History of Poznań facts for kids

Poznań is one of Poland's oldest and most important cities. Today, it's the fifth largest city in the country. Long ago, in the 10th century, it was a major center for politics and religion in the early Polish state. The Poznań Cathedral is Poland's oldest church, and it holds the tombs of the very first Polish rulers, like Duke Mieszko I and King Bolesław I Chrobry.

Even though the main capital of Poland moved to Kraków and then Warsaw, Poznań stayed a very important city in the Greater Poland region. For a long time, from 1793 to 1918, it was ruled by Prussia (which later became Germany). During this time, the city grew a lot and was also strongly fortified with many forts. Poznań became a Polish regional capital again after World War I in the Second Polish Republic. After the Nazi German occupation (1939–1945), it was part of the communist Polish People's Republic. Since 1999, Poznań has been the capital of the Greater Poland Voivodeship.

Contents

- Poznań's Early History (Before 1138)

- Poznań During Poland's Fragmentation (1138–1320)

- Poznań in Poland and the Commonwealth (1320–1793)

- Under Prussian Rule (1793–1807)

- Under the Duchy of Warsaw (1807–1815)

- Under Prussian Rule Again (1815–1918)

- Between the World Wars

- World War II

- Poznań Since 1945

- See also

Poznań's Early History (Before 1138)

People first settled in the area of Poznań during the late Stone Age. Over time, different cultures lived here during the Bronze Age and Iron Age.

Poznań started as a strong fort built in the 8th or 9th century AD. It was located between two rivers, the Warta and Cybina, on what is now called Ostrów Tumski ("Cathedral Island"). Other small settlements grew up nearby. In the 10th century, the Polans tribe, who lived here, became very powerful. They took control of most of what is now Poland. Because of this, the early Polish state, led by Duke Mieszko I and his family (the Piast dynasty), had its main political centers in Poznań and nearby forts like Gniezno.

Archaeologists have found that in the late 10th century, Poznań had a ducal palace. This palace, where the Church of Our Lady now stands, even had a chapel. It might have been built for Mieszko's Christian wife, Dobrawa. Many historians believe that Mieszko I converted to Christianity in 966, an event called the Baptism of Poland, and that this important event happened in Poznań.

After Mieszko became Christian, Poland received its first missionary bishop, Jordan, in 968. He likely made Poznań his base. Building then began on Poznań's cathedral. It was first built in an early Romanesque style and was dedicated to St. Peter. The first rulers of Poland – Mieszko I, Bolesław I, and Mieszko II – are buried under this cathedral.

In 1000, Gniezno became an archbishopric (a very important church center) during the Congress of Gniezno. This was agreed upon by King Bolesław I and Holy Roman Emperor Otto III. However, Bishop Unger, who followed Jordan, stayed in Poznań and was independent of Gniezno.

When Mieszko II died in 1034, Poland went through a difficult time of chaos and pagan uprisings. This caused a lot of damage. In 1038, Bretislaus I, Duke of Bohemia invaded, destroying Poznań and Gniezno. When Poland was reunited by Casimir the Restorer in 1039, the capital moved to Kraków, which had not been as damaged. Poznań and Gniezno were rebuilt, and even though the region was no longer the main political center, Poznań remained an important place for trade and business.

Poznań During Poland's Fragmentation (1138–1320)

In 1138, King Bolesław III Krzywousty divided Poland among his sons. Poznań and its area became the land of Mieszko III the Old, who was the first Duke of Greater Poland. This period was full of fighting among the dukes, and different parts of the region often changed hands. Mieszko III was the High Duke of all Poland at different times. By the time he died in 1202, he controlled all of Greater Poland, making Poznań a powerful center. But the fighting continued through the 13th century.

At this time, Poznań was still mainly the fort on Cathedral Island. However, by the late 12th century, small towns for trade and crafts grew up around it. These included St. Gotard, St. Martin, and St. Adalbert (Wojciech) on the left bank of the Warta River, and Śródka on the right bank. The name Śródka came from the Wednesday markets held there (środa means "Wednesday" in Polish).

The main growth happened on the left bank. Around 1249, Duke Przemysł I started building a home and castle on what is now Przemysł Hill. This would become the Royal Castle. In 1253, Przemysł and his brother Bolesław the Pious officially allowed a new town to be built under Magdeburg law. This law gave the town special rights and freedoms. Many German settlers came to help build this new city. This city covered the area of Poznań's current Old Town, with its center at the Market Square (now Stary Rynek). Under Duke Przemysł II, the castle was made stronger, and the new city was surrounded by a wall that connected to the castle.

Przemysł II was crowned king of Poland in 1295, making the castle a royal home. But after he was killed in 1296, the fighting started again. In 1314, Poznań finally came under the control of Władysław I the Elbow-high. He was crowned king of a reunited Poland in 1320, ending the period of fragmentation.

Poznań in Poland and the Commonwealth (1320–1793)

In the reunited Poland, Poznań became the capital of a voivodeship (a type of region). Poznań grew more important during the Jagiellonian period because it was on a major trade route from eastern Europe to western Europe. Kings like Władysław II Jagiełło gave the city many special rights, and it continued to grow. Most of the smaller towns around Poznań on the left bank of the Warta belonged to the city. However, Cathedral Island (Ostrów Tumski) and the right bank were owned by the bishop. Other towns like Ostrów Tumski (before 1335), Śródka (1425), and Chwaliszewo (1444) also gained their own town rights.

The city often suffered from diseases, which slowed its growth. It also had many fires (in 1386, 1447, 1459, 1464, 1536, and 1590), which made people use more brick instead of wood for building. Floods were also a common problem. The city's defenses were made stronger from 1431 onwards with new wall towers and a second line of walls.

Poznań had a large Jewish community, probably since the mid-13th century. The first official record of them is from 1367. The Jewish quarter was in the northeast of the walled city, around "Jewish Street" (ulica Żydowska).

The Lubrański Academy was founded in Poznań in 1519. It was Poland's second higher education school after the Jagiellonian University, but it couldn't give out official academic degrees.

In 1536, a big fire damaged much of the city, including the town hall. This led to a major redesign and rebuilding of the town hall between 1550 and 1560.

By 1549, there were about 550 houses belonging to townspeople, 86 to Jews, and about 30 each to nobles and clergy. Many craftsmen had moved outside the city walls. The total population of the area was about 20,000, with 8,000 living inside the city walls. However, the population changed a lot due to fires, floods, and diseases. At the end of the 16th century, Poznań was a major center for trading furs and leather.

During the "free election" period in Poland, Poznań was one of the most important cities and had voting rights.

Attempts were made to bring Protestantism to the city in the late 16th century, but most people remained Roman Catholic. The Catholic Church fought back with the Counter-Reformation, including founding a Jesuits' College in the city in 1571. This college could give out degrees from 1611.

From the mid-17th century, Poznań, like all of Poland, suffered from many invasions and disasters. The city was taken by a Swedish army in 1655 during the Second Northern War, then by Brandenburgian forces in 1656. The Swedes burned the suburbs when they left. The city was badly damaged after a two-month siege in 1657. There were also many deaths from plague. In the Third Northern War, Poznań was again occupied by a Swedish army from 1703–1709. After 1709, Saxon forces took over and looted the city. More outbreaks of plague continued until 1711.

A fire on March 16, 1717, spread from the Jewish quarter to the whole city. King August II did not help much with rebuilding. In 1719–1753, Poznań invited many rural settlers from Bamberg (called Bambrzy) to help rebuild the damaged suburbs. There were also Dutch settlers (Olędrzy).

Poznań was affected by the Seven Years' War (1758–1763) because of its important location. Russian and Prussian troops took turns occupying the city, looting property. The city received no help from the Polish government. Poznań also suffered during the Bar Confederation conflict, with Russian and confederate troops occupying the city at different times.

In 1778, a "Committee of Good Order" was set up in Poznań to help restore the city. It was led by Kazimierz Raczyński. The committee took inventory, showing 390 residential buildings and 57 public buildings within the city walls. There were also 8 abbeys, 9 Catholic churches, a Protestant church, and a synagogue. The committee organized repairs, built new buildings, improved streets, and tried to make the river navigable. It also reformed the city government.

On January 31, 1793, a Prussian army occupied Poznań. On June 10, an order was given that all Polish government offices must stop working by July 4. This meant Poznań (or Posen, as it was called in German) and all of Greater Poland came under Prussian rule.

Under Prussian Rule (1793–1807)

In 1794, Prussian records showed about 15,000 people living in the Poznań area. About 70% were Polish, 20% Jewish, and 10% German.

Poznań became part of the province of South Prussia. The Prussian authorities wanted to combine all the settlements into one city. In 1796, lands belonging to the Church were taken, and in 1797, St. Wojciech and St. Martin were added to the city. In 1800, the island settlements of Chwaliszewo and Zagórze, and Śródka, Ostrówek, and Zawady on the right bank were also included.

By this time, the city covered about 7.8 square kilometers (3 square miles) and had nearly 19,000 people, plus a garrison of 2,500 soldiers. The old city walls were no longer needed, so they were taken down and the moats filled in. This allowed the city to expand. New streets and squares were built, like Wilhelms Strasse (today's Aleje Marcinkowskiego). A fire in 1803 caused a lot of damage in the old town, leading to wider streets being planned. In 1804, a theater called Arkadia was built, mainly for German plays.

Under the Duchy of Warsaw (1807–1815)

After France won battles against Prussia in the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon sent Polish generals Jan Henryk Dąbrowski and Józef Wybicki to create a Polish army. They were to take control of South Prussia in what was called the Greater Poland Uprising of 1806. On November 3, 1806, Dąbrowski and Wybicki entered Poznań as Prussian forces left. The city became a base for military actions. Napoleon himself stayed in Poznań from November 27 to December 12. In 1807, Poznań became part of the Duchy of Warsaw, a semi-independent Polish state, and was the capital of the Poznań Department.

In 1812, Napoleon's armies passed through Poznań again, this time retreating after their defeat in Russia. Napoleon secretly stayed in the city on December 12. The last French troops left on February 12, 1813, and Russian troops entered the city the same day. This Russian occupation lasted until 1815. In that year, as decided at the Congress of Vienna, Poznań and its region again came under Prussian control.

Under Prussian Rule Again (1815–1918)

In 1815, Poznań had 23,854 people. The city became the capital of the Grand Duchy of Posen. This duchy was supposed to have some freedom, and the rights of Poles were to be respected. However, in reality, efforts were made to make the area more German. Poznań was the seat of the royal governor, Duke Antoni Henryk Radziwiłł. The city continued to grow, with new streets and the demolition of old city walls. Plans were also made for new forts around the city, including the Fort Winiary citadel in the north. Building on this project began in 1828 and continued for many years.

In 1828, the famous composer Fryderyk Chopin visited the city.

One important project funded by Poles was the Raczyński Library, completed in 1828. It was paid for by Edward Raczyński. The Bazar hotel on Wilhelms Strasse, built in 1841, also became a key center for Polish culture. In 1841, Karol Marcinkowski and Maciej Mielzynski founded a society that gave scholarships to poor Poles. Raczyński also paid for the city's first water supply system in 1840. Hipolit Cegielski opened his first metal goods shop in the Bazar hotel in 1846. His company, Cegielski, would become one of Poznań's largest factories.

In the 1830s, there was talk of building a railway to Frankfurt an der Oder. But the Prussian authorities were worried about Russia using it in a war. A railway was finally approved in 1846, going north to Stargard. It opened on August 10, 1848. The main train station was built in 1879. A direct line to Warsaw wouldn't open until 1921.

Polish people in the region rebelled against Prussian rule in two uprisings, known as the "Greater Poland Uprising." The 1846 uprising was quickly defeated. The 1848 uprising had more success at first, but it also failed. After these events, the Duchy lost its special freedom and became the Province of Posen. In 1871, this province became part of the united German Empire.

Polish social and academic groups continued to form, like the Poznań Society of Friends of Learning (1875). In 1873–1875, a Polish theater (Teatr Polski) was built. However, the authorities kept trying to make the region more German. Germans made up 38% of the city's population in 1867. By 1910, their number grew to 50,000, but they were a smaller percentage of the total population because the city had grown so much.

A gasworks was built in 1853–1856, providing the first gas streetlights in 1858. The city's first modern waterworks (1866) and major electricity works (1904) were also built. Sewers were installed on a large scale in the late 19th century.

To make the city's defenses stronger, a new outer ring of forts was built around Poznań starting in 1876. Poznań became a major military base. Much of the old inner forts were taken down, allowing the city to expand, especially to the west. Near the old Berlin Gate, impressive buildings were constructed, including the imperial palace (now called Zamek), finished in 1910. Other buildings included the opera house and a Royal Academy.

Serious floods happened in 1855, 1888, and 1889. In 1889, Emperor Wilhelm II visited to see the flood damage. Plans were made to change the course of the Warta River, but this didn't happen until 1968.

Poznań got its first electric trams in 1898 (horse-drawn trams had been running since 1880). The first cars appeared in 1901, and taxis in 1905.

In 1896, the suburbs of Piotrowo and Berdychowo became part of the city. The city borders expanded significantly westward in 1900 to include Łazarz, Górczyn, Jeżyce, and Wilda. Sołacz was added in 1907. Poznań now covered about 33.9 square kilometers (13.1 square miles). From 1911–1913, the St. Roch road bridge was built across the Warta.

Between the World Wars

After Germany lost World War I, Poland was set to become independent. However, it wasn't clear if Greater Poland would be part of the new country. A speech by Ignacy Paderewski in Poznań on December 27, 1918, sparked the Greater Poland Uprising of 1918–1919. Polish troops fought to take control of the region from Germany. The uprising was largely successful, and in the Treaty of Versailles (signed June 28, 1919), most of the region became part of Poland. Poznań became the capital of the new Poznań Voivodeship in the Second Polish Republic. Many German residents left, partly due to discrimination. Germans made up only 5.5% of the city's population in 1921.

In 1919, Poznań University opened. In 1921, Poznań started hosting trade fairs, which became the Poznań International Fairs in 1925. From May 16 to September 30, 1929, the fairgrounds hosted a huge National Exhibition (Powszechna Wystawa Krajowa). This exhibition celebrated ten years of Polish independence and attracted about 4.5 million visitors.

Between the wars, the city's borders expanded again in 1925 and 1933, nearly doubling its size to 76.9 square kilometers (29.7 square miles).

World War II

German troops invaded Poznań on September 10, 1939, during the invasion of Poland that started World War II. Soon after, special German units entered the city to commit terrible things against the people. In September, the occupiers arrested many Poles and carried out mass killings. They also searched Polish institutions and closed down Polish organizations. On October 8, 1939, Poznań was taken over by Germany and became part of a new province called Reichsgau Wartheland.

During the German occupation, many people were murdered, executed, or held in terrible conditions. About 100,000 people were forced to leave their homes and move to other parts of German-occupied Poland. The Germans wanted to slowly get rid of the Polish and Jewish people in the region. Many others were sent to Germany as forced laborers or made to join the German army.

Poles were forced to work in the city. From 1941, the German labor office in Poznań demanded that Polish children as young as 12 register for work, and even ten-year-olds were forced to work. In 1943, the Germans also sent kidnapped Polish children from Poznań to a camp in Łódź, which was called "little Auschwitz" because of its awful conditions.

From 1940 to 1945, the Germans ran a prisoner-of-war camp for Allied soldiers in Poznań.

The Polish resistance movement was active in the city. Many secret organizations were formed in Poznań. They carried out secret Polish schooling, printed underground newspapers, did sabotage, trained soldiers, spied on German activities, helped people in need, and helped British prisoners of war escape. In February 1943, a unit of the Home Army burned down German warehouses in the river port.

The Nazi authorities greatly expanded the city boundaries between 1940 and 1942, almost tripling its size to 226 square kilometers (87 square miles). They also changed Polish district names to German ones. The Polish names were restored after the war, but the expanded city boundaries remained.

As the Soviet Red Army moved into Poland in January 1945, Poznań was declared a "fortress" that had to be defended at all costs. Soviet forces reached the city on January 25. After nine days of artillery attacks, they began their ground assault on February 18. On February 22, the German commander died, and the remaining soldiers surrendered the next morning. The fighting destroyed over 55% of the city, including over 90% of the Old Town. For more details, see Battle of Poznań (1945).

Poznań Since 1945

Many Germans had fled as the Soviets advanced. After the war, the expulsion of Germans from Polish territory and the emigration of remaining Jews left Poznań with almost only Polish people. In 1946, the population was 268,000. In the early post-war years, much of the city was rebuilt from the ruins. The city again became the capital of Poznań Voivodeship in the communist People's Republic of Poland.

In 1949, the 1572 Posnania asteroid was discovered at the Poznań Observatory and named after the city.

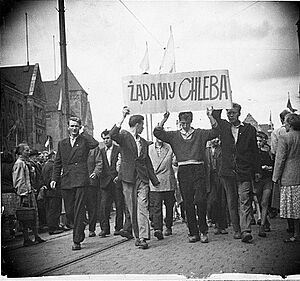

In June 1956, workers at the city's Cegielski factory protested low wages and food shortages. The government refused to talk. On June 28, a workers' march was fired upon by the authorities. The situation got worse; crowds attacked the communist party headquarters. According to official numbers, 67 people were killed, and hundreds were injured or arrested. The protests lasted two days until the army stopped them. These protests are seen as an early sign of resistance to communist rule in Poland. For more details, see Poznań 1956 protests.

From the 1960s, many new housing developments were built, mostly using pre-fabricated concrete blocks of flats. The largest areas for this were Rataje and Winogrady.

A major change in the city center in the late 1960s was rerouting the Warta river. Its main stream now flowed through a former flood relief channel. This made Ostrów Tumski a true island between two river branches. The old main stream was filled in, and a new main road was built across the island.

In 1975, Poznań became the capital of a much smaller Poznań Voivodeship.

After the success of the Solidarity movement, a monument to the events of June 1956 was built in 1981. Lech Wałęsa attended its unveiling. In 1983, Pope John Paul II visited Poznań.

In 1987, the city's boundaries expanded again, adding new areas mostly to the north.

After communism fell, the first free local government elections happened in 1990. A second papal visit took place in 1997. In 1998, a Weimar triangle meeting was held in Poznań with leaders from Germany, France, and Poland.

In 1997, transport improved greatly with the opening of the Poznań fast tram route (Poznański Szybki Tramwaj). Poznań got its first motorway connection in 2003, part of the A2 autostrada.

With the Polish local government reforms of 1999, Poznań again became the capital of a larger region, now called Greater Poland Voivodeship.

In 2006, Poland's first F-16 Fighting Falcons arrived in Poznań. They are stationed at the 31st Air Base in Krzesiny.

Poznań continues to host regular trade fairs and international events at the Poznań International Fair site. In December 2008, it hosted the United Nations Climate Change Conference. Poznań was also one of the host cities for the EuroBasket 2009 and 2012 European Football Championship.

In 2015, a medieval treasure, including 350 coins, was found during archaeological excavations in the Old Town.

See also

- History of Poland

- Historical population of Poznań

- Timeline of Poznań history

- Museum of the History of Poznań