Aliger gigas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Aliger gigas |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| A live subadult individual of Aliger gigas, in situ surrounded by turtle grass | |

|

|

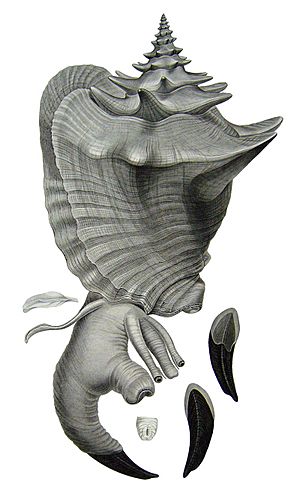

| A dorsal view of an adult individual of A. gigas from Chenu, 1844 | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Subclass: | Caenogastropoda |

| Order: | Littorinimorpha |

| Family: | Strombidae |

| Genus: | Aliger |

| Species: |

A. gigas

|

| Binomial name | |

| Aliger gigas (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Strombus gigas Linnaeus, 1758 |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Aliger gigas, often called the queen conch, is a very large sea snail. It is a type of mollusc that lives in the ocean. You can find these amazing creatures in the Caribbean Sea and the tropical northwestern Atlantic Ocean, from Bermuda all the way to Brazil. They can grow quite large, with their shells reaching up to 35.2 centimeters (about 14 inches) in length! The queen conch is related to other large conchs like the goliath conch and the rooster conch.

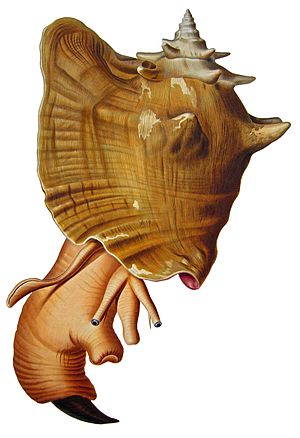

Queen conchs are herbivorous, meaning they eat plants. They mostly munch on seagrass and algae that grow on the sandy seafloor. They also eat decaying plant bits. These snails usually live in seagrass beds, which are like underwater meadows. The look of their home changes a bit as they grow older. Adult conchs have a very big, strong, and heavy shell. It has bumpy spines on its "shoulder" and a wide, thick outer lip. The inside opening of the shell is usually a pretty pink or orange color. The outside of the shell is sandy-colored, which helps them hide. Young conchs don't have this wide lip; it only grows when they are old enough to have babies. The thicker the lip, the older the conch is.

The soft parts of the queen conch are similar to other snails. They have a long snout and two eyestalks with good eyes. They also have other feelers, a strong foot, and a hard, claw-shaped "door" called an operculum.

Many small animals live on or near the queen conch's shell, like slipper snails and porcelain crabs. A special type of cardinalfish called the conchfish even hides inside its shell for safety! Queen conchs can also have tiny parasites. Many animals like to eat queen conchs, including other large sea snails, octopus, starfish, crustaceans, fish, sea turtles, and nurse sharks. They are a very important food source for big predators like sea turtles. Humans have also been catching and eating conchs for a very long time.

People often sell queen conch shells as souvenirs or use them as decorations. Long ago, Native Americans and Caribbean people used parts of the shell to make tools.

Because so many people want queen conchs, their trade is now controlled by an agreement called CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). While the species isn't endangered everywhere in the Caribbean, it is threatened in many places because too many are being caught, which is called overfishing.

Naming the Queen Conch

How it Got its Name

The queen conch was first described in 1758 by a Swedish scientist named Carl Linnaeus. He is famous for creating the system we use today to name living things with two names (like Homo sapiens for humans). Linnaeus named this snail Strombus gigas. This name stuck for over 200 years! The word gigas comes from ancient Greek and means "giant," which makes sense because this snail is huge compared to most other snails.

Over time, scientists learned more about the queen conch and its relatives. They sometimes change scientific names as they discover new things about how species are related. Today, the official scientific name for the queen conch is Aliger gigas.

Common Names Around the World

This amazing snail has many common names! In English, it's usually called "queen conch" or "pink conch." In Spanish-speaking countries, it has names like caracol rosa, caracol rosado, caracol de pala, cobo, botuto, guarura, caracol reina, lambí, and carrucho.

What a Queen Conch Looks Like

Its Shell

A grown queen conch shell can be about 15 to 31 centimeters (6 to 12 inches) long. The biggest ever found was 35.2 centimeters (about 14 inches). They reach their full length in about three to five years. But even after they stop growing longer, their shells keep getting thicker! This makes the shell very strong and heavy, which helps protect the conch. The thicker the shell, the older the conch usually is.

The shell has a spiral top part called the spire. The opening of the shell, called the aperture, is usually a pale pink color. It can also be cream, peach, or yellow, and sometimes even a deep red. The outside of the shell has a thin, brownish layer called the periostracum.

The way a conch shell looks can change depending on where it lives. Things like food, temperature, water depth, and even predators can affect its shape. For example, young conchs grow stronger shells if there are predators around. Conchs in deeper water tend to have wider and thicker shells with fewer but longer bumps.

Young queen conch shells look very different from adult ones. They don't have the wide, flared lip. Instead, their shells are simple and pointed, like a cone. In Florida, young conchs are sometimes called "rollers" because waves can easily roll their light shells. Adult shells are too heavy and oddly shaped to roll. The flared lip of the shell gets thicker and thicker until the conch dies.

Conch shells are mostly made of calcium carbonate, which is the same material as chalk or limestone.

Old Drawings of Shells

Old books from the 1700s and 1800s show beautiful drawings of queen conch shells. These drawings highlight the bumpy spire and the wide, wing-like outer lip that makes the shell so special.

Soft Body Parts

The queen conch has a long, stretchy snout and two eyestalks that come out from its base. At the end of each eyestalk is a large, well-developed eye with a black pupil and a yellow iris. There's also a small feeler near each eye. If an eye is lost, it can grow back! Inside its mouth, the conch has a tough, ribbon-like tongue covered in tiny teeth, called a radula. Both the snout and eyestalks have dark spots. The edge of its soft body, called the mantle, is dark in the front and lighter gray in the back. The tube it uses to breathe and filter water, called the siphon, is orange or yellow.

How it Moves

The queen conch has a big, strong foot. It's mostly white, but has brown spots near the edge. Attached to the back of its foot is a dark brown, hard, sickle-shaped "door" called an operculum.

Queen conchs move in a very unusual way, almost like they are pole vaulting! First, they stick the pointed end of their operculum into the sand. Then, they stretch their foot forward, lift their shell, and throw it forward in a leaping motion. This special way of moving helps them climb, even on vertical surfaces like concrete. It might also help them avoid predators by not leaving a continuous trail for them to follow.

Life of a Queen Conch

Each queen conch is either male or female. Females are usually bigger than males. After mating, the female lays her eggs in long, jelly-like strings that can be as long as 23 meters (75 feet)! These strings are laid on bare sand or seagrass. The sticky eggs mix with sand to form compact egg masses. A single female can lay 8 to 9 egg masses in a season, each with 180,000 to 460,000 eggs, and sometimes even up to 750,000 eggs! Females can lay eggs multiple times during the reproductive season, which runs from March to October, with the most activity from July to September.

Queen conch babies hatch from their eggs after 3 to 5 days. When they hatch, they are tiny larvae called veligers. They have two lobes and float in the water, feeding on tiny plants called phytoplankton. After about 16 to 40 days, they change into their adult form and settle on the seafloor. For their first year, they usually stay buried in the sand.

Queen conchs become old enough to reproduce at about 3 to 4 years old, when their shells are about 18 centimeters (7 inches) long. They usually live for about 7 years, but in deeper waters, they can live for 20 to 30 years, and some might even reach 40 years old! Younger conchs are more likely to be eaten by predators because their shells are not as thick.

Where Queen Conchs Live and What They Do

Where They Live

Queen conchs live in the warm, tropical waters of the Western Atlantic Ocean. This includes the coasts of North and Central America, and all around the Caribbean Sea. You can find them in places like Aruba, Barbados, the Bahamas, Belize, Bermuda, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Panama, Jamaica, Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Florida in the United States, and Venezuela.

Their Home

Queen conchs live in water that is usually 0.3 to 18 meters (1 to 60 feet) deep, but they can be found as deep as 25 to 35 meters (80 to 115 feet). They like to live in seagrass meadows and on sandy bottoms. They are often found near turtle grass and manatee grass. Young conchs prefer shallow seagrass beds closer to shore, while adults like deeper areas with more algae and seagrass.

Queen conchs often live in groups that can have thousands of individuals.

What They Eat

For a long time, people thought conchs were meat-eaters, but that's not true! Like other snails in their family, queen conchs are herbivorous. They eat large macroalgae (like red algae), seagrass, and tiny single-celled algae. They also eat decaying plant matter. One of their favorite foods is a green algae called Batophora oerstedii.

Who They Interact With

Some animals live with queen conchs in a way that helps them but doesn't harm the conch. This is called a commensal relationship. For example, certain slipper shells and porcelain crabs live on the conch's shell. A small fish called the conch fish sometimes hides inside the conch's shell for protection.

Queen conchs can also have tiny, single-celled parasites that live in their digestive system.

Many animals like to eat queen conchs. These include other carnivorous snails like the horse conch and the trumpet triton. Crustaceans like blue crabs, box crabs, giant hermit crabs, and spiny lobsters also hunt them. Sea stars, octopus, eagle rays, nurse sharks, and different types of fish (like permit and porcupine fish) also prey on them. Loggerhead sea turtles and humans are also important predators of the queen conch.

How People Use Queen Conchs

Conch meat has been eaten for hundreds of years, especially in the West Indies and Southern Florida. People eat it raw, marinated, chopped in salads, or cooked in dishes like chowder, fritters, soups, and stews. In many places, the meat is called lambí. While most conch meat is for people, it's sometimes used as fishing bait. The queen conch is a very important fishing resource in the Caribbean.

Long ago, Native Americans and Caribbean people used conch shells in many ways. They made tools like knives, axe heads, and chisels. They also made jewelry, cooking tools, and used the shells as blowing horns. The Aztecs even used conch shells in their jewelry and believed the sound of conch trumpets was divine.

When explorers brought queen conch shells to Europe, they quickly became popular decorations. Today, people still use them for crafts. Shells are made into cameos, bracelets, and lamps. They are also used as doorstops or just as pretty decorations. Because they are so popular, exporting the shells is now controlled by the CITES agreement. You can even see queen conch shells on coins and stamps!

Very rarely, about 1 in 10,000 conchs, you might find a special pearl inside its shell. These conch pearls come in different colors, matching the inside of the shell, but pink ones are the most valuable. They are considered semi-precious gems and are popular with tourists. The best ones are used to make necklaces and earrings. Unlike most pearls, conch pearls are not shiny or iridescent. It's almost impossible to farm these pearls because of how delicate the conch is.

Scientists at MIT are even studying the unique structure of the conch shell to learn from it.

Protecting the Queen Conch

What Threatens Them

The number of queen conchs has been dropping quickly in many parts of the Caribbean. This is mainly because people want their meat and shells so much. One big problem is overfishing. There's almost as much meat in large young conchs as in adults, but only adults can reproduce. So, if too many young conchs are caught before they can have babies, the population can't grow back. In many places, fishers catch young conchs even before they get a chance to mate.

In the United States (Florida), it's against the law to catch queen conchs for fun or for business. In other places where it's allowed, there are rules to only catch adult conchs. The idea is to let them have enough time to reproduce. But sadly, many fishers don't follow this rule.

Because of overfishing, many conch groups are now too small to reproduce well. A study in 2019 warned that overfishing could make queen conchs disappear in as little as ten years. If the conch fishing industry collapses, it could mean over 9,000 people in the Bahamas lose their jobs. Trade from many Caribbean countries is not sustainable, meaning too many conchs are being taken. By 2001, queen conch populations in at least 15 Caribbean countries were being overfished. Catching conchs illegally, including in other countries' waters, is a big problem. There's an international effort called the "International Queen Conch Initiative" to help manage this species. In 2019, the Bahamas even suggested stopping conch exports and hiring more staff to enforce rules.

Another serious threat is ocean acidification. This means the ocean is becoming more acidic because of rising CO2 levels in the air. This is especially bad for animals with shells made of calcium carbonate, like conchs. The baby conchs are very sensitive to these changes in ocean acidity.

In 2022, a US government agency called NOAA looked at conch populations. They found that the species has a moderate risk of disappearing in the next 30 years.

How They Are Protected

Each country usually manages its own queen conch fishing rules. In the United States, it's illegal to catch them in Florida and nearby federal waters. While there isn't one big organization for the whole Caribbean, places like Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands have their own rules. In 2014, the queen conch was added to a special list under the Cartagena Convention. This means countries need to take special steps to protect and help them recover.

The queen conch is also listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). This means that international trade (importing or exporting) of conchs and their parts is controlled by a permit system. CITES has even recommended that some countries stop importing conchs from places like Honduras, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic because of unsustainable fishing. However, you can still get conch meat from other countries like Jamaica and Turks and Caicos, which have better-managed conch fisheries. For conservation, the government of Colombia bans catching and eating conchs between June and October. The Bahamas National Trust is also working to teach teachers and students about conch protection, even with a catchy pop song called Conch Gone!

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Caracol rosado para niños

In Spanish: Caracol rosado para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |