History of Sunderland facts for kids

Sunderland is a city in England with a long and interesting history. It got its name from a word meaning "separate land." Back in 685 AD, a king named Ecgfrith gave a piece of land, a "sunder-land," to a monk named Benedict Biscop. Around the same time, a famous scholar called The Venerable Bede moved to a nearby monastery. He wrote that he was born in the "sundorlande" of that monastery. This might mean he was born in a "separate land" or in the area that later became Sunderland.

Contents

Early History of Sunderland

People have lived in the Sunderland area for a very long time, even since the Stone Age. These early people were hunter-gatherers. Tools from this time have been found near St Peter's Church, Monkwearmouth. During the later Stone Age, around 4000 to 2000 BC, Hastings Hill was an important place for burials and special ceremonies.

Roman Times in Sunderland

Before and during the Roman Empire, the Brigantes tribe lived around the River Wear. There's a local story that the Romans had a settlement on the south side of the River Wear, where the old Vaux Brewery used to be. However, no one has dug there to find out for sure.

In 2021, some exciting Roman objects were found in the River Wear near North Hylton. These included four stone anchors! This discovery is very important and might mean there was a Roman dam or port on the River Wear.

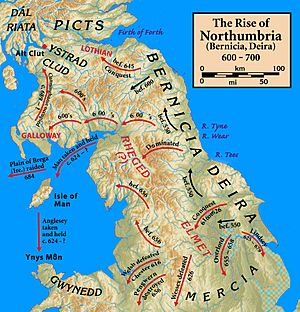

Anglo-Saxon Northumbria

The first recorded settlements at the mouth of the River Wear date back to 674 AD. An Anglo-Saxon nobleman, Benedict Biscop, was given land by King Ecgfrith of Northumbria. He built the Wearmouth–Jarrow (St Peter's) monastery on the north side of the river. This area became known as Monkwearmouth.

Biscop's monastery was the first in Northumbria to be built from stone. He brought glaziers from France, which helped bring glass making back to Britain. In 686, Ceolfrid took over the monastery. Wearmouth–Jarrow became a major center for learning in Anglo-Saxon England, with a library of about 300 books.

The Codex Amiatinus, a very famous and beautiful book, was created at this monastery. It's likely that Bede worked on it. Bede was born near Wearmouth in 673. He wrote an important book called The Ecclesiastical History of the English People in 731. This book earned him the title "The father of English history."

In the late 700s, Vikings raided the coast. By the mid-800s, the monastery was empty. In 930, land on the south side of the river was given to the Bishop of Durham. This area became known as Bishopwearmouth and included places like Ryhope, which are now part of Sunderland.

Medieval Sunderland

Around 1100, a fishing village called 'Soender-land' (which became Sunderland) was part of Bishopwearmouth parish. In 1179, Hugh Pudsey, the Bishop of Durham, gave this settlement a special charter. This charter gave its merchants the same rights as those in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

At first, fishing was the main business, mostly herring and later salmon. By 1346, shipbuilding began on the Wear. By 1396, a small amount of coal was being sent out from the port.

The port grew quickly because of the salt trade. Salt had been exported from Sunderland since the 1200s. In 1589, salt pans were built at Bishopwearmouth Panns. Here, large vats of seawater were heated with coal to make salt. This need for coal helped a coal mining community grow. Only poor-quality coal was used for salt, so better coal was traded through the port, which then grew even more.

Sunderland in the 1600s

Both salt and coal continued to be exported in the 1600s. The coal trade grew a lot, from 2-3,000 tons in 1600 to 180,000 tons by 1680. Because the River Wear was shallow, coal from further inland was loaded onto keels (large, flat-bottomed boats). These boats took the coal downriver to bigger ships. The people who worked on these keels were called 'keelmen'.

In 1634, a new charter was given to Sunderland, making it a borough with a mayor and aldermen. However, this didn't last long because of the English Civil War.

During the Civil War, Sunderland and Newcastle were on opposite sides. Parliament blocked the River Tyne, which hurt Newcastle's coal trade. This allowed Sunderland's coal trade to do very well for a short time.

After the war, in 1669, King Charles II allowed a pier and lighthouse to be built in Sunderland to improve the harbor. It took some time for these improvements to happen. More shipbuilders also started working on the River Wear in the late 1600s.

Sunderland in the 1700s

River Improvements

The River Wear Commission was set up in 1717 as Sunderland's port grew. They worked to make the river better for ships. Their first big project was building the South Pier in 1723 to help guide the river channel. This pier was finished in 1759. By 1748, the river was being cleaned by hand. Later, a more permanent North Pier was started in 1786. It had a wooden frame filled with stones and was covered with masonry. A lighthouse was built at its end in 1794.

By the early 1700s, many small shipyards lined the River Wear. After 1717, with the river made deeper, Sunderland's shipbuilding grew a lot. Many warships and commercial sailing ships were built. By the mid-1700s, Sunderland was probably the top shipbuilding center in Britain. By 1788, it was Britain's fourth-largest port by ship size. It was also the main coal exporter.

Sunderland's third-biggest export, after coal and salt, was glass. The first modern glassworks opened in the 1690s. The industry grew because ships brought good sand (used as ballast) from places like the Baltic Sea. This sand, along with local limestone and coal, was key for glassmaking. Other industries that grew along the river included lime burning and pottery making.

The world's first steam dredger was built in Sunderland in 1796-97. It was used to deepen the river. It used a 4-horsepower steam engine. In 1797, the world's first factory for machine-made rope was built in Sunderland. It used a steam-powered machine invented by a local schoolmaster. This ropery building still stands today.

City Growth

In 1719, a new church, Holy Trinity Church, Sunderland, was built. This created a new parish for the busy east end of Bishopwearmouth. Later, in 1769, St John's Church was built. By 1720, the port area was fully built up with houses and factories. The three original settlements of Wearmouth (Bishopwearmouth, Monkwearmouth, and Sunderland) started to join together because of the port's success. Around this time, Sunderland was known as 'Sunderland-near-the-Sea'.

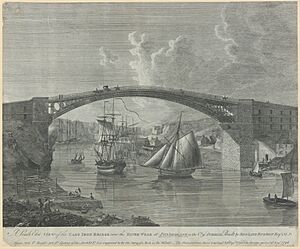

By 1770, Sunderland had grown westwards along its High Street to meet Bishopwearmouth. In 1796, Bishopwearmouth connected with Monkwearmouth when the Wearmouth Bridge was built. This was the world's second iron bridge. It was a huge success for engineering and was very elegant. It was the biggest single-span bridge in the world at the time.

Defences

During the War of Jenkins' Ear, two gun batteries were built in 1742 and 1745 to protect the river from attacks. One was washed away, but the other was made bigger during the French Revolutionary Wars and became known as the Black Cat Battery. In 1794, Sunderland Barracks were built behind the battery.

Sunderland in the 1800s

In 1802, a new stone lighthouse was built on the North Pier. At the same time, a lighthouse was built on the South Pier. It showed a red light when the tide was high enough for ships to enter the river. In 1840, work began to make the North Pier even longer. Its lighthouse was moved in one piece to the new end, staying lit every night!

Coal, Docks, and Railways

In the early 1800s, important coal mine owners included Lord Durham and the Marquis of Londonderry. In 1822, the Hetton colliery railway opened. It linked coal mines to the riverside at Bishopwearmouth, where coal was dropped directly into ships. This was the first railway in the world to run without animal power.

People worried that Sunderland needed a proper dock to keep up with other ports. Sir Hedworth Williamson started the Wearmouth Dock Company in 1832. He even asked famous engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel for designs. The North Dock opened in 1837, but it was too small and didn't have a direct rail link to the coal mines on the south side of the river.

Meanwhile, in Monkwearmouth, a coal mine called Wearmouth Colliery started digging in 1826. In 1835, it began producing coal. When a better coal seam was found in 1846, it became very profitable. At one point, it was the deepest mine in the world.

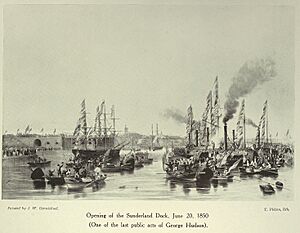

South of the river, the Durham & Sunderland Railway opened in 1836. In 1846, the Sunderland Dock Company was formed to build a new dock. This dock, later called Hudson Dock, opened on June 20, 1850. Most of the dockside was used for coal, but there was also a warehouse.

From 1850 to 1856, a sea entrance was built at the south-east corner of Hudson Dock. This allowed larger ships to enter directly from the North Sea. Hudson Dock was also made bigger and deeper. In 1859, the docks were bought by the River Wear Commissioners. They built Hendon Dock to the south (1864–67). Lock gates and a swing bridge were added to the river entrance in 1875, allowing ships to enter at any tide.

By 1889, two million tons of coal passed through the dock each year. The eastern parts of the docks had sawmills and timber yards. Other industries also grew, like the Wear Fuel Works, which made pitch and oil from coal tar.

As industries grew, richer people moved away from the old port area to new suburbs. Fawcett Street became the town center. In 1848, a train station, Monkwearmouth Station, was built north of Wearmouth Bridge. Another station was built in Fawcett Street in 1853. The Wearmouth Railway Bridge opened in 1879, allowing trains to cross the river. Sunderland Town Hall was built in Fawcett Street between 1886 and 1890.

"The Greatest Shipbuilding Port in the World"

Sunderland's shipbuilding industry grew throughout most of the 1800s. It became the town's most important industry. By 1815, Sunderland was the top port for building wooden trading ships. In 1840, the town had 76 shipyards. From 1846 to 1854, almost a third of all UK ships were built in Sunderland! In 1850, the Sunderland Herald newspaper called the town "the greatest shipbuilding port in the world."

During the 1800s, ships became bigger, and new technologies were used. In 1852, the first iron ship was launched on the Wear. Thirty years later, ships were being built with steel. As the century went on, there were fewer shipyards, but they became much larger to build bigger and more complex ships.

Many important shipyards were founded in the 1800s, including Sir James Laing & Sons, S. P. Austin, Bartram & Sons, and William Doxford & Sons.

Marine engineering works also started in the 1820s, making engines for steamships. Even with steam power, sailing ships were still built, including fast clippers like the City of Adelaide (1864) and Torrens (1875).

Other Industries

By the mid-1800s, glassmaking was at its peak in Sunderland. James Hartley & Co. became the largest glassworks in the country. They made much of the glass for the famous the Crystal Palace in 1851. Other glass factories made pressed glass and bottles.

Local potteries also did well in the mid-1800s, using clay and stone brought in by ships. Sunderland pottery was sold across Europe. However, the industry declined later in the century because of competition from other countries.

Victoria Hall Disaster

The Victoria Hall was a large concert hall in Sunderland. On June 16, 1883, a terrible tragedy happened there when 183 children died. During a show, children rushed towards a staircase to get treats. At the bottom of the stairs, a door had been opened inwards and bolted, leaving only a small gap. The children pushed down the stairs, and those at the front were trapped and crushed by the crowd behind them.

The death of 183 children, aged three to 14, was the worst disaster of its kind in British history. A memorial, showing a grieving mother holding a dead child, is in Mowbray Park. This event led to new laws requiring public buildings to have a minimum number of emergency exits that open outwards. This law is still in place today. Victoria Hall was later destroyed by a German bomb in 1941.

Lyceum Theatre

The Lyceum was a public building on Lambton Street, opened in 1852. It had many rooms, including a hall that became a theatre in 1854. It burned down in 1855 but was rebuilt and reopened in 1856 as the Royal Lyceum Theatre. This theatre was where famous actor Henry Irving had his first successes. The building burned down again in 1880 and was demolished.

Sunderland in the 1900s and 2000s

Sunderland's public transport improved between 1900 and 1919 with an electric tram system. These trams were slowly replaced by buses in the 1940s and stopped completely in 1954. In 1909, the Queen Alexandra Bridge was built, connecting Deptford and Southwick.

The First World War led to more shipbuilding, but Sunderland was also attacked by a Zeppelin in 1916. The Monkwearmouth area was hit, and 22 people died. Many citizens also served in the armed forces during this time.

After the First World War and during the Great Depression of the 1930s, shipbuilding declined a lot. The number of shipyards on the Wear went from fifteen in 1921 to just six in 1937.

When World War II started in 1939, Sunderland was a key target for the German Luftwaffe. Bombs killed 267 people, damaged or destroyed 4,000 homes, and badly hurt local industries. After the war, more houses were built. Sunderland's boundaries grew in 1967 to include nearby towns like Ryhope and Silksworth.

In the second half of the 1900s, shipbuilding and coal mining declined. Shipbuilding ended in 1988, and coal mining stopped in 1993. At one point in the mid-1980s, up to 20 percent of the local workers were unemployed.

As the old heavy industries closed, new ones started, including electronics, chemicals, paper, and car manufacturing. The service industry also grew. In 1986, the Japanese car company Nissan opened its Nissan Motor Manufacturing UK factory in Washington. It is now the UK's largest car factory.

From 1990 onwards, the banks of the River Wear were redeveloped. Old shipbuilding sites became homes, shops, and business centers. The University of Sunderland built a new campus at the St Peter's site, next to the National Glass Centre.

Sunderland officially became a city in 1992. Like many cities, it includes several areas with their own histories, such as Fulwell, Monkwearmouth, Roker, and Southwick on the north side of the Wear, and Bishopwearmouth and Hendon to the south. On March 24, 2004, the city chose Benedict Biscop as its patron saint.

In the 1900s, Sunderland A.F.C. became very famous for sports in the area. The football club was founded in 1879 by a schoolmaster named James Allan. Sunderland joined The Football League in 1890. By 1936, they had won the league championship five times. They won their first FA Cup in 1937. Their only major win after World War II was a second FA Cup in 1973.

After 99 years at the historic Roker Park stadium, the club moved to the 42,000-seat Stadium of Light in 1997. At the time, it was the largest stadium built by an English football club since the 1920s. It has since been made even bigger to hold almost 50,000 fans.

In 2018, Sunderland was named the best city to live and work in the UK by a finance company. It was also ranked as one of the top 10 safest cities in the UK that same year.

Many beautiful old buildings still stand in Sunderland, even after the bombing during World War II. These include Holy Trinity Church (built in 1719), St Michael's Church (now Sunderland Minster), and St Peter's Church, Monkwearmouth, which has parts dating back to 674 AD. St Andrew's Church, Roker is known for its beautiful art and crafts. St Mary's Catholic Church is the oldest surviving Gothic revival church in the city.

The Sunderland Civic Centre was opened in 1970. It closed in 2021 when a new City Hall opened on the site of the old Vaux Brewery.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |