- This page was last modified on 17 October 2025, at 10:18. Suggest an edit.

A&P facts for kids

A&P logo, 2006–2009

|

|

A&P's final headquarters, now demolished and replaced with an upscale townhome development, in Montvale, New Jersey

|

|

|

Trade name

|

A&P |

|---|---|

|

Formerly

|

Gilman & Company (1859–1869) |

| Public | |

| Industry | Grocery |

| Fate | Chapter 11 bankruptcy Liquidation |

| Founded | February 17, 1859 in New York City, New York, United States |

| Founders | George Gilman George Huntington Hartford |

| Defunct | November 2015; 8 years ago |

| Headquarters |

,

US

|

|

Number of locations

|

15000 at peak (1930) 296 at liquidation (2015) |

|

Areas served

|

United States |

|

Number of employees

|

28,500 (2015) |

The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, usually called A&P, was a big American chain of grocery stores. It operated for a very long time, from 1859 to 2015. For many years, from 1915 to 1975, A&P was the largest grocery seller in the United States. Until 1965, it was even the largest U.S. retailer of any kind!

A&P was a famous American company. The Wall Street Journal said it was once as well known as McDonald's or Google are today. In the 1940s, A&P handled 10% of all grocery spending in the U.S. The company was known for new ideas. It helped people eat healthier by offering many different foods at much lower prices. Until 1982, A&P also made a lot of its own food products.

A&P started in 1859 as "Gilman & Company." It was founded by George Gilman in New York City. He opened a few small stores that sold tea and coffee. Then, he expanded it into a national mail order business. By 1878, the company had 70 stores. By 1900, it had almost 200 stores. A&P grew a lot by introducing "economy stores" in 1912. By 1915, it had 1,600 stores. After World War I, A&P added stores that sold meat and fresh produce. It also expanded its food manufacturing.

In 1930, A&P was the world's largest retailer. It made $2.9 billion in sales and had 15,000 stores. In 1936, it started using the self-serve supermarket idea. By 1950, it had opened 4,000 larger stores, closing many smaller ones. After facing financial troubles twice, A&P finally closed its last stores in 2015.

Contents

A&P's Journey: From Tea to Supermarkets

Early Years (1859–1878): The Gilman Era

The company that became A&P was started in the 1850s. George Gilman (1826–1901) founded "Gilman & Company." In 1859, he began selling tea and coffee from a store in Manhattan. In 1863, the company became a retailer called "Great American Tea Company." It quickly opened five stores.

Gilman was very good at advertising. His business grew fast by offering low prices. The company could do this because it was both the seller and the supplier. Gilman also built a national mail order business. By 1866, the company was worth over $1 million. In 1869, the transcontinental railroad was finished. Gilman then created a new company, the "Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company." This new company sold prepackaged tea called Thea-Nector. Some say George Huntington Hartford helped start this tea company. In 1871, A&P started giving out gifts, like pictures or dishes, when customers bought coffee or tea. These gifts are now collector's items!

The Hartford Era (1878–1951): Growing into a Giant

How Grocery Stores Changed with A&P

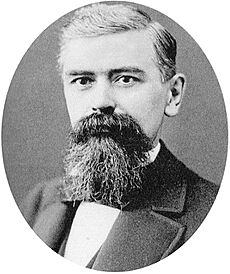

George Huntington Hartford, mid-1870s

George Huntington Hartford joined Gilman & Company as a clerk. He later became a bookkeeper and then a cashier. By 1871, Hartford was in charge of expanding A&P. He helped open A&P's first store outside New York City in Chicago, right after the Great Chicago Fire. The company grew quickly. By 1875, A&P had stores in 16 cities. In 1878, Gilman let Hartford take over running the company. By then, A&P had 70 fancy stores and a mail order business. They made $1 million in sales each year.

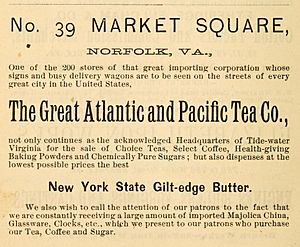

A 1888 advertisement for A&P from a Norfolk, Virginia, guidebook, listing the range of items carried

To make more money, the government raised taxes on tea and coffee. This made profits on these items go down. So, around 1880, A&P started selling sugar. The company kept growing fast. By 1884, it had stores as far west as Kansas City, Missouri and as far south as Atlanta. They also used wagons to deliver to customers in the countryside. Around this time, two of Hartford's sons, George Jr. and John, joined the company. It's said that George Jr. convinced his father to sell more products, like A&P-branded baking powder. Over the next ten years, A&P added other branded products, like condensed milk and spices. As it sold more items, the tea company slowly became the first true grocery chain. By 1900, the company had sales of $5 million from 198 stores.

In 1901, George Gilman died without a will, leading to a legal fight among his family. Hartford stepped in, saying Gilman had given him half the company in 1878. Evidence showed Hartford had received half of A&P's profits since 1878. The family realized the company would struggle without Hartford. So, in 1902, they agreed to make A&P an official company. Hartford gained control of the company's voting stock. Over time, Hartford bought back the shares from Gilman's family. A&P opened a new store about every three weeks. A large nine-story building was built in Jersey City, New Jersey, for headquarters and a warehouse. It later added a factory and bakery.

By 1908, George Hartford Sr. divided management among his sons. George Jr. handled money, and John managed sales and operations. The sons ran A&P for over 40 years. John Hartford worked hard to promote the A&P brand, adding many more products. To make room for new items, A&P stopped giving out gifts in stores. Instead, they used Plaid Stamps, like other popular rewards programs. By 1912, A&P had 400 stores. Its delivery wagons also served 5,000 country routes.

The Rise of Economy Stores

Food prices were a big topic in the 1912 presidential election, as they had gone up 35% in 10 years. To help with this, some store chains tried a simple, "no-frills" style. After much discussion, the Hartfords agreed to John's idea of trying an economy store. This store was designed to sell things at a very low profit margin. It cost only $3,000 to start, including its first products. The store had only a manager and no fancy decorations. In just two months, sales went up to $800 a week. A&P quickly opened more of these stores. By 1915, the chain had 1,600 stores.

A&P's huge growth caused problems with suppliers. Cream of Wheat, a big breakfast food maker, wanted all stores to sell its cereal at a set price. A&P bought it for 11 cents a box and wanted to sell it for 12 cents. Cream of Wheat stopped selling to A&P, so A&P sued. A judge ruled against A&P, saying a maker could set retail prices. Because of this, A&P and other big chains started making more of their own store brands.

Hartford Sr. died in 1917. Control of the company went to a trust managed by his sons George, Edward, and John.

Adding More Products: Meat, Produce, and Dairy

After World War I, A&P grew very fast. In 1925, it had 13,961 stores. The newer "combination stores" sold meat, produce, and dairy, along with regular groceries. Sales reached $400 million, and profit was $10 million. However, the Hartford brothers worried that costs were too high. In 1926, they started a plan to lower prices and control costs better. That year, sales increased by 32%. A&P moved its main office to the new Graybar Building in New York City.

In 1927, A&P started a Canadian division. By 1929, it had 200 stores in Ontario and Quebec. In 1930, the company's 16,000 stores made $2.9 billion in sales. This meant A&P had 25% of the grocery market in its areas and about 10% nationwide. No other retail company had ever achieved such results. A&P was twice as big as the next largest retailer, Sears. Unlike most rivals, A&P was in a great position to handle the Great Depression. The Hartfords built their chain without borrowing money. Their low-price model led to even higher sales. From 1929 to 1932, A&P made a record $110 million in profits.

A&P's success also caused some problems. Thousands of small, local grocery stores couldn't compete with A&P's low prices. While small stores didn't have much political power, their suppliers did. Movements against chain stores grew stronger during the Depression. In 1935, a Texas Congressman named Wright Patman suggested a federal tax on chain stores. If this law passed, it likely would have ended A&P.

This law didn't pass, but in 1936, Patman supported the Robinson–Patman Act. This law made it illegal to charge different prices to similar customers. Patman then tried to pass his first bill again. A&P hired a lobbyist and stopped opposing unions. George and John Hartford also wrote an open letter to the public. They explained that the new law would make food prices go up. Public opinion then turned against the bill, and it was defeated.

Switching to Supermarkets

An A&P supermarket, in Snowdon, Quebec, 1941

In 1930, the first supermarket opened in California. On the East Coast, a former A&P employee named Michael J. Cullen opened his first King Kullen supermarket. Two years later, Big Bear opened and quickly made as much money as 100 A&P stores. In 1933, A&P's sales dropped 19% because of this new competition. After much discussion, the Hartford brothers decided to open 100 supermarkets. The first one was in Braddock, Pennsylvania. These new stores were very successful. By 1938, the company had 1,100 supermarkets. A&P continued to build supermarkets and slowly close smaller stores. By 1950, A&P had 4,000 supermarkets and 500 smaller stores. Sales reached $3.2 billion, with a profit of $32 million.

A&P's success caught the eye of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's anti-trust chief, Thurman Arnold. He was asked by Congressman Wright Patman to investigate A&P. In 1942, A&P and its top leaders, including the Hartford brothers, were accused of trying to unfairly control trade. In 1944, the case was dropped.

However, new charges were filed in Danville, Illinois. The government said A&P had an unfair advantage because it owned its own manufacturing, warehouses, and stores. This allowed them to charge lower prices. Prosecutors also said A&P refused to buy from food sellers who didn't give A&P advertising deals. The judges thought that if A&P continued unchecked, it could become a monopoly. A&P argued its grocery market share was only about 15%, much less than leaders in other industries. The judge sided with the government, fining each person $10,000.

In 1949, a higher court supported the decision. A&P decided not to appeal further. In September, the government asked the court to force A&P to separate its manufacturing and break up its retail stores into seven different companies. Thousands of letters supporting A&P poured into the Justice Department. The Hartford brothers gave many interviews and appeared on the cover of Time magazine in 1950. Time wrote that A&P sold more goods than almost any other retailer in the world. John Hartford said, "I don't know any grocer who wants to stay small... I don't see how any businessman can limit his growth and stay healthy." The case continued into the next presidential administration. In late 1953, the government agreed to drop its demands if A&P closed its produce brokerage that also supplied competitors.

In fighting these lawsuits, A&P also highlighted how much they helped the public. The ideas started by the Hartfords helped people eat healthier food at lower costs. In 1950, Americans ate 10% more food than in 1930. Poorer families especially saw a big improvement in the quality of their food.

A&P's decline began in the early 1950s. They didn't keep up with rivals who opened bigger, more modern supermarkets. By the 1970s, A&P stores felt old. Efforts to cut costs led to poor customer service. When these efforts didn't help, the Hartford family and their foundation, who owned most of the company, sold it to the Tengelmann Group from Germany.

Later Years (1951–2015): Challenges and Changes

After the Hartford Family (1951–1974)

A&P's new stores from 1955 to 1970 tended to be smaller than competitors. This unit, in Pluckemin, New Jersey, remained unchanged (except for A&P's "sunrise" logo) until it closed in 2013.

In 1951, John Hartford died. George Hartford remained as chairman, and Ralph Burger became the new president. Burger had started as a clerk in 1910. He was a good manager but didn't have John Hartford's big-picture marketing skills. Under Burger, A&P continued to have record sales.

Burger also led the John A. Hartford Foundation. This meant he controlled A&P when George died in 1957. A&P's stock then started selling on the New York Stock Exchange. For the first time, A&P added outside directors to its board. In late 1961, A&P stock reached its highest price.

The reasons for A&P's decline over the next 35 years began in the 1950s:

- Not enough money for new stores. Most of A&P's profits went to the Hartford family's trust. A&P also didn't like to borrow money. This meant they didn't have enough funds to build bigger, modern supermarkets like their rivals. By 1970, A&P stores were much smaller and older than other chains.

- Too much focus on store brands. In 1951, the Supreme Court ruled that manufacturers couldn't set minimum prices. This led to a boom in discount stores and national brands. But A&P spent a lot of its limited money on expanding its own factories. For example, it built the world's largest food plant in Horseheads (town), New York. Because A&P stores were smaller, they mostly sold A&P's own brands. Customers often found popular national brands were out of stock.

- Higher labor costs. A&P stopped growing, so more of its workers had been there a long time and earned higher wages. This wasn't a problem for other chains because they were growing fast and had many newer, lower-paid workers. To cut costs, A&P tried to run stores with fewer employees. This led to long lines at checkouts and empty shelves.

Ralph Burger tried to boost sales by bringing back A&P's Plaid Stamps. But by late 1962, the sales gains disappeared. The outside directors threatened to quit unless Burger retired. When Burger left in May 1963, the stock price had dropped. Several presidents tried to turn A&P around but couldn't. In 1971, William J. Kane became president. He believed A&P could improve by focusing on basic store operations, like cleanliness and good customer service.

When his plan didn't work, Kane decided to cut prices a lot. He changed A&P into a "warehouse store" idea called W.E.O. (Warehouse Economy Outlet). The problem was that most A&P stores weren't big enough for this. The company started losing money quickly. In early 1973, the stock dropped even more. A&P left California in 1971 and Washington state in 1974. In 1974, the company also moved its headquarters from New York City to Montvale, New Jersey.

The Scott/Wood Era (1975–2001)

During the Scott/Wood era, A&P started to build modern stores. This unit was in Belleville, Ontario. Note the "sunrise" logo introduced in 1975.

In February 1975, A&P considered closing many of its 3,468 stores. Kane resigned and Jonathan Scott became the new president. Scott closed 1,500 stores in three years, leaving A&P with 1,978 stores. Scott hired many new leaders and gave more power to regional managers. In his first three years, A&P built 300 new supermarkets. They also opened their first stores that combined groceries and drugstores, called A&P Family Mart. Scott continued efforts to improve stores, focusing on cleanliness and customer service. Sales went up, even with fewer stores. Manufacturing was also reorganized. But by 1978, A&P's profits started to drop due to high inflation.

With the stock price very low, the John A. Hartford Foundation decided it couldn't wait for a turnaround. Erivan Haub, who owned the German Tengelmann Group, became interested. Haub bought 42% of A&P's stock. He then quietly bought more shares until he owned 50.3% in February 1981. Scott left, and Haub hired James Wood to be chairman. Wood had previously run the American Grand Union supermarket chain. Many leaders hired by Scott left A&P and were replaced by Wood's team.

In Germany, Tengelmann had success with Plus stores. These were smaller stores with low-priced store brands and a limited selection of meats and produce. A&P opened several Plus stores in the U.S. to use its factories and small stores. However, this idea didn't appeal to American customers, who preferred other chains with low prices on national brands.

James Wood realized A&P needed to close many more stores. In October 1981, A&P announced it would shrink to under 1,000 stores. It also closed most of its large manufacturing group. To pay for this, A&P planned to use money from its non-union pension plan. This plan had a $200 million surplus. A lawsuit was filed, but A&P still gained over $200 million. The Philadelphia division was also set to close unless unions agreed to lower pay. When unions refused, A&P started closing stores. The unions then agreed to a profit-sharing deal if A&P opened new stores under a different name. This new name was "Super Fresh", and these stores did well. A&P realized its old name wasn't as strong as it used to be.

A&P began buying stores from other chains. Starting in 1982, A&P bought several chains and kept their original names instead of changing them to A&P. A&P became profitable again in the 1980s. In 2002, however, it lost a record amount of money due to new competition, especially from Walmart. A&P closed more stores, including its large Canadian division. A&P also sold Eight O'Clock Coffee, its last manufacturing business. In 1982, Stop & Shop left New Jersey, and A&P bought most of those stores. In 1983, A&P bought Wisconsin-based Kohl's Food Stores, allowing A&P to return to Wisconsin and Illinois. In 1984, A&P bought Pantry Pride's division in Richmond, Virginia. The next year, A&P strengthened its Canadian division by closing stores in Quebec and buying Dominion Stores in Ontario. In the U.S., A&P started building larger supermarkets called A&P Future Stores.

In 1986, A&P bought Waldbaum's (stores in New York and New England) and The Food Emporium, a fancy New York City chain. In 1989, A&P bought Michigan-based Farmer Jack. A&P also tried to expand into Europe but wasn't successful. By the end of the 1980s, A&P reported a profit of 1.3% on sales of $11 billion.

In the early 1990s, A&P started to struggle again because of the economy and new competition, especially Walmart. In 1992, A&P's sales dropped, and it lost $189 million. A&P responded by improving its store brand program and updating its remaining U.S. stores. Most stores smaller than 40,000 square feet were made bigger, closed, or replaced with units from 50,000 to 80,000 square feet. The new stores included pharmacies, bigger bakeries, and more general merchandise.

A&P continued to struggle in the South. It left most of that region, selling many stores to Kroger. As a result, A&P was left with stores in only four areas: the Northeast, the Midwest (Michigan and Wisconsin), New Orleans, and Ontario. To strengthen its New Orleans division, A&P bought six Schwegmann supermarkets. However, A&P was now down to 600 stores. Christian W.E. Haub, Erivan's youngest son, became co-CEO in 1994 and CEO in 1997. In 2001, he also became chairman.

Final Years (2001–2015)

Nationwide, Walmart became very strong in the grocery business, forcing many competitors to shrink. In A&P's main Northeast region, Walmart was not yet a major grocery competitor. In 2003, after its biggest loss, A&P closed Kohl's Food Stores and its remaining stores in Vermont and New Hampshire. This reduced A&P to just over 500 stores. Also in 2003, A&P sold its Eight O'Clock Coffee division (its last factory operation) for $107 million.

In 2005, A&P sold its Canadian division (237 stores) to Metro Inc. for $1.7 billion. By 2009, the A&P name disappeared from these Canadian stores. In 2007, A&P closed its New Orleans division, leaving A&P only in the Northeast. Also in 2007, A&P bought Pathmark, a long-time rival in the Northeast, for $1.4 billion. With this purchase, A&P became the largest supermarket operator in the New York City area again. At the same time, Tengelmann reduced its shares, and Yucaipa, a major Pathmark shareholder, acquired 27.5% of A&P's shares. In 2012, A&P came out of bankruptcy and became a private company. Tengelmann ended its ownership. A&P was briefly profitable in 2013 and 2014.

The Federal Trade Commission said that because of the Pathmark purchase, A&P would have too much control in parts of Long Island and Staten Island. So, A&P had to sell some of its Waldbaum's and Pathmark stores.

When A&P celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2009, it was ranked only 21st among North American grocery retailers. Christian Haub was chairman. Eric Claus, the president and CEO, left A&P, and Sam Martin took over.

First Bankruptcy (2010)

| Year | No. of stores |

|---|---|

| 1863 | 5 |

| 1878 | 70 |

| 1900 | 400 |

| 1915 | 1,600 |

| 1930 | 15,709 |

| 1950 | 4,500 |

| 1970 | 4,000 |

| 1980 | 2,000 |

| 1990 | 1,000 |

| 2000 | 600 |

| 2010 | 395 |

| 2015 | 296 |

| All stores were closed by November 25, 2015. | |

The 2008 recession hurt many supermarkets. Customers went to discount stores more often. A&P was especially hit hard because of the debt from buying Pathmark. In June 2010, A&P stopped paying rent on closed Farmer Jack stores. In August, A&P announced it would close another 25 stores in several states. In September, A&P said it was selling seven Connecticut stores.

On December 10, 2010, rumors of bankruptcy appeared. A&P's stock price fell sharply. Two days later, A&P announced it was filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. This meant the company would reorganize its finances while still operating. A&P listed over $2.5 billion in assets and $3.2 billion in debt.

After filing for bankruptcy, A&P continued to operate. In November 2011, the company announced it would receive $490 million in funding from Yucaipa and other investment firms. This agreement helped A&P finish its restructuring and become a private company in early 2012. At this time, Christian Haub left A&P, and Tengelmann no longer owned shares.

Second Bankruptcy and Closing Down

A&P was briefly profitable again by cutting costs. However, customers were spending less money. In 2013, A&P was put up for sale but couldn't find a good buyer. In January 2014, Sam Martin resigned. In March, Paul Hertz became CEO and President. On January 15, 2015, a trade publication reported that A&P was still for sale.

There were rumors that several companies were interested. However, no good offers were received. In May, rumors spread that A&P was in more financial trouble. It had a huge loss for the previous year and was losing more business to better-managed competitors. As customers stayed away, A&P considered filing for bankruptcy a second time.

There were rumors that A&P would sell all stores far from its main offices, shrinking the company to about 100 stores. Other rumors said the company would sell all its stores. Rumors also suggested a total closing down, selling the company in pieces. The company remained for sale as a whole, but received no bids for any of its stores.

On July 19, 2015, A&P filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection again. It immediately closed 25 stores that were not doing well. The next day, A&P announced that 76 of its stores were sold to Albertsons. Stop & Shop bought 25 stores. The Key Food co-operative bought 23 stores. Other local grocers also bought stores. All supermarkets were closed by November 25, 2015. The last part of A&P, "Best Cellars at A&P" (liquor stores), had its stores sold in summer 2016.

Store Design and Features

The A&P Historical Society says early stores were "splendid emporiums." They were painted bright red and had a large gas light "T" sign. Inside, there were crystal chandeliers, tin ceilings, and walls with Chinese-style panels. A clerk stood behind a long counter to help customers. Self-service wasn't common until the 1930s. The cashier's area looked like a pagoda. When A&P started offering gifts, there were big shelves to show them off.

After John Hartford took over marketing in the 1900s, A&P started offering S&H Green Stamps. This freed up space for more groceries. The economy stores John Hartford created in 1912 were simple. They were usually 600 square feet and had basic shelves and a small ice box. A&P only signed short leases so they could quickly close stores that weren't making money.

In the early 1920s, A&P opened stores that sold groceries, meat, and produce. These eventually became supermarkets in the 1930s. On average, each supermarket replaced six older, smaller stores. A&P's policy of short leases meant store designs varied a lot until the 1950s. In the mid-20th century, A&P stores were much smaller than other chains. As late as 1971, half of A&P stores were under 8,000 square feet.

During the Scott era, store design became more modern and controlled from the main office. A&P created four different store sizes. Family Mart stores were combined grocery and drug stores with 40,000 square feet of space.

Futurestore Concept

During the Wood era, A&P developed the "Futurestore" idea. These supermarkets used black-and-white decorations. Family Mart stores were used to test this new design.

Futurestore was one of two new store ideas A&P launched in the 1980s. Futurestore's first supermarket opened in the New Orleans area in 1984. The first A&P store to be changed to the Futurestore format was in New Jersey in 1985.

The Futurestore idea spread to A&P stores in the southeastern U.S. and the Mid-Atlantic region (operating as Super Fresh in Philadelphia). But by the late 1980s, all Futurestores were renamed or closed.

Futurestores usually had the newest gourmet food sections and electronic services in wealthy neighborhoods. Their features were more focused on fancy and special foods than a regular A&P. Futurestores also had more modern equipment.

Since the idea wasn't used widely, A&P stopped using the Futurestore name. Some stores closed, and others were changed to A&P or Sav-A-Center. Many customers felt Futurestore didn't have the same style as other fancy food stores.

Pharmacies in Stores

In the mid-1990s, A&P started adding pharmacies to its stores. It focused on building units that were 45,000 to 65,000 square feet.

Overseas Stores

In the early 1980s, there was talk of A&P opening a store in Saudi Arabia. A&P Preservation reported in 2018 that A&P did open a store in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The name was licensed to local operators. The store was likely later changed to a Saudi version of Safeway.

Different Store Names

For most of its history, A&P used only the A&P name for its stores. This changed during the Scott and Wood eras. A&P created new chains or kept the original names of chains it bought. Here are some of the store names A&P used:

- Family Mart: Started in 1977, these were large grocery stores with pharmacies. They were initially successful.

- Plus: In Germany, Tengelmann had small, low-cost "Plus" stores. After buying A&P, Tengelmann changed some smaller A&P stores to the Plus idea.

- Super Fresh: When A&P planned to close its Philadelphia division in 1981–82, unions offered to buy many stores. A&P agreed to a new labor deal that included profit-sharing. The stores were operated under the new name Super Fresh. These stores did well.

- Food Basics (US & CA): In the early 2000s, A&P changed some unprofitable stores into "no-frills" supermarkets called Food Basics. They offered basic groceries at lower prices.

- Kohl's Food Stores: A&P bought these Wisconsin-based stores in 1983. A&P closed Kohl's Food Stores in 2003.

- Dominion (Canada): In 1985, A&P bought the Dominion chain in Canada. Dominion was sold in 2005.

- The Food Emporium: A&P bought this 26-store New York City chain in 1985. It was founded in 1919 and focused on wealthy areas. Food Emporium stores were still operating when A&P closed down.

- Waldbaum's: This chain was bought in 1986. It was founded in 1904 and expanded from New York City into Long Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. Many Waldbaum's stores were still open when A&P closed.

- Farmer Jack: This 79-store chain in Detroit was bought by A&P in 1989. By 2007, all Farmer Jack stores were sold or closed.

- Sav-A-Center: This name was used for 20 supermarkets in the New Orleans, Louisiana, area. Many stores were damaged by Hurricane Katrina. In 2007, A&P decided to leave the New Orleans area and sold its remaining Sav-A-Center stores.

- Pathmark: This was a large New York-area chain and a major competitor of A&P. It was bought by A&P in 2007. Many Pathmark stores were still open when A&P closed down.

A&P's Own Brands

A&P, 246 Third Avenue, Manhattan, 1936. Note the prominent ads for A&P's private brands.

When A&P started, there were no branded food products. Stores sold food in bulk. In 1870, A&P was one of the first to sell a branded, pre-packaged food product: "Thea-Necter" tea. In 1885, the name "A&P" appeared on baking powder. In the 1880s, the company named its coffee "Eight-O'Clock." When A&P moved its headquarters to Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1907, it included a bakery and coffee-roasting area.

A&P became one of the country's largest food makers. This happened partly because of a 1915 court decision that said manufacturers could set retail prices. To keep prices low, A&P focused on its own private label goods. By 1962, A&P had 67 factories. It later combined many into a huge 1.5 million-square-foot facility in Horseheads, New York. This was the largest food manufacturing plant in the world under one roof.

As late as 1977, A&P's own brands made up 25% of its sales. A&P's factories produced over 40% of these. That year, A&P's manufacturing group alone made $750 million in sales from its 23 plants.

Until 1975, A&P's production was handled by four separate divisions:

- Bakery (Grandmother's, Marvel, and Jane Parker): A&P became America's largest baker, with 37 plants. By 1977, there were only seven bakeries, and the division closed in 1981–82.

- Coffee (Eight O'Clock, Bokar, Red Circle): In 1919, A&P created the "American Coffee Company" and built roasting and grinding facilities. The coffee operation lasted until 2003.

- Dairy: This division started in 1922 when A&P bought a company to make evaporated milk. By 1977, the division had three dairies and other plants.

- Grocery (Quaker Maid, Ann Page, Our Own Tea): In 1907, A&P opened a vegetable canning factory. After World War I, A&P bought salmon canneries in Alaska. A&P then acquired facilities to make many canned goods, frozen foods, nuts, tea bags, pasta, peanut butter, and more. A&P also had a printing plant for labels and promotional materials.

In the mid-1990s, A&P introduced a new simple store brand called America's Choice. This brand lasted until the company closed in 2015. (In Canada, the brand was called "Master Choice.")

In 2008 and 2009, A&P added the environmentally friendly Green Way brand, the fancy Food Emporium Trading Company brand, and the low-cost Food Basics alternative.

Woman's Day Magazine

What is now Woman's Day magazine started as a free leaflet from A&P in 1931. It had menus inside. In 1937, it became a full magazine sold only in A&P stores for 5 cents. Its circulation reached 3 million in 1944 and 4 million by 1958, when it was sold to another publisher.

A&P in Pop Culture

- In the movie Breaking Away, Dennis Quaid's character sings, "When I die I want to be buried in the parking lot of an A&P."

- In the HBO series Boardwalk Empire, characters Gillian Darmody and Roy Phillips have dinner with A&P executives.

- In Tim Burton's movie Big Eyes, Margaret Keane goes into an A&P and sees her paintings being sold.

- The 1981 song "Christmas Wrapping" by "The Waitresses" includes the line, "A&P has provided me with the world's smallest turkey."

- From 1924 to 1936, A&P sponsored the radio show The A&P Gypsies.

- A&P also sponsored Kate Smith's radio program for a long time. The popular singer became an A&P spokesperson.

- The store is the setting for John Updike's 1961 short story, "A&P".

- A&P partnered with the Lifetime Network to produce the food-reality series Supermarket Superstar in 2013.

- In the 1988 movie Scrooged, Bill Murray's character says, "Look up A&P. If it's not under "A", then look under "P". A&P was supposed to bring over turkeys for the shelter."

- In the 1989 film Born on the Fourth of July, Ron Kovic works at an A&P supermarket. His father is the manager. He asks his high school crush to the prom inside an A&P.

- In the 2001 book Good to Great, A&P was one of the companies studied against its rival Kroger.

- In the 2009 episode of Mad Men, "The Arrangements", a police officer tells Betty Draper that her father "collapsed in line at the A&P."

- In the 2004 episode of Without a Trace, "Wannabe", Emily Levine says, "Well at least her mom doesn't work at the checkout counter at the A&P."

- In the 2022 movie based on the novel White Noise, A&P is shown as the characters' favorite grocery store.

See Also

- List of supermarket chains in the United States

- Retail apocalypse

- List of retailers affected by the retail apocalypse