Douglas Bader facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

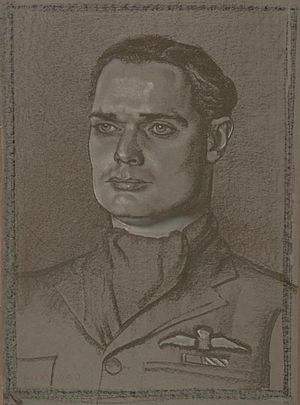

Sir Douglas Bader

|

|

|---|---|

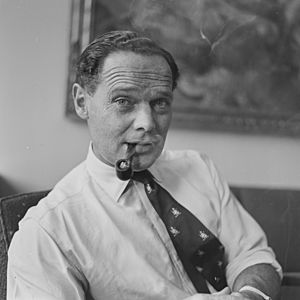

Douglas Bader in 1955

|

|

| Nickname(s) | Dogsbody |

| Born | 21 February 1910 St John's Wood, London |

| Died | 5 September 1982 (aged 72) Chiswick, London |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ |

Royal Air Force |

| Years of service | 1928–1933 1939–1946 |

| Rank | Group Captain |

| Service number | 26151 |

| Commands held | Tangmere Wing Duxford Wing No. 242 Squadron |

| Battles/wars | Second World War |

| Awards | Knight Bachelor Commander of the Order of the British Empire Distinguished Service Order & Bar Distinguished Flying Cross & Bar Mentioned in Despatches |

| Other work | Aviation consultant Disabled activist |

Group Captain Sir Douglas Robert Steuart Bader (born 21 February 1910 – died 5 September 1982) was a famous Royal Air Force flying ace during the Second World War. A flying ace is a pilot who shoots down five or more enemy aircraft. Douglas Bader was credited with shooting down 22 enemy planes. He also shared in four other victories and damaged many more.

Bader joined the RAF in 1928. In December 1931, he had a terrible accident while doing aerobatics (fancy flying stunts). His plane crashed, and he lost both of his legs. Even though he was very close to death, he recovered. He then trained to fly again and passed his tests. He asked to become a pilot once more. At first, the RAF said no because there were no rules for his situation. He was forced to retire from flying.

When the Second World War started in 1939, Douglas Bader was allowed to rejoin the RAF as a pilot. He achieved his first victories over Dunkirk during the Battle of France in 1940. He then fought in the famous Battle of Britain. He became a strong supporter of Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory and his "Big Wing" idea. This was a tactic to use large groups of fighter planes in battle.

In August 1941, Bader had to bail out of his plane over German-occupied France. He was captured by the Germans. Soon after, he met and became friends with Adolf Galland, a top German fighter ace. Even with his disability, Bader tried to escape many times. Because of this, he was sent to the prisoner-of-war camp at Colditz Castle. He stayed there until April 1945, when the camp was freed by the First United States Army.

Bader left the RAF for good in February 1946. He went back to working in the oil industry. In the 1950s, a book and a film called Reach for the Sky told the story of his life and RAF career. Bader also worked hard to help disabled people. In 1976, he was made a Knight Bachelor for his work. This meant he was called "Sir Douglas Bader." He kept flying planes until he became too unwell in 1979. Douglas Bader died on 5 September 1982, at the age of 72, after a heart attack.

Early Life

Childhood and School

Douglas Bader was born on 21 February 1910 in St John's Wood, London. He was the second son of Frederick Roberts Bader and Jessie Scott MacKenzie. For his first two years, he lived with relatives while his parents were in India.

When he was two, Bader joined his parents in India for a year. In 1913, his family moved back to London. His father fought in the First World War and was wounded. He died in 1922 from these injuries.

Bader's mother later remarried. Douglas grew up in the village of Sprotbrough, near Doncaster. He was a very energetic child. He found a good way to use his energy at St Edward's School. He was excellent at sports, especially rugby. He enjoyed playing against older and bigger students. The headmaster, Henry E. Kendall, understood Bader's competitive spirit. He even made him a prefect, which is like a student leader. Other famous RAF pilots, Guy Gibson and Adrian Warburton, also went to this school.

Bader loved sports even when he joined the military. He played for the Royal Air Force cricket team in important matches. He even played cricket in a German prisoner-of-war camp after he was captured in 1941.

In 1923, when Bader was 13, he saw an Avro 504 plane during a school holiday. He visited his aunt, who was marrying an RAF pilot at RAF Cranwell. He liked aviation, but he was more interested in sports. He didn't focus much on his schoolwork. However, with encouragement from his headmaster, he improved his studies. He was accepted as a cadet at RAF Cranwell, a special college for RAF officers. He also turned down a place at Oxford University because he preferred Cambridge.

His mother said she couldn't afford Cambridge. A teacher helped pay some of the fees. Bader then learned about special cadetships offered by RAF Cranwell. He was one of the top applicants and joined Cranwell in 1928, at age 18.

Joining the RAF

In 1928, Bader joined the Royal Air Force College Cranwell in Lincolnshire. He continued to be great at sports, adding hockey and boxing. He also loved motorcycling, even though some activities like speeding were not allowed. He was almost kicked out for breaking rules and for his poor exam results. But his commanding officer, Air vice-marshal Frederick Halahan, gave him a warning.

Bader had his first flight on 13 September 1928. He flew solo for the first time on 19 February 1929, after just over 11 hours of flying lessons.

On 26 July 1930, Bader became a pilot officer in No. 23 Squadron RAF at Kenley. He flew Gloster Gamecocks and later Bristol Bulldogs. Bader became known for doing risky and illegal stunts. The Bulldog plane was fast but hard to control at low speeds, making stunts very dangerous. Pilots were told not to do aerobatics below 2,000 feet. Bader often ignored this rule.

After one training flight, Bader didn't hit the target very well. To show off his skill, he took off to do aerobatics. This was against the rules, and many accidents from ignoring rules had been deadly. His commanding officers, Harry Day and Henry Wollett, gave pilots some freedom but also told them to know their limits.

No. 23 Squadron had won the "pairs" event at the Hendon Air Show in 1929 and 1930. In 1931, Bader and Harry Day won the title again. In late 1931, Bader trained for the 1932 Hendon Air Show. Two pilots had died trying aerobatics. Pilots were warned not to practice below 2,000 feet and to stay above 500 feet.

However, on 14 December 1931, Bader tried some low-flying aerobatics at Woodley Airfield near Reading. He was flying a Bulldog plane. His aircraft crashed when the tip of its left wing hit the ground. Bader was rushed to the hospital. There, a surgeon named J. Leonard Joyce had to amputate both of his legs. One leg was removed above the knee, and the other below the knee.

After a lot of painful effort, Bader recovered. He learned to drive a special car, play golf, and even dance. While recovering, he met Thelma Edwards, a waitress, and they fell in love.

Bader got a chance to prove he could still fly in June 1932. A high-ranking official arranged for him to fly an Avro 504. He flew it very well. A medical exam said he was fit for active service. But in April 1933, the RAF decided to change their mind. They said his situation wasn't covered by their rules. In May, Bader was officially retired from the RAF due to his injuries. He took an office job with an oil company. On 5 October 1933, he married Thelma Edwards.

Second World War

Return to the RAF

As tensions grew in Europe between 1937 and 1939, Bader kept asking the Air Ministry to let him rejoin the RAF. He was finally invited to a meeting in London. Bader was sad to learn that only "ground jobs" (non-flying roles) were being offered. It looked like he wouldn't be allowed to fly. But Air Vice-Marshal Halahan, who had been his commander at Cranwell, personally supported him. He asked the Central Flying School to test Bader's flying skills.

On 14 October 1939, Bader was asked to report for flight tests on 18 October. He didn't wait. He drove there the next morning and started refresher courses. Even though some officials didn't want him to get full flying status, his hard work paid off. Bader was medically cleared for operational flying by the end of November 1939. He was sent to the Central Flying School to practice on modern aircraft.

On 27 November, eight years after his accident, Bader flew solo again in an Avro Tutor. Once in the air, he couldn't resist turning the plane upside down at 600 feet! Bader then moved on to flying Fairey Battle and Miles Master planes. These were the last training steps before flying the famous Spitfires and Hurricanes.

The Phoney War

In January 1940, Bader was sent to No. 19 Squadron RAF at Duxford Aerodrome near Cambridge. At 29, he was older than most of the other pilots. His friend from Cranwell, Geoffrey Stephenson, was the commanding officer. Here, Bader saw a Spitfire for the first time. Some people thought Bader was a successful fighter pilot partly because he had no legs. Pilots often blacked out during sharp turns in combat due to blood rushing from their brains to their legs. Since Bader had no legs, he could stay conscious longer, which gave him an advantage.

Between February and May 1940, Bader practiced flying in formation and air tactics. He also flew patrols over ships at sea. Bader had different ideas about air combat than the RAF. He believed in using the sun and flying high to surprise the enemy. But the RAF's official rules said pilots should fly in a line and attack one by one. Even though he disagreed, Bader followed orders. His skill quickly led to him being promoted to section leader.

During this time, Bader crashed a Spitfire during takeoff. He had forgotten to change the propeller pitch. The plane sped down the runway at 80 mph before crashing. Bader had a head wound, but he got into another Spitfire for a second try. After the flight, he found it hard to walk. He realized his artificial legs had been bent from being forced under the rudder pedals during the crash. He thought that if he hadn't lost his legs before, he would have lost them then. Bader was then promoted to flight lieutenant and became a flight commander of No. 222 Squadron RAF.

Battle of France

Bader first experienced combat with No. 222 Squadron RAF at RAF Duxford. On 10 May, the German army invaded several European countries. The battles went badly for the Allied forces. Soon, they were evacuating from Dunkirk during the battle for the port. RAF squadrons were ordered to control the skies for the Royal Navy during Operation Dynamo.

While patrolling near Dunkirk on 1 June 1940, Bader saw a Messerschmitt Bf 109 flying in front of him. He thought the German pilot must be new because he didn't try to escape. It took more than one burst of gunfire to shoot the plane down. Bader was also credited with damaging a Messerschmitt Bf 110, even though he claimed five victories in that fight.

In the next patrol, Bader damaged a Heinkel He 111. On 4 June 1940, he almost crashed into a Dornier Do 17 while firing at its rear gunner. Soon after Bader joined 222 Squadron, it moved to RAF Kirton in Lindsey.

After flying missions over Dunkirk, Bader was given command of No. 242 Squadron RAF on 28 June 1940. This squadron, flying Hawker Hurricanes, was based at RAF Coltishall. It was mostly made up of Canadians who had lost many planes and pilots in the Battle of France. When Bader arrived, their spirits were low. At first, the pilots didn't like their new commander. But Bader's strong personality and determination soon won them over. He helped the squadron become an effective fighting unit again. No. 242 Squadron was ready for combat on 9 July 1940.

Battle of Britain

After the French campaign, the RAF got ready for the Battle of Britain. The German air force, the Luftwaffe, wanted to control the skies over Britain. If they succeeded, Germany planned to invade Britain. The battle officially started on 10 July 1940.

On 11 July, Bader got his first victory with his new squadron. The clouds were low, and it was misty. Bader was alone on patrol when he was told about an enemy plane flying north along the Norfolk coast.

Bader saw the plane, a Dornier Do 17, and got closer. Its rear gunner started firing. Bader kept attacking and fired two bursts into the bomber before it disappeared into the clouds. The Dornier crashed into the sea. This was later confirmed by the Royal Observer Corps. On 21 August, a similar event happened. Another Dornier crashed into the sea, and again, the Observer Corps confirmed it. No one survived.

Later that month, Bader shot down two more Messerschmitt Bf 110s. On 30 August 1940, No. 242 Squadron moved back to Duxford and was in the middle of heavy fighting. On this day, the squadron claimed 10 enemy aircraft, with Bader shooting down two Bf 110s. Other squadrons were also involved, so it was hard to know exactly which RAF units were responsible for all the damage. On 7 September, two more Bf 110s were shot down. But in the same fight, Bader's Hurricane was badly hit by a Messerschmitt Bf 109. Bader almost had to bail out, but he managed to control his plane. Other pilots saw one of Bader's targets crash.

On 7 September, Bader claimed two Bf 109s shot down, followed by a Junkers Ju 88. On 9 September, Bader claimed another Dornier. During the same mission, he attacked a He 111 but ran out of ammunition. He was so angry he thought about ramming it with his propeller, but he turned away. On 14 September, Bader was given the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his leadership in combat.

On 15 September, known as Battle of Britain Day, Bader damaged a Do 17 and a Ju 88. He also destroyed another Do 17 in the afternoon. Bader flew several missions that day, with intense air combat. The Dornier's gunner tried to bail out, but his parachute got caught on the plane's tail, and he died when the aircraft crashed into the Thames Estuary. Another Do 17 and a Ju 88 were claimed on 18 September. A Bf 109 was claimed on 27 September. Bader was officially recognized on 1 October 1940. On 24 September, he was promoted to flight lieutenant.

"Big Wing" Tactic

Douglas Bader was a friend and supporter of his commander, Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory. Bader strongly believed in the "Big Wing" idea, which caused a lot of discussion in the RAF during the battle. Bader openly criticized the cautious tactics used by Air Vice Marshal Keith Park. Park was supported by Fighter Command's overall commander, Sir Hugh Dowding. Bader argued for an aggressive plan to gather large groups of fighter planes north of London. These "Big Wings" would then attack the large German bomber formations as they flew over South East England.

As the battle went on, Bader often led a combined group of fighters, sometimes up to five squadrons, known as the "Duxford Wing". It was hard to measure how successful the Big Wing was. The large formations often took too long to get ready. They also claimed more victories than they actually achieved and often didn't help the busy 11 Group in time. This disagreement likely led to Park and Dowding being replaced.

It's not known if Mallory and Bader knew that the RAF's claims for the Big Wings were too high. But they certainly tried to use these claims to remove Park and Dowding from command and push for the Big Wing tactic. After the war, Bader said that he and Leigh-Mallory only wanted the Big Wing tactic used in 12 Group. They believed it was not practical for 11 Group because it was too close to the enemy and wouldn't have enough time to form up.

During the Battle of Britain, Bader flew three Hawker Hurricane planes. In the first, P3061, he shot down six enemy planes. In the second, he got one victory and damaged two others. In the third, V7467, he destroyed four more planes and damaged two by the end of September. This plane was lost in a training exercise on 1 September 1941.

On 12 December 1940, Bader was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for his service during the Battle of Britain. His unit, No. 242 Squadron, had claimed 62 air victories. Bader was officially recognized on 7 January 1941. By this time, he was an acting squadron leader.

Wing Leader

On 18 March 1941, Bader was promoted to acting wing commander. He became one of the first "wing leaders." He was based at RAF Tangmere and commanded 145, 610, and 616 Squadrons. Bader led his wing of Spitfires on missions over north-western Europe throughout the summer. These missions were called "Circus operations." They involved bombers and fighters and were designed to draw out German Luftwaffe fighter units. One special benefit for a wing leader was having their initials painted on their aircraft. So, "D-B" was painted on Bader's Spitfire. These letters led to his radio call-sign "Dogsbody".

In 1941, his wing received new Spitfire VBs. These planes had two 20mm cannons and four .303 machine guns. Bader, however, flew a Mk VA, which had eight .303 machine guns. He believed these guns were more effective against enemy fighters. He liked to get very close to the enemy, where he felt the smaller guns had a greater impact.

Bader's combat missions were mostly against Bf 109s over France and the Channel. On 7 May 1941, he shot down one Bf 109 and claimed another as a probable victory. The German planes were from Jagdgeschwader 26 (JG 26), led by German ace Adolf Galland. On that day, Galland claimed his 68th victory. Bader and Galland would meet again 94 days later. On 21 June 1941, Bader shot down a Bf 109E near Desvres. Two other pilots saw the Bf 109 crash and the German pilot bail out. On 25 June 1941, Bader shot down two more Bf 109Fs. He also shared in destroying another Bf 109F in the same action.

The next month was even better for Bader. On 2 July 1941, he received a bar to his DSO, meaning he got a second DSO. Later that day, he claimed one Bf 109 destroyed and another damaged. On 4 July, Bader fired at a Bf 109E, which slowed down so much he almost crashed into it. It was marked as a probable victory. On 6 July, another Bf 109 was shot down, and the pilot bailed out. This was seen by Pilot Officers Johnnie Johnson and Alan Smith, who was Bader's usual wingman.

On 9 July, Bader claimed one probable and one damaged enemy plane. On 10 July, Bader claimed a Bf 109 over Bethune. Later, he destroyed a Bf 109E near Calais. On 12 July, Bader shot down one Bf 109 and damaged three others. Bader was again officially recognized on 15 July. On 23 July, Bader claimed another Bf 109 damaged, even though two Bf 109s were destroyed in that action. Bader didn't see his Bf 109 crash, so he only claimed it as damaged.

Bader wanted to fly more missions in late 1941, but his Wing was tired. He was determined to increase his score. This made the other pilots in his wing almost rebellious. Trafford Leigh-Mallory, Bader's boss, allowed Bader to continue frequent missions over France. Bader had 20 victories, and the strain was showing on him. But Leigh-Mallory didn't want to upset his best pilot.

Last Combat

Between 24 March and 9 August 1941, Bader flew 62 fighter missions over France. On 9 August 1941, Bader was flying his Spitfire Mk VA W3185 "D-B" on a patrol over the French coast. He was looking for Messerschmitt Bf 109s. His trusted wingman, Alan Smith, couldn't fly that day because of a cold. This might have played a part in what happened next.

Just after Bader's group of four planes crossed the coast, they saw 12 Bf 109s flying below them. Bader dived on them too fast and too steeply to aim his guns. He barely avoided crashing into one. He leveled out at 24,000 feet and found he was alone, separated from his group. He was thinking about going home when he saw three pairs of Bf 109s in front of him. He dropped down and got close, then destroyed one with a short burst of fire. Bader was firing at a second Bf 109 when he noticed two planes on his left turning towards him. He decided to go home. However, he made the mistake of turning away from them. Bader believed he then had a mid-air collision with the second of the two Bf 109s that were flying straight ahead.

Bader's plane lost its fuselage, tail, and fin. He fell quickly, spinning slowly. He threw off the cockpit cover and released his harness. The air started to pull him out, but his artificial leg got stuck. He fell for some time before he opened his parachute. At that point, the strap holding his leg broke, and he was pulled free. A Bf 109 flew by about 50 yards away as he got closer to the ground.

Search for W3185

The search for Bader's Spitfire, W3185, helped find another famous pilot's plane. This was Wilhelm Balthasar, a German ace, who died on 3 July 1941 when his Bf 109F crashed in France. His plane was found in March 2004. Later, in summer 2004, another plane was found. It was a Bf 109F flown by Albert Schlager, who was reported missing during Bader's last fight on 9 August 1941. There was a brief hope when a Spitfire wreck was found with a helmet marked "DB." But it was later identified as a Spitfire IX, which Bader's plane was not.

Bader's actual aircraft was never found. It likely crashed near Blaringhem, France. A French witness saw the Spitfire break apart as it fell. He thought it was hit by anti-aircraft fire, but there was none in the area. There were no Spitfire remains found. This wasn't surprising because the plane broke up in the air. Historians were also confused because a book said Bader's leg was dug out of the wreckage, suggesting a crash site. But Bader's leg was actually found in an open field.

Prisoner of War

The Germans treated Bader with great respect. When he was captured, he was sent to a hospital in Saint-Omer. This was near where his father's grave was located. When he left the hospital, Colonel Adolf Galland and his pilots invited him to their airfield. They welcomed him as a friend. Bader was even invited to sit in the cockpit of Galland's personal Bf 109. Bader asked Galland if he could test the 109 by flying it around the airfield. Galland laughed and said no!

Bader had lost one of his artificial legs when he bailed out of his damaged plane. His right prosthetic leg got stuck, and he only escaped when the straps broke after he pulled his parachute cord. General Adolf Galland told the British about Bader's damaged leg. He offered them safe passage to drop off a replacement. Hermann Göring, a high-ranking German official, even approved the operation. The British responded on 19 August 1941 with the "Leg Operation." An RAF bomber was allowed to drop a new artificial leg by parachute to St Omer, a German air base.

The Germans were less happy when, after dropping the leg, the bombers continued to bomb a power station nearby. Galland said in an interview that the plane dropped the leg after bombing his airfield. Galland and Bader didn't meet again until mid-1945. At that time, Galland and other German pilots were prisoners of war at RAF Tangmere. According to another pilot, Bader personally arranged for Hans-Ulrich Rudel, who was also an amputee, to get an artificial leg.

Bader tried to escape from the hospital where he was recovering by tying sheets together. The "rope" wasn't long enough at first. With help from another patient, he used a sheet from a New Zealand pilot's bed. A French maid at the hospital tried to contact British agents to help Bader escape to Britain. She brought a letter from a local couple who promised to hide him. Their son would wait outside the hospital every night. Eventually, Bader escaped through a window. The plan worked at first. Bader walked to the safe house, even though he was wearing a British uniform. But another woman at the hospital betrayed the plan. He hid in the garden when a German car arrived, but he was found. Bader said the couple didn't know he was there. The couple and the French maid were sent to forced labor in Germany. The couple survived the war.

Over the next few years, Bader caused a lot of trouble for the Germans. He often did what RAF personnel called ""goon-baiting"," which meant annoying the guards. He felt it was his duty to cause as much trouble as possible, including many escape attempts. He tried to escape so many times that the Germans threatened to take away his artificial legs.

On 15 February 1942, Bader was a prisoner at the Warburg POW camp. He managed to send a secret letter describing the camp conditions as "bloody." He said German food was poor and asked for better nutrition in Red Cross parcels. He was very confident, believing the Allies were six months away from victory. He also asked the RAF to keep bombing.

In Warburg, a German officer named Rademacher liked to enforce harsh searches and long roll calls. He often ordered searches of the barracks and delayed roll calls in the freezing cold. Another officer, Lieutenant Hager, would hit prisoners with his rifle butt during searches or long roll calls. On 10 April 1942, Hager hit Bader's wooden foot with a rifle butt. Bader just laughed and insulted him. Both Bader and Hager were sent to the cells as punishment. On 17 April 1942, Bader scolded Hager for not saluting him, his superior in rank. The command punished Hager for not respecting rank, and both were put in cells again.

In August 1942, Bader escaped with Johnny Palmer and three others from Stalag Luft III B in Sagan. Unfortunately, a German Luftwaffe officer was in the area. He wanted to meet Bader, so he went to his room, but there was no answer. Soon, the alarm was raised, and Bader was recaptured a few days later. During the escape attempt, the Germans put out a poster of Bader and Palmer asking for information. It described Bader's disability and said he "walks well with stick." Twenty years later, Bader received a copy of the poster from a Belgian prisoner. Bader found it funny because he had never used a stick.

He was finally sent to the "escape-proof" Colditz Castle Oflag IV-C on 18 August 1942. He stayed at Colditz until 15 April 1945, when it was freed by the First United States Army.

After the War

Last Years in the RAF

After returning to Britain, Bader was given the honor of leading a victory flypast of 300 aircraft over London in June 1945. On 1 July, he was promoted to temporary wing commander. Soon after, Bader looked for a new role in the RAF. Air Marshal Richard Atcherley, a former pilot, was commanding the Central Fighter Establishment at Tangmere. He and Bader had been junior officers together. Bader was given the job of commanding officer of the Fighter Leader's School. He was promoted to wing commander on 1 December and soon after to temporary group captain.

However, the role of fighter aircraft had changed a lot. Bader spent most of his time teaching about ground attacks and working with ground forces. Also, Bader didn't get along with the newer generation of squadron leaders, who thought he was "out of date." In the end, Air Marshal James Robb offered Bader a role commanding the North Weald sector. Bader might have stayed in the RAF longer if his mentor Leigh-Mallory hadn't died in a plane crash in November 1944. But Bader's desire to stay in the RAF had lessened.

On 21 July 1946, Bader retired from the RAF with the rank of group captain. He took a job at Royal Dutch Shell.

Postwar Career

Bader thought about going into politics and becoming a Member of Parliament (MP). But he disliked how the main political parties used war veterans for their own goals. Instead, he decided to join Shell. His decision wasn't about money. He wanted to repay a debt because Shell had been willing to hire him at age 23 after his accident. Other companies offered him more money, but he chose Shell out of principle.

Joining Shell also meant he could keep flying. He traveled as an executive and could fly light aircraft. He spent most of his time abroad flying a company-owned Percival Proctor and later a Miles Gemini. In 1946, Bader went on a public relations mission for Shell around Europe and North Africa with United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) Lieutenant General James Doolittle.

Bader became the managing director of Shell Aircraft until he retired in 1969. In that year, he also worked as a technical advisor for the film Battle of Britain. Bader traveled to many countries, becoming internationally famous. He was a popular speaker about aviation. In 1975, he spoke at the funeral of Air Chief Marshal Keith Park.

Personality

When the film Reach for the Sky came out, people thought Bader was like the quiet and friendly actor Kenneth More, who played him. Bader knew that the film makers had removed all his habits from when he was flying, especially his frequent use of bad language. Bader once said, "they still think [I'm] the dashing chap Kenneth More was." The book Reach for the Sky did mention some of Bader's more difficult traits. The author said Bader was "a somewhat 'difficult' person." Still, Bader was seen as a hero by the public, who saw him as a leader of The Few in the Battle of Britain.

Pete Tunstall, who met Bader, remembered how strong his personality was. Tunstall said, "On first meeting Douglas Bader, one was forcibly struck by the power of his personality." Tunstall found it strange that people criticized Bader's overbearing personality. He felt they were judging a man who had lost both his legs but still flew wartime aircraft by normal standards.

Bader was never afraid to share his opinions, which sometimes caused controversy. He was a strong conservative. His firm views on topics like juvenile delinquency (young people committing crimes), capital punishment (the death penalty), and apartheid (racial segregation, which he supported) drew a lot of criticism. He also supported Rhodesia's white minority government. During the Suez Crisis, Bader was in New Zealand. Some African countries in the Commonwealth criticized the decision to get involved in Egypt. Bader replied that they could "bloody well climb back up their trees."

In November 1965, during a trip to South Africa, Bader said that if he had been in Rhodesia when it declared independence, he "would have had serious thoughts about changing my citizenship." Later, Bader also wrote the foreword to Hans-Ulrich Rudel's biography Stuka Pilot. Even when it was known that Rudel was a strong supporter of the Nazi Party, Bader said that knowing this beforehand would not have changed his mind about his contribution.

In the late 1960s, Bader was interviewed on television, and his comments caused controversy. He said he wanted to be Prime Minister and listed some controversial ideas:

- Stop sanctions on Rhodesia so talks could happen without pressure.

- Stop immigration into Britain immediately until the "situation had been examined."

- Bring back the death penalty for murder.

- Ban betting shops, saying, "They breed protection rackets. That's why we're getting like Chicago in the '20s".

Bader was known to be stubborn, direct, and sometimes rude when he shared his opinions. During a visit to Munich as a guest of Adolf Galland, he walked into a room full of former Luftwaffe pilots and said, "My God, I had no idea we left so many of you bastards alive." He also used this phrase to describe the Trades Union Congress during economic problems in the 1970s. Later, he suggested that Britons who supported the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament were a "rabble" and should be sent out of the country.

Personal Life

Bader's first wife, Thelma, got throat cancer in 1967. Knowing she might not survive, they spent as much time together as possible. Thelma was a smoker, and even though she stopped, it didn't save her. After a long illness, Thelma died on 24 January 1971, at age 64.

On 3 January 1973, Bader married Joan Murray. They lived in the village of Marlston, Berkshire. Joan was the daughter of a steel businessman. She loved riding horses and was part of the British Limbless Ex-Servicemen's Association. They first met at one of the association's events in 1960. She also helped groups that offered riding for disabled people.

Bader strongly supported people with disabilities. He showed everyone how someone with a disability could still succeed. In June 1976, Bader was knighted for his work helping disabled people.

He received other awards too. Bader remained interested in aviation. In 1977, he became a fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society. He also received a Doctorate of Science from Queen's University Belfast. Bader also worked as a consultant for a company called Aircraft Equipment International. Bader's health got worse in the 1970s, and he stopped flying completely. On 4 June 1979, Bader flew his Beech 95 Travelair for the last time. This plane had been given to him when he retired from Shell. He had flown for a total of 5,744 hours and 25 minutes. Bader's friend Adolf Galland also retired from flying soon after for the same reasons.

His work was tiring for a man without legs and with a worsening heart condition. On 5 September 1982, after a dinner honoring Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur "Bomber" Harris at the Guildhall, Bader died of a heart attack. He was being driven through Chiswick, west London, on his way home.

Many important people attended his funeral, including Adolf Galland. Galland and Bader had been friends for over 40 years since they first met in France. Even though Galland was on a business trip to California, he made sure to attend the memorial service for Bader in London.

Tributes

A biography of Bader by Paul Brickhill, Reach for the Sky, was published in 1954. About 172,000 copies were sold in just the first few months. The first print run of 300,000 quickly sold out, making it the best-selling hardback book in Britain after the war. Brickhill had originally offered Bader half of all the money from the book.

As sales grew, Bader worried about how much he would keep after taxes. He asked for a new written agreement. Brickhill agreed to pay him a one-time amount of £13,125. Most of this was for 'expenses' and was tax-free. Only a small part was for 'services' and was taxable. The tax office later said Bader didn't have to pay any tax on his earnings.

After a film director bought the rights to make a movie, Bader regretted the new deal he made with Brickhill. He was so upset that he refused to go to the movie premiere. He only saw the film eleven years later, on television. He never spoke to Brickhill again and never answered his letters. The feature film was released in 1956, starring Kenneth More as Bader. It was the top movie in Britain that year.

On the 60th anniversary of Bader's last combat flight, his widow Joan unveiled a statue at Goodwood. This was where he took off for his last mission. The 6-foot bronze statue was the first tribute of its kind. It was made by Kenneth Potts and ordered by the Earl of March.

The Douglas Bader Foundation was started in 1982 by his family and friends. Many of them were former RAF pilots who had flown with Bader during the Second World War. One of Bader's artificial legs is kept by the RAF Museum in their warehouse.

He was the subject of This Is Your Life in 1982. He was surprised by the host during a reception in London.

The Northbrook College Sussex campus at Shoreham Airport has a building named after him. Aeronautical and automotive engineering are taught there. His wife, Joan Murray, opened the building.

The Bader Way in Woodley, Reading, is named after Bader. Woodley Airfield is where Bader lost his legs in a flying accident in 1931.

The Bader Road in Poole, Dorset, is named after Bader.

Bader Walk (formerly Douglas Bader Walk) is in Birmingham.

Among other street names related to aircraft in Apley, Telford, Shropshire, is a Bader Close.

A pub at Martlesham Heath, Suffolk, is named after Bader.

RAF Coltishall, an old air force base, was sold in 2006 and later renamed Badersfield.

Heyford Park Free School in Upper Heyford is on the site of a former US Air Force airfield. It has honored Bader by naming one of its school houses after him. The tie stripe for Bader House is blue.

Bader Drive near Auckland International Airport in Auckland, New Zealand, was named in Bader's honor. Bader Intermediate School (for Year 7 and 8 students) is also near Bader Drive in Mangere, Auckland.

A film production company, Bader Media Entertainment CIC, is named after Bader. Its logo shows a pipe and a feather.

The Douglas Bader Rehabilitation Unit at Queen Mary's Hospital, Roehampton, London, is named after him. It is a famous center for fitting artificial limbs and helping amputees. Diana, Princess of Wales opened it in 1993.

In 2020, a special school named the Bader Academy after Douglas Bader opened in Doncaster. The Academy's logo features a plane and the motto "where dreams take flight."

Honours and Awards

- 1 October 1940 – Acting Squadron Leader Bader was given the Companion of the Distinguished Service Order.

- 7 January 1941 – Acting Squadron Leader Bader was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

- 15 July 1941 – Acting Wing Commander Bader was awarded a bar to the Distinguished Service Order, meaning he received it a second time.

- 9 September 1941 – Acting Wing Commander Bader was awarded a bar to the Distinguished Flying Cross, meaning he received it a second time, for his bravery in flying against the enemy.

- 2 January 1956 – Group Captain Bader was made a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire for his work helping disabled people.

- 12 June 1976 – Group Captain Bader was made a Knight Bachelor for his services to disabled people.

Combat Rules

Bader believed his success came from following three basic rules, which were also shared by the German ace Erich Hartmann:

- "If you had the height, you controlled the battle." (This means flying higher than the enemy gives you an advantage.)

- "If you came out of the sun, the enemy could not see you." (The sun would blind the enemy, making it hard for them to see you coming.)

- "If you held your fire until you were very close, you seldom missed." (Waiting until you are very near the enemy plane makes your shots more accurate.)

See also

In Spanish: Douglas Bader para niños

In Spanish: Douglas Bader para niños

- Gheorghe Bănciulescu, a Romanian pilot who flew with amputated feet.

- Alexey Maresyev, a Soviet Second World War fighter ace who flew with amputated legs.

- James MacLachlan, a British Second World War fighter ace with an amputated arm.

- Hans-Ulrich Rudel, a German pilot who continued flying after losing a leg.

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |