Anglo-Saxon London facts for kids

The history of Anglo-Saxon London tells the story of the city of London during the Anglo-Saxon period, from the 7th to the 11th centuries.

The old Roman city of Londinium was left empty around the late 5th century. But its strong walls, known as the London Wall, stayed standing. By the early 7th century, a new Anglo-Saxon settlement called Lundenwic grew about a mile west of Londinium. It was located north of where the Strand is today. Lundenwic came under the control of Mercia around 670. After Offa of Mercia died in 796, Mercia and Wessex fought over who would control it.

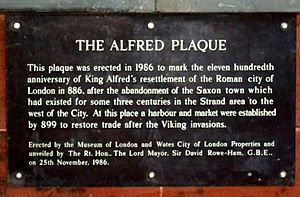

Viking attacks became common from the 830s. A Viking army is thought to have stayed inside the old Roman walls during the winter of 871. Alfred the Great brought London back under English control in 886. He also made its defenses stronger. The old Roman walls were fixed, and the defensive ditch was dug again. The old Roman city then became the main place where people lived. This city was now called Lundenburg, marking the start of the City of London's history. Sweyn Forkbeard attacked London without success in 996 and 1013. But his son Cnut the Great finally took control of London and all of England in 1016.

Edward the Confessor, Cnut's stepson, became king in 1042. He built Westminster Abbey, the first large Romanesque church in England. It was opened in 1065. He also built the first Palace of Westminster. These buildings were just up-river from the city. Edward's death led to a fight over who would be king. This eventually caused the Norman invasion of England.

Contents

Lundenwic: London's First Anglo-Saxon Town

The Roman city of London was left empty in the early Anglo-Saxon period. We have almost no clear information about what happened in the London area from about 450 to 600 AD. Early Anglo-Saxon settlements were not built on the site of the old Roman city. However, the Roman London Wall stayed standing. Instead, by the 670s, a port town called Lundenwic began to grow. This was in the area we now call Covent Garden.

In the early 8th century, a writer named the Venerable Bede described Lundenwic. He called it "a trading centre for many nations who visit it by land and sea." The Old English word wic meant "trading town." It came from the Latin word vicus. So, Lundenwic simply meant "London trading town."

For many years, archaeologists wondered where early Anglo-Saxon London was. They found little proof of people living inside the Roman city walls during this time. But in the 1980s, archaeologists found Lundenwic again. They dug up a large Anglo-Saxon settlement in the Covent Garden area. These digs showed that the settlement started in the 7th century. It covered a large area, stretching along the north side of the Strand. This area went from the National Gallery site in the west to Aldwych in the east.

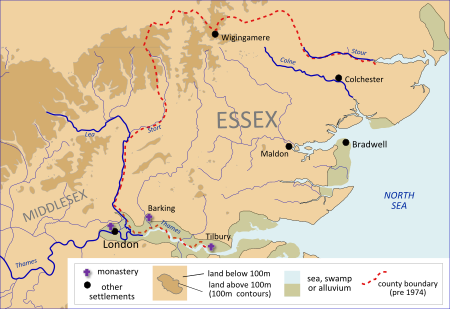

By about 600 AD, Anglo-Saxon England was split into many small kingdoms. These kingdoms later became known as the Heptarchy. From the mid-6th century, London became part of the Kingdom of Essex. This kingdom reached as far west as St Albans. For a time, it also included Middlesex and Surrey.

In 604, Sæberht of Essex became a Christian. London then received Mellitus, its first bishop after the Romans left. At this time, Essex was loyal to Æthelberht of Kent. Under Æthelberht, Mellitus started the first cathedral of the East Saxons. People traditionally say it was built on the site of an old Roman temple. The first church was likely small. It might have been destroyed after Mellitus was forced out of the city in 616. Most people in London remained pagan for much of the 7th century. The bishop's role was only filled sometimes. The bishopric of London was finally set up for good in 675. This is when Theodore of Tarsus, the Archbishop of Canterbury, made Earconwald bishop.

Lundenwic came under the direct control of Mercia around 670. This happened as Essex became smaller and less important. After Offa of Mercia died in 796, Mercia and Wessex fought over who would control Lundenwic.

Viking Attacks on London

London faced many attacks from Vikings. These attacks became more and more common from about 830 onwards. In 842, London was attacked in a raid that a writer called "the great slaughter." In 851, another group of raiders, said to have 350 ships, came to rob the city.

In 865, the Viking Great Heathen Army launched a huge invasion. They took over East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria. They almost controlled most of Anglo-Saxon England. By 871, they had reached London. It is believed they camped inside the old Roman walls during the winter of that year. We are not sure exactly what happened then. But London might have been under Viking control for a while.

In 878, forces from Wessex, led by Alfred the Great, defeated the Vikings. This happened at the Battle of Ethandun. They forced the Viking leader Guthrum to ask for peace. The Treaty of Wedmore and a later agreement, the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum, divided England. This created the Danelaw, which was controlled by the Danes.

Lundenburg: London Reborn

English rule in London was brought back by 886. King Alfred quickly started building fortified towns, called burhs, across southern England. This was to make his kingdom's defenses better. London was one of these towns. Within ten years, a settlement was set up again inside the old Roman walls. It was now called Lundenburg. The old Roman walls were fixed, and the defensive ditch was dug again. These changes truly marked the beginning of the modern City of London. Its borders are still partly defined by these ancient city walls.

As Lundenburg moved back inside the Roman walls, the original Lundenwic was mostly left empty. Over time, it got the name Ealdwic, meaning 'old settlement'. This name still exists today as Aldwych.

London in the 10th Century

Alfred made his son-in-law, Earl Æthelred of Mercia, the Governor of London. Æthelred was the heir to the destroyed kingdom of Mercia. Alfred also set up two defended Boroughs to protect the bridge. This bridge was probably rebuilt around this time. The southern end of the bridge became Southwark, or Suthringa Geworc, meaning 'defensive work of the men of Surrey'. From this point, the city of London began to develop its own unique local government.

After Æthelred died, London came under the direct control of English kings. Alfred's son Edward the Elder won back much land from Danish control. By the early 10th century, London had become an important place for trade. Even though the main political center of England was Winchester, London became more and more important. King Æthelstan held many royal meetings in London. He also issued laws from there. Æthelred the Unready liked London as his capital. He issued his Laws of London from there in 978.

The Vikings Return and Cnut's Rule

It was during King Æthelred's rule that Vikings started their raids again. These were led by Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark. London was attacked without success in 994. But many more raids followed. In 1013, London faced a long siege. King Æthelred was forced to run away to another country.

Æthelred came back with his friend, the Norwegian king Olaf. They took London back. A Norse saga (an old story) tells of a battle during the Viking occupation. It says King Æthelred returned to attack Viking-held London. According to the story, the Danes stood on London Bridge. They threw spears down at the attackers.

But the attackers were not scared. They pulled the roofs off nearby houses. They held these roofs over their heads in their boats. This protected them. They were able to get close enough to the bridge to tie ropes to its supports. Then, they pulled the bridge down. They defeated the Vikings and ended their control of London. Some people think the nursery rhyme "London Bridge is Falling Down" comes from this event. After Æthelred died on April 23, 1016, his son Edmund Ironside was declared king.

Sweyn's son Cnut the Great continued the attacks. He raided Warwickshire and moved north across eastern Mercia in early 1016. Edmund stayed in London, still safe behind its famous walls. He was chosen as king after Æthelred died. But Cnut came back south. The Danish army seemed to split. Some dealt with Edmund, while others surrounded London.

A battle at Penselwood in Somerset and another at Sherston in Wiltshire were fought over two days. Neither side won clearly. Edmund was able to help London for a short time. He drove the enemy away and defeated them after crossing the Thames at Brentford. He lost many soldiers. So, he went back to Wessex to get new troops. The Danes again surrounded London. But after another failed attack, they went into Kent. The English attacked them there, and a battle was fought at Otford.

On October 18, 1016, Edmund's army fought the Danes. This happened as the Danes were going back to their ships. This led to the Battle of Assandun. During the fight, Eadric Streona left the battle with his forces. This caused a big English defeat. Edmund ran west. Cnut chased him into Gloucestershire. Another battle was probably fought near the Forest of Dean.

On an island near Deerhurst, Cnut and Edmund met to talk about peace. Edmund had been hurt. They agreed that all of England north of the Thames would belong to the Danish prince. All the land to the south, including London, would stay with the English king. It was also agreed that Cnut would become king of all England when Edmund died.

Edmund died on November 30, just weeks after the agreement. Some sources say Edmund was murdered. But we do not know how he died. According to the agreement, Cnut became king of all England. He was crowned in London at Christmas. The nobles recognized him in January of the next year in Oxford.

Cnut's sons, Harold Harefoot and Harthacnut, ruled briefly after him. Then, the Saxon royal family was restored. This happened when Cnut's stepson Edward the Confessor became king in 1042.

Edward the Confessor and the Norman Invasion

After Harthacnut died on June 8, 1042, Godwin, the most powerful English earl, supported Edward. Edward then became king. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes how popular he was when he became king. It says "before he [Harthacnut] was buried, all the people chose Edward as king in London." Edward was crowned at the cathedral of Winchester. This was the royal seat of the West Saxons. The crowning happened on April 3, 1043.

Modern historians do not agree with the old idea that Edward mainly used Norman friends. But he did have foreigners in his household. The most important was Robert of Jumièges. He came to England in 1041. He became Bishop of London in 1043. According to the Vita Ædwardi Regis (a book about Edward's life), he became "always the most powerful confidential adviser to the king."

When Edward made Robert of Jumièges the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1051, he chose a skilled craftsman named Spearhafoc to replace Robert as bishop of London. However, Spearhafoc was never officially made bishop.

Edward's liking for Normans is most clear in his biggest building project. This was Westminster Abbey. It was the first Norman Romanesque church in England. Building started between 1042 and 1052. It was meant to be a royal burial church. It was opened on December 28, 1065. It was finished after Edward's death around 1090. This building was torn down in 1245 to make way for King Henry III's new building, which is still there today. Edward's building is shown in the Bayeux Tapestry. It looked very similar to Jumièges Abbey in Normandy. That abbey was built at the same time. Robert of Jumièges must have been very involved in both buildings.

After Edward died in 1066, there was no clear heir to the throne. His cousin, Duke William of Normandy, claimed he should be king. The English Witenagemot (a council of wise men) met in the city. They chose Edward's brother-in-law, Harold Godwinson, as king. Harold was crowned in Westminster Abbey. William was very angry about this. He then invaded England.

Images for kids

-

A mention of Lunden in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

-

Statue of Alfred the Great in Wantage, his birthplace.

-

A gold coin probably minted in London during the reign of Æthelred the Unready, showing him wearing armour

-

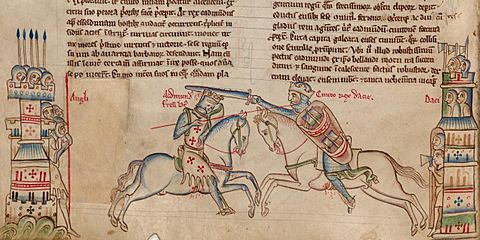

Medieval illustration by Matthew Paris, depicting Edmund Ironside (left) and Cnut (right).