2007–2008 financial crisis facts for kids

The 2007–2008 financial crisis, also known as the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), was a very serious worldwide economic crisis. It happened in the early 21st century and was the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression in 1929. Many things led to this crisis, like banks giving risky loans to people with low incomes. Also, big financial companies took too many chances, and a housing bubble burst in the United States. It was like a "perfect storm" of problems.

Investments called mortgage-backed securities (MBS), which were linked to American homes, lost a lot of their value. Other complex financial products called derivatives, which were connected to these MBS, also became almost worthless. Financial companies all over the world were badly hurt. The crisis reached its peak when Lehman Brothers went bankrupt on September 15, 2008. This led to a global banking crisis.

The crisis had many causes. Years before, the U.S. Congress passed laws to help people get loans for affordable housing. But in 1999, parts of the Glass-Steagall law were removed. This allowed banks to mix their safe banking activities with risky trading. A big reason for the financial collapse was the fast growth of risky loan products. These loans targeted low-income homebuyers, often from minority groups, who did not have much information. Regulators did not pay enough attention to this market, so the U.S. government was surprised when the crisis hit.

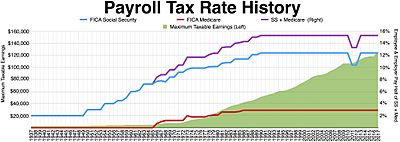

After the crisis began, governments spent huge amounts of money to help financial companies. They used bail-outs and other economic plans to stop the global financial system from completely falling apart. In the U.S., the $800 billion Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 in October did not stop the economy from falling. However, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which was a similar size and included a payroll tax credit, helped the economy start to get better less than a month after it began in February 2009. This economic downturn also set the stage for the European debt crisis.

In 2010, the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was passed in the U.S. to make the financial system more stable. Countries worldwide also adopted new rules called Basel III to make banks safer.

Contents

- What Caused the 2008 Financial Crisis?

- Key Moments of the Financial Crisis

- Why the Housing Bubble Burst

- The IndyMac Bank Failure

- Books and Movies About the Crisis

- Images for kids

- See also

What Caused the 2008 Financial Crisis?

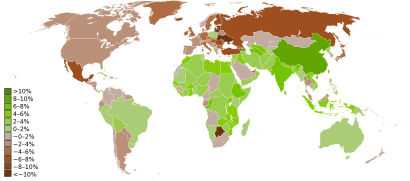

The crisis started the Great Recession. At that time, this was the worst global economic slowdown since the Great Depression. After this, the European debt crisis began in Greece in late 2009. Also, the 2008–2011 Icelandic financial crisis happened, where all three major banks in Iceland failed. Compared to its size, Iceland had the biggest economic collapse of any country in history. The crisis was one of the five worst financial crises ever. It caused the global economy to lose more than $2 trillion.

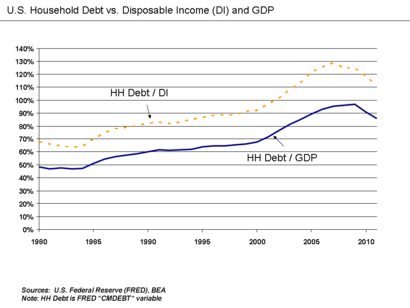

In the U.S., home mortgage debt compared to the total economy (GDP) grew a lot. It went from about 46% in the 1990s to 73% in 2008, reaching $10.5 trillion. As home values went up, many people took out more money from their homes (cash out refinancing). This led to more spending, which could not continue when home prices fell. Many financial companies owned investments based on home mortgages, like mortgage-backed securities. They also owned credit derivatives, which were like insurance for these investments. The value of these investments dropped a lot. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated that large banks in the U.S. and Europe lost over $1 trillion from bad investments and loans between 2007 and 2009.

When investors lost trust in banks and it became harder to get loans, stock and commodity prices fell sharply in late 2008 and early 2009. The crisis quickly spread around the world, causing several bank failures. Economies everywhere slowed down because getting credit became difficult and international trade decreased. Housing markets suffered, and many people lost their jobs. This led to evictions and foreclosures. Many businesses also failed.

From its highest point in mid-2007, the total wealth of households in the United States dropped by $11 trillion by early 2009. This meant people spent less, and businesses invested less. In late 2008, the U.S. economy shrank by 8.4% in just three months. The U.S. unemployment rate reached 11.0% in October 2009. This was the highest rate since 1983 and about twice what it was before the crisis. The average hours worked per week fell to 33, the lowest since records began in 1964.

The economic crisis began in the U.S. but spread globally. U.S. spending was a big part of global economic growth between 2000 and 2007. The rest of the world relied on U.S. consumers to buy their goods. Risky investments were owned by companies and investors worldwide. Financial products like credit default swaps also linked large financial companies together. As financial companies sold assets to pay back debts they could not refinance, the crisis got worse, and international trade decreased. Developing countries grew slower because trade, commodity prices, investment, and money sent home by workers (remittances) all fell. Countries with weak political systems worried that foreign investors would take their money out because of the crisis.

Governments and central banks, like the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, and the Bank of England, provided huge amounts of money. They gave trillions of dollars in bailouts and stimulus packages. This included big spending plans and money policies to stop the economy from collapsing further. They wanted to encourage lending, bring back trust in the commercial paper markets, avoid a deflationary spiral (where prices keep falling), and give banks enough money for customers to withdraw their savings. Central banks became the "lender of only resort" for a large part of the economy. In some cases, the Fed was seen as the "buyer of last resort." In late 2008, these central banks bought $2.5 trillion of government debt and troubled private assets from banks. This was the biggest injection of money into the credit market and the largest money policy action in history.

Following a plan from the 2008 United Kingdom bank rescue package, governments in Europe and the U.S. promised to cover the debt of their banks. They also increased the capital of their banking systems, buying $1.5 trillion in newly issued preferred stock in major banks. The Federal Reserve created a lot of new money to fight the liquidity trap (when interest rates are very low, and people hoard money).

The bailouts involved trillions of dollars in loans, asset purchases, guarantees, and direct spending. There was a lot of debate about these bailouts, like the AIG bonus payments controversy. This led to new ways of making decisions during financial crises. Alistair Darling, who was in charge of the U.K.'s money at the time, said in 2018 that Britain was just hours away from "a breakdown of law and order" on the day the Royal Bank of Scotland was bailed out. Instead of using the stimulus money for more loans at home, some banks invested it in more profitable areas like growing markets and foreign currencies.

China became a more important global player during the crisis. While Western countries faced financial disaster, China provided credit for building new infrastructure. This helped stabilize the global economy and also allowed China to improve its own infrastructure. China's strong performance during the crisis made its leaders more confident that global power was shifting towards China.

In July 2010, the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was passed in the United States. Its goal was to make the U.S. financial system more stable. The Basel III rules for banks were also adopted worldwide. Since the 2008 crisis, consumer regulators in America have watched credit card and home mortgage sellers more closely. This is to stop unfair practices that led to the crisis.

Two major reports about the crisis's causes were made by the U.S. Congress. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission report came out in January 2011. Another report by the United States Senate Homeland Security Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, called Wall Street and the Financial Crisis: Anatomy of a Financial Collapse, was released in April 2011.

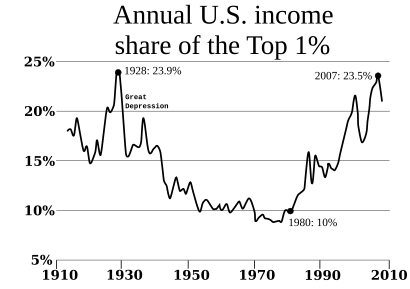

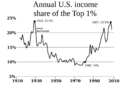

Most American families did not do well. Even wealthy families, but not the very richest, saw their wealth decline. However, half of the poorest families in the United States did not lose wealth during the crisis. This is because they generally did not own financial investments that can change in value. The Federal Reserve surveyed 4,000 households between 2007 and 2009. It found that 63% of all Americans lost wealth. 77% of the richest families saw their wealth decrease, but only 50% of those at the bottom of the wealth pyramid had a decrease.

Key Moments of the Financial Crisis

The following is a list of important events during the financial crisis. It includes how governments responded and when the economy started to recover.

- May 19, 2005: A fund manager named Michael Burry made a special bet against risky home loans. He thought they would become unstable within two years.

- 2006: After many years of rising prices, home prices stopped going up. More people started falling behind on their mortgage payments. This led to the U.S. housing bubble bursting. Because banks were not strict enough, one-third of all mortgages in 2006 were very risky loans.

- May 2006: JPMorgan warned its clients that the housing market would get worse.

- August 2006: A financial sign called the "yield curve" inverted. This usually means an economic slowdown is likely within a year or two.

- November 2006: UBS warned about a coming crisis in the U.S. housing market.

- February 27, 2007: Stock prices in China and the U.S. fell a lot. Reports showed home prices were dropping, and orders for big-ticket items were down. This made people worry about economic growth. Alan Greenspan predicted an economic slowdown. Because more people were not paying their risky loans, Freddie Mac said it would stop investing in some of these loans.

- April 2, 2007: New Century, a company that specialized in risky home loans, filed for bankruptcy. This made the subprime mortgage crisis worse.

- June 20, 2007: Bear Stearns had to help two of its investment funds with $20 billion. These funds had a lot of risky mortgage investments. Bear Stearns said the problem was under control.

- July 19, 2007: The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) stock market index closed above 14,000 for the first time.

- July 31, 2007: Bear Stearns closed its two troubled investment funds.

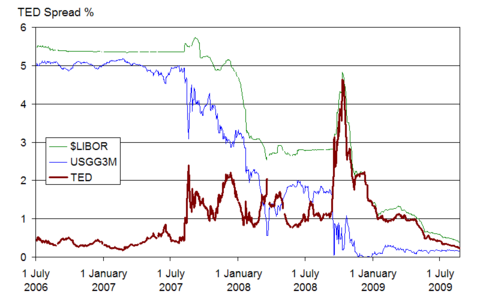

- August 9, 2007: BNP Paribas stopped people from taking money out of three of its investment funds. This was because there was "no liquidity" (no one wanted to buy or sell the investments), making it impossible to value the funds. This was a clear sign that banks were afraid to do business with each other.

- August 16, 2007: The DJIA closed much lower after falling for many days.

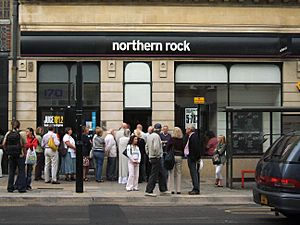

- September 14, 2007: Northern Rock, a British bank, needed help from the Bank of England. This caused panic among investors and a bank run (many people trying to withdraw their money at once).

- September 18, 2007: The Federal Open Market Committee started lowering interest rates. They were worried about money flow and trust in the economy.

- September 28, 2007: NetBank failed and filed for bankruptcy because of its risky home loans.

- October 9, 2007: The DJIA reached its highest closing price ever.

- December 2007: Unemployment in the U.S. reached 5%.

- January 11, 2008: Bank of America agreed to buy Countrywide Financial.

- January 21, 2008: Stock markets in the U.K. fell sharply, the biggest drop since 9/11.

- January 22, 2008: The U.S. Federal Reserve cut interest rates by a large amount to boost the economy.

- March 17, 2008: Bear Stearns was close to bankruptcy. The Federal Reserve stepped in to help JPMorgan Chase buy it for a very low price.

- July 11, 2008: IndyMac bank failed. Oil prices reached their highest point ever.

- September 7, 2008: The U.S. government took over Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two large housing finance companies.

- September 15, 2008: Lehman Brothers went bankrupt. This caused the DJIA to drop by a huge amount, its worst decline in seven years. To avoid bankruptcy, Merrill Lynch was bought by Bank of America.

- September 16, 2008: The Federal Reserve took over American International Group (AIG), a huge insurance company, with $85 billion in funding.

- September 17, 2008: Investors pulled $144 billion from U.S. money market funds. This was like a bank run on these funds. This made it hard for companies to get short-term loans. The U.S. government then insured money market accounts.

- September 18, 2008: Top U.S. officials, including United States Secretary of the Treasury Henry Paulson and Chair of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke, warned Congress that the credit markets were about to completely collapse. Bernanke said, "If we don't do this, we may not have an economy on Monday."

- September 20, 2008: Paulson asked Congress for $700 billion to buy risky mortgages. He said, "If it doesn't pass, then heaven help us all."

- September 21, 2008: Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley changed from investment banks to regular banks. This gave them more protection from the Federal Reserve.

- September 26, 2008: Washington Mutual went bankrupt after people withdrew $16.7 billion in 10 days.

- September 29, 2008: The House of Representatives voted against the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008. This caused the DJIA to drop by a record amount. Stock markets worldwide fell sharply.

- October 3, 2008: The House of Representatives passed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008. President Bush signed it into law.

- October 6–10, 2008: The DJIA fell for five days in a row, losing 18.2% of its value. This was its worst weekly decline ever.

- October 7, 2008: The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) increased deposit insurance to $250,000 per person.

- October 11, 2008: The head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned that the world financial system was "on the brink of systemic meltdown."

- October 14, 2008: The Icelandic stock market reopened after being closed. It fell by about 77% after the value of its three big banks was set to zero.

- October 24, 2008: Many stock exchanges around the world had their worst declines in history. The deputy governor of the Bank of England said, "This is a once in a lifetime crisis, and possibly the largest financial crisis of its kind in human history."

- November 6, 2008: The IMF predicted a worldwide economic slowdown for 2009.

- November 20, 2008: Iceland got an emergency loan from the IMF after its banks failed.

- December 1, 2008: The U.S. officially announced it was in an economic slowdown since December 2007. The Dow fell sharply.

- December 16, 2008: The main interest rate in the U.S. was lowered to zero percent.

- December 20, 2008: Money from the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) was given to General Motors and Chrysler, two large car companies.

- January 20–26, 2009: Protests in Iceland grew, and the Icelandic government collapsed.

- February 13, 2009: Congress approved the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a $787 billion plan to boost the economy. President Barack Obama signed it on February 17.

- February 27, 2009: The DJIA closed at its lowest value since 1997. This happened as the U.S. government increased its ownership in Citigroup, raising fears that banks would be taken over by the government.

- March 6, 2009: The Dow Jones hit its lowest point, a 54% drop from its peak in October 2007. After this, it began to recover.

- March 10, 2009: Shares of Citigroup rose sharply after its CEO said the company was making money. This marked the lowest point of the stock market decline.

- June 2009: The U.S. economic slowdown officially ended.

- July 21, 2010: The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act became law.

- September 12, 2010: European regulators introduced new rules for banks called Basel III. These rules aimed to make banks safer by requiring them to hold more capital.

- November 3, 2010: The Federal Reserve announced another round of "quantitative easing" (QE2). This involved buying $600 billion in government bonds to help the economy grow.

- March 2011: Two years after the crisis's lowest point, many stock markets were 75% higher than their lows.

- July 26, 2012: During the European debt crisis, the head of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, said, "The ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro."

- September 13, 2012: The Federal Reserve announced another round of "quantitative easing" (QE3). This involved buying $40 billion in government bonds each month to lower interest rates and support the housing market.

- 2014: A report showed that the gap between rich and poor families in the U.S. grew wider after the crisis.

- June 2015: A study found that white homeowners recovered faster from the crisis than black homeowners. This made the wealth gap between races in the U.S. even larger.

- 2017: The IMF reported that from 2007 to 2017, richer countries accounted for only 26.5% of global economic growth. Developing countries accounted for 73.5% of global growth.

| Economy |

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (01) |

14,147

|

||||||||

| (02) |

5,348

|

||||||||

| (03) |

4,913

|

||||||||

| (—) |

4,457

|

||||||||

| (04) |

1,632

|

||||||||

| (05) |

1,024

|

||||||||

| (06) |

1,003

|

||||||||

| (07) |

984

|

||||||||

| (08) |

934

|

||||||||

| (09) |

919

|

||||||||

| (10) |

744

|

||||||||

| (11) |

733

|

||||||||

| (12) |

700

|

||||||||

| (13) |

671

|

||||||||

| (14) |

566

|

||||||||

| (15) |

523

|

||||||||

| (16) |

505

|

||||||||

| (17) |

482

|

||||||||

| (18) |

462

|

||||||||

| (19) |

447

|

||||||||

| (20) |

440

|

||||||||

|

The twenty largest economies contributing to global GDP (PPP) growth (2007–2017) |

|||||||||

Why the Housing Bubble Burst

The main reason for the 2007–2008 Financial Crisis was the bursting of the U.S. housing bubble. This led to the subprime mortgage crisis, where many people could not pay back their home loans. Several factors contributed to this:

- Bad Rules and Oversight: A government report found that financial rules and how they were enforced were very weak. The Federal Reserve did not stop the spread of risky investments (Toxic assets).

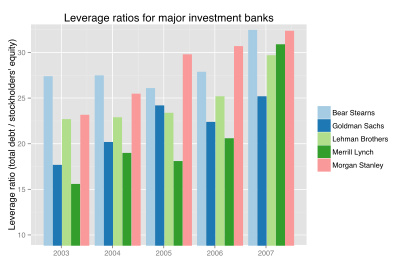

- Risky Behavior by Banks: Many important financial companies took too many risks and borrowed too much money.

- Too Much Borrowing: Both financial companies and regular families borrowed too much. They also made risky investments without being open about them. This set the financial system on a path to crisis.

- Government Mistakes: Government leaders and policymakers were not ready and did not fully understand the financial system. Their inconsistent actions made the panic worse.

- Lack of Responsibility: There was a general breakdown in responsibility and ethics at all levels.

- Poor Lending Standards: Rules for giving out home loans became very loose. The process of turning mortgages into investments (securitization) also failed.

- Unregulated Investments: Complex financial products called derivatives, especially credit default swaps, were not regulated.

- Rating Agency Failures: Companies that rate how risky investments are (credit rating agencies) did not correctly judge the risks.

Another report by the United States Senate said the crisis was caused by "high risk, complex financial products." It also pointed to "hidden conflicts of interest" and the failure of regulators and rating agencies to control Wall Street's excesses.

When many homeowners, especially those with risky loans, stopped paying, the value of mortgage-backed securities and other related investments dropped quickly. As these investments lost value, no one wanted to buy them. Banks that had invested heavily in them started to run out of money.

The process of securitization allowed banks to sell off their loans and the risks that came with them. This meant that mortgage lenders did not have to be as careful about who they lent money to. They could just pass the loans (and their risks) to others.

Rules were too loose, allowing predatory lending in the private sector. This got worse after the government removed state laws against such practices in 2004.

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was a 1977 U.S. law that aimed to help low- and middle-income Americans get home loans. Some argued this law made banks give loans to riskier families. However, studies by Federal Reserve economists found that only a small part of risky loans were related to the CRA. They also found that CRA-related loans performed about the same as other risky loans. These findings suggest the CRA did not play a big role in causing the crisis.

Some argue that government rules encouraged risky lending. This might have caused Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two government-backed companies, to lower their own lending standards to compete.

Mortgage guarantees by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac also played a role. These companies bought many risky loans. The hidden promise by the U.S. government to back these loans encouraged more risky lending.

Other factors included government policies that encouraged home ownership, making it easier for risky borrowers to get loans. Also, bundled risky mortgages were valued too highly, based on the idea that home prices would keep rising. There were also questionable trading practices, and banks paid their employees based on short-term deals rather than long-term value. Banks and insurance companies also did not have enough money to cover their financial promises.

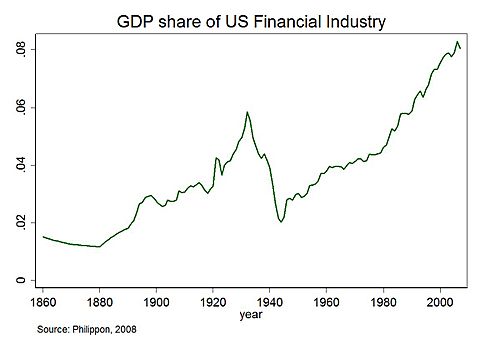

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 removed rules that separated investment banks (which take risks) from regular banks (which hold deposits). This allowed more speculation by regular banks.

Credit rating agencies and investors did not correctly judge the risk of mortgage-related financial products. Governments did not update their rules to match changes in financial markets.

Accounting rules also played a part. In 2006, a rule called SFAS 157 required investments like mortgage securities to be valued at their current market price. When the market for these securities crashed, banks holding them showed huge losses, even if they did not plan to sell them.

Easy access to credit in the U.S., fueled by money from other countries, led to a boom in home building and consumer spending. As banks gave out more loans, home prices rose. Loose lending rules and rising home prices created the housing bubble. Loans of all kinds were easy to get, and people took on a lot of debt.

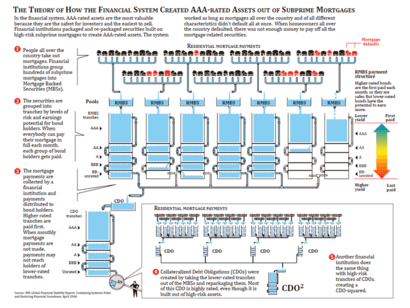

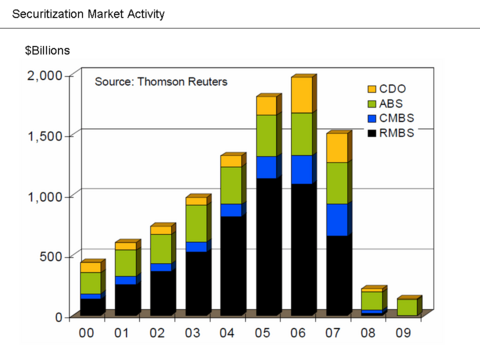

As the housing and credit booms grew, the number of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDO) increased greatly. These products got their value from mortgage payments and home prices. When home prices fell, investors in these products lost a lot of money.

Falling prices also meant that many homes were worth less than the loans on them. This gave homeowners a reason to stop paying and let their homes be taken by the bank. Foreclosures remained high until early 2014. This drained a lot of wealth from consumers. Defaults on other types of loans also increased as the crisis spread. Total losses were estimated to be trillions of U.S. dollars worldwide.

Financial companies like investment banks and hedge funds took on a lot of debt. They did not have enough money to cover large loan defaults or losses. These losses made it hard for financial companies to lend money, slowing down the economy.

Some critics say that government rules forced banks to give loans to people who were not creditworthy. This led to looser lending standards and more mortgage approvals. This, in turn, drove up home prices. Many homeowners then borrowed against the increased value of their homes, leading to too much debt.

Risky Lending Practices (Subprime Lending)

Investment banks and regular banks made it easier to get credit. This led to a big increase in subprime lending, which means giving loans to people with a higher risk of not paying them back. Subprime loans did not become less risky; Wall Street just accepted the higher risk.

Because mortgage lenders competed for customers, they made their lending rules less strict. They gave riskier mortgages to people who were less likely to pay them back. Some experts believe that before 2003, government-backed companies like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac kept lending standards high. But as private companies started to compete more, mortgage standards dropped, and risky loans became common. The riskiest loans were given out between 2004 and 2007.

A different view is that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were the ones who first relaxed lending standards in 1995. They did this by using automated systems to approve loans easily. They also promoted loans with no down payment and worked closely with companies that bundled risky loans.

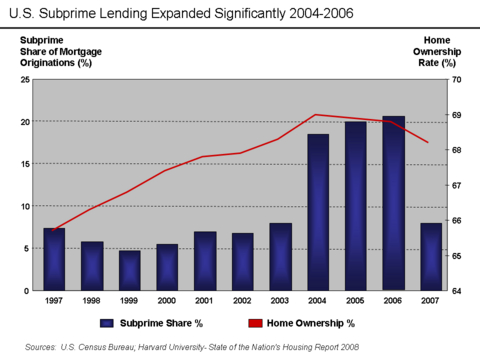

Depending on how "subprime" mortgages are defined, they were less than 10% of all new mortgages until 2004. Then, they rose to nearly 20% and stayed there through 2005–2006, when the U.S. housing bubble was at its peak.

Government Housing Programs

Most reports, including those from the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC) and Federal Reserve economists, say that government policies for affordable housing were not the main cause of the financial crisis. They argue that loans backed by government-sponsored companies performed better than loans from private banks.

However, some, like Peter J. Wallison, believe the crisis came directly from affordable housing policies started by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in the 1990s. They also point to risky loans bought by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Wallison and Edward Pinto estimated that in 2008, Fannie and Freddie held 13 million bad loans worth over $2 trillion.

In the early 2000s, the Bush administration often asked for investigations into the safety of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. They were worried about the growing number of risky loans these companies held. A hearing in 2003 discussed these concerns, but it did not lead to new laws or investigations. Some believe this was an early warning that was ignored.

A 2000 study by the United States Department of the Treasury showed that a lot of mortgage lending went to low- and middle-income areas. Most of these were safe loans. Risky loans from banks covered by the CRA made up a small share in 1998. But leading up to the crisis, 25% of all risky loans came from CRA-covered banks, and another 25% had some connection to CRA. However, most risky loans were not given to the low- and middle-income borrowers targeted by the CRA. The study also found no proof that CRA rules increased loan defaults or caused other lenders to increase risky lending.

Other experts argue that the delay between CRA rule changes in 1995 and the rise of risky lending is normal. They say two things caused the crisis: looser lending rules in 1995 and very low interest rates from the Federal Reserve after 9/11. Both had to be in place for the crisis to happen. Critics also point out that CRA loan promises were huge, totaling $4.5 trillion between 1994 and 2007.

Some have said there were not enough of these risky loans to cause such a big crisis. One trader noted that "There weren't enough Americans with [bad] credit taking out [bad loans] to satisfy investors' appetite for the end product." Investment banks used complex financial products like derivatives to make huge bets, far beyond the actual value of the home loans.

By March 2011, the FDIC had paid out $9 billion to cover losses from bad loans at 165 failed banks. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the bailout for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was over $300 billion.

Economist Paul Krugman argued in 2010 that the simultaneous growth of both home and commercial property bubbles, and the global nature of the crisis, show that U.S. housing policy was not the main cause. He meant that bubbles happened in both markets, but only the home market was affected by these policies.

Countering Krugman, Wallison wrote that not every bubble can cause a financial crisis when it bursts. He noted that other developed countries had big bubbles but much lower losses when they burst. According to Wallison, the U.S. housing bubble led to a financial crisis because it was supported by a huge number of bad loans, often with low or no down payments.

The Housing Bubble's Growth

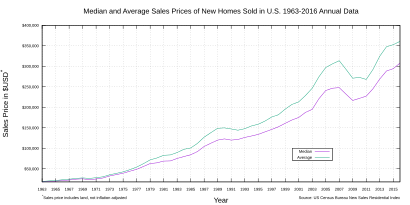

Between 1998 and 2006, the average price of an American house went up by 124%. In the 1980s and 1990s, the national median home price was usually 2.9 to 3.1 times the average household income. But this ratio jumped to 4.0 in 2004 and 4.6 in 2006. This housing bubble meant many homeowners refinanced their homes at lower interest rates. They also borrowed money against the increased value of their homes to spend more.

In a special program, reporters explained that a "Giant Pool of Money" (about $70 trillion in global investments) was looking for higher returns than what U.S. government bonds offered. This pool of money had doubled between 2000 and 2007, but there were not enough safe investments that paid well. Investment banks on Wall Street created products like mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDO). These products were given safe ratings by credit rating agencies.

Wall Street connected this huge pool of money to the U.S. mortgage market. Everyone involved, from mortgage brokers to big investment banks, made huge fees. By about 2003, there were no more safe mortgages to give out. But the strong demand for investments kept pushing banks to lower their lending standards.

CDOs, in particular, allowed financial companies to get money from investors to fund risky loans. This helped the housing bubble grow and generated large fees. CDOs essentially put cash payments from many mortgages into one pool. Then, different investments drew from this pool in a specific order. The investments that were first in line received high ratings. Investments with lower priority had lower ratings but promised higher returns.

By September 2008, average U.S. home prices had fallen by over 20% from their peak in mid-2006. As prices dropped, borrowers with adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs) could not refinance to avoid higher payments. They started to stop paying their loans. In 2007, lenders started foreclosure on nearly 1.3 million homes, a 79% increase from 2006. This number grew to 2.3 million in 2008. By August 2008, about 9% of all U.S. mortgages were either late on payments or in foreclosure. By September 2009, this number rose to 14.4%.

After the bubble burst, economist John Quiggin wrote that this crisis was entirely caused by financial markets. He said there were no other big problems like those that contributed to the Great Depression. Instead, Quiggin blamed the 2008 crisis on financial markets, on political decisions to regulate them too lightly, and on rating agencies that had reasons to give good ratings.

Easy Credit and Debt

Lower interest rates made it easier to borrow money. From 2000 to 2003, the Federal Reserve lowered its main interest rate from 6.5% to 1.0%. This was done to lessen the impact of the dot-com bubble bursting and the September 11 attacks. It also aimed to fight a possible risk of falling prices. By 2002, it was clear that credit was boosting housing, not business investment. Some economists even suggested the Fed needed to create a housing bubble to replace the tech bubble. Studies from developed countries show that too much credit growth greatly contributed to the crisis's severity.

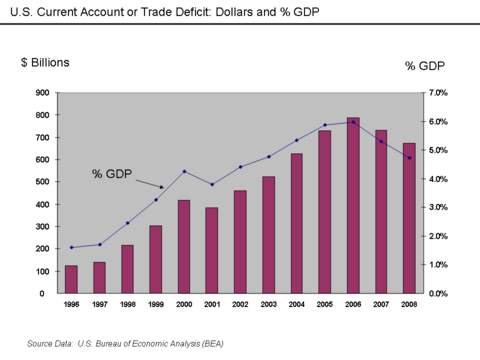

Rising U.S. trade deficits also pushed interest rates down. These deficits peaked with the housing bubble in 2006. Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke explained that trade deficits meant the U.S. had to borrow money from other countries. This process drove up bond prices and lowered interest rates.

Bernanke explained that between 1996 and 2004, the U.S. trade deficit grew by $650 billion. To pay for these deficits, the U.S. had to borrow large amounts from abroad, mostly from countries with trade surpluses. These were mainly growing economies in Asia and oil-exporting nations. This meant large amounts of foreign money flowed into the U.S. to pay for its imports.

All this money created demand for various financial assets, raising their prices and lowering interest rates. Foreign investors had this money to lend because they had very high savings rates (like 40% in China) or because of high oil prices. Ben Bernanke called this a "saving glut."

A flood of money (capital or liquidity) reached the U.S. financial markets. Foreign governments bought U.S. government bonds, which helped them avoid much of the crisis's direct impact. U.S. households used money borrowed from foreigners to spend or to drive up the prices of homes and financial assets. Financial companies invested foreign money in mortgage-backed securities.

The Fed then raised interest rates significantly between July 2004 and July 2006. This made payments on adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs) more expensive for homeowners. This might have also helped burst the housing bubble, as asset prices usually move opposite to interest rates. It became riskier to speculate in housing. U.S. housing and financial assets lost a lot of value after the housing bubble burst.

Weak Lending and Fraud

Lending standards for risky loans became very loose in the U.S. In the early 2000s, a risky borrower had a FICO score of 660 or less. By 2005, many lenders lowered the required FICO score to 620. This made it much easier to get loans, making risky lending even riskier. Lenders stopped checking proof of income and assets as much. Loans went from needing full paperwork to low paperwork, then no paperwork at all. One risky mortgage product was called a NINJA loan (No Income, No Job, No Asset verification). These loans were informally called "liar loans" because they encouraged borrowers to be dishonest.

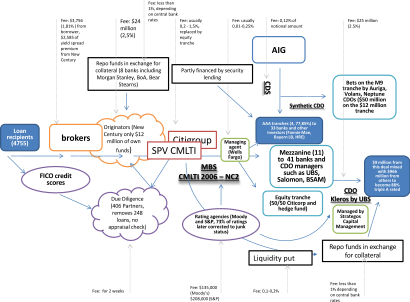

A former chief underwriter for Citigroup testified that by 2006 and 2007, bad mortgage lending was widespread. He said that 60% of mortgages bought by Citigroup from other companies were "defective." This meant they did not follow rules or lacked required documents. By 2007, this number grew to over 80%.

Another company, Clayton Holdings, which checks loans, testified that their review of over 900,000 mortgages from 2006 to 2007 showed that only 54% met the lenders' own rules. Their analysis also showed that 28% of the loans did not meet the basic standards of any lender. Even worse, 39% of these very bad loans were then bundled and sold to investors.

Predatory Lending Practices

Predatory lending is when dishonest lenders trick borrowers into getting "unsafe" or "unwise" loans for wrong reasons.

In June 2008, Countrywide Financial was sued for "unfair business practices" and "false advertising." The lawsuit claimed Countrywide used "deceptive tactics to push homeowners into complicated, risky, and expensive loans." This was so the company could sell as many loans as possible to other investors. In May 2009, Bank of America changed 64,000 Countrywide loans as a result. When home prices dropped, homeowners with adjustable-rate mortgages had little reason to pay their monthly payments, as their home value had disappeared. This caused Countrywide's financial health to worsen, leading to its takeover by regulators. One former Countrywide employee said, "If you had a pulse, we gave you a loan."

Former employees from Ameriquest, a leading lender, said they were pressured to fake mortgage documents. Then, they would sell these mortgages to Wall Street banks eager for quick profits. There is growing evidence that such mortgage fraud may have caused the crisis.

Lack of Rules and Oversight

Many experts believe the financial crisis was caused by a lack of rules in financial markets. A 2012 study suggested that bank rules based on the Basel agreements encouraged risky business practices and made the crisis worse. In other cases, laws were changed, or enforcement became weaker. Key examples include:

- 1980s Deregulation: Laws in the 1980s removed many restrictions on banks. This allowed them to lend more and raised the amount of money insured by the government. This might have made depositors less careful about how banks managed risk.

- 1999 Law Change: In 1999, the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act removed parts of the Glass-Steagall Act. This law had kept investment banks separate from regular banks. This change allowed banks to take more risks. Some say this directly made the crisis worse, while others say it had little impact on the main companies that failed.

- 2004 SEC Rule Change: In 2004, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) relaxed a rule that allowed investment banks to take on much more debt. This fueled the growth of mortgage-backed securities. The SEC admitted that allowing investment banks to regulate themselves contributed to the crisis.

- Shadow Banking: Financial companies in the "shadow banking system" were not regulated like regular banks. This allowed them to take on more debt compared to their financial cushion. This happened even after a similar problem in 1998 with Long-Term Capital Management, which failed and needed a bailout.

- Hidden Debts: Regulators allowed banks like Citigroup to move large amounts of assets and debts off their main balance sheets. They used complex legal structures called structured investment vehicles. This hid how weak the banks' financial position was or how much risk they were taking. This made people more uncertain about the major banks' financial health during the crisis.

- Unregulated Derivatives: As early as 1997, Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan fought to keep the derivatives market unregulated. In 2000, Congress passed a law that banned further regulation of this market. Derivatives like credit default swaps (CDS) can be used to bet on or protect against specific credit risks without owning the actual debt. The amount of CDS outstanding grew 100 times from 1998 to 2008. Warren Buffett famously called derivatives "financial weapons of mass destruction" in 2003.

A 2011 paper suggested that Canada avoided a banking crisis in 2008 because it had one strong regulator. In contrast, the United States had a weak and divided banking system with many competing regulators.

Complex Financial Products

"Financial innovation" means creating new financial products to meet specific goals, like reducing risk or getting loans. In this crisis, examples included: adjustable-rate mortgages; bundling risky mortgages into mortgage-backed securities (MBS) or collateralized debt obligations (CDO) to sell to investors; and credit default swaps (CDS), a type of credit insurance. The use of these products grew hugely before the crisis. These products varied in how complex they were and how easy it was to figure out their value.

CDO sales grew from $20 billion in early 2004 to over $180 billion by early 2007. Then, they dropped back down. Also, the quality of CDOs got worse from 2000 to 2007. The amount of risky and other non-prime mortgage debt in CDOs increased from 5% to 36%. As explained before, CDS and bundles of CDS called synthetic CDOs allowed for huge bets to be made on the value of home loans.

This boom in new financial products also meant more complexity. It increased the number of people and companies involved in a single mortgage. These included mortgage brokers, lenders, companies that bundled loans, traders, investors, and insurers. As they got further from the actual home loan, these groups relied more on indirect information. This included credit scores, property appraisals, and computer models from rating agencies. Instead of spreading risk, this created opportunities for fraud, bad judgments, and eventually a market collapse.

Martin Wolf, a financial writer, said in 2009 that some financial innovations allowed companies to get around rules. For example, "off-balance sheet financing" affected how much debt banks reported. He said that a huge part of what banks did was to find ways around regulations.

Misjudging Risk

Almost everyone involved, from lenders to investors, underestimated mortgage risks. They did not think home prices would fall, based on trends from the past 50 years. Problems with models that predicted defaults and prepayments led to overvaluing mortgages and related products. This happened with lenders, companies that bundled loans, traders, rating agencies, insurers, and most investors. While financial products helped share risk, it was the underestimation of falling home prices and the resulting losses that caused the overall risk.

For many reasons, people in the market did not accurately measure the risk of new financial products like MBS and CDOs. They also did not understand their effect on the financial system's stability. The way CDOs were priced clearly did not show how much risk they brought into the system. Banks estimated that $450 billion of CDOs were sold between late 2005 and mid-2007. Of those that were sold off, the average recovery for "high quality" CDOs was only about 32 cents on the dollar. For riskier CDOs, it was about five cents for every dollar.

AIG insured the debts of various financial companies using credit default swaps. AIG received money in exchange for promising to pay if another party failed to pay its debt. However, AIG did not have enough money to cover its many CDS promises as the crisis worsened. The government took over AIG in September 2008. U.S. taxpayers provided over $180 billion in government loans and investments to AIG. This money then flowed to other financial companies that had CDS agreements with AIG.

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC) conducted the main government study of the crisis.

The limits of a widely used financial model were also not understood. This formula assumed that the price of CDS was linked to and could predict the correct price of mortgage-backed securities. Because it was easy to use, a huge number of CDO and CDS investors, issuers, and rating agencies quickly started using it.

As financial investments became more complex and harder to value, investors felt safe because international bond rating agencies and bank regulators accepted complex math models. These models showed the risks were much smaller than they actually were. George Soros said that the "super-boom got out of hand when the new products became so complicated that the authorities could no longer calculate the risks and started relying on the risk management methods of the banks themselves." He called this a "shocking giving up of responsibility."

A conflict of interest between investment managers and large investors, along with too much investment money globally, led to bad investments in overpriced credit assets. Investment managers are usually paid based on the amount of money they manage for clients. So, they have a reason to manage more money to get paid more. As too much global investment money caused returns on credit assets to fall, managers had a choice. They could invest in assets where returns did not match the true risk, or they could return money to clients. Many managers kept investing client funds in overpriced investments, which hurt their clients. They could claim they did not know the risks because early risky loans had very few losses.

Despite the popularity of the formula, there were efforts in the financial industry before the crisis to fix its problems. These included the lack of how things depended on each other and how it poorly showed extreme events.

Shadow Banking System

There is strong evidence that the riskiest mortgages were funded through the "shadow banking system." Competition from this system may have pushed traditional banks to lower their lending standards and give out riskier loans.

In a 2008 speech, Timothy Geithner, who later became United States Secretary of the Treasury, blamed the freezing of credit markets on a "run" on companies in the "parallel" banking system, also called the shadow banking system. These companies became very important to the financial system's credit markets but were not regulated in the same way. Also, these companies were vulnerable because they borrowed short-term money to buy long-term, hard-to-sell, and risky assets. This meant that problems in credit markets would force them to quickly sell their long-term assets at low prices.

Economist Paul Krugman said the run on the shadow banking system was the "core of what happened" to cause the crisis. He called the lack of rules "malign neglect" and argued that all banking-like activities should have been regulated. Without the ability to get money from investors for most types of mortgage-backed securities or asset-backed commercial paper, investment banks and other companies in the shadow banking system could not provide money to mortgage firms and other businesses.

This meant that almost one-third of the U.S. lending system was frozen. According to the Brookings Institution, the traditional banking system did not have enough money to fill this gap. They said it would take years of strong profits to generate enough capital for that much additional lending. They also suggested that some types of securitization would "likely vanish forever" because they were a result of overly loose credit conditions. While traditional banks made their lending standards stricter, the collapse of the shadow banking system was the main reason for the reduction in available funds for borrowing.

The securitization markets, which the shadow banking system supported, started to close down in early 2007 and almost completely shut down in late 2008. More than a third of the private credit markets became unavailable for funding.

Commodity Prices

In a 2008 paper, economists argued that the financial crisis was partly due to a "global asset scarcity." This led to large amounts of money flowing into the United States and creating asset bubbles that eventually burst. They also suggested that the sharp rise in oil prices after the crisis was a reaction to the financial crisis itself, as people tried to rebuild assets.

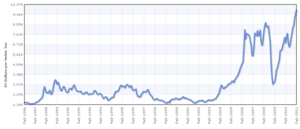

Investments in commodity index funds became popular. One estimate said investments grew from $90 billion in 2006 to $200 billion by the end of 2007, while commodity prices rose 71%. This raised concerns about whether these funds caused the commodity bubble.

Economists Who Predicted the Crisis

Most economists, especially those who follow mainstream economics, largely failed to predict the crisis. A business journal from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania looked into why economists failed. It concluded that they used math models that did not account for the important roles banks and other financial companies play in the economy.

However, several economists who follow different economic ideas did predict the crisis. Dirk Bezemer named 12 economists who saw the crisis coming.

Robert Shiller, who helped create an index that measures home prices, wrote an article a year before Lehman Brothers collapsed. He predicted that a slowing U.S. housing market would cause the housing bubble to burst, leading to financial collapse. Peter Schiff often appeared on TV in the years before the crisis and warned about the coming real estate collapse.

The former Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, Raghuram Rajan, predicted the crisis in 2005. At a celebration for Alan Greenspan, who was retiring as chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, Rajan gave a paper that criticized the financial sector. In it, he argued that "disaster might loom." Rajan said that financial managers were encouraged to "take risks that generate severe adverse consequences with small probability but, in return, offer generous compensation the rest of the time."

Stock trader and financial risk expert Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of the 2007 book The Black Swan, spent years warning about the banking system failing. He said this was because they used bad risk models and relied on forecasting. He even made a large financial bet against banking stocks and made a fortune from the crisis.

Popular articles in the news have made the public believe that most economists failed to predict the financial crisis. For example, The New York Times noted that economist Nouriel Roubini warned of such a crisis as early as September 2006. The New York Times called him "Dr. Doom."

A 2012 article in a journal looked at potential causes of the 2008 crisis in 107 countries. The authors examined many economic signs but found it hard to link most commonly cited causes to the crisis across countries. They were doubtful about "early warning" systems that claim to predict crises.

The Austrian School of economics saw the crisis as a clear example of a predictable bubble caused by too much credit and loose money supply.

The IndyMac Bank Failure

The first major U.S. financial company to get into trouble was IndyMac, based in Southern California. It was a spin-off of Countrywide Financial. Before it failed, IndyMac Bank was the largest savings and loan in Los Angeles and the seventh largest mortgage lender in the U.S. IndyMac Bank's failure on July 11, 2008, was the fourth largest bank failure in U.S. history at that time.

IndyMac Bank was started in 1985. Its main business was giving out and bundling Alt-A loans, which were riskier than traditional loans. This strategy led to fast growth and a high concentration of risky assets. IndyMac grew to be a very large lender. In 2006, it gave out over $90 billion in mortgages.

IndyMac's aggressive growth, use of risky loan products, weak loan checks, and focus on residential real estate in California and Florida (where the housing bubble was biggest) led to its downfall. It also relied heavily on expensive borrowed money.

IndyMac often gave loans without checking the borrower's income or assets, and to people with bad credit histories. The appraisals of the homes were also often questionable. As an Alt-A lender, IndyMac's goal was to offer loans that fit borrowers' needs. They used many risky options, like adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs) and loans with no down payment. Ultimately, loans were given to many borrowers who simply could not afford their payments. The bank only stayed profitable as long as it could sell those loans to other investors. IndyMac resisted efforts to regulate its involvement in these loans or make its lending rules stricter.

On May 12, 2008, IndyMac revealed that it might not have enough capital (its own money) in the future. It reported that credit rating agencies had lowered the ratings on many of its mortgage-backed bonds. IndyMac warned that if regulators found its capital position had fallen below "well capitalized," it might not be able to use certain types of deposits.

Senator Charles Schumer later pointed out that these "brokered deposits" made up over 37% of IndyMac's total deposits. He asked the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) if it had considered telling IndyMac to rely less on these deposits.

IndyMac was taking new steps to save money, like delaying interest payments on some investments. Dividends to regular shareholders had already been stopped. The company still had not found a significant new source of money or a buyer. IndyMac reported that its capital was only slightly above the minimum required. But it did not reveal that some of the capital it claimed was made up.

When home prices fell in late 2007 and the market for selling mortgages collapsed, IndyMac was forced to hold $10.7 billion in loans it could not sell. Its money problems got worse in late June 2008 when account holders withdrew $1.55 billion, or about 7.5% of IndyMac's deposits. This bank run followed a public letter from Senator Charles Schumer expressing concerns about IndyMac. While the run contributed to IndyMac's failure, the main cause was how unsafely it was run.

On July 11, 2008, citing money concerns, the FDIC took over IndyMac Bank. A new bank, IndyMac Federal Bank, FSB, was created to take control of IndyMac Bank's assets and insured deposits. The FDIC guaranteed all insured accounts up to $100,000. It also promised to pay 50% of any amounts over $100,000 to about 10,000 depositors. Even with a planned sale, an estimated 10,000 uninsured depositors still lost over $270 million.

With $32 billion in assets, IndyMac Bank was one of the largest bank failures in American history. IndyMac Bancorp filed for bankruptcy on July 31, 2008.

Initially, the companies affected were those directly involved in home building and mortgage lending, like Northern Rock and Countrywide Financial. They could no longer get money through the credit markets. Over 100 mortgage lenders went bankrupt in 2007 and 2008. Worries that investment bank Bear Stearns would collapse in March 2008 led to its quick sale to JP Morgan Chase. The financial crisis reached its peak in September and October 2008. Several major companies either failed, were bought under pressure, or were taken over by the government. These included Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Washington Mutual, Wachovia, Citigroup, and AIG. On October 6, 2008, three weeks after Lehman Brothers filed the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history, Lehman's former CEO Richard S. Fuld Jr. appeared before Congress. Fuld said he was a victim of the collapse, blaming a "crisis of confidence" in the markets for his firm's downfall.

Books and Movies About the Crisis

- Crash Proof: How to Profit From the Coming Economic Collapse by Peter Schiff (2007). This book described what led to the U.S. housing bubble and warned of the coming decline.

- Meltdown: A Free-Market Look at Why the Stock Market Collapsed, the Economy Tanked, and the Government Bailout Will Make Things Worse by Tom Woods (2009).

- Inside Job (2010). This documentary film about the crisis won an Academy Award.

- The Big Short by Michael Lewis. This best-selling book was made into a film in 2015. It won an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. The story shows how some people outside the main financial world saw the crisis coming.

- Margin Call (2011). This movie is set the night before the crisis broke. It follows traders trying to stop the damage after an analyst finds information that could ruin their company and possibly the whole economy.

- Too Big to Fail (2011). This film is based on a book about how Wall Street and Washington tried to save the financial system.

- The U.S. documentary program Frontline made several episodes about the crisis:

- "Inside the Meltdown"

- "Ten Trillion and Counting"

- "Breaking the Bank"

- "The Warning"

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Crisis financiera de 2007-2008 para niños

In Spanish: Crisis financiera de 2007-2008 para niños

- Banking (Special Provisions) Act 2008 (United Kingdom)

- List of bank failures in the United States (2008–present)

- 2008–2009 Keynesian resurgence

- 2010 United States foreclosure crisis

- 2012 May Day protests

- 2000s commodities boom

- Crisis theory

- Kondratiev wave

- List of banks acquired or bankrupted during the Great Recession

- List of banks acquired or bankrupted in the United States during the 2007–2008 financial crisis

- List of acronyms associated with the eurozone crisis

- List of economic crises

- List of entities involved in 2007–2008 financial crises

- List of largest bank failures in the United States

- Low-Income Countries Under Stress

- Mark-to-market accounting

- Neoliberalism

- Occupy movement

- PIGS (economics)

- Private equity in the 2000s

- Subprime crisis impact timeline

- The Chicago Plan Revisited

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |