Langley tried to build a flying machine with a steam engine, but his attempts failed in public.

Newcomb didn't know about the Wright Brothers' work. They worked quietly. When Newcomb heard about the Wrights' successful flight in 1908, he quickly accepted it.

Newcomb thought that helicopters (rotating wing machines) and airships (like blimps) that float would be more successful. Within a few decades, large airships like the Graf Zeppelin were carrying passengers across oceans.

Awards and Honors

Simon Newcomb received many awards and honors for his work:

- He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences (1869).

- He won the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1874).

- He became a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (1875).

- He was a Fellow of the Royal Society (1877).

- He received the Huygens Medal (1878).

- He was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society (1878).

- He was president of the Philosophical Society of Washington (1878-1880).

- He was editor of the American Journal of Mathematics (1885–1900).

- He won the Copley Medal (1890).

- He was made a Chevalier of the Légion d'Honneur (1893) in France.

- He was president of the American Mathematical Society (1897–1898).

- He won the Bruce Medal (1898).

- He was a founding member and first president of the American Astronomical Society (1899–1905).

- He was a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (1898).

- He was inducted into the Hall of Fame for Great Americans.

Simon Newcomb's Legacy

Many things are named after Simon Newcomb:

- The asteroid 855 Newcombia is named for him.

- A crater on the Moon called Newcomb is named after him.

- A crater on Mars called Newcomb is also named after him.

- The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada has a writing award in his honor.

- The Time Service Building at the US Naval Observatory is called The Simon Newcomb Laboratory.

- A U.S. Navy ship, the minesweeper Simon Newcomb (YMS 263), was launched in 1942.

- Mt. Newcomb (13,418 ft/4,090 m) in the Sierra Nevada mountains is named after him.

See also

In Spanish: Simon Newcomb para niños

In Spanish: Simon Newcomb para niños

- William Newcomb

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |