St Mary's Church, Bridgwater facts for kids

Quick facts for kids St Mary's Church |

|

|---|---|

St Mary's Church from the southeast (April 2015)

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | Bridgwater, Somerset, England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| History | |

| Status | Parish church |

| Founded | c. 1066 |

| Dedication | Mary, Mother of Jesus |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade I |

| Designated | 24 March 1950 |

| Style | Decorated Gothic, Perpendicular Gothic |

| Years built | c. 1300-1430 |

| Specifications | |

| Spire height | 174 feet (53 m) |

| Bells | 12 + flat sixth |

| Tenor bell weight | 25 long cwt 1 qtr 1 lb (2,829 lb or 1,283 kg) |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Bridgwater St. Mary |

| Benefice | Bridgwater St Mary and Chilton Trinity |

| Deanery | Sedgemoor |

| Archdeaconry | Taunton |

| Diocese | Bath & Wells |

| Province | Canterbury |

St Mary's Church, also known as the Parish Church of St Mary, is the main Church of England church in Bridgwater, Somerset. It was first built a very long time ago, even before the Norman Conquest in 1066. The church you see today is a large and impressive building. Most of it was built in the 1300s and 1400s, but it also has older parts and some newer additions.

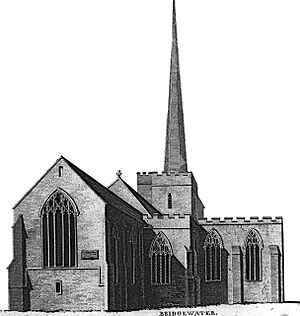

This church is special because of its Gothic architecture, which means it has tall, pointed arches and big windows. It also has a very tall spire, which is like a pointy tower. Most churches in Somerset have tall towers, but not many have spires this high. St Mary's spire is 174 feet (53 meters) tall, making it the tallest medieval spire in the county. An expert named Nikolaus Pevsner called the spire "exceedingly elegant," which means it looks very graceful.

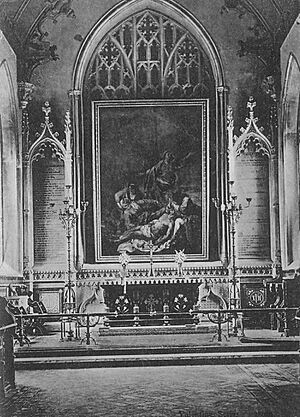

Inside the church, there is a very rare and large painting called the Descent from the Cross. No one knows for sure who painted it, but some people think it was done by famous artists like Bartolomé Esteban Murillo from Spain or Carracci from Italy, both from the 1600s. The church is a major landmark in Bridgwater. Because of its beautiful architecture and special items, it is a Grade I listed building. This is the highest possible rating given by Historic England, showing how important it is. The Church of England also calls it a 'Major Parish Church' because of its size and history.

Contents

History of St Mary's

How the Church Started

Records show there was a church in Bridgwater around 1066, at the time of the Norman Conquest. We don't know exactly where this first church was or much about it. The earliest record of a church on the current spot is from 1107. At that time, the church's money was given to Bath Priory. This was done by the wife of Walter of Douai after he died. Later, Walter's son and even the Pope, Pope Adrian IV, confirmed this gift.

In 1180, Walter's grandson, Fulk Pagnell, who owned the land, gave the church to Marmoutiers Abbey in France. The first vicar, or priest, of the church was recorded a few years later in 1187.

Building the Gothic Church

In 1203, William Brewer became the new owner of Bridgwater. He changed the agreement and gave the church back to Bath Priory. From 1209, William Brewer started rebuilding the church in the Early English Gothic style.

In the early 1300s, the church was made bigger. New sections called aisles were added to the main part of the church (the nave), and a tower was finished at the west end. We don't know the exact dates for these parts, but the tower must have been done by 1318 because a "great" bell was put in it then. In 1367, work began on the tall spire, designed by Nicholas Whaleys. People in the town, through their wills, and even people from nearby villages, helped pay for the spire. To support the heavy spire, large stone supports called buttresses were added to the tower between 1383 and 1385. The spire cost about £137, which would be around £100,000 today.

The end of the 1300s and early 1400s saw a lot more building work. The chancel, the area around the altar, was rebuilt between 1395 and 1420 in the Decorated Gothic style. A special screen called a rood screen was built between 1414 and 1420. The main part of the church, the nave, was rebuilt from 1420 to 1430. Building continued into the mid-1400s, with the lady chapel being rebuilt or changed around 1447-1448.

The Reformation's Impact

THOMAS STRETE became the Vicar of St Mary's in 1528. At that time, the church was Roman Catholic. Just a few years later, King Henry VIII declared himself the head of the new Protestant Church of England. This meant Thomas Strete became the first Protestant Vicar of St Mary's.

Before the Reformation, the church was very colorful and bright, with many altars and special priests. But with the changes, many things were removed. Thomas Strete accepted these changes and remained the Vicar. When King Henry VIII died in 1547, his son Edward VI became king. During Edward's rule, all churches were told to use the Book of Common Prayer. After Edward, his Catholic half-sister Mary became Queen. Thomas Strete was still Vicar when Elizabeth I became Queen in 1558. He stayed as Vicar until he died in 1571.

Later Centuries: 1600s to 1800s

A big event for the church happened during the First English Civil War. In 1645, during the Siege of Bridgwater, the church was damaged. It was caught in a fight between the King's soldiers (Royalists) and the Parliament's soldiers (Roundheads). We don't know exactly how much damage was done.

In 1685, during the Monmouth Rebellion, the Duke of Monmouth climbed the church tower. He wanted to see the King's army gathering before the Battle of Sedgemoor. This was the last battle of the war.

In 1814, lightning struck the spire during a bad thunderstorm, causing a deep crack. It was fixed the next year by a local builder named Thomas Hitchings. To stop it from happening again, a lightning conductor was put on top of the spire.

From 1848 to 1857, the church was restored by William H. Brakespear. This cost a lot of money, between £4,000 and £5,000. During this time, the roofs of the nave and aisles were replaced. Old internal balconies were removed, and new benches were added. The tower and spire were also repaired. A small, round room called a vestry was added in 1854, but it was later taken down. The medieval rood screen was cut in half and moved.

Another restoration happened in 1878, costing £2,000. The old gas lights were removed, and the floor was replaced with new tiles. The stained glass windows were fixed, and the stone parts were cleaned. The church was closed for six months during this work.

The 1900s

In 1902, the small octagonal vestry was taken down. From 1903 to 1954, many new stained glass windows were added to the church. These windows were often memorials to people. Windows were added in 1903, 1909, 1911, 1921, 1924, and 1954.

St George's Chapel

In 1920, a new chapel was created inside the church. It was dedicated to Saint George to remember those who died in the First World War. This chapel has special carvings and panels listing the names of people who died in World War I, World War II, and later wars like the Korean and Falklands wars.

More changes were made to the east end of the church in 1937. The floor tiles were removed, and the floor was lowered. The large east window was blocked to make the painting of the Descent of the Cross stand out more. The tower and spire were also repaired again in the 1990s.

Modern Restoration: 2000s

On June 6, 2016, the church closed for a huge restoration project that cost £1 million. This work lasted 13 months and was the biggest in the church's history. The goal was to make the church more modern for today's use and to fix many changes made in the Victorian times. When the old floor was removed, workers found several old burial chambers, which added to the cost.

A big part of the project was cleaning the large wooden roof in the nave. It was covered in dirt and wax. The oak roof was cleaned using soda blasting, which is a gentle way to remove dirt without harming the wood. This cleaning was finished in September 2016. After that, the walls were repainted.

In the following months, new underfloor heating pipes and electrical systems were installed. Then, 800 large stone tiles were laid across the entire church floor. These new tiles replaced the medieval ones that the Victorians had removed. The stone came from a quarry in Somerton. The church benches were also made smaller, restored, and put on movable frames. This allows the church space to be used more flexibly. A new kitchen was built, and new lighting was installed.

The church reopened in July 2017 and was praised for the work.

Church Leaders

St Mary's has had 51 Vicars since Ralph, the first recorded priest around 1170. Before the Reformation, there were also special priests for different chapels. Many of the Vicars lived in houses across the street from the church, which is now part of the Old Vicarage Restaurant.

Some of the Vicars became well-known, including:

- John Norman (1647-1662)

- Moses Williams (1732-1742)

- Michael Ferrebee Sadler (1857-1864)

- Henry Dixon (1920-1923)

Education and Schools

A church school existed in Bridgwater during medieval times. After the monasteries were closed in 1561, it became the Free Grammar School. Over time, other schools were started.

In the 1800s, there were disagreements between the Church of England and other Christian groups about how children should be educated. This led to two main groups funding new schools:

- The National Society (for Church of England schools)

- The British and Foreign School Society (for other Christian groups)

Between 1824 and 1870, several schools were set up in Bridgwater by these groups. Many churches also had Sunday schools.

Some of the National Schools included:

- An Infants' school (1830), which later joined with the Girls' National School.

- A Boys' school (1839).

- A Girls' school (1830), which became St Mary's Church of England School. It later moved and joined with St Matthew's School.

- The West Street Ragged School (1860), which helped poor children. It later became St Matthew's C. of E. school and moved to a new site.

Church Design

Layout of the Church

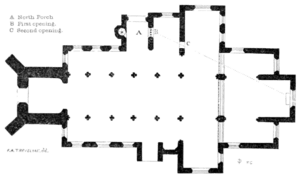

St Mary's Church has a traditional but complex layout, shaped like a cross. It faces east to west. The building includes:

- A sanctuary (the area around the altar)

- A choir area with chapels on the north and south sides

- A main nave (the central part where people sit) with aisles on either side

- Transepts (the arms of the cross shape) with porches

- A low tower at the west end

North of the chancel is a vestry, which is a room for the clergy. The church is very large, covering about 1085 square meters. It is the sixth-largest parish church in Somerset.

Outside the Church

The outside of the church is built from different materials. These include red Wembdon sandstone in the tower and chancel, and blue lias limestone. Bath stone is also used for decoration. The most important part of the outside is the tower and spire, which together are 174 feet tall. This makes it the tallest medieval spire in the county.

The tower is the oldest part of the outside, built in the early 1300s. It has two main sections. The top part has openings for bells. The tower is topped with a simple, castle-like edge. It is 60 feet tall. On the south side of the tower, there is a tall, square staircase tower. Above the tower is the slender spire, which is 114 feet tall and has eight sides. Unlike other famous spires, this one has very little decoration on the outside.

The nave has aisles and a clerestory (a row of windows high up). It is lit by large windows with stone bars called transoms. The north and south transepts have large round windows with star-shaped patterns. The north transept has a late 1800s window with fancy patterns. The chancel is made of red Wembdon sandstone and has a large five-light east window.

Inside the Church

The floor inside the church is made of colorful Victorian tiles and modern blue lias stone, from 1878 and 2017. The chancel has a 1400s ceiling that looks like a barrel, with carved decorations. Every fourth support is richly decorated with angels. The chancel ceiling has 70 carved bosses (decorative carvings) from the late 1300s and early 1400s. These carvings show plants like ferns, Christian symbols like the Star of David, and mythical creatures like unicorns. These bosses were cleaned and restored between 2016 and 2017. The chancel window is blocked by a large altarpiece, which is the rare 17th-century painting.

The nave also has a special roof called a hammerbeam roof, from the 1800s. It rests on carved angel supports. Like the chancel roof, this was cleaned in 2016-2017. The nave has six sections and is separated from the aisles by arches.

The church is unusual because it has balconies in the transepts. The north balcony has wide, rounded arches. The south balcony has one pointed arch. Both balconies have stone railings.

Stained Glass Windows

Most of the church's original stained glass was destroyed during the Reformation and the English Civil War. After the restoration in the 1800s, many clear glass windows were replaced with stained glass.

One of the first new stained glass windows was in the south porch. It was made by Alfred Beer of Exeter. Later, this window was replaced with clear glass again, so we don't know what the stained glass looked like.

In 1852, a much larger window in the Corporation Chapel was also made by Alfred Beer. This window, which is still there today, has the oldest stained glass in the church. It shows symbols of the Crucifixion and the town's coat of arms.

More windows were added in 1876 in St George's Chapel. These were made by the famous London company Clayton and Bell. Three more windows were installed in 1880, and three more by the end of the 1800s. An additional six stained glass windows were put in between 1903 and 1954. This means the church now has 15 stained glass windows in total.

Church Items

The Altarpiece Painting

The most important treasure in the church is its very rare and large altarpiece painting. It is a 17th-century painting showing the Descent from the Cross. The painting was given to the church in 1780 by Lord Anne Poulet. He got it when the ship carrying it stopped in Plymouth. The painting's history and who painted it are still debated.

Some sources say it's a 17th-century French painting, while others say it's by an unknown Italian artist. Some people think it was painted by the Italian artist Annibale Carracci, and others believe it was by Murillo because of the similar style.

The painting shows Jesus at the bottom of the cross, with Saint John bending over him. Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary, who has fainted, are also in the painting. The painting was restored in 1930. It is so large, about 8 feet wide and 13 feet tall, that it blocks the east window.

Woodwork

Rood Screen

The nave originally had a carved medieval rood screen that separated it from the chancel. Later, the organ was placed above it. During the restoration in the 1800s, the medieval rood screen was removed and cut into two pieces. Each half was placed behind the choir stalls, where they are today. Each screen has five symbols, which are the initials of ten unknown people connected to the church.

In the Jacobean period, another screen was added to the west, called the 'Corporation Screen'. In 1849, this screen was turned to divide the rest of the church from the Corporation Chapel, where the town's councillors would sit. Some parts of this screen were later used to support a table in another church nearby. The screen is very decorative, with 17 carved heads and a fancy border at the top.

Credence Table

One of the church's lesser-known treasures is a rare 14th-century desk. It has carvings in the Decorated Gothic style and is shaped like an octagon. It was removed in the 1800s but returned to the church in 1930 and made into a credence table (a small table used in church services). We don't know what its original purpose was.

Burials and Memorials

In the south aisle of the nave, there are two old, unidentified grave slabs from the Early English period. They have a Greek cross carved on them.

Other important memorials include a large marble monument to Sir Francis Kingsmill from 1620-1621. There is also a royal coat of arms from 1712 and a partially damaged Masonic memorial from the 1800s.

Music in the Church

The Organ

Early Organs

The first record of an organ at the church is from 1448. Documents show that the church paid for two "bellows" for the organ. This early organ was probably small, like a modern upright piano, with only one keyboard. This organ seems to have lasted for a long time, as it was repaired in the early 1600s.

A new organ was installed in 1700. It was located in a special loft above the rood screen. It was repaired in 1810 and then moved in 1823 to a new large gallery at the west end of the church.

Organs in the 1800s

During the 19th-century restoration, it was decided to make the organ much bigger and repair it. The organ was rebuilt with new parts and made to sound better. Seven new stops (which change the sound) were added, along with pedals and new bellows. The rebuilt organ was opened in 1849. However, it was exposed to dust during the church building work and broke down in 1852, needing more repairs.

Despite the repairs, the organ soon became unplayable. In 1868, the church decided to get a quote from a famous organ builder, 'Father' Henry Willis. He quoted £550 for a new organ. The new organ was finally installed in 1871.

The Choir

The Victorian restoration aimed to bring back older church traditions. A male choir of 60 men and boys was formed. They sang in the choir stalls, following the style of Cathedrals. Before this, most parish churches didn't have robed choirs. Instead, people sang Metrical Psalms and later hymns.

Organs in the 1900s

The organ was rebuilt in 1922 by Vowles of Bristol, who added modern features. Just 16 years later, Willis & Sons returned to work on the organ again. The organ was repaired and updated three more times before the end of the century.

In 1965, Percy Daniels & Co rebuilt the organ. They tried to keep the original sound but added six more stops. The work was finished in March 1966. Two more overhauls happened in 1975 and 1979. The organ was covered during the 2016-2017 restoration to protect it from dust.

The Bells

Early Bells

We don't know exactly when the tower first had bells. By the mid-1500s, there were five bells. The smallest bell was recast in 1615 and is the oldest surviving bell in the tower. It is also the only bell in the British Isles made by these two founders together. In 1640, a new bell was added, making a total of six. Two more bells were added in 1745, bringing the total to eight.

Bells in the 1800s

The bells stayed mostly the same until 1868, when John Taylor & Co recast the largest bell (the tenor). In 1879, the bells were rehung. However, this wasn't good enough, because 20 years later, in 1899, they needed more restoration. Taylor's company took all eight bells to their factory.

The smallest and fifth bells were recast, and the others were retuned. The bells were rehung with new parts and a new metal frame.

Modern Bells: 2000s

In 1899, bell-hanging companies used plain bearings, which needed regular oiling. By 1979, these were worn out, making the bells hard to ring. So, Taylor's rehung the bells with ball bearings. In 1980, the ringing chamber was moved higher up in the tower.

In 2012, the bells were checked to see if more could be added. A plan was launched in 2015 to add more bells, eventually aiming for a total of twelve. The fundraising goal was £195,000. By 2017, £86,000 had been raised.

Work started in October 2019, thanks to a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund. Two new bells were cast. In December, all the existing bells and their frame were removed from the tower and sent to the factory. Two more new bells were cast in December, and an extra semitone bell was ordered, making 13 bells in total. This 13th bell, called a flat sixth, allows for more combinations of bells to be rung. It was cast in March 2020.

At the factory, the old metal frame was changed and made bigger to hold the five extra bells. The old parts were fixed up and reused, and the new bells got matching parts. The metal frame returned to the church in June 2020, and the bells returned two weeks later. It took a month to install them. The bells were first rung on July 24, but because of coronavirus restrictions, only four ringers were allowed in the tower.

It wasn't until August 17, 2021, that enough restrictions were lifted to allow all twelve bells to be rung for the first time. The bells were officially rededicated at a special service on June 12, 2022. The first full peal (a long ringing performance) on the new set of twelve bells happened on March 4, 2023. It took 3 hours and 22 minutes to complete.

The church now has a set of twelve bells plus an extra semitone bell. These bells were made by different companies over many years, including Taylor bells from 1868, 1899, 2019, and 2020. There are also two bells from 1721, and one each from 1745, 1640, and 1615. The largest bell now weighs about 2,829 pounds (1,283 kg).

See also

- Grade I listed buildings in Sedgemoor

- List of Somerset towers

- List of ecclesiastical parishes in the Diocese of Bath and Wells