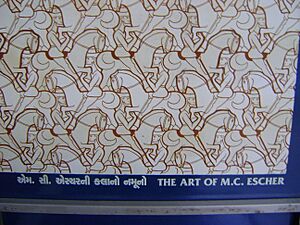

M. C. Escher facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

M. C. Escher

|

|

|---|---|

In November 1971

|

|

| Born |

Maurits Cornelis Escher

17 June 1898 Leeuwarden, Netherlands

|

| Died | 27 March 1972 (aged 73) Hilversum, Netherlands

|

| Resting place | Baarn, Netherlands |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Education |

|

| Known for | Drawing, printmaking |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Spouse(s) |

Jetta Umiker

(m. 1924) |

| Awards | Knight (1955) and Officer (1967) of the Order of Orange-Nassau |

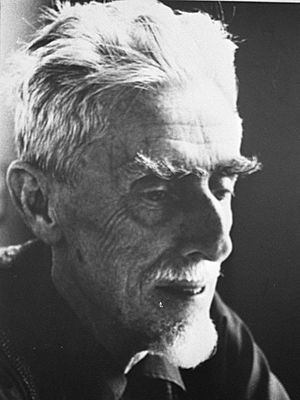

Maurits Cornelis Escher (born June 17, 1898 – died March 27, 1972), often called M. C. Escher, was a Dutch graphic artist. He was born in Leeuwarden, Netherlands.

Escher is famous for his art that often looks like it's inspired by math. He made woodcuts, lithographs, and mezzotints. His artworks often show impossible buildings, endless spaces, and patterns that fit together perfectly like tiles.

During his life, Escher created 448 lithographs, woodcuts, and wood engravings. He also made over 2000 drawings and sketches. Besides his famous prints, he illustrated books, designed tapestries, postage stamps, and murals.

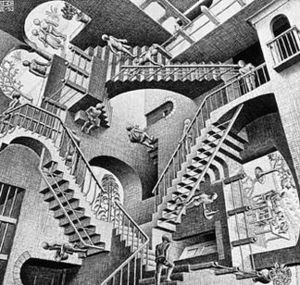

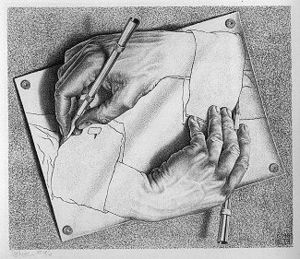

Escher was very interested in different art techniques. He often used patterns that repeated like tiles in many of his pieces. Early in his career, he found inspiration in nature. He studied art, landscapes, and insects. Some of Escher’s most well-known drawings include Drawing Hands, Relativity, and Flying Fish. Most of his works were connected to math.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Maurits Cornelis Escher was born on June 17, 1898. He was born in Leeuwarden, Friesland, in the Netherlands. His birth house is now part of the Princessehof Ceramics Museum. He was the youngest son of George Arnold Escher, a civil engineer, and his second wife, Sara Gleichman.

In 1903, Escher's family moved to Arnhem. He went to primary and secondary school there until 1918. His friends and family called him "Mauk." He was often sick as a child and went to a special school at age seven. He even failed the second grade. Even though he was very good at drawing, his other grades were usually poor. He took carpentry and piano lessons until he was thirteen.

In 1918, he went to the Technical College of Delft. From 1919 to 1922, Escher studied at the Haarlem School of Architecture and Decorative Arts. He learned drawing and how to make woodcuts. He first studied architecture, but he struggled with some subjects. This was partly because of a skin infection. So, he switched to decorative arts, where he studied under the graphic artist Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita.

Travels and Inspiration

The year 1922 was very important for Escher. He traveled through Italy, visiting cities like Florence, San Gimignano, and Rome. In the same year, he also traveled through Spain. He visited Madrid, Toledo, and Granada.

He loved the Italian countryside. In Granada, he was amazed by the Moorish architecture of the 14th-century Alhambra. The detailed designs in the Alhambra were based on geometric symmetries. They had interlocking patterns in the colored tiles and carved walls. This sparked his interest in the math of tessellation. It became a huge influence on his art.

Escher returned to Italy and lived in Rome from 1923 to 1935. In Italy, he met Jetta Umiker, a Swiss woman who also loved Italy. They got married in 1924.

He traveled often, visiting many places like Corsica and Sicily. The towns and landscapes from these trips appear a lot in his artworks. In 1936, Escher went back to Spain. He revisited the Alhambra and spent days drawing its mosaic patterns in detail. This is where he became obsessed with tessellation. He said it was "an extremely absorbing activity, a real mania."

The sketches he made in the Alhambra became a major source for his art from then on. He also studied the architecture of the Mezquita in Cordoba. This was his last long study trip. After 1937, he created his artworks in his studio instead of traveling.

His art changed a lot after this. It went from showing realistic details of nature and buildings to being based on his geometric ideas and imagination. However, even his early work showed his interest in space, unusual views, and different perspectives.

Later Life and Achievements

In 1935, the political situation in Italy became difficult for Escher. The family left Italy and moved to Château-d'Œx, Switzerland, where they stayed for two years.

The Netherlands post office asked Escher to design a postage stamp in 1935 and again in 1949. These stamps were for special events.

Escher had loved the landscapes in Italy, but he was not happy in Switzerland. In 1937, his family moved again to Uccle, a suburb of Brussels, Belgium.

World War II forced them to move once more in January 1941. This time, they moved to Baarn, Netherlands, where Escher lived until 1970. Most of Escher's most famous works come from this period. The often cloudy and wet weather in the Netherlands allowed him to focus deeply on his art.

After 1953, Escher gave many lectures. He planned a series of lectures in North America in 1962, but he had to cancel due to illness. He stopped creating art for a while. However, the drawings and text for these lectures were later published in the book Escher on Escher.

He received an award called the Knighthood of the Order of Orange-Nassau in 1955. He was later made an Officer in 1967.

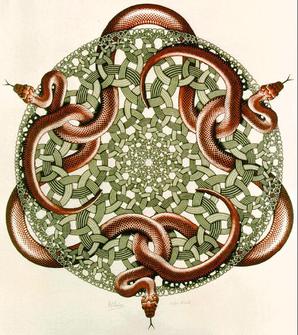

In July 1969, he finished his last work. It was a large woodcut called Snakes. In this artwork, snakes wind through a pattern of linked rings. This image shows Escher's love for symmetry, interlocking patterns, and his ideas about infinity.

Escher moved to the Rosa Spier Huis in Laren in 1970. This was a retirement home for artists where he had his own studio. He died in a hospital in Hilversum on March 27, 1972, at the age of 73. He is buried at the New Cemetery in Baarn.

Art Inspired by Mathematics

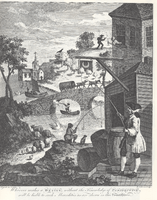

Escher's art is very mathematical. He wasn't the first artist to explore math themes. For example, Parmigianino explored curved shapes and reflections in his 1524 painting Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror. William Hogarth's 1754 Satire on False Perspective also played with errors in perspective, much like Escher.

Another early artist, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, created dark, "fantastic" prints. His Carceri ("Prisons") series shows complex buildings with many stairs and ramps.

In the 20th century, art movements like Cubism and Surrealism started to look at the world in new ways, sometimes with multiple viewpoints, similar to Escher. However, Escher didn't officially join any of these art groups.

-

An early example of curved perspectives and reflections: Parmigianino's Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror, 1524

-

An early example of impossible perspectives: William Hogarth's Satire on False Perspective, 1753

-

An early example of fantastic endless stairs: Piranesi's Carceri Plate VII – The Drawbridge, 1745, reworked 1761

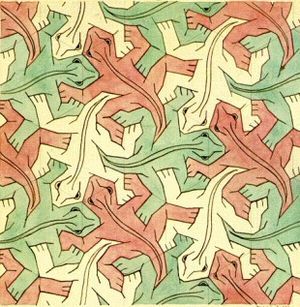

Tessellation: Patterns that Fit Together

In his younger years, Escher sketched landscapes and nature. He also drew insects like ants, bees, and grasshoppers. These insects often appeared in his later artworks.

His early love for Roman and Italian landscapes, along with nature, led to his interest in tessellation. He called this "Regular Division of the Plane." This became the title of his 1958 book. The book included pictures of his woodcuts based on tessellations, where he explained how he built up his mathematical designs. He wrote that "Mathematicians have opened the gate leading to an extensive domain."

After his 1936 trip to the Alhambra and La Mezquita in Cordoba, Escher started to explore tessellation. He used geometric grids as a base for his sketches. He then expanded these into complex interlocking designs, often with animals like birds, fish, and reptiles.

One of his first tessellation attempts was Study of Regular Division of the Plane with Reptiles (1939). It was made on a hexagonal grid. The heads of the red, green, and white reptiles meet at one point. Their tails, legs, and sides fit together perfectly. This study was used for his 1943 lithograph Reptiles.

Impossible Geometries

Escher didn't have formal math training. His understanding of mathematics was mostly visual and intuitive. However, his art had a strong math side. Many of the worlds he drew were built around impossible objects.

After 1924, Escher began sketching landscapes in Italy and Corsica with unusual perspectives. These perspectives are impossible in real life.

His first print showing an impossible reality was Still Life and Street (1937). Impossible stairs and multiple viewpoints appear in popular works like Relativity (1953).

House of Stairs (1951) caught the attention of mathematician Roger Penrose and his father, biologist Lionel Penrose. In 1956, they wrote a paper about "Impossible Objects." They sent Escher a copy. Escher admired their idea of continuously rising flights of steps. He even sent them a print of his work Ascending and Descending (1960). Their paper also showed the Penrose triangle. Escher used this shape many times in his lithograph Waterfall (1961). This artwork shows a building that looks like a perpetual motion machine.

Escher mainly worked with lithographs and woodcuts. The few mezzotints he made are considered masterpieces. In his art, he showed mathematical relationships between shapes, figures, and space. His prints included mirror images of cones, spheres, cubes, rings, and spirals.

Escher was also fascinated by mathematical objects like the Möbius strip, which has only one surface. His wood engraving Möbius Strip II (1963) shows a chain of ants marching forever over what seems like two sides of an object. But when you look closely, it's actually just one continuous surface. Escher explained it:

An endless ring-shaped band usually has two distinct surfaces, one inside and one outside. Yet on this strip nine red ants crawl after each other and travel the front side as well as the reverse side. Therefore the strip has only one surface.

Platonic Solids and Other Shapes

Escher often put three-dimensional objects into his works. These included Platonic solids like spheres, tetrahedrons, and cubes. He also used mathematical shapes like cylinders and stellated polyhedra. In the print Reptiles, he combined two- and three-dimensional images.

Escher's art is especially popular with mathematicians and scientists. They enjoy how he uses polyhedra and geometric distortions. For example, in Gravitation, animals climb around a stellated dodecahedron.

Levels of Reality in Art

Escher's art came from images in his mind. He didn't just draw what he saw. His interest in different levels of reality in art can be seen in works like Drawing Hands (1948). In this print, two hands are shown, and each one is drawing the other.

Escher's Legacy

Escher's unique way of thinking and his amazing graphics have continued to influence math and art. His work is also very popular in everyday culture.

Art Collections

The M.C. Escher Company manages the rights to Escher's art. The M.C. Escher Foundation handles exhibitions of his artworks.

You can find major collections of Escher's original works at several places:

- The Escher Museum in The Hague, Netherlands

- The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, USA

- The National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, Canada

- The Israel Museum in Jerusalem

- The Huis ten Bosch in Nagasaki, Japan

Influence in Math and Science

Many researchers say Escher's work predicted or directly inspired new ideas in math and science. For example, his art helped with:

- Classifying regular tilings (patterns that cover a surface without gaps).

- Understanding color symmetry in crystallography (the study of crystals).

- Ideas about how shapes can change, like in topology.

- Filling empty spaces in art, like in his lithograph Print Gallery.

The 1979 book Gödel, Escher, Bach by Douglas Hofstadter won a Pulitzer Prize. It talks about ideas like self-reference and "strange loops." It uses Escher's art and the music of J. S. Bach as examples.

In 1985, an asteroid was named 4444 Escher in his honor.

Images for kids

-

Doris Schattschneider's reconstruction of the diagram of hyperbolic tiling sent by Escher to the mathematician H. S. M. Coxeter

See also

In Spanish: M. C. Escher para niños

In Spanish: M. C. Escher para niños