Scotland in the early modern period facts for kids

The early modern period in Scotland was a time of big changes, roughly from 1513 to the mid-1700s. It started after King James IV died and ended around the time of the last Jacobite rebellions. This era saw Scotland transform from a medieval kingdom into a key part of Great Britain.

During this period, Scotland went through major religious changes, known as the Scottish Reformation, which made the country mostly Protestant. Kings and queens like James V, Mary Queen of Scots, and James VI faced many challenges, including wars with England and internal conflicts.

In 1603, James VI of Scotland also became King of England, uniting the crowns. This meant the Scottish king now ruled both countries. Later, in 1707, Scotland and England officially joined to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. This union led to more stability and economic growth, but also caused some people to rebel, hoping to bring back the old Stuart royal family.

Scotland's geography, with its Highlands and Islands and Lowlands, played a big role in how society and the economy developed. The Lowlands saw more growth in farming and early industries. This era also brought changes to how people lived, learned, and created art and music.

Contents

Scotland's Rulers and Politics

The 1500s: Kings, Queens, and Reformation

King James V's Reign

After King James IV died in battle in 1513, his young son, James V, became king. For many years, others ruled for him because he was too young. In 1528, James V finally escaped from the people controlling him and took charge.

He worked to bring peace to the Highlands and Borders. He also kept Scotland's old alliance with France strong, marrying two French noblewomen. James V increased the royal money by taxing the church. He also spent a lot on building beautiful royal palaces. However, his reign ended with a big defeat against England in 1542, and he died shortly after. His only heir was a baby daughter, Mary.

The "Rough Wooing"

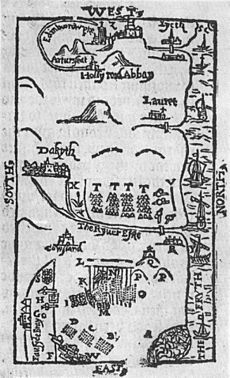

When Mary was a baby, England wanted her to marry their young prince, Edward. This would have united the two kingdoms. When the Scots refused, England invaded, trying to force the marriage. This period of fighting was called the "Rough Wooing."

In 1547, English forces won a major battle at Pinkie Cleugh. To protect Mary, the Scots sent her to France to marry the French prince. Her mother, Mary of Guise, stayed in Scotland to manage things. French troops came to help Scotland fight the English. Eventually, both English and French troops left Scotland after the Treaty of Edinburgh in 1560. This left Scotland free to make its own choices, especially about religion.

The Protestant Reformation

In the 1500s, Scotland experienced a huge religious change called the Scottish Reformation. This led to the creation of the national church, known as the Kirk, which became mostly Protestant and followed Calvinism.

Ideas from reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin spread in Scotland. English influence also played a part, with Protestant books and Bibles coming into the country. Important Scottish Protestants like Patrick Hamilton and George Wishart were executed for their beliefs. This only made more people support the new ideas.

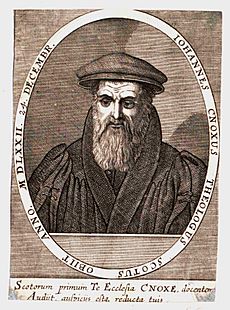

In 1560, with English help, a group of Protestant nobles called the Lords of the Congregation gained power. The Scottish Parliament then adopted a new faith, rejecting the Pope's authority. John Knox, who had been a galley slave and studied in Geneva, became the most important leader. The new church system, called Presbyterianism, gave more power to local leaders and removed many old church traditions. This led to the destruction of many church decorations and images. While many people were still Catholic, the Kirk slowly worked to convert the country, with less violence than in other parts of Europe.

Mary, Queen of Scots' Troubles

While the Reformation happened in Scotland, Queen Mary grew up in France as a Catholic. She married the French prince, who became King Francis II. When he died in 1560, Mary, at 19, returned to Scotland.

Even though she was Catholic, she didn't try to force her Protestant subjects to change their religion. However, her reign was full of problems. Her secretary, David Riccio, was murdered. Then, her unpopular second husband, Lord Darnley, was also murdered. Mary then married the Earl of Bothwell, who was suspected in Darnley's death.

The Scottish nobles were very unhappy. Mary was captured and forced to give up her crown to her baby son, James VI, in 1567. Mary later escaped and tried to win back her throne by force. But she was defeated at the Battle of Langside in 1568 and fled to England. In England, she became a focus for Catholic plots against Queen Elizabeth I. Mary was eventually executed in 1587.

King James VI's Rule

James VI became King of Scots when he was just 13 months old. He was raised as a Protestant, and Scotland was ruled by various regents until he was old enough. From 1584, James took more control. He brought peace among the powerful nobles and strengthened royal government.

In 1586, he signed a treaty with England. After his mother, Mary, was executed in 1587, James became the likely heir to the English throne, as Queen Elizabeth I had no children. He married Anne of Denmark in 1590, and they had children.

The 1600s: Union, Wars, and Restoration

Union of Crowns

In 1603, James VI of Scotland inherited the throne of England and Ireland. He moved to London, becoming James I of England. This was a "personal union," meaning the two countries shared the same king but remained separate kingdoms. James wanted to create a new "Great Britain."

He still kept a close eye on Scottish affairs, using letters and an efficient postal system. He controlled Scotland through the Privy Council of Scotland and the Scottish Parliament. He also increased the power of Scottish bishops. In 1618, he introduced the "Five Articles," which brought back some English church practices that were unpopular in Scotland. These changes caused a lot of anger.

King Charles I's Reign

In 1625, James VI died, and his son Charles I became king. Charles was born in Scotland but had lived in England most of his life. His first visit to Scotland was for his coronation in 1633.

Charles relied on a few Scottish advisors and bishops, which made many Scottish nobles unhappy. He also tried to take back lands that had been given away since 1542. This helped the church's money but angered the nobles who owned those lands. His religious policies also caused problems in England, leading him to rule without Parliament for many years.

The Bishops' Wars

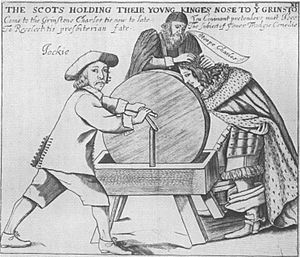

In 1635, Charles I tried to force a new prayer book and church rules on Scotland without asking the Scottish Parliament or church. This led to widespread anger and riots in 1637, famously started by Jenny Geddes throwing a stool in St Giles Cathedral.

Scottish nobles and ordinary people signed the National Covenant in 1638, opposing the King's changes. When Charles refused to compromise, the Scottish church removed all bishops and became fully Presbyterian.

The Scots formed an army led by Alexander Leslie, an experienced soldier. Charles also gathered an army, but it was not well-trained. After some small fights, both sides agreed to a temporary peace in 1639.

In 1640, Charles tried again to force his will, starting the Second Bishops' War. The Scots invaded England, taking control of Newcastle and other areas. This cut off London's coal supply. Charles was forced to agree to the Scots' demands and pay them a large sum of money. This made him call the English Parliament, which eventually led to the English Civil War.

Civil Wars in Scotland

As the English Civil War began, both King Charles and the English Parliament asked Scotland for help. The Scots, known as Covenanters, sided with Parliament in 1643, hoping to make England Presbyterian too. A Scottish army of 21,000 men crossed into England in 1644 and helped Parliament win a major victory at the Battle of Marston Moor.

In Scotland, James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose, led a campaign for the King in the Highlands. With help from Irish and Highland soldiers, he won several impressive victories against the Covenanters. However, his forces were eventually defeated at the Battle of Philiphaugh in 1645. King Charles I was defeated by Parliament's army and surrendered to the Scots in 1646.

The Scots tried to get Charles to agree to a Presbyterian church, but he refused. They eventually handed him over to the English Parliament. Relations between Scotland and the English Parliament worsened. In 1647, a group of Scots called the "Engagers" made a deal with the King to support him in a Second English Civil War if he would make England Presbyterian. However, the Engager army was defeated by Oliver Cromwell's forces at the Battle of Preston in 1648. Despite Scottish protests, King Charles I was executed in January 1649.

Occupation by the Commonwealth

After Charles I's execution, England became a "Commonwealth" (a republic). But in Scotland, his son was immediately proclaimed King Charles II. In 1650, Charles II came to Scotland and agreed to the Covenanters' demands.

England responded by sending an army under Oliver Cromwell into Scotland. Cromwell defeated the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar in 1650, taking many prisoners and occupying Edinburgh. Charles II was crowned in Scotland in 1651, and a new Scottish army was formed. However, this army was decisively defeated by Cromwell at the Battle of Worcester in 1651. Charles II escaped to Europe, and an English army occupied Scotland.

In 1652, the English Parliament declared Scotland part of the Commonwealth. Scotland was ruled by the English army, which brought law and order but largely suspended Scottish law. There was a Royalist uprising in the Highlands in 1653–55, but it was defeated.

The Monarchy Returns

After Cromwell died in 1658, General Monck, who was in charge of the English army in Scotland, marched south to London. He helped bring back the monarchy, and Charles II returned to the throne in 1660. This was known as the "Restoration."

Scotland got back its own laws, Parliament, and church. However, bishops were brought back into the church, which caused problems, especially in the south-west of Scotland where many people preferred the Presbyterian system. People who left the official church to worship in illegal outdoor meetings, called "conventicles," were persecuted.

In the 1680s, this persecution became very harsh, a time known as "the Killing Time." Many dissenters were executed or sent away.

King James VII is Deposed

Charles II died in 1685, and his brother, James VII of Scotland (and II of England), became king. James was openly Catholic. He put Catholics in important government jobs and tried to force religious tolerance for Roman Catholics, which angered his Protestant subjects.

In 1688, James had a male heir, meaning his Catholic policies would continue. Seven important Englishmen invited William of Orange (a Protestant and James's son-in-law) to invade England. James fled, leading to the "Glorious Revolution," which was almost bloodless.

In Scotland, William's supporters gained control. The Scottish Parliament declared that James had lost his right to the crown and offered it to William and Mary (James's daughter). They accepted, agreeing to limit royal power. Presbyterianism was brought back, and bishops were removed from the church.

However, many people in the Highlands still supported James. This group was called the Jacobites. They led several uprisings. The first was in 1689, led by John Graham, 1st Viscount Dundee, who won a battle but was killed. Without him, the Jacobite army was soon defeated.

Economic Problems and Overseas Colonies

The late 1600s saw hard economic times in Scotland. Trade slowed down, and there were four years of failed harvests (1695, 1696, 1698–99), known as the "seven ill years." This caused severe famine and a drop in population, especially in the north.

To help the economy, the Scottish Parliament set up the Bank of Scotland in 1695. They also created the "Company of Scotland" to raise money for trade and colonies overseas.

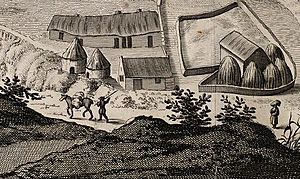

The company invested in the Darien scheme, an ambitious plan by William Paterson (who founded the Bank of England) to build a colony on the Isthmus of Panama. The idea was to create a trade route to Asia. Many Scots, from nobles to ordinary people, invested their money, hoping to boost Scotland's economy.

However, the English government and the English East India Company opposed the plan. Spain also claimed the land. English investors pulled out. Three fleets with 3,000 men sailed to Panama in 1698. The colony was a disaster. The colonists faced disease, constant rain, attacks from the Spanish, and no help from the English in the Caribbean. They abandoned the project in 1700. Only 1,000 survived, and only one ship returned to Scotland. The scheme cost Scotland a huge amount of money and caused widespread anger against England. This failure made many, including King William, believe that a full political union with England was necessary.

The 1700s: Union and Rebellions

Union with England

After King William died in 1702, Queen Anne (Mary's sister) became ruler. She had no surviving children, which meant the Protestant line of succession was uncertain. The English Parliament passed a law to ensure a Protestant heir. The Scottish Parliament, however, only said a Catholic could not be king, leaving open the chance that Scotland and England might have different monarchs.

To prevent this, the English Parliament pushed for a full union. They passed a law threatening to restrict Scots' property rights in England if union talks didn't happen. This would have hurt Scotland's trade. A political union also offered Scotland access to England's much larger markets and its growing empire.

Despite widespread opposition in Scotland, the Scottish Parliament voted to accept the Treaty of Union on January 6, 1707. This treaty confirmed the Protestant succession. The Church of Scotland and Scottish law remained separate. The English and Scottish parliaments were replaced by a single Parliament of Great Britain in Westminster. Scotland gained 45 members in the House of Commons and 16 in the House of Lords. It was also a full economic union, combining currency, taxes, and trade laws.

Jacobite Rebellions

The union with England was unpopular with many Scots, which revived the Jacobite cause. In 1708, James Francis Edward Stuart, known as "The Old Pretender" (son of James VII), tried to invade with French help, but the Royal Navy stopped him.

A more serious rebellion, called "The 'Fifteen," happened in 1715 after Queen Anne died and the first Hanoverian king, George I of Great Britain, took the throne. In Scotland, the Earl of Mar led the Jacobite clans, but he was not a strong leader. His army was defeated at the Battle of Sheriffmuir. James (the Old Pretender) arrived late and soon fled back to France. Another attempt with Spanish help in 1719 also failed.

In 1745, the last major Jacobite rebellion, "The 'Forty-Five," began. Charles Edward Stuart, "Bonnie Prince Charlie" or the "Young Pretender" (son of the Old Pretender), landed in Scotland. He had early success, taking Edinburgh and winning the Battle of Prestonpans. The Jacobite army marched into England, reaching Derby. However, they realized they wouldn't get much support in England and retreated to Scotland.

Charles's position weakened. He was pursued by the Duke of Cumberland's army and finally defeated at the Battle of Culloden on April 16, 1746. This crushed the Jacobite cause. Charles hid in Scotland before escaping to France. There were harsh punishments for his supporters. The Jacobite cause ended when the Young Pretender died in 1788 without children, and his brother, Henry, died in 1807.

Scotland's Geography

Scotland's geography is defined by the difference between the Highlands and Islands in the north and west, and the Lowlands in the south and east. The Highlands are very mountainous, while the Lowlands have more fertile land.

The Central Lowlands, about 50 miles wide, had the best farmland and easier travel, so most towns and government activities were there. The Southern Uplands and Highlands were less productive and harder to govern. The early modern period also saw the "Little Ice Age," with very cold winters and poor harvests, especially in the 1690s.

Roads improved in the Lowlands, making trade easier. In the Highlands, military roads were built in the 1700s to help troops move around. Scotland's borders were set by the early 1500s. After James VI became King of England in 1603, the border became less important for defense but remained a customs boundary until the 1707 Union.

Society in Early Modern Scotland

Social Classes

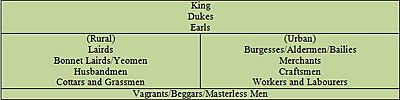

Below the king were a few dukes and earls, who were the highest nobles. Under them were the barons, who started to mix with local landowners, becoming known as lairds. Lairds were similar to gentlemen in England.

Below the lairds were groups like "bonnet lairds," who owned a lot of land. The number of people who owned land that could be passed down to their children grew. These landowners, called heritors, increasingly took on the responsibilities of local government.

Most of the working population were farmers and tenants. Serfdom (where people were tied to the land) had ended, but miners and saltworkers were almost like serfs by law. Landlords still had a lot of control over their tenants through local courts and church meetings.

In towns, wealthy merchants were at the top, often holding local offices. Below them were craftsmen and workers. At the very bottom were the unemployed and homeless, whose numbers grew during hard times.

Family and Clans

Unlike in England, where family ties came from both parents, in Scotland, kinship was mainly through the father's side. Women kept their own surnames after marriage. Marriages were often used to create friendships between family groups. Sharing a surname often meant you were part of a large family group that could support each other.

In the Borders, this led to feuds, where families sought revenge for wrongs done to their relatives. However, by the early 1700s, the government had largely stopped these feuds. The power of family heads in the Borders was replaced by that of landowning lairds.

In the Highlands, this system of kinship and loyalty created the clan system. The clan chief was usually the oldest son of the most powerful family branch. Leading families in the clan were like lowland lairds, giving advice and leading in war. Below them were tacksmen, who managed clan lands and collected rents. Most clan followers were tenants who worked for the clan leaders and sometimes fought as soldiers. They often took the clan name as their surname.

The clan system was not a threat to the government until after the Glorious Revolution. Economic changes and royal justice began to weaken the clan system before the 1700s. After the 1745 rebellion, the government sped up this process by banning Highland dress, disarming clansmen, and forcing chiefs to sell their traditional powers. Many ordinary clansmen were sent to colonies as indentured workers. This quickly turned clan leaders into simple landowners.

Population Changes

It's hard to know Scotland's exact population before the late 1600s. Estimates suggest that after the Black Death in the Middle Ages, the population might have dropped to half a million. Prices suggest the population grew in the early 1500s but leveled off after a famine in 1595.

By 1691, the population was estimated at 1.2 million. However, the famines of the 1690s likely reduced this number. The first reliable census in 1755 showed Scotland had about 1.26 million people.

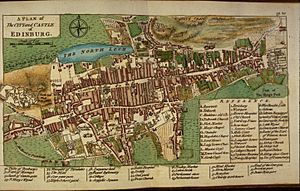

Compared to later times, the population was spread more evenly across the country, with about half living north of the River Tay. About 10% of people lived in towns, mostly in the east and south. Most towns had about 2,000 people, but Edinburgh was much larger, with over 10,000 people at the start of the era and 57,000 by 1750. Other large towns by the end of the period were Glasgow (32,000), Aberdeen (16,000), and Dundee (12,000).

Witch Trials

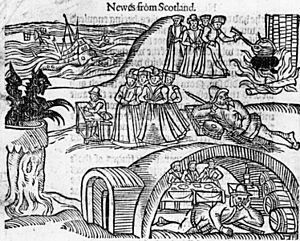

In late medieval Scotland, there were some cases of people being accused of witchcraft. After the Reformation, Parliament passed the Witchcraft Act 1563, making witchcraft a crime punishable by death. Scotland, with a quarter of England's population, had three times as many witchcraft trials, about 6,000 in total.

King James VI became very interested in witchcraft after visiting Denmark. He attended the North Berwick witch trials, where people were accused of using witchcraft to send storms against his ship. In 1597, James wrote a book called Daemonologie, which was against witchcraft.

In the 1600s, the Kirk (Church of Scotland) largely took over the hunt for witches. Witchcraft accusations were often used to stop superstitious and Catholic practices. Most of the accused (75%) were women. The most intense witch hunt was in 1661–62, with 664 named witches. After this, trials began to decline as judges and the government took more control. People also became more skeptical. The last recorded executions were in 1706, and the last trial was in 1727. The British Parliament repealed the Witchcraft Act in 1736.

Poverty and Homelessness

As the population grew and the economy changed from the mid-1500s, there was a growing problem of homelessness. The government passed laws in 1574, 1579, and 1592 to deal with this. The church became a key part of helping the poor, and local officials were given responsibility for the issue.

The 1574 law was similar to an English one. It only gave help to the "deserving poor" (the old, sick, and weak) and harshly punished "masterful beggars" (like jugglers and unlicensed tutors). Local church deacons or overseers made lists of the deserving poor. Those who didn't belong to the parish were sent back to their birthplace and could be punished. This law didn't try to provide work for able-bodied poor. In very hard times, the rules against begging were often ignored.

This legislation formed the basis of Scotland's "Old Poor Law," which lasted until the mid-1800s. Later laws continued to focus on helping the local deserving poor and punishing mobile beggars. The 1649 act said that local landowners should be taxed by the church to provide money for relief, rather than relying on donations. This system generally managed poverty and small crises but was overwhelmed during the major famines of the 1690s.

Warfare and Military Changes

In the early modern period, Scottish armies were made up of common people, feudal soldiers, and paid fighters. By the mid-1500s, it became harder to recruit soldiers. Soldiers usually brought their own equipment. Heavy armor was no longer used after the Battle of Flodden. Highland soldiers often wore lighter chainmail and their traditional plaid. Weapons included axes, pole arms, bows, and two-handed swords.

Gunpowder weapons became more common, replacing bows and spears. James IV brought experts from Europe to build guns and set up a gun foundry in 1511. Gunpowder changed how castles were built, making them stronger against cannons.

Scotland also tried to create a royal navy. James IV built a harbor at Newhaven and a dockyard. He acquired 38 ships, including the Great Michael, which was the largest ship in Europe at the time. These ships fought privateers and helped in expeditions. However, most were sold after James IV's death. Later, Scotland relied on private ships and hired merchant ships for naval efforts.

In the early 1600s, many Scots served in foreign armies during the Thirty Years' War. When the Bishops' Wars began, many experienced Scottish soldiers returned home and helped train the Covenanter armies. Scottish infantry usually used pikes and firearms. Cavalry often had pistols and swords.

During the English Civil Wars, Royalist armies in Scotland mostly had infantry with pikes and firearms. They often lacked heavy cannons and had few cavalry. The English tried to blockade Scotland by sea. After the Covenanters allied with the English Parliament, they set up patrol squadrons. However, the Scottish navy could not stop Cromwell's English fleet, which conquered Scotland in 1649–51. Scottish ships were then taken by the English Commonwealth fleet. During the English occupation, new fortresses were built in Scotland.

After the monarchy returned in 1660, Scotland created a standing army. This army was mainly used to stop Covenanter rebellions. Pikes became less important, replaced by muskets with bayonets. By the Glorious Revolution, Scotland's standing army had about 3,000 men.

After the Glorious Revolution, Scottish soldiers joined King William's wars in Europe. Scottish sailors also served in the Royal Navy. In the late 1600s, Scottish merchants also built a small fleet for the Darien Scheme and for protecting trade. After the Act of Union in 1707, these ships joined the Royal Navy.

By the time of the Union, Scotland had a standing army of several infantry and cavalry units. As part of the British Army, Scottish regiments fought in major European wars. The first official Highland regiment, the Black Watch, was formed in 1740. Jacobite armies were mostly made up of Highlanders serving in clan regiments. The clan gentlemen fought in the front ranks and were more heavily armed than the common clansmen.

Culture and Learning

Education in Scotland

Protestant reformers wanted more people to be educated. In 1560, a plan was made for a school in every parish, but this was too expensive. In towns, old schools became reformed grammar schools. Schools were supported by church money, local landowners, and parents who could pay. Church leaders inspected schools to check teaching quality and religious beliefs.

There were also many unofficial "adventure schools" that met local needs. Teachers often had other jobs, like working for the church. The best schools taught religious lessons, Latin, French, classical literature, and sports.

In 1616, a law ordered every parish to have a school "where convenient means may be had." The Scottish Parliament made this law stronger in 1633, introducing a tax on landowners to fund schools. A loophole was closed in 1646, creating a strong foundation for schools. Even though the monarchy's return in 1660 changed things back for a while, new laws in 1696 restored the 1646 provisions.

By the late 1600s, most Lowland parishes had schools. In the Highlands, education was still lacking due to distance and the fact that most people spoke Gaelic, which few teachers understood. The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, founded in 1709, helped by teaching English and trying to reduce Roman Catholicism. While some schools eventually taught the Bible in Gaelic, the overall effect was a decline in Highland culture.

After the Reformation, Scotland's universities were reformed by Andrew Melville in the late 1500s. He introduced new teaching methods, focusing on logic, languages, and sciences. He made Greek compulsory and encouraged the study of other ancient languages. This revitalized Scottish universities, making them as good as any in Europe.

After the political troubles of the 1600s, universities recovered. They offered a high-quality education to the sons of nobles and gentry, including economics and science. They became important centers for medical education and led the way in Enlightenment thinking. Key figures before the mid-1700s included Francis Hutcheson, a professor of moral philosophy, and Colin Maclaurin, a leading mathematician. David Hume (1711–76) was a very important thinker whose works helped shape modern philosophy.

Language in Scotland

By the early modern period, Gaelic was spoken mostly in the Highlands and Islands and was seen as a less important language. Middle Scots, which came from Old English with Gaelic and French influences, became the language of the nobility and most people. It was similar to the language spoken in northern England but had its own writing style.

From the mid-1500s, written Scots was increasingly influenced by the English language from Southern England. With more English books available, most writing in Scotland started to follow English styles. King James VI, who once praised Scots poetry, favored English after he became King of England in 1603. In 1611, the Scottish church adopted the King James Version of the Bible, which was in English. This led to English becoming the main language, with Gaelic at the bottom.

After the Union in 1707, many in power discouraged the use of Scots. Leading Scots like David Hume tried to speak standard English. Many wealthy Scots learned English from teachers like Thomas Sheridan. However, Scots remained the everyday language for many people in rural areas and the growing working class in towns.

Scottish Literature

King James V supported poets and writers. Sir David Lindsay was a very active poet who wrote a play called The Thrie Estaitis. James also attracted international writers to his court.

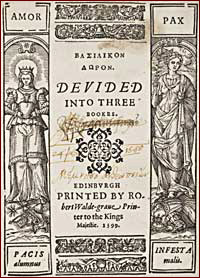

In the 1580s and 1590s, James VI promoted Scottish literature. He wrote a book called Some Rules and Cautions to be Observed and Eschewed in Scottish Prosody in 1584, which was a guide to Scottish poetry. He also supported a group of Scottish court poets and musicians called the Castalian Band. However, when he became King of England in 1603, he started to favor English, and Scottish literary traditions became less important.

This period also saw the rise of the ballad as a written form in Scotland. Some ballads might be very old, but they were mostly passed down by word of mouth until they were written down later. From the 1600s, noble writers also used ballads. Allan Ramsay (1686–1758) helped revive interest in older Scottish literature and developed a poetic form called the Habbie stanza.

Music in Scotland

Robert Carver (c. 1488–1558) was a famous Scottish composer in the early 1500s. His complex music was performed by large, trained choirs. King James V also supported musicians and played the lute. He brought French music to his court.

The Reformation greatly affected church music. Song schools closed, choirs were disbanded, and organs were removed from churches. The new Protestant church focused on singing Psalms. The Scottish Psalter of 1564 provided tunes for the psalms. Since everyone in the congregation now sang, the music became simpler.

When Mary returned from France in 1561, her Catholic faith brought new life to the Scottish Chapel Royal choir. However, without church organs, other instruments like trumpets, drums, and bagpipes were used. Mary herself played the lute and harpsichord and was a good singer.

James VI was a big supporter of the arts. He tried to revive town song schools. He rebuilt the Chapel Royal at Stirling in 1594. When he moved to England in 1603, Scotland lost a major source of royal music support.

Secular popular music continued despite the church's efforts to stop dancing and events like "penny weddings." Many musicians, like the fiddler Pattie Birnie and the piper Habbie Simpson, continued to perform. In the Highlands, piping families developed. The fiddle also became popular. After 1715, the church's strictness eased, and many music publications appeared. Italian classical music also came to Scotland, influencing Scottish songs and even the first Scottish opera.

Architecture in Scotland

King James V was influenced by French Renaissance building styles during his visits to France. His palaces, like Linlithgow, Holyrood, and Stirling, were some of the best examples of Renaissance architecture in Britain. Scottish architects often blended these European styles with traditional Scottish designs and materials like stone.

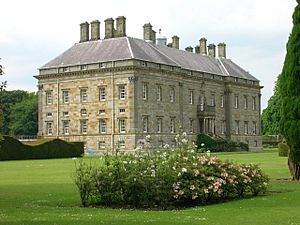

Buildings from James VI's reign continued to show Renaissance influences. Private houses of nobles also adopted these styles. The unique style of great private houses in Scotland, later called Scots baronial, began in the 1560s. It kept features of medieval castles, like high walls and corner towers, but with larger floor plans. William Wallace, the king's master mason, was very influential, blending Scottish and Flemish styles. This style was popular until the late 1600s.

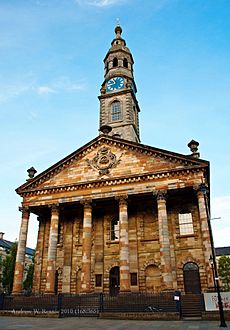

Calvinists rejected ornate church buildings, leading to the destruction of many medieval church decorations. New churches were built to focus on the pulpit and preaching. Many early churches were simple rectangles. A common design was the "T"-shaped plan, which allowed more people to be close to the pulpit. In the 1600s, some churches used a Greek cross plan, like Cawdor (1619).

During the civil wars, most building was for military purposes. After the Restoration, large-scale building began again, with a focus on classical styles. Sir William Bruce introduced the Palladian style to Scotland, building and remodeling country houses like Kinross House. He also rebuilt Holyroodhouse. James Smith also worked on many country houses in a plain but handsome Palladian style. After the Act of Union, Scotland's growing wealth led to many new public and private buildings. William Adam was the leading architect of his time, designing many country houses and public buildings in an energetic style that combined Palladian and Baroque elements.

Art in Scotland

Royal art in the 1500s was rich with stone carvings, wall paintings, and tapestries. At Stirling Castle, carvings on the royal palace included contemporary, biblical, and classical figures. However, the Reformation's destruction of church art meant the loss of most medieval stained glass, sculptures, and religious paintings.

This loss of church support forced artists to find new patrons. One result was the rise of Scottish Renaissance painted ceilings and walls. Many private houses of townspeople, lairds, and lords had detailed and colorful patterns and scenes. Over a hundred examples still exist, like the ceiling at Aberdour Castle. These were done by Scottish artists using European pattern books, often including symbols from humanism, heraldry, and classical myths.

Royal portrait painting was disrupted in the 1500s but grew after the Reformation. Anonymous portraits of important people exist. James VI hired Flemish artists, Arnold Bronckorst and Adrian Vanson, who painted the king and court figures. The first important native artist was George Jamesone (1589/90-1644), who became a successful portrait painter and trained the Baroque artist John Michael Wright. In the early 1700s, many painters were still artisans, like the Norie family, who painted Scottish landscapes for noble houses.

Economy and Trade

At the start of this period, Scotland's difficult terrain and poor roads meant there was little trade between different areas. Most communities relied on local produce, with little extra for bad years. Farming was based on small settlements where families jointly farmed land.

In the mid-1500s, demand for Scottish cloth and wool exports to Europe declined. Scots responded by selling more traditional goods like salt, herring, and coal. The late 1500s were economically tough, made worse by rising taxes and currency devaluation. Wages rose, but not as fast as prices. There were frequent harvest failures, leading to food shortages, and outbreaks of plague.

Some early industries began, often with European experts. For example, George Bruce used German methods to solve drainage problems in his coal mine. In 1596, the Society of Brewers was set up in Edinburgh, leading to Scottish beer production.

Famines were common in the early 1600s. The invasions of the 1640s severely damaged the Scottish economy, causing rapid price increases. Under the English Commonwealth, Scotland was highly taxed but gained access to English markets.

After the Restoration in 1660, the border with England and its customs duties were brought back. Economic conditions were generally good from 1660 to 1688. Landowners improved farming and cattle raising. The monopoly of royal towns over foreign trade was partially ended in 1672, opening up trade in goods like salt, coal, and hides, and imports from the Americas.

The English Navigation Acts limited Scotland's trade with English colonies, but Scots often found ways around them. Glasgow became an important trading center, importing sugar from the West Indies and tobacco from Virginia. Exports included linen, wool, coal, and grindstones. English tariffs on salt and cattle were harder to avoid. However, by the end of the century, drover's roads, used to move cattle from the Highlands to England, were well established.

The famines of the 1690s were very severe, partly because famines had become rare in the late 1600s. These shortages were the last of their kind.

After the union in 1707, Scotland began to experience economic growth. Contact with England led to efforts to improve agriculture. New farming methods were introduced, like haymaking, English plows, and new crops like turnips and cabbages. Lands were enclosed, marshes drained, and roads built. The introduction of the potato in 1739 greatly improved the diet of poor farmers.

The Society of Improvers was founded in 1723, with many nobles and landowners as members. The Lothians became a major grain area, Ayrshire for cattle, and the Borders for sheep. However, enclosures often led to unemployment and forced people to move to towns or abroad.

The biggest change in international trade was the rapid growth of the Americas as a market. Glasgow supplied the colonies with cloth, iron tools, glass, and leather goods. By 1736, Glasgow had many of its own ships trading with the New World. Glasgow became the center of the tobacco trade, re-exporting it to France. The wealthy merchants in this business were called the tobacco lords.

Other towns also benefited. Greenock expanded its port and became important in importing sugar and rum. Linen manufacturing was very important, especially in the Lowlands. The trade expanded significantly after 1727, with subsidies. Paisley became a major production center. Glasgow's export trade doubled between 1725 and 1738.

Banking also developed. The Bank of Scotland was founded in 1695, and the rival Royal Bank of Scotland in 1727. Local banks were also set up in towns like Glasgow. These banks provided money for businesses and for improving roads and trade.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Escocia en la Edad Moderna para niños

In Spanish: Escocia en la Edad Moderna para niños