Hallett Cove Conservation Park facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hallett Cove Conservation ParkSouth Australia |

|

|---|---|

|

IUCN Category III (Natural Monument)

|

|

| Nearest town or city | Adelaide |

| Established | 1 July 1976 |

| Area | 51 ha (126 acres) |

| Managing authorities | Department for Environment and Water |

| Website | Hallett Cove Conservation Park |

| See also | Protected areas of South Australia |

Hallett Cove Conservation Park is a special protected area. It is located in Hallett Cove, right on the coast of Gulf St Vincent. This park is about 22 kilometres south of Adelaide, the capital city of South Australia.

Hallett Cove is one of Australia's most famous geological spots. It is known worldwide for its amazing rocks and landforms. The Geological Society of Australia has even called it a "Geological Monument." It is also listed on the South Australian Heritage Register because it is so important for learning and science.

This area is also very important for archaeology. Scientists have found signs of some of the earliest Aboriginal people living here. These signs date back as far as 40,000 years ago!

Inside the park, you can find cool features like Waterfall Creek, Black Cliff, and the Amphitheatre. A fresh water spring near Waterfall Creek is a key part of the Tjilbruke Dreaming Track.

Contents

History of Hallett Cove

Ancient Aboriginal Life

Aboriginal people have lived in the Hallett Cove area for a very long time. It is one of the oldest known places where Aboriginal people settled in Australia. Scientists have found over 1,700 large stone tools near the coast. They also found a campsite at Waterfall Creek.

These tools show that the Kartan people from Kangaroo Island lived here about 40,000 years ago. The first tools were found in 1934 by Harold More Cooper. He worked at the South Australian Museum. More tools were found over the next 36 years.

Most of these tools are heavy Kartan stone tools. They can weigh up to 5.5 kilograms. Over 400 were found around a large camp. This shows that people lived here during the late Pleistocene period. Over time, smaller tools started to be used.

Kartan tools are usually made of quartzite. This rock often came from far away. But all the tools found at Hallett Cove were made of siltstone. This is strange because there was a lot of quartzite on the beach.

During the late Pleistocene, the sea level was much lower. It was about 90 metres lower than it is today. The area that is now Gulf St Vincent was a deep river valley. The closest quartzite was probably 350 kilometres south. It is thought that local quartzite was covered by rock and dirt. It only became exposed after the coastline formed about 6,000 years ago.

More recently, the Kaurna people lived here. They had two campsites dating back 2,000 years. Their middens (ancient rubbish heaps) contain shellfish remains. They also have earbones from Mulloway fish. Smaller camps were found on the cliff edge. These might have been used by people watching for Mulloway fish migrating.

Hallett Cove is very important to the Kaurna people. It is linked to the Dreaming story of Tjilbruke. He is their creator ancestor. The Tjilbruke Dreaming story talks about seven freshwater springs south of Adelaide. One of these springs is likely near Waterfall Creek. This spring is surrounded by many campsites, both very old and more recent. There are special commemorative plaques. They mark important spots on the Dreaming track. One is at the reserve on Keerab Way. Another is at the first spring, said to be made by Tjilbruke's tears. This is on the foreshore at Heron Way.

European Discoveries and Protection

After the British colonisation of South Australia, the area was named Hallett Cove. It was named after John Hallett. He explored the area in 1837. In the 1840s, the cove was used by smugglers. They would bring goods ashore at night. Then they would take them to Adelaide by cart.

In 1847, the Worthing Mining Company bought land here. They built a copper mine. But the ground was too hard, and water kept flooding the mine. In 1852, the miners left for the Victorian gold rush. The mine was finally closed in 1857. Farming started in the eastern part of the park in the 1850s. In the late 1880s, the cove was used for naval training. Rocks were cleared from the southern beach for landings.

In 1877, Professor Ralph Tate made an important discovery. He found smooth, scratched rocks called a glacial pavement. This showed that South Australia had once been covered by ice during an ice age. In 1893, a huge science trip explored the area. Professor Walter Howchin later showed that the rock layers were from the Permian period. This meant Australia was much closer to the South Pole back then. It was part of a supercontinent called Gondwana. During that time, much of South Australia was covered by a huge ice sheet.

In 1957, Professor A.R. Alderman suggested that the glacial pavements should be protected. In 1960, a local farmer named George Sandison passed away. His family donated land along the cliffs to the National Trust of South Australia. More land was given for an access road. In 1965, this land became The Sandison Reserve.

In 1965, plans were made to build houses nearby. For 11 years, people who cared about nature fought against these plans. In 1969, the government declared 51 hectares of Hallett Cove a special scientific site. This stopped landowners from building anything that would harm its scientific value. In 1970, there were plans for a large private marina in the cove. Many people protested. The government received thousands of letters. Premier Don Dunstan promised to protect the area. The government then bought the cove and more land. In 1976, the park was officially named a Conservation Park. It was set up to protect its amazing geology and history.

Geology of the Park

Ancient Precambrian Rocks

The oldest rocks at Hallett Cove are about 600 million years old. They have ripple marks, which means they formed on a tidal plain. This was during the upper Precambrian period. This plain was part of a shallow sea. To the west was an ancient landmass. To the east was a deep ocean. The eastern half of Australia had not yet formed.

This shallow sea stretched for about 700 kilometres. It went from the northern Flinders Ranges to Kangaroo Island. The sea lay over a sinking area called the Adelaide Geosyncline. This area slowly sank as mud and sand built up. This kept the water shallow for millions of years. The sediments piled up to a depth of 8 to 10 kilometres.

Around 550 million years ago, the rocks in the Geosyncline started to bend and fold. They also uplifted and broke into blocks. This created a mountain range called the Delamerian Highlands. These mountains might have been as tall as 8 kilometres! Soon after, the mountains began to wear away. This erosion continued for another 200 million years.

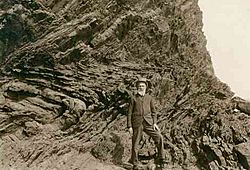

The Precambrian rock of Black Cliff and the flat platform at Hallett Cove are what is left of the base of these mountains. You can clearly see complicated folds and small breaks in the rock. Erosion has removed younger rocks from this area. But younger rocks (570-500 million years old) are found further south. These are between Sellicks Hill and Normanville. Cambrian fossils have been found in these younger rocks. No fossils have been found in the rocks at Hallett Cove.

Today, the southern part of this ancient mountain range is called the Mount Lofty Ranges. They have worn down to less than 730 metres high.

The Permian Ice Age

The 600-million-year-old Precambrian rocks at Hallett Cove are separated from the 270-million-year-old Permian rocks. This means there is a big gap in time. If any rocks formed between these two periods, they have been completely worn away.

The formation of the supercontinent Pangaea led to a lot of ice covering Australia. This happened during the Carboniferous and Permian periods. By 270 million years ago, Australia was part of a huge continent called Gondwana. Crescent-shaped cracks in the glaciated rocks at Hallett Cove show how the ice moved. It flowed north and northwest, towards what is now the centre of Australia. This means the ice came from high land to the south. If scientists are right about continental drift, this land was Antarctica.

The rocks at Hallett Cove show not only that glaciers passed through, but also that they melted and retreated. Hallett Cove was part of a river valley at this time. Ice had carved out a basin. Meltwater from the retreating glacier formed a lake. This lake deposited the sediments you can see today along the clifftops. No fossils have been found in these sediments. However, arthropod trails have been found in similar sediments further south.

Dropstones and erratics are rocks carried by glaciers. When the ice melts, they are dropped. Many of these rocks are scattered on the beach. The Permian sediments that once held them have long since worn away. You can still find smaller ones stuck in the sediments. Most of the dropstones, some bigger than cars, came from hundreds of kilometres to the south. But some are made of rock not found in South Australia. Their origin is still a mystery. One large erratic is currently wearing out at the top of Black Cliff. It is 400 million years older than the oldest Hallett Cove rocks. It is made of Tillite. This is the earliest evidence of glaciation ever found on Earth.

The Pliocene Period

A second period of erosion started around 250 million years ago. This removed most of the Permian sediments in the area. Only some were protected by the Hallett Cove basin. This creates another gap in the rock record. It separates the Permian rocks from the Pliocene deposits.

By the Cenozoic Era, the Mount Lofty Ranges had worn down to sea level. Then, a period of faulting began. This lifted the ranges and pushed down the plains. Starting 50 million years ago, the sea flooded these plains. By 20 million years ago, the land west of the ranges was a shallow sea. Hallett Cove has no sediments from this time. This suggests it might have been above sea level, like an island in a shallow sea.

More faulting raised the Mount Lofty Ranges even higher than they are now. This also submerged Hallett Cove. A layer of sandstone, dating from 5 to 3 million years ago, can be found on top of the Permian deposits. This sandstone formed on a sea floor. It contains fossil shells and limy sands. On top of the sandstone is a thick layer of mottled clays. These clays have patches of sand and gravel. They were washed down from the slopes of the Mount Lofty Ranges. This happened from 3 to 1 million years ago, when the area was a river flood plain.

The Pleistocene Climate

The Pleistocene climate was marked by many repeated ice ages. During the early Pleistocene, a lot of clay built up quickly. This shows that the climate was much wetter than it is today. The last ice age ended 15,000 years ago. After that, the climate seems to have become drier. A layer of calcrete (a hard crust) formed on top of the clay deposits.

The Gulf St Vincent was a flat plain with a river when Aboriginal people first settled on the Hallett Cove clifftops. Their tools have been found in the sand that lies above the calcrete.

Recent Changes to the Coastline

As the glaciers melted in the Northern Hemisphere, sea levels rose all over the world. The current sea level became stable about 6,000 years ago. This rising sea began to wear away the Hallett Cove cliffs. The rock layers in the cliff face are almost straight up and down. As the sea erodes the softer layers, it creates the zigzag pattern we see today. As the cliff wears away, it leaves a flat, rocky platform behind.

The Amphitheatre is a special part of the park. Here, the ancient Precambrian rocks are below sea level. Without their protection, the sea is quickly cutting through the softer Permian, Pliocene, and Pleistocene layers. This creates a badlands landscape. As the soft mud and sand are eroded, erratics (large rocks carried by glaciers) are released. They roll down to the base platform and the beach.

There is a walking trail in the park. It helps you learn about the park's cultural history and amazing geology.

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |