Black Prince's chevauchée of 1356 facts for kids

The Black Prince's chevauchée of 1356 was a huge mounted raid led by Edward, the Black Prince. It happened between August 4 and October 2, 1356. This raid was part of the long Hundred Years' War between England and France.

The war had started in 1337. But a truce and the terrible Black Death plague had slowed down the fighting since 1347. In 1355, the French king, John II, decided to restart the full war. That autumn, while Edward III threatened northern France, his son, Edward of Woodstock (the Black Prince), led a huge raid. His Anglo-Gascon army marched from Gascony for 675 miles (1,086 km) to Narbonne and back. The French avoided a big battle, even though they suffered huge economic damage.

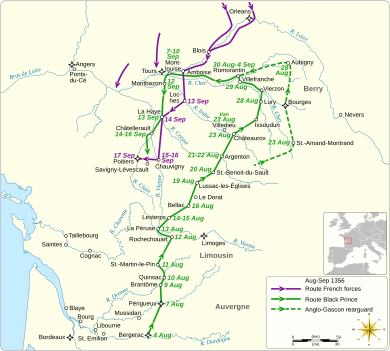

In 1356, the Black Prince planned another similar raid. This time, it was part of a bigger plan to attack France from several directions. On August 4, 6,000 Anglo-Gascon soldiers headed north from Bergerac. They destroyed a wide area of French land and sacked many towns. They hoped to meet two other English armies near the Loire River. But by early September, the Anglo-Gascons faced a much larger French royal army alone.

The Black Prince pulled back towards Gascony. He was ready to fight, but only on ground he chose. King John wanted to fight. He hoped to cut off the Anglo-Gascons' supplies and force them to attack him. The French did manage to cut off the Prince's army. But then they decided to attack his strong defensive position anyway. They feared he might escape, and it was also a matter of honor. This battle became known as the Battle of Poitiers.

Between 14,000 and 16,000 French troops attacked on the morning of September 19. They attacked in four waves. The Anglo-Gascons defeated each wave in a long battle. They partly surrounded the last French attack. They even captured the French King and one of his sons. In total, 5,800 French soldiers were killed. Another 2,000 to 3,000 men-at-arms were captured. The remaining French soldiers scattered. The Anglo-Gascons continued their retreat to Gascony.

The next spring, a two-year truce was agreed. The Black Prince took King John to London. Talks to end the war and ransom John took a long time. Edward launched another campaign in 1359. Both sides then made compromises. The Treaty of Brétigny was agreed. Huge areas of France were given to England. The Black Prince would rule them personally. John was ransomed for three million gold écu. At the time, this seemed to end the war. But the French restarted fighting in 1369. They recaptured most of the lost land. The war finally ended in 1453, with a French victory.

Quick facts for kids Chevauchée of the Black Prince |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Hundred Years' War | |||||||

Near-contemporary image of the Battle of Poitiers |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6,000 | Unknown but large | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Few | Heavy | ||||||

Contents

The Hundred Years' War Begins

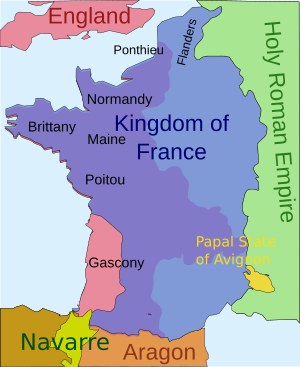

Since the Norman Conquest of 1066, English kings had lands in France. This made them vassals, or loyal subjects, of the French kings. There were many disagreements between Philip VI of France (who ruled from 1328 to 1350) and Edward III of England (who ruled from 1327 to 1377).

On May 24, 1337, Philip's Great Council in Paris decided something big. They agreed that Edward III's lands in France should be taken back. They said Edward was not following his duties as a vassal. This decision started the Hundred Years' War. This war would last for 116 years!

The most important French land still held by the English was Gascony. It was in the southwest of France. Gascony was very important because taxes on wine from there brought in more money than all other English taxes combined. Bordeaux, the capital of Gascony, had over 50,000 people. This was more than London at the time. Bordeaux was also probably richer.

Even though Gascony caused the war, Edward III had few soldiers to defend it. Most of the time, the Gascons had to defend themselves. They were often under pressure from the French. Gascony could usually gather 3,000–6,000 men. Most of these were foot soldiers. Up to two-thirds of them were busy guarding forts. In 1345 and 1346, Henry, Earl of Lancaster, led successful campaigns. The combined English and Gascon forces pushed the fighting away from the heart of Gascony.

The French port of Calais fell to the English in August 1347. This happened after the Crécy campaign. Soon after, the Truce of Calais was signed. Both countries were running out of money. In the same year, the Black Death reached France and England. This terrible plague killed many people in Western Europe. It hit England even harder. This disaster, which lasted until 1350, stopped the fighting for a while. The truce was extended many times. But there were still naval clashes and small fights. Fighting was especially fierce in southwest France.

A treaty to end the war was discussed in Guînes. It was signed on April 6, 1354. However, the French king, John II (who ruled from 1350 to 1364), decided not to approve it. So, it did not take effect. It became clear that by the summer of 1355, both sides would fight a full-scale war again. In April 1355, Edward and his council decided to attack France. They planned offensives in northern France and Gascony. King John tried to put many soldiers in his northern towns. He also tried to gather a large army. But he could not, mostly because he lacked money.

The Black Prince Arrives

Edward's oldest son, Edward of Woodstock, was put in charge of the Gascon army. He started gathering men, ships, and supplies. He arrived in Bordeaux on September 20, 1355. He had 2,200 English soldiers with him. The next day, he was officially named the king's leader in Gascony. He had full power to make decisions. Gascon nobles joined him, making his army 5,000 to 6,000 strong. They also brought equipment for building bridges and a large supply train.

On October 5, Edward began a `chevauchée`. This was a large-scale mounted raid. The Anglo-Gascon army marched from Bordeaux in English-held Gascony. They went 300 miles (480 km) to Narbonne and then back to Gascony. They destroyed a wide area of French land. They also sacked many French towns. John, Count of Armagnac, who led the French forces there, avoided battle. There was little fighting. No land was captured. But France suffered huge economic damage. Historian Clifford Rogers said "the importance of the economic attrition of the `chevauchée` can hardly be exaggerated." The army returned to Gascony on December 2. They had marched 675 miles (1,086 km).

The English army continued attacking after Christmas. They captured over 50 French towns or forts in four months. These included important towns near Gascony's borders. Some were even more than 80 miles (130 km) away. French commanders did not try to stop them. Several French nobles in the area joined the English side. The Black Prince accepted their loyalty on April 24, 1356.

Money and excitement for the war were running out in France. Historian Jonathan Sumption said the French government was "falling apart in jealous anger." A writer at the time said "the King of France was severely hated in his own realm." Arras rebelled and killed loyalists. The main nobles of Normandy refused to pay taxes. On April 5, 1356, King John arrested Charles II, king of Navarre. Charles was known for being disloyal. John also arrested nine other critics. Four were quickly executed. Several Norman nobles then asked Edward for help.

Edward saw a chance. He sent an army, which was planned for Brittany, to Normandy instead. This army was led by Lancaster. In late June, Lancaster set off with 2,300 men. He pillaged and burned his way across Normandy. King John moved to Rouen with a much stronger force. He hoped to stop Lancaster. The English relieved and resupplied two besieged forts. Then they stormed and sacked the important town of Verneuil. John chased them, but he missed chances to fight the English. They escaped. In three weeks, the English gained much loot, including many horses. They damaged the French economy and reputation. New alliances were made. There were few English losses. The French King was distracted from the English plans for a bigger raid from southwest France.

Preparing for the Raid

The French announced a formal call to arms for all able-bodied men on May 14. The response was not good. The call was repeated in late May and early June. The French were so short of money that they could not pay the soldiers who did show up. The French army had weaknesses. It had thousands of small groups of soldiers. They were not used to working together. Their commanders did not know them. Their health, training, and equipment varied greatly. John's fifteen-year-old son, John, Count of Poitiers, was given command of an army in Languedoc. His job was to guard against the Black Prince repeating his raid from the year before.

