History of St. Louis (1905–1980) facts for kids

The history of St. Louis, Missouri, from 1905 to 1980, saw big changes. The city's population and jobs decreased, especially after World War II. Even though St. Louis made improvements in the 1920s and cleaned up its air in the 1930s, more and more people moved to the suburbs. The city's population dropped a lot from the 1950s to the 1980s. Like many cities, St. Louis faced high unemployment during the Great Depression. Then, its factories grew during World War II. The city became home to Gateway Arch National Park (then called the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial) in the 1930s, and the famous Gateway Arch was built there in the 1960s. St. Louis City and St. Louis County tried many times to join their governments, but it didn't work out. The city also tried to fix old neighborhoods with new housing projects like Pruitt–Igoe, but people still kept moving to the county.

Contents

- Making St. Louis Better: Parks and Clean Air

- Segregation and the East St. Louis Riot

- St. Louis During World War I

- Jobs Between Wars and the Great Depression

- St. Louis During World War II

- Moving to the Suburbs and Losing People

- The Arch and Busch Stadium

- City Improvements and Housing Projects

- Attempts to Join City and County Governments

Making St. Louis Better: Parks and Clean Air

Starting in 1903, groups in St. Louis began building small parks and playgrounds. They wanted to give kids places to play in older neighborhoods. By 1909, St. Louis had 16 new parks! People like Charlotte Rumbold and Jane Addams helped with these efforts. The Parks Commissioner, Philip Scanlan, added baseball fields and tennis courts. His successor, Dwight F. Davis, continued this work, especially adding more tennis courts and a public golf course in Forest Park.

A zoo first opened in the 1870s, but it closed. Its animals went to collectors who kept them in Forest Park. In 1910, the St. Louis Zoological Society formed. They raised money to buy animals and asked the city to reopen a zoo. In 1913, Henry Kiel became mayor and supported the zoo idea. St. Louis gave 77 acres in Forest Park for the zoo. In 1916, people voted for a special zoo tax to keep it running. The zoo built its bear pits in 1919 with help from Carl Hagenbeck.

In 1923, St. Louis approved an $87 million bond issue for city improvements. This was the largest city debt issue in the country at the time! The money helped build new roads, parks, and hospitals. It also paid for Kiel Auditorium and Aloe Plaza downtown. Part of the money also started the St. Louis Gateway Mall, a long park stretching from the riverfront.

For many years, St. Louis had a big problem with coal smoke pollution. Even with rules against smoke, the air was still very dirty. By 1910, smoke was killing trees in Forest Park. In the 1920s, evergreen trees couldn't even grow near the city. Studies showed St. Louis had a huge amount of soot falling each year. The air was so bad that on November 28, 1939, the sky turned black during the day. This "smog" lasted for three weeks!

Finally, in December 1939, the city banned burning low-quality Illinois coal. This forced homes and businesses to use cleaner coal from Arkansas. The change was huge! In the winter of 1939–40, St. Louis had 177 hours of thick smoke. The next winter, it was only 17 hours. Also, the Laclede Gas Company started supplying natural gas in 1941. By the late 1940s, the smoke pollution problem was mostly solved.

Segregation and the East St. Louis Riot

After the Civil War, St. Louis didn't see as much racial violence as other Southern states. Most Black residents lived near the riverfront or railroads for work. City laws about segregation, called Jim Crow laws, were a bit mixed. Black people couldn't go into white hotels or restaurants. But they could use department store elevators with white people or sit in separate sections at theaters. Streetcar seating was even mixed. Before 1911, there were no laws forcing people to live in separate neighborhoods.

In the early 1910s, white neighborhoods near Black communities formed a group. They wanted a law to force segregation. The city government said no, but the group got enough signatures for a public vote in February 1916. The NAACP in St. Louis fought against this law. They said it was unfair and un-American. The mayor and most city leaders were against it, and local newspapers wrote articles opposing it.

Despite this, St. Louis voters strongly supported the segregation law. It was the first time such a law passed by public vote in the country. The law said no one could move onto a block where 75% of the people were of a different race. However, the NAACP filed a lawsuit, and a court stopped the law in April 1916. Later, the Supreme Court made this stop permanent. Even though the law was gone, private agreements called "restrictive covenants" started appearing. These agreements stopped white owners from selling homes to Black people.

Around this time, many African Americans began moving north in what was called the Great Migration. Thousands moved to East St. Louis, Illinois. They often found low-paying jobs, sometimes as strikebreakers. From June 30 to July 2, 1917, a terrible riot broke out in East St. Louis. A mob of white attackers, including police, destroyed many homes and hurt hundreds. Many Black people were killed. St. Louis City became a safe place during the riot. St. Louis police helped Black people cross the Eads Bridge to safety. The city government and the American Red Cross provided food and shelter.

Because of the riot and the Great Migration, St. Louis's Black population grew quickly from 1910 to 1920. However, St. Louis's overall population rank in the U.S. dropped from fourth to sixth.

St. Louis During World War I

When World War I started, the U.S. stayed neutral. But in St. Louis, people soon began supporting the Allies. Newspapers wrote articles against Germany. The German community in St. Louis held rallies for neutrality and raised money for German war widows. The Irish community also supported neutrality, mostly because they were against the British.

However, after the U.S. entered the war in April 1917, people in St. Louis became suspicious of Germans. Germans who were not U.S. citizens had to register as "enemy aliens." German-language newspapers were censored. High schools stopped teaching German. The St. Louis Symphony Orchestra stopped playing German music. The St. Louis Public Library even removed German books. Two city streets were renamed: Berlin Avenue became Pershing, and Van Verson Avenue became Enright.

Citizens also started reporting suspicious conversations. Several German immigrants were arrested under the Espionage Act of 1917. Some were freed, but others stayed in prison until the war ended. The war didn't greatly affect St. Louis businesses.

Jobs Between Wars and the Great Depression

After World War I, Prohibition made it illegal to sell alcohol. This hurt St. Louis's brewing industry a lot. Anheuser-Busch survived by selling malt syrup and a non-alcoholic drink called Bevo. Most other breweries closed. Other industries grew in the 1920s, like making shoes and clothes, electrical parts (by companies like Emerson Electric), and car parts. St. Louis had its own car brands, like Moon and Gardner, and assembly plants for Ford and General Motors. Tobacco processing was also a big industry. By 1929, St. Louis was seventh in the country for manufactured products.

By 1929, St. Louis had many different types of industries. The most important were food processing, chemical production, steelmaking, and making clothes and shoes. Industrial areas were easy to spot. North Broadway had lumber mills, Mallinckrodt Chemical, and meatpacking plants. South Broadway had heavy industries like Anheuser-Busch and Monsanto. West of downtown were railroad yards and tobacco factories. Downtown had lighter manufacturing, stores, banks, and insurance companies.

Even with its varied economy, St. Louis suffered a lot during the early years of the Great Depression. Factory production in St. Louis dropped by 57% between 1929 and 1933. By 1939, it was still only at 70% of its 1929 levels. When Prohibition ended in 1933, the brewing industry came back, which was good news. But it wasn't enough to make up for all the lost jobs.

| 1930 | 1931 | 1933 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National average | 8.7% | 15.9% | 24.9% |

| St. Louis (total) | 9.8% | 24% | 30% |

| St. Louis (whites) | 8.4% | 21.5% | 35% |

| St. Louis (blacks) | 13.2% | 42.8% | 80% |

Unemployment was very high in cities during the Depression, and St. Louis was no different (see table). Black workers faced much higher unemployment. They were often fired and replaced by white workers, especially after minimum wage laws started in the mid-1930s. In factories, Black workers lost jobs first. Many Black people working in domestic service were only paid with a place to live and food. Skilled Black workers couldn't join unions and were shut out of construction jobs. Despite this unfairness, Black residents received fair amounts of relief aid. After 1933, Black people in the city mostly voted for the Democratic Party, changing from their past support of the Republican Party.

From 1930 to 1932, St. Louis spent $1.5 million on relief efforts. Groups like the Salvation Army and the St. Vincent de Paul Society gave another $2 million. In late 1932, St. Louis voters approved a $4.6 million bond to help more. In 1933, Mayor Bernard Dickmann and the city council cut spending to balance the budget. Federal relief programs started sending money in May 1933. St. Louis issued another bond for relief in 1935 for $3.6 million. Most of the money for relief in St. Louis came from the federal government.

New Deal programs, like the Public Works Administration, hired thousands of St. Louisans. Money from civic improvement bonds for airport construction also helped lower unemployment. Another bond in 1934 paid for city beautification and building renovations. This reduced the number of people needing direct relief from over 100,000 in 1933 to 35,000 in 1936.

St. Louis During World War II

After the attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan in 1941, St. Louis began preparing for possible attacks. Soldiers protected local military sites like the St. Louis Army Ammunition Plant and Lambert Field. Police protected bridges. Factory workers were checked for safety. German, Italian, and Japanese people, even citizens, were questioned or arrested. Some Japanese restaurants closed. The FBI made arrests in St. Louis for people accused of speaking against the war.

People worried about a Japanese air raid, even though St. Louis was far from the coasts. At first, the city had no air raid sirens. City leaders spent $50,000 on defense, including lighting the MacArthur Bridge. Radio shows were canceled, and weather forecasts were kept secret. Civil defense preparations were slow, but on March 7, 1942, the city had its first blackout. A second blackout in 1943 was much better. The local Office of Civilian Defense signed up thousands of air raid wardens, firefighters, and police volunteers. City inspectors chose 200 sites as air raid shelters for 40,000 people. Schools prepared students for attacks. Anti-aircraft guns protected the area, but they sometimes accidentally fired on civilian planes.

St. Louis factories started preparing for war in 1940. The government ordered $16 million in planes from Curtiss-Wright. A $14 million order for explosives led to a new factory in Weldon Spring, Missouri. The biggest war plant was the U.S. Cartridge ammunition factory in north St. Louis. At its busiest, it employed over 35,000 people and made over a billion rounds of ammunition a year! Monsanto switched entirely to war production, making chemicals for TNT and medicines. By the end of the war, over 75% of St. Louis factories were doing defense work. They made weapons, uniforms, food, and medical drugs. The uranium for the Manhattan Project (which built the atomic bomb) was refined in St. Louis by Mallinckrodt Chemical Company. In 1944, the St. Louis Chevrolet factory started making DUKWs (amphibious vehicles) for the invasion of Normandy.

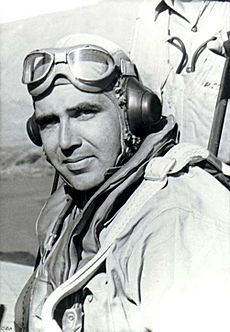

Many brave soldiers came from St. Louis during the war. Edward O'Hare grew up in St. Louis. In 1942, he shot down five Japanese bombers attacking the USS Lexington. He received the Medal of Honor and had a parade in St. Louis. Wendell O. Pruitt, an African-American pilot, shot down three enemy planes in 1944. St. Louis celebrated him with "Captain Wendell O. Pruitt Day." More than 5,400 St. Louisans were killed or went missing in the war.

Things like rubber (especially tires) were rationed in St. Louis starting in 1942. The St. Louis Rationing Board controlled tire sales. Most tires went to emergency vehicles. Stores stopped home deliveries, and high schools canceled spring sports because of no tires for travel. Sugar rationing followed in May, and gasoline was limited in the fall of 1942. Scrap drives were common. In 1943, people even tried to dig up the old ferris wheel from the 1904 World's Fair for scrap metal. Meat and dairy were also in short supply. St. Louis was the first U.S. city to reach its war bond goals in 1942 and 1943.

During the war, African Americans found more jobs in factories. By the end of 1942, nearly 8,000 Black men and women were hired in St. Louis industries. However, job discrimination was still a big problem. Most factory jobs were unskilled. In April 1943, Rev. Jasper C. Caston became the first African American elected to the St. Louis Board of Aldermen. Clara Hempelmann was the first woman elected to the Board in the same election.

The war also led to the first city integration law in March 1944. It allowed African Americans to eat at city-owned lunch counters, but not private ones. In May 1944, a Black sailor was refused service. In response, the Citizens Civil Rights Committee of St. Louis organized a sit-in at a drugstore lunch counter. Protesters were removed. Sit-ins at other stores also happened. These protests didn't immediately change Jim Crow laws at lunch counters. However, Saint Louis University admitted its first Black students in the fall of 1944.

In 1943, hundreds of German prisoners of war were held in St. Louis. Thousands of Italians were held in Weingarten, Missouri. These prisoners helped fill sandbags during Mississippi River floods in May 1943. Flooding still caused problems in north St. Louis. Also in 1943, St. Louis Mayor William D. Becker and ten others died in a glider accident. His replacement, Aloys Kaufmann, was the last Republican mayor until 2009.

When the war in Europe ended on Victory in Europe Day, many St. Louis war factories closed. The Red Cross and Office of Civil Defense started laying off workers. Nearly 20,000 defense workers lost their jobs within a week. U.S. Cartridge laid off 4,000 workers, and Curtiss-Wright laid off 11,000. Returning soldiers found St. Louis had a shortage of housing and jobs. When Japan surrendered in August 1945, $250 million in war contracts were canceled in St. Louis. 80,000 St. Louisans lost their jobs immediately, causing temporary economic problems. One of the biggest and longest-lasting effects of the war was the GI Bill. This law helped veterans buy homes in St. Louis County, causing many people to move out of St. Louis City.

Moving to the Suburbs and Losing People

| Population of St. Louis City |

||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1900 | 575,238 | — |

| 1910 | 687,029 | +19.4% |

| 1920 | 772,897 | +12.5% |

| 1930 | 821,960 | +6.3% |

| 1940 | 816,048 | −0.7% |

| 1950 | 856,796 | +5.0% |

| 1960 | 750,026 | −12.5% |

| 1970 | 622,236 | −17.0% |

| 1980 | 452,801 | −27.2% |

| 1990 | 396,685 | −12.4% |

| 2000 | 348,189 | −12.2% |

| 2010 | 319,294 | −8.3% |

| Source: | ||

People moving westward from St. Louis City had been happening for a long time, but it sped up in the early 1900s. German Jewish immigrants moved to wealthy areas in west St. Louis. Eastern European Jewish immigrants moved to northwest St. Louis and towns like Wellston and University City, Missouri. Italians first lived in a "Little Italy" near downtown. But in the 1910s and 1920s, many Italians moved to The Hill, an area west of Kingshighway. This area was far enough from the city that they kept their culture. After World War II, The Hill declined, but it was revived in 1969 and is still a symbol of Italian-American culture in St. Louis.

Starting in the 1890s, a large streetcar system and train stations made it easy to travel from suburban towns into downtown St. Louis. Towns like Kirkwood, Maplewood, and Clayton grew quickly between 1900 and 1930. Many people moving to these towns caused St. Louis County's population to double from 1910 to 1920. St. Louis City only grew by 12% in the same time. In the 1930s, St. Louis City's population dropped a little for the first time, but St. Louis County grew by almost 30%. Most new buildings in the region were outside city limits in the late 1930s. St. Louis planners couldn't stop this by adding more land to the city.

More people owning cars after World War II also made it easier to move far from the city. St. Louis City reached its highest population in the 1950 census. This was because there was a housing shortage after the war. But continued suburban growth and new highways led to a big drop in the city's population over the next few decades. Between 1950 and 2000, the city lost more than half its people to St. Louis County and St. Charles County. Some people even left the region entirely. This was part of a national trend where jobs and people moved away from older industrial cities in the Midwest to growing cities in the south and west.

The Arch and Busch Stadium

Early efforts to improve St. Louis neighborhoods happened at the same time as plans for a riverfront memorial to honor Thomas Jefferson. This memorial would later include the famous Gateway Arch. In the early 1910s, St. Louis businessman Luther Ely Smith wanted to fix up the riverfront. He wanted more green spaces and better living conditions near the docks. In 1933, Mayor Bernard Dickmann formed a group to promote Smith's idea as both a renewal project and a memorial. This worked, and in 1934, Congress created a commission to plan the project.

The commission approved a plan to clear land south of the Eads Bridge. This area would cover the original village of St. Louis. In 1935, the city issued a $7.5 million bond to buy and tear down buildings in the area. The Works Progress Administration helped with $9 million. Work began quickly to clear the forty-block area. The only part of the old street grid that remained was north of the Eads Bridge (now Laclede's Landing). The only building left in the area was the Old Cathedral, built in 1834. Demolition continued until World War II. Then, the area became a parking lot, and the project stopped until the late 1940s.

Luther Ely Smith again led the effort for the riverfront project in 1945. His group held a design competition for the memorial. In 1948, Eero Saarinen's design, the Gateway Arch, won. But construction didn't start until 1954, with $5 million from Congress. In the 1950s and 1960s, the federal government gave almost $20 million more to finish the project. Money also came from other groups and a 1967 city bond. The Arch was completed in October 1965. A museum and visitors' center opened underneath it in 1976. The Arch attracted millions of visitors and led to over $500 million in downtown construction in the 1970s and 1980s.

Starting in the 1920s, the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team became more popular than the older St. Louis Browns. Both teams shared Sportsman's Park. The Cardinals, with players like Rogers Hornsby, won their first World Series in 1926, beating the New York Yankees. The Cardinals won more championships in the 1930s and 1940s. As the Cardinals won, the Browns lost fans. The Browns only won their league once, in 1944, but lost to the Cardinals in the 1944 World Series. In 1953, the Browns' owner sold Sportsman's Park to the Cardinals. The Browns team moved and became the Baltimore Orioles.

By the mid-1950s, Sportsman's Park needed expensive repairs. A new park was proposed closer to downtown. The new park's design, by Edward Durell Stone, looked like the Gateway Arch. The Cardinals moved into Busch Memorial Stadium for the 1965 season. However, building the stadium meant tearing down Chinatown, St. Louis, ending decades of a Chinese community there. The stadium was very hot in summer, but it was much bigger and helped downtown development.

City Improvements and Housing Projects

At the same time as plans for Gateway Arch National Park in the 1930s, there were also plans for low-rent housing for the city's poor. Many infant deaths and tuberculosis cases came from small, crowded neighborhoods. To fix this, the city built two housing projects between 1939 and 1942. Carr Square Village was in the north, and Clinton-Peabody Terrace was near City Hospital. They cost $7 million and had over 1,300 units. Even with these projects, after World War II, over 33,000 houses in St. Louis still shared toilets or had outdoor ones. Thousands lived in very cramped and dirty conditions.

Under Mayor Joseph Darst, in 1953, the St. Louis Land Clearance Reutilization Authority (LCRA) bought and cleared the old Chestnut Valley area. They then sold the land to developers who built middle-class apartment buildings called Plaza Square. That same year, Darst supported a $1.5 million bond to finish the St. Louis Gateway Mall project. Darst also encouraged building several large high-rise housing projects, which all started between 1951 and 1953.

The first project, Cochran Gardens, opened in 1953. It had over 700 units in several buildings. Another project, Darst-Webbe, opened in 1956 with over 1,200 units. The most famous and largest project was Pruitt–Igoe, which opened in 1954 and 1955. It had 33 eleven-story buildings with nearly 3,000 units. Minoru Yamasaki, who later designed the World Trade Center, designed Pruitt-Igoe. East of Pruitt-Igoe was the Vaughn Apartments complex with over 650 units. Between 1953 and 1957, St. Louis gained over 6,100 public housing units. Everyone was excited when they opened.

However, the projects had problems from the start. Gangs attacked residents at Darst. There wasn't enough space for recreation, healthcare, or shopping. Jobs were hard to find. Crime was a big problem, especially at Pruitt-Igoe. Even after a $5 million renovation in 1965, only 17 of 33 Pruitt-Igoe towers had people living in them by 1971. Thieves stole plumbing, causing waste to build up in hallways. Two Pruitt-Igoe buildings were torn down for playgrounds in 1972. But problems continued, and the other 31 towers were demolished in 1975. The other St. Louis housing projects stayed mostly full through the 1980s, despite ongoing crime issues.

Along with the housing projects, a 1955 bond issue for over $110 million helped build three expressways into downtown St. Louis. These included the Daniel Boone Expressway (now Interstate 64), the Mark Twain Expressway (now Interstate 70), and the Ozark Expressway (now Interstate 44). A highway bridge over the Mississippi was also planned. In 1967, the Poplar Street Bridge opened, connecting all three expressways over the river.

The 1955 bond issue also paid for clearing over 450 acres of a neighborhood called Mill Creek Valley, starting in 1959. Nearly 2,000 families and over 600 individuals had to move. This land was used for the Daniel Boone Expressway, new industrial sites, and an expansion of Saint Louis University. Most of the people who moved were poor Black residents. The NAACP called it a "Negro Removal Project." They were moved to housing projects and historically stable Black neighborhoods like The Ville. Middle-class Black residents moved west to north St. Louis County. This made social problems worse in north St. Louis. Although some subsidized housing was built in Mill Creek Valley in the 1960s, the area didn't meet expectations by the late 1970s.

Attempts to Join City and County Governments

Because so many people were moving out of St. Louis City, leaders tried several times to combine city and county governments or services. One early attempt was in 1926. A state law allowed a group to create a plan for the city to take over all of St. Louis County. City voters approved it, but county voters rejected it. A 1930 law to combine only some services also failed, mostly because county voters said no. More efforts to combine services were made only after World War II.

One of the few successful attempts was the creation of the Metropolitan Sewer District in 1954. This was a city-county water and sewer company. However, the next year, voters rejected a city-county transit agency. This led St. Louis Alderman Alfonso J. Cervantes to suggest a meeting to discuss combining the city and county.

Mayor Raymond Tucker got money to study consolidation. The study found that most people in the county and city wouldn't support a full merger. But they would support combining some agencies, like public transportation, zoning, and property assessment. The group that met chose these recommendations to present to voters. They decided against a full city-county merger. Most major business groups, unions, and Cervantes supported the idea. But Mayor Tucker refused to support it, saying it wasn't enough. Arguments against creating a new government district also worked. Both city and county voters rejected the plan.

As St. Louis County's population grew, many small towns and cities formed. By the 1960s, there were over 90 separate towns! People who wanted regional planning had some success in 1965. They created the East-West Gateway Coordinating Council. This council could help cities in the region apply for federal money. One controversial idea from this council was to build a second regional airport in Illinois. The plan was approved in 1976. But in 1977, Secretary of the Interior Brock Adams canceled the airport project. This was due to pressure from Missourians who worried about losing business at Lambert International Airport.

|