Greenpeace facts for kids

Logo of Greenpeace

|

|

Global map of Greenpeace office locations

|

|

| Formation | 1969 – 1972 (see article) Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada |

|---|---|

| Type | International NGO |

| Purpose | Environmentalism, peace |

| Headquarters | Amsterdam, Netherlands |

|

Region served

|

Worldwide |

|

Executive Director

|

Mads Christensen |

|

Main organ

|

Board of directors, elected by the Annual General Meeting |

|

Budget

|

€ 103.735 million (2022) |

|

Staff

|

3,476 (2022) |

|

Volunteers

|

34,365+ (2022) |

| Website | greenpeace.org |

|

Formerly called

|

Don't Make a Wave Committee (1969–1972) |

Greenpeace is a global organization that works to protect our planet. It started in Canada in 1971. A group of environmental activists wanted to make a difference. Greenpeace aims to make sure Earth can support all life. They focus on big issues like climate change, cutting down forests, and too much fishing. They also work on stopping commercial whaling and promoting peace.

Greenpeace uses different ways to reach its goals. These include peaceful protests, doing research, and speaking up for the environment. The organization is made up of 26 independent groups. These groups are in over 55 countries around the world. Greenpeace International, their main office, is in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Greenpeace does not take money from governments or big companies. They rely on donations from millions of individual supporters. This helps them stay independent. Greenpeace is known for its nonviolent actions. It is one of the most recognized environmental groups. They have helped people learn more about environmental problems. They have also influenced both businesses and governments.

Contents

- History of Greenpeace

- How Greenpeace Works

- Greenpeace's Main Goals

- Climate and Energy Work

- Forest Protection Work

- Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs)

- Toxic Waste Campaigns

- Save the Arctic Campaign

- Protecting Oceans from Deep Sea Mining

- Greenpeace Ships

- Reactions to Greenpeace's Work

- Images for kids

- See also

History of Greenpeace

How Greenpeace Started

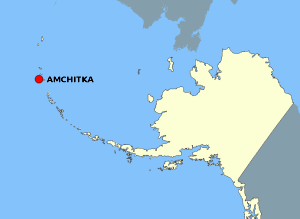

In the late 1960s, the U.S. planned to test a nuclear weapon underground. This test was on Amchitka island in Alaska. People were worried it could cause earthquakes or a tsunami. Thousands protested, but the test still happened.

Later, the U.S. planned an even bigger bomb test. More people joined the protests. Among them were Jim Bohlen and Irving Stowe. They were frustrated that other groups weren't doing enough. Jim Bohlen's wife, Marie, suggested sailing a boat to Amchitka. This idea was inspired by earlier anti-nuclear voyages.

In 1970, the Don't Make a Wave Committee was formed for this protest. Early meetings were held in homes in Vancouver, Canada. Irving Stowe organized a concert to raise money. This concert helped fund the first Greenpeace campaign.

The committee rented a ship called the Phyllis Cormack. They renamed it Greenpeace for the protest. This name was suggested by activist Bill Darnell. On September 15, 1971, the ship sailed towards Amchitka. The U.S. Coast Guard stopped them. But news of their journey spread. It gained a lot of support for their cause. The U.S. later decided to stop its nuclear tests at Amchitka.

Who Started Greenpeace?

Many people helped start Greenpeace. It wasn't just one person. Environmental historian Frank Zelko says the "Don't Make a Wave Committee" began in 1969. The Greenpeace website says the protest voyage in 1971 was "the beginning."

Early members were a diverse group of activists. Greenpeace itself says there was no single founder. The name, ideas, and ways of protesting came from different people. Some key founders of the Don't Make a Wave Committee include Dorothy and Irving Stowe, Marie and Jim Bohlen, Ben and Dorothy Metcalfe, and Robert Hunter.

After the Amchitka Protests

After the nuclear tests at Amchitka ended, Greenpeace focused on new issues. They turned their attention to French nuclear tests. These tests were happening in the atmosphere at the Moruroa Atoll in French Polynesia.

In 1972, a yacht called Vega was renamed Greenpeace III. It sailed into the test zone to protest. The French Navy tried to stop the protest. They even assaulted David McTaggart, the boat's owner. But a crew member photographed the incident. When the photos were shared, France announced it would stop atmospheric nuclear tests.

In the mid-1970s, Greenpeace members also started protesting commercial whaling. They sailed to face Soviet whalers. Activists put themselves between the harpoons and the whales. Videos of these protests were seen worldwide. Later, Greenpeace also began working on issues like toxic waste and seal hunting.

How Greenpeace Grew

Greenpeace grew from a small group into a global movement. By 1977, there were many independent Greenpeace groups. But the Canadian office faced financial problems. This led to disagreements among the groups.

David McTaggart pushed for a new structure. He wanted all the groups to be part of one global organization. The European Greenpeace groups helped pay the Canadian office's debt. On October 14, 1979, Greenpeace International was created. This new structure helped coordinate efforts worldwide.

How Greenpeace Works

Organization and Leadership

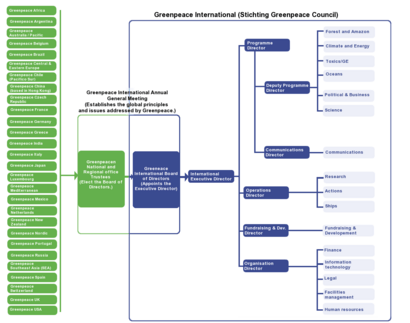

Greenpeace International is based in Amsterdam, Netherlands. It oversees 25 regional offices in 55 countries. These regional offices work mostly on their own. But they follow the guidance of Greenpeace International.

The executive director of Greenpeace International is chosen by its board members. The current international executive director is Mads Flarup Christensen. Greenpeace has about 2,400 staff members and 15,000 volunteers globally.

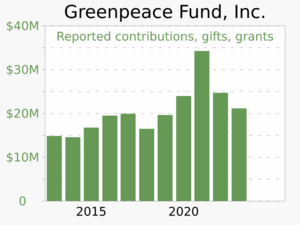

How Greenpeace Gets Money

Greenpeace gets its money from individual supporters and foundations. They carefully check all large donations. This ensures they don't get money from sources that could influence their work. They do not accept money from governments, political parties, or corporations. This helps them stay independent.

In 2008, most of their funding came from about 2.6 million regular supporters. Most of these supporters were from Europe. Greenpeace also pioneered "face-to-face fundraising." This is where fundraisers talk to people in public places. They ask them to sign up for monthly donations.

Greenpeace's Main Goals

Greenpeace is an independent group. They use peaceful but direct actions. Their goal is to show environmental problems. They also work to find solutions for a green and peaceful future. They want to make sure Earth can support all life.

This means they want to:

- Stop the planet from warming too much. This prevents the worst effects of climate change.

- Protect all kinds of life on Earth.

- Help people consume less. They want us to live within Earth's limits.

- Promote renewable energy. This can power the world cleanly.

- Encourage peace, global disarmament, and non-violence.

Climate and Energy Work

Greenpeace was one of the first groups to suggest ways to fight climate change. They did this in 1993. They helped people become more aware of global warming in the 1990s. Greenpeace also focused on chemicals called CFCs. These chemicals harm the ozone layer and cause global warming.

In the early 1990s, Greenpeace helped develop a CFC-free refrigerator technology. It was called "Greenfreeze." This technology was used to make refrigerators for everyone. By 2011, over 600 million refrigerators used Greenfreeze technology. The United Nations Environment Programme honored Greenpeace for this work in 1997.

Today, Greenpeace believes global warming is Earth's biggest environmental problem. They want to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to almost zero by 2050. They also want rich countries to cut their emissions by 40% by 2020. They also ask for money to help developing countries use clean energy.

Greenpeace often protests against coal. They have occupied coal power plants. They have also blocked coal shipments and mining. They also criticize getting oil from oil sands. They have used direct action to stop these operations in Canada.

Green Planet Energy

In 1999, Greenpeace Germany started Greenpeace Energy. This was a cooperative that supplied renewable electricity. In 2021, it changed its name to Green Planet Energy. Greenpeace Germany still has a share in this cooperative.

"Go Beyond Oil" Campaign

Greenpeace has a campaign called "Go Beyond Oil." This campaign aims to slow down and stop the world's use of oil. Activists protest against companies that drill for oil. Much of this work focuses on drilling in the Arctic. It also targets areas affected by oil spills, like the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

Greenpeace also puts pressure on governments. They want governments to stop allowing oil exploration. One main goal is to show how far the oil industry will go to get oil. They want to push industries and governments to move past oil.

Nuclear Power Concerns

Greenpeace is against nuclear power. They believe it is "dangerous, polluting, expensive and non-renewable." They point to disasters like Chernobyl in 1986 and Fukushima in 2011. These events show the risks nuclear power can pose to people and the environment.

Greenpeace argues that nuclear power does not help much with global warming. They say it takes too long to build nuclear plants. They also say it costs too much. They believe this takes money away from better solutions. In 2022, Greenpeace said they would sue the European Union. This was because the EU suggested calling nuclear power a "green" technology.

Greenpeace celebrated when Germany stopped using nuclear power in 2023. At that time, Germany was using a lot of coal and gas for energy.

Ozone Layer and Greenfreeze

The ozone layer protects Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation. In 1985, scientists reported that the ozone layer was being damaged. This led to the Montreal Protocol in 1987. This agreement banned chemicals like CFCs used in refrigeration.

Around 1992, a German institute developed a safe alternative. It was a hydrocarbon refrigerant. The rights to this technology were given to Greenpeace. They kept it as an open source patent. This technology was then used in Germany, China, and other parts of the world. By 2012, it was even used in the US.

Action Against New Oil Licenses in the UK

In August 2023, Greenpeace protested new oil exploration licenses in the United Kingdom. They covered the home of Prime Minister Rishi Sunak with black fabric. This action in Yorkshire highlighted their opposition to the new licenses.

Forest Protection Work

Greenpeace works to protect natural forests from being cut down. Their goal is to stop deforestation completely by 2020. They have accused many big companies of being linked to cutting down tropical rainforests. These companies include Unilever, Nike, KFC, and McDonald's. Because of Greenpeace's actions, some of these companies have changed their policies.

Greenpeace also worked for ten years to get the EU to ban illegal timber. The EU agreed to ban illegal timber in July 2010. Since deforestation adds to global warming, Greenpeace wants it included in climate treaties.

Another Greenpeace campaign focuses on palm oil. They want to stop the mass production of palm oil. This is because it can harm the biodiversity of forests. They are very active in Indonesia, where a lot of land is used for palm oil. Greenpeace encourages industries and governments to find other energy sources. One success was when Golden Agri-Resources, a large palm oil company, promised to help conserve forests.

Greenpeace also created a viral video in 2016. It protested Nestlé's use of palm oil in Kit Kat bars. The video got over 1 million views. Nestlé then said they would stop using such practices. In 2018, Greenpeace released an animated short film. It featured a fictional orangutan named Rang-tan. This was to raise awareness about orangutans and palm oil.

Wilmar International Palm-Oil Issue

In 2018, Greenpeace International investigated Wilmar International. This is the world's largest palm-oil trader. Greenpeace found that Wilmar was still linked to forest destruction in Indonesia. A company connected to Wilmar had caused deforestation. This area was twice the size of Paris. Greenpeace said Wilmar broke its promise from 2013 to end deforestation.

Resolute Forest Products Issue

The logging company Resolute Forest Products has sued Greenpeace several times. Greenpeace says the company's actions are harming the Boreal forest of Canada. Greenpeace believes these forests are very important for protecting the global climate. This is because they hold a lot of carbon. In 2020, a court ordered Resolute to pay Greenpeace money. This was to cover legal costs after most of the company's claims were rejected.

Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs)

Greenpeace has also spoken out against GM food. For example, they supported Zambia's decision to reject GM food from the US. This was as long as non-GM grain was available. Greenpeace said the US should let countries choose their food aid. They also said buying food locally helps developing economies.

Greenpeace has concerns about golden rice. This is a type of rice changed to have more vitamin A. It is meant to help people in poor countries. Greenpeace argues that golden rice has not solved malnutrition in 10 years. They say other methods are already working. Greenpeace suggests growing more crops that are naturally rich in nutrients. They believe resources should go to programs that are already helping.

In June 2016, over 100 Nobel Laureates signed a letter. They asked Greenpeace to stop its campaign against genetically modified crops, especially Golden Rice. Greenpeace replied that claims they are blocking Golden Rice are false. They said they support investing in farming that is good for the climate. They also support helping farmers get healthy food.

Toxic Waste Campaigns

In July 2011, Greenpeace released a report called "Dirty Laundry." It accused some top fashion and sportswear brands of releasing toxic waste into China's rivers. The report showed how chemicals from the textile industry were polluting water. They found dangerous chemicals in samples from factories.

The report said these factories worked with major clothing brands. These included Abercrombie & Fitch, Adidas, Calvin Klein, H&M, Nike, and Puma. In 2013, Greenpeace started the "Detox Fashion" campaign. Many fashion brands joined. They promised to stop releasing toxic chemicals into rivers from their clothes production. This campaign helped bring attention to water pollution from textiles.

Guide to Greener Electronics

In August 2006, Greenpeace published the "Guide to Greener Electronics." This guide ranked mobile and PC makers. It judged them on how green they were. This included how much toxic material they used and their handling of e-waste.

The guide's goals were updated in 2011. They wanted companies to reduce greenhouse gases. They also wanted them to use 100% renewable power. The guide also pushed for long-lasting products without dangerous substances. It also encouraged more sustainable practices. This guide has led to many improvements. Companies have removed toxic chemicals and improved recycling. The last edition was published in 2017.

Save the Arctic Campaign

Greenpeace started the "Save the Arctic" campaign in 2012 and 2013. They want to stop oil and gas drilling, industrial fishing, and military actions in the Arctic region. They asked world leaders at the UN to create a "global sanctuary in the high arctic." This would protect the fragile wildlife and ecosystem.

In September 2013, 30 activists from the MV Arctic Sunrise were arrested. This happened while they were protesting at a Gazprom oil platform in Russia. They were later released.

In July 2014, Greenpeace started a boycott campaign. They wanted Lego to stop making toys with the Shell oil company's logo. This was because Shell planned to drill for oil in the Arctic. Greenpeace released a video called "LEGO: Everything is NOT awesome." It showed the problems with this partnership. The video got over 9 million views.

Norway Protests

Greenpeace has protested against oil rigs in the Arctic Ocean in Norway. In 2013, three activists dressed as bears got onto a Statoil oil rig. They stayed there for about three hours. Greenpeace argued that Statoil's drilling plans were dangerous. They said an oil spill would be very hard to clean up in the Arctic.

In May 2014, Greenpeace's ship, MV Esperanza, took over a Statoil oil rig. This made it unable to operate. Seven activists were on the rig. Norwegian police later peacefully removed them. They were released without fines. The Norwegian Coast Guard then towed away the Esperanza. Greenpeace continues to criticize Statoil. They say the company is "greenwashing" its image. This means they try to look environmentally friendly while doing risky oil drilling.

Protecting Oceans from Deep Sea Mining

Greenpeace and other groups want to stop deep sea mining. This mining is allowed by the International Seabed Authority (ISA). Greenpeace says mining for metals on the ocean floor could harm the world's oceans. Oceans absorb a lot of the world's carbon emissions. Deep sea mining also disturbs the homes of many sea creatures.

Greenpeace believes the ISA is not the right group to manage deep sea mining. In 2019, Greenpeace activists protested at the ISA meeting in Jamaica. They called for a global ocean treaty. This treaty would ban deep sea mining in ocean sanctuaries.

Greenpeace Ships

Ships have always been important for Greenpeace campaigns. They have used many different vessels over the years.

Ships in Service Today

- Rainbow Warrior: This is the third ship with this name. It was launched in 2011.

- MV Arctic Sunrise

- SY Witness

Past Ships

First Rainbow Warrior

In 1978, Greenpeace launched the first Rainbow Warrior. It was a former fishing boat. The name came from a book called Warriors of the Rainbow. This book inspired early activist Robert Hunter. Greenpeace bought the ship and volunteers fixed it up.

The Rainbow Warrior was used to protest whaling and the dumping of toxic waste. In May 1985, it helped move about 300 islanders from Rongelap Atoll. Their home had been contaminated by a US nuclear test.

Later in 1985, the Rainbow Warrior was going to protest French nuclear tests. These tests were at Moruroa atoll. But the French government secretly bombed the ship in Auckland harbor. This happened on orders from their president. A photographer named Fernando Pereira was killed. He drowned after a second explosion. This attack was a big public relations disaster for France. The New Zealand police quickly found out what happened. France later apologized and paid compensation.

Second Rainbow Warrior

In 1989, Greenpeace got a new Rainbow Warrior. It was sometimes called Rainbow Warrior II. This ship was used until August 2011. It was then replaced by the third Rainbow Warrior. In 2005, the Rainbow Warrior II accidentally hit the Tubbataha Reef in the Philippines. Greenpeace paid a fine for the damage. They said they felt responsible, even though they had outdated maps.

Reactions to Greenpeace's Work

Greenpeace has faced lawsuits from companies. Some companies have also spied on Greenpeace. They have even sent people to work inside Greenpeace offices. Greenpeace activists have also faced threats and violence. The bombing of the Rainbow Warrior was an act of state terrorism.

In May 2023, Russia's Prosecutor-General's Office called Greenpeace an "undesirable organization." They accused Greenpeace of interfering with Russia's internal affairs.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Greenpeace para niños

In Spanish: Greenpeace para niños

- 1971 in the environment

- 350.org

- Climate Reality Project

- Climate Clock

- European Renewable Energy Council

- Friends of Nature

- Fund for Wild Nature

- How to Change the World (2015 documentary film about Greenpeace)

- List of years in the environment

- Sea Shepherd Conservation Society

- World Wide Fund for Nature

- Greenpeace USA

- Greenpeace Australia Pacific