The Black Prince received more soldiers. Edward ordered 600 more longbowmen to be raised in England just for Gascony. Horses, food, and supplies also arrived during the spring. Ralph, Earl of Stafford, arrived in mid-June 1356 with more soldiers and supplies. He also brought orders from Edward. The Black Prince called a big meeting of Gascon nobles and town leaders. He asked for their advice. When they agreed on war, he asked for money to fight it. Because of his recent successes, he was given a tax of one-fifteenth of all movable goods in Gascony. He thanked them and gave a speech. He encouraged many people to join the upcoming campaign.

The Anglo-Gascon army gathered at Bergerac. The town had good river links to Bordeaux for supplies. From there, the Prince could attack in several directions. The hope was that this would make the French divide their forces. In fact, there was already a plan. Three English armies would meet somewhere on the Loire River. Edward would march southwest from Calais. Lancaster would attack south from Brittany. The Black Prince would move north from Bergerac.

In Normandy, John's army started besieging Breteuil again on July 12. Breteuil was the last fort holding out against him in eastern Normandy. The royal army was praised for its splendor and the high rank of its many participants. However, it made little progress. Breteuil was well-guarded and had enough food for a year, supplied by Lancaster. John tried to dig tunnels under the walls, but it did not work.

The Great Raid

Marching North

So many Gascons arrived at Bergerac that there was a worry. The province might not be defended enough if the French attacked back. So, 2,000–3,000 men were left behind. They stayed under the Seneschal of Gascony, John de Cheverston. The army that set out had about 6,000 fighting men. This included 3,000 English and Gascon men-at-arms. There were 2,000 archers, mostly English and Welsh longbowmen. And 1,000 other infantry, mostly Gascons. They were joined by about 4,000 non-fighters. All the fighting men were mounted, even those who would fight on foot. On August 4, 1356, they headed north. On the 6th, they reached Périgueux, which they looted. On August 14, the army crossed the River Vienne. They stopped on the 15th at Lesterps to rest and fix equipment. They had marched 113 miles (182 km) from Bergerac.

The Anglo-Gascon army then split into three groups, called "battles." They moved north side-by-side. They began to systematically destroy the countryside. There would be about 40 miles (64 km) between the groups on the sides. This allowed them to destroy a band of French land more than 50 miles (80 km) wide. Yet, they could still unite to face an enemy in about a day. They moved slowly to help with looting and destruction. Historian David Green said the Black Prince's army was "deliberately destructive, extremely brutal... methodical and sophisticated." Several strong castles were attacked and captured. Most townspeople fled or surrendered quickly. Overall, there was little French resistance. No French army stopped the Prince's forces from spreading out to cause maximum damage.

The main French army stayed in Normandy. It was clear Breteuil could not be stormed or starved. But John felt he could not leave the siege. This would hurt his reputation as a warrior-king. He refused to march against the Black Prince. He said the Breteuil garrison was a more serious threat. In August, a very large mobile siege tower was pushed to Breteuil's walls. A big attack was launched. The defenders set fire to the tower and fought off the attack. Sumption said French losses in this attack were "terrible." He called the whole second siege "a pointless endeavor." Historian Kenneth Fowler called the siege "magnificent but archaic." Eventually, John had to give in to pressure. He had to do something to stop the destruction in southwest France. Around August 20, he offered the Breteuil garrison free passage to the Cotentin. This was a huge bribe. He also let them take their valuables. This convinced them to leave the town. The French army quickly marched south. All available forces were sent against the Black Prince.

The Anglo-Gascons had been moving towards Bourges. This was a large, well-fortified town. The Count of Poitiers had moved his army there. He was gathering French forces from the region. Poitiers retreated as the Anglo-Gascons advanced on Bourges. A part of the Black Prince's army tried and failed to take the town. Then they burned the suburbs and continued north. This group reached Aubigny, 30 miles (48 km) to the north, by August 28. It was looted and destroyed. Anglo-Gascon forces kept going north. They looked for a place to cross the Loire River. But it had been a wet summer. The river was too fast and deep to cross easily. The French had destroyed all bridges they could not defend. Also on the 28th, a large French scouting party was driven off near Aubigny. From prisoners, the Black Prince learned that the main French army was moving. It was approaching Orléans. John hoped to fight the Prince near Tours.

Fights Along the Loire

The Black Prince heard John was marching on Tours and ready to fight. He moved his three groups closer together. He ordered them to move towards Tours. He was willing to fight an open battle, if the conditions were right. He still hoped to cross the Loire. This would let him fight the French army. It would also let him link up with Edward's or Lancaster's armies, if they were nearby. On August 29, another group of French men-at-arms was ambushed. They were led by Boucicaut, the new marshal of France. Fresh English troops drove them off and chased them to Romorantin castle. The whole Anglo-Gascon army gathered here. They attacked the castle on the 30th. The outer walls were captured. But the French held out in the keep. A war council decided to besiege it. They hoped to capture Boucicaut. They also expected a battle if John tried to help the castle. But John was still gathering his forces at Orléans and Chartres. So the Anglo-Gascons could focus on attacking Romorantin. The French surrendered on September 3.

The French royal army from Breteuil had moved to Chartres. It received more soldiers there, especially men-at-arms. John sent almost all the foot soldiers home. He kept only mounted soldiers. This made his army as fast as the Black Prince's mounted army. Sending home many foot soldiers also saved money. John believed the poorly trained militia were not very useful. Still, he was criticized for this decision then and later. Two hundred Scottish chosen men-at-arms joined John at Chartres. They were led by William, Earl of Douglas. Once John felt he had a very strong force, he set off south towards the Loire. Then he moved southwest along its north bank.

The Anglo-Gascons marched west from Romorantin. They went along the Cher valley towards Tours. Scouts were sent north to find places to cross the Loire. But as before, they could not find shallow crossings or intact bridges that were not strongly guarded. The campfires of the French army were visible to the north. Early on September 8, the Black Prince's army reached Tours. He heard that Lancaster was not far to the east, across the Loire. Lancaster hoped to join him soon. The Anglo-Gascons prepared for battle. They expected the French to arrive any moment. But John had crossed the Loire at Blois, east of Tours, on September 10. There, he was joined by the Count of Poitiers' army.

Other English Attacks

Meanwhile, the expected help from England did not arrive. In early August, a fleet of galleys from Aragon arrived in the English Channel. Galleys were ships used in the Mediterranean. The French used them in northern waters during summer. They were shallow-draft ships powered by oars. This made them good for raiding and fighting other ships in close combat. The French had only nine galleys. But they caused panic among the English. Edward was still trying to raise an army for France. Ships were being gathered. The soldiers gathered were split up to guard the coast. The ships sailing to Southampton to carry the army were ordered to stay in port until the galleys left.

In August, Lancaster marched south from eastern Brittany. The size of his army is not known. He had brought 2,500 men from Normandy. He also had over 2,000 men guarding English forts in Brittany. It is not known how many of these garrison men he added to his troops before marching to help the Black Prince. Like the Black Prince, Lancaster could not cross the river. The river was unusually high, and the French controlled the bridges. In early September, he gave up trying to cross at Les Ponts-de-Cé. He returned to Brittany. On the way, he captured and guarded many French strongholds. Once back in Brittany, he began to besiege its capital, Rennes.

Battle Plans

The Anglo-Gascon army was balancing things carefully. When there were no large French forces, they spread out to loot and destroy. Their main goal was to use the threat of destruction to force the French army to attack them. The Anglo-Gascons were confident they could defeat a larger French force. They believed they could do this by fighting defensively on ground they chose. If the French were too many, they were also sure they could avoid battle by moving around.

The French knew this plan. They usually tried to trap English forces against a river or the sea. This way, the English would run out of food. Then they would be forced to attack the French in a prepared position. Once John crossed the Loire, he tried many times to put his army between the Anglo-Gascons and Gascony. This would force them to fight their way out. Meanwhile, the Black Prince did not want to retreat quickly to Gascony. He wanted to move near the French army. He hoped to make them attack on bad terms, without getting trapped himself. He knew John had been eager to fight Lancaster's army in Normandy in June. He expected this eagerness for battle to continue.

Retreating South

After crossing the Loire on September 10 and getting more soldiers, John moved to cut off the Anglo-Gascon retreat. Hearing this, and losing hope that Lancaster would join him, the Black Prince moved his army about 8 miles (13 km) south to Montbazon. He took up a new defensive position on September 12. On the same day, John's son and heir, Charles, the Dauphin, entered Tours. He had traveled from Normandy with 1,000 men-at-arms. Hélie de Talleyrand-Périgord, a Cardinal, arrived at the Black Prince's camp. He tried to arrange a two-day truce for Pope Innocent VI. Some sources say this was for peace talks. Others say it was for an arranged battle.

The Black Prince was happy to fight. But he worried that a two-day delay would leave his army with its back to the Loire. This area also had few supplies. So, the Black Prince sent Talleyrand away. He marched hard and crossed the River Creuse at La Haye on the 13th, 25 miles (40 km) to the south. John knew he had more soldiers than the Anglo-Gascons. He wanted to destroy them in battle. So he also ignored Talleyrand. The French army kept marching south, parallel to the English. They did not move directly towards them. Their goal was to cut off their retreat and supply lines. On the 14th, the English marched 15 miles (24 km) southwest to Châtellerault on the Vienne.

At Châtellerault, the Black Prince felt there were no natural barriers to trap his army. He believed he was in a good defensive spot. He arrived there on September 14. This was the day Talleyrand had suggested for the battle. He waited for the French to come to him. Two days later, his scouts reported that John had gone around his position. John was about to cross the Vienne at Chauvigny. At this point, the French had lost track of the Anglo-Gascon army. They did not know where it was. But they were about to accidentally place themselves 20 miles (32 km) south of the Anglo-Gascons. This was directly in their path back to friendly land. The Black Prince saw a chance to attack the French while they were marching. Maybe even while they were crossing the Vienne. So he set off at dawn on the 17th to stop them. He left his baggage train behind to follow as best it could.

When the Anglo-Gascon front line reached Chauvigny, most of the French army had already crossed. They had marched towards Poitiers. A group of 700 men-at-arms from the French rear guard was stopped near Savigny-Lévescault. Writers at the time said they were not wearing helmets. This suggests they were not fully armored and did not expect a fight. They were quickly defeated. 240 were killed or captured, including 3 counts. Many Anglo-Gascons chased the fleeing French. But the Black Prince held back most of his army. He did not want to scatter it so close to the enemy. He camped at Savigny-Lévescault. In response, John lined up his army outside Poitiers for battle.

The Battle of Poitiers

On September 18, the Anglo-Gascons marched towards Poitiers ready for battle. They hoped the French would attack right away. Instead, Talleyrand came to negotiate. The Black Prince at first did not want to delay the battle. He was convinced to talk after Talleyrand pointed out something important. The two armies were so close. If the French did not attack, the Anglo-Gascons would find it almost impossible to retreat. If they tried to retreat, the French would attack. They would try to defeat them bit by bit. If they stayed, they would run out of supplies before the French. Talleyrand did not know that the Anglo-Gascons were already struggling to find enough water for their horses.

After long talks, the Black Prince agreed to many things. He would get free passage to Gascony. But these agreements depended on his father, Edward III, approving them. The French did not know that Edward had given his son written permission. He could "help himself by making a truce or armistice, or in any other way that seems best to him." This makes modern historians doubt if the Prince was truly sincere. The French discussed these ideas for a long time. John was in favor. But several senior advisors felt it would be shameful. They felt they had the Anglo-Gascon army, which had destroyed so much of France, at their mercy. They did not want to just let it escape. John was persuaded. Talleyrand told the Black Prince that he should expect a battle.

Attempts to agree on a battle site failed. The French wanted the Anglo-Gascons to move from their strong defensive position. The English wanted to stay there. Early on September 19, Talleyrand tried again to arrange a truce. But the Black Prince refused. His army's supplies were already running out.

The English army was set up in three groups, side-by-side. There was also a small reserve. The French army had 14,000 to 16,000 men. 10,000–12,000 were men-at-arms. 2,000 were crossbowmen. 2,000 were foot soldiers not classed as men-at-arms. They were divided into four groups. The last group was held in reserve under the King. John ordered the French sacred flag, the oriflamme, to be raised. This meant no prisoners were to be taken, on pain of death. One writer at the time said John made one exception: for the Black Prince.

At first, neither side wanted to advance across the rough ground between the armies. So the Black Prince, needing to start a battle, moved his 6,000-strong army across the front of the French. He made them believe they could catch the Anglo-Gascons at a disadvantage.

Most of the French had gotten off their horses. They sent their horses to the back. But some of the French front line, who were mounted, attacked. They thought the movement meant the Anglo-Gascons were retreating. They were driven back. But the French front line, on foot, followed them. After a long fight, this group was also pushed back by the now-confident English. The second French group, with 4,000 men-at-arms under Charles, the Dauphin, then attacked. They were all on foot. They were also pushed back by the Anglo-Gascons. But this was even harder than the first group.

As the Dauphin's group fell back, there was confusion among the French. About half the men of their third group, under Philip, the Duke of Orléans, left the field. They took many survivors of the first two attacks and all four of John's sons with them. The remaining French gathered around the King. They launched a third attack against the tired Anglo-Gascons. Again, they were all foot soldiers.

The Black Prince worried his army would break and run. He ordered an advance. This boosted Anglo-Gascon morale and shook the French. Some Anglo-Gascon men-at-arms got on their horses and charged the French. The battle started again. The French were slowly gaining the upper hand. Then a small force of 160 men appeared behind the main French force. They had been sent earlier to threaten the French rear. Believing themselves surrounded, some French soldiers fled. This panicked others. Soon, the entire French force collapsed.

John was captured. So was the `oriflamme` flag. One of John's sons, Philip, was also captured. According to different sources, 2,000 to 3,000 men-at-arms were captured. About 2,500 French men-at-arms were killed. About 3,300 common soldiers were also killed. Modern sources estimate Anglo-Gascon deaths at about 40 men-at-arms. An unknown but much larger number of archers and other foot soldiers also died.

After the Battle

The French worried that the victorious Anglo-Gascons would try to storm Poitiers or other towns. Or that they would continue their destruction. The Black Prince was more concerned with getting his army, with its prisoners and loot, safely back to Gascony. He knew many French soldiers had survived the battle. But he did not know how organized or brave they were. The Anglo-Gascons moved 3 miles (4.8 km) south on September 20. They cared for the wounded, buried the dead, paroled some prisoners, and reorganized their groups. On September 21, the Anglo-Gascons continued their march south. They moved slowly, weighed down with loot, treasures, and prisoners. On October 2, they entered Libourne. They rested while a grand entrance was planned for Bordeaux. Two weeks later, the Black Prince escorted John into Bordeaux. There were very excited crowds.

What Happened Next

Rogers described the Black Prince's `chevauchée` as "the most important campaign of the Hundred Years' War." After it, English and Gascon forces raided widely across France. There was little or no opposition. With no strong central government, France fell into chaos. In March 1357, a truce was agreed for two years. In April, the Black Prince sailed for England. He was with his prisoner, King John. They landed at Plymouth on May 5.

By May 1358, long talks between John and Edward led to the First Treaty of London. This treaty would have ended the war. It involved a large transfer of French land to England. And a huge ransom for John's freedom. The land transfer was similar to the earlier, failed Treaty of Guînes. The French government was not keen on it. And they could not raise the first payment of John's ransom. So the treaty failed. A peasant revolt called the `jacquerie` broke out in northern France in the summer of 1358. It was brutally put down in June.

Eventually, John and Edward agreed to the Second Treaty of London. This was similar to the first. But even larger parts of French land would be given to the English. In May 1359, the Dauphin and the Estates General also rejected this.

In October 1359, Edward led another campaign in northern France. French forces did not oppose it. But the English army could not take any strongly fortified places. Instead, the English army spread out. For six months, they destroyed much of the region. Both countries found it almost impossible to pay for continued fighting. But neither wanted to change their minds about the peace terms. On April 13, 1360, near Chartres, the temperature dropped sharply. A heavy hail storm killed many English baggage horses and some soldiers. Edward took this as a sign from God. He reopened talks directly with the Dauphin. By May 8, the Treaty of Brétigny was agreed. This largely copied the First Treaty of London.

By the Treaty of Brétigny, huge areas of France were given to England. The Black Prince would rule them personally. John was ransomed for three million gold écu. Rogers states "Edward gained territories comprising a full third of France, to be held in full sovereignty, along with a huge ransom for the captive King John—his original war aims and much more." At the time, it seemed this was the end of the war. But large-scale fighting broke out again in 1369. Most of the lost land was recaptured. The Hundred Years' War did not end until 1453.

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |