History of Venezuela facts for kids

The history of Venezuela tells the story of this South American country. It begins with the native people who lived here long before Europeans arrived. These groups, like the Timoto-Cuica people in the Andes, had their own complex societies.

In 1498, Christopher Columbus sailed along Venezuela's coast. Soon after, Spanish explorers began to arrive. From 1528 to 1546, a German banking family, the Welser, even had control of a part of Venezuela, calling it "Klein-Venedig" (Little Venice). They were looking for a legendary golden city called El Dorado. During this time, cities like Maracaibo and Coro were founded.

After the Germans left, Spain took full control. The city of Caracas was founded and became an important capital. The economy in the early colonial times focused on gold mining and raising livestock. Later, cocoa plantations became very important, worked by enslaved Africans.

Venezuela was part of larger Spanish territories until it became the Captaincy General of Venezuela in 1777. In 1811, it was one of the first Spanish colonies in America to declare independence. However, it took until 1821 for independence to be truly won. Venezuela then joined a larger republic called Gran Colombia. In 1830, it became a fully independent country.

The 19th century was a time of political struggles and strong military leaders called caudillos. This continued until the mid-20th century. Since 1958, Venezuela has had democratic governments. But in the 1980s, economic problems led to protests and political changes. In 1998, Hugo Chávez was elected president, starting the "Bolivarian Revolution." A new constitution changed the country's name to the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. More recently, Venezuela has faced a serious economic and social crisis.

Contents

Ancient Venezuela

Scientists have found signs of the first people in Venezuela. They found tools made from stone that are very old, dating back about 15,000 to 9,000 years ago. These early groups hunted large animals like giant sloths and armadillos. Over time, they started to find other food sources and formed early tribes.

Before Europeans arrived, about one million people lived in Venezuela. This included groups like the Caribs and the Timoto-Cuicas. The Timoto-Cuica people had the most advanced society. They lived in planned villages with irrigated fields and water storage. Their homes were made of stone and wood. They were mostly peaceful farmers, growing crops like potatoes. They also made beautiful ceramic art. They are even believed to have invented the arepa, a popular Venezuelan food today.

When the Spanish began to arrive in the 16th century, the number of native people, like the Mariches, decreased. Native leaders, called caciques, such as Guaicaipuro and Tamanaco, tried to fight against the Spanish. But the Spanish eventually defeated them.

Spanish Rule in Venezuela

In 1498, Christopher Columbus sailed along the eastern coast of Venezuela. He discovered the "Pearl Islands" of Cubagua and Margarita. Spanish explorers later returned to these islands to collect valuable pearls. They enslaved the native people to harvest the pearls. These pearls became a very important resource for Spain between 1508 and 1531.

In 1499, another Spanish expedition, led by Alonso de Ojeda, sailed along the northern coast. They named the area Venezuela, meaning "little Venice" in Spanish. This was because they saw native houses built on stilts over the water, which reminded them of Venice, Italy.

Spain began to settle the mainland of Venezuela in 1502. The first permanent Spanish settlement in South America was in what is now the city of Cumaná. When the Spanish arrived, native people lived as farmers and hunters along the coast, in the Andes mountains, and near the Orinoco River.

German Control: Klein-Venedig

From 1528 to 1546, a German banking family from Augsburg, the Welser family, controlled a large part of Venezuela. This was called Klein-Venedig (Little Venice). The Spanish king, Charles I, gave them these rights because he owed them money. The main goal of the Germans was to find the legendary golden city of El Dorado.

The first leader of this venture was Ambrosius Ehinger, who founded Maracaibo in 1529. After Ehinger and his successor died, Philipp von Hutten continued exploring inland. While he was away, the Spanish king took back the right to appoint the governor. When Hutten returned in 1546, the Spanish governor had him executed. The king then ended the Welser family's control.

Colonial Economy and Society

By the mid-16th century, only about 2,000 Europeans lived in Venezuela. In 1632, gold mines opened in Yaracuy. This led to the start of slavery, first of native people, and then of Africans brought from Africa. The colony's first real economic success came from raising livestock on the grassy plains called Llanos. This created a society with a few Spanish landowners and many native herdsmen.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the cities in Venezuela were not very important to Spain. The main Spanish centers in America, like Mexico and Peru, were more interested in their rich gold and silver mines. Venezuela's control shifted between these larger territories.

In the 18th century, a new society grew along the coast. Large cocoa plantations were created, worked by many more enslaved Africans. Many enslaved Black people also worked on farms in the llanos. Most of the native people who survived moved south into the plains and jungles. There, Spanish monks, especially the Franciscans, worked with them.

Growth and Education

The Province of Venezuela became part of the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1717. In 1777, it became the Captaincy General of Venezuela. A company called the Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas had a strong control over trade with Europe. This company helped Venezuela's economy grow, especially by encouraging the farming of cacao beans. Cocoa became Venezuela's main export.

Caracas also became a center for learning. From 1721, it had its own university. It taught subjects like Latin, medicine, and engineering. One of its most famous graduates was Andrés Bello, a brilliant scholar. In a town near Caracas, a music school also thrived. The growth of education helped improve society.

Venezuelan Independence

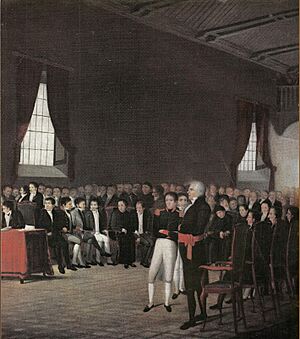

News of Spain's problems during the Napoleonic Wars in Europe reached Caracas in 1808. On April 19, 1810, the city council decided to follow Spain's example and set up its own government. On July 5, 1811, seven of Venezuela's ten provinces declared their independence. This created the First Republic of Venezuela.

However, the First Republic fell in 1812 after a big earthquake in Caracas and a battle. Simón Bolívar then led a campaign to take back Venezuela, creating the Second Republic of Venezuela in 1813. But this also did not last, as Spanish forces and local uprisings defeated it. Venezuela finally achieved lasting independence from Spain in 1821. This was part of Bolívar's larger effort to free New Granada (modern-day Colombia).

On December 17, 1819, a meeting in Angostura declared Gran Colombia an independent country. Venezuela, along with Colombia, Panama, and Ecuador, was part of Gran Colombia until 1830. In 1830, Venezuela became a separate, independent country.

The First Republic: A New Beginning

By the late 1700s, some Venezuelans wanted to be free from Spanish control. Spain had not paid much attention to its Venezuelan colony. This allowed Venezuelan thinkers to learn more about new ideas. The wealthy white elite, called mantuanos, had access to good education. They were often proud and wanted to keep their special rights, even against the mixed-race majority.

In 1797, the first organized plan against colonial rule happened. It was led by Manuel Gual and José María España. It was inspired by the French Revolution. But the mantuanos helped stop it because it called for big social changes.

Events in Europe also helped Venezuela declare independence. The Napoleonic Wars weakened Spain's power. In 1808, Napoleon took over Spain and made his brother king. This started Spain's own war for independence from France.

News of Spain's troubles reached Caracas. On April 19, 1810, the city council decided to form its own government. Other cities followed. Some mantuanos, including 27-year-old Simón Bolívar, saw this as a step towards full independence. On July 5, 1811, seven of Venezuela's ten provinces declared their independence.

This led to the Venezuelan War of Independence. The First Republic of Venezuela ended in 1812 after a major earthquake in Caracas and a defeat in battle.

The Second Republic and Bolívar's Campaigns

Bolívar went to Cartagena and Bogotá, where he joined the army of New Granada. He gathered a force and invaded Venezuela in 1813, crossing the Andes mountains. His main helper was José Félix Ribas. In Trujillo, Bolívar issued his famous "Decree of War to the Death." He hoped this would make more people join his side.

At the same time, Santiago Mariño and Manuel Piar were fighting Spanish loyalists in eastern Venezuela. Bolívar took Caracas and re-established the Republic on August 6, 1813. But a strong leader from the plains, José Tomás Boves, started a movement against the Republic. Bolívar and Ribas were defeated by Boves in 1814. Republicans had to leave Caracas and flee. Bolívar left Venezuela again and went to New Granada in 1815.

Gran Colombia and Final Independence

In 1820, a new government in Spain meant no more Spanish invasions of America. A truce was signed between Spanish general Morillo and Bolívar. The truce ended in 1821. Bolívar gathered his forces to face the Spanish in the Battle of Carabobo. The Spanish were defeated in this key battle, thanks in part to British soldiers helping the independence forces.

After Carabobo, a meeting in Cúcuta approved a new constitution for Gran Colombia. Other battles followed, including a naval victory in the Battle of Lake Maracaibo in 1823. In November 1823, the last Spanish stronghold in Venezuela fell.

Venezuela Becomes a Separate Country

Venezuela was a province of Gran Colombia. But in 1826, José Antonio Páez began to lead a movement for Venezuela to separate. Bolívar returned to Caracas and seemed to calm the situation. However, the rivalry between Bolívar and Santander, another leader, grew.

In 1828, Bolívar named himself dictator because Gran Colombia was starting to break apart. He survived an assassination attempt. In 1830, Bolívar resigned as president. Páez declared Venezuela's second independence and spoke against Bolívar. Other regions also separated. Bolívar became very sick and died in Colombia at age 47.

Venezuela from 1830 to 1908

After gaining independence from Spain, Venezuela was part of Gran Colombia. But internal problems led to Gran Colombia breaking up in 1830-1831. Venezuela declared its own independence in 1831. For the rest of the 19th century, Venezuela was often ruled by strong military leaders called caudillos. Important leaders included José Antonio Páez, Antonio Guzmán Blanco, and Cipriano Castro.

A very bloody conflict called the Federal War led to the creation of Venezuela's modern states. At the start of the 20th century, Venezuela faced international problems. These included a border dispute with Britain in 1895 and a refusal to pay foreign debts in 1902-1903.

Venezuela from 1908 to 1958

Juan Vicente Gómez (1908-1935)

In 1908, President Cipriano Castro left Venezuela for medical treatment. He left Juan Vicente Gómez in charge. Gómez then took over the government and stopped Castro from returning. This began a long period of rule by Gómez, which lasted until 1935. This time was very important because it saw the start of Venezuela's oil industry.

Gómez quickly began to pay off Venezuela's international debts. He also built a strong national army. The country developed a telegraph system, which made it harder for local leaders to start rebellions. Gómez was very strict with anyone who opposed him. He allowed people to praise him greatly, but he never built statues of himself. He often changed the constitution to suit his political goals. During his rule, Gómez appointed other presidents, but he always kept control of the army.

The Discovery of Oil

It was clear that Venezuela had a lot of oil because it would seep out of the ground. Venezuelans had tried to get oil themselves earlier. When other countries learned about Venezuela's oil, large foreign companies came to get rights to explore and drill. Gómez set up a system where he gave out large oil rights to his family and friends. These people then sold or leased their rights to foreign companies.

Gómez did not trust industrial workers or unions. He did not allow oil companies to build refineries in Venezuela. So, these refineries were built on the nearby Dutch islands of Aruba and Curaçao.

The Venezuelan oil boom started around 1918. But it really took off when a well called Barroso exploded, sending oil 200 feet into the air. It produced about 100,000 barrels of oil a day. By 1927, oil was Venezuela's most valuable export. By 1929, Venezuela exported more oil than any other country in the world.

The Venezuelan government earned a lot of money from these oil deals and taxes. This money allowed Gómez to improve Venezuela's basic services. The oil industry helped modernize the areas where it operated. However, most Venezuelan people, except those who worked for the oil companies, did not benefit much from the country's oil wealth.

When Gómez took power, Venezuela was a very poor country with many people who could not read or write. The social differences between white people and mixed-race people were still strong. When Gómez died in 1935, Venezuela was still poor and many people could not read. The population had grown from about 1.5 million to 2 million. Malaria was a major cause of death. Gómez was very strict about who could immigrate to Venezuela. He even put skin color on passports until the 1980s. Venezuela did change under Gómez. It gained radio stations and a small middle class began to form.

López Contreras and Medina Angarita (1935-1945)

After Gómez died, his war minister, Eleazar López Contreras, took over. He was a disciplined soldier. López Contreras allowed people to express their anger for a few days before taking control. He took Gómez's properties for the state, but Gómez's relatives were not usually bothered.

López Contreras allowed political parties at first, but they became too wild, so he banned them. He did not use harsh methods to stop them. One challenge he faced was a labor strike in the oil industry in 1936. He created a labor ministry, which found that the workers' complaints were fair. But he still declared the strike illegal. After this, oil companies did start to improve conditions for workers. López Contreras also started a campaign to get rid of malaria, which was completed by the next president.

López Contreras tried to create a political movement, but it did not succeed. He finished Gómez's last term and was then elected president until 1941.

In 1941, López Contreras handed power to his war minister, General Isaías Medina Angarita. Medina Angarita was different from his predecessor. He legalized all political parties, including the communists. Under Medina, there was an indirect democracy, where elections happened at the local level. Medina wanted wider national elections. He formed a pro-government party called the Venezuelan Democratic Party. But a politician named Rómulo Betancourt created a strong party for the mixed-race population, which wanted reforms but was not Marxist.

The Three Years of Democratic Action (1945-1948)

El Trienio Adeco means "The Three Years of Democratic Action." This was a three-year period from 1945 to 1948 when the popular party Democratic Action (Accion Democratica) governed Venezuela. The party came to power through a military coup against President Isaías Medina Angarita. They then held the first elections in Venezuela where everyone could vote.

In the 1947 Venezuelan general election, Democratic Action was officially elected. But they were removed from power shortly after in a military coup in 1948. This coup was peaceful and did not face much public resistance. All important members of Democratic Action were forced out. Other parties were allowed but were not allowed to speak freely.

Military Rule (1948-1958)

Venezuela was ruled by a military dictatorship for ten years, from 1948 to 1958. After the 1948 coup, three military officers controlled the government. In 1952, they held presidential elections. The results were not what the government wanted, so they changed them. One of the three leaders, Marcos Pérez Jiménez, became president.

His government ended with a military coup in 1958. This brought back democracy. A temporary government was put in place until elections were held in December 1958. Before the elections, three main political parties signed an agreement called the Punto Fijo Pact. This agreement helped ensure a peaceful transfer of power.

Venezuela from 1958 to 1999

Second Carlos Andrés Pérez Administration

Carlos Andrés Pérez served as president from 1974 to 1979. He was elected again in 1989. In his second term, he focused on cutting government spending and selling state-owned companies. He also wanted to attract foreign investment. He increased gasoline prices, which were very low in Venezuela. This led to higher public transport fares.

In February 1989, soon after he started his second term, Pérez faced widespread protests and looting. These events, known as El Caracazo, started in Guarenas and spread to Caracas. The government declared a state of emergency. Many people died, with official estimates around 277, but some say over 2000.

In 1992, military officers tried to overthrow Pérez. Hugo Chávez, a lieutenant-colonel, led one of these attempts. They almost captured Pérez, but he escaped. Chávez was arrested. In exchange for telling his co-conspirators to surrender, Chávez was allowed to speak on television. He famously said his goals had not yet been reached.

Later in 1992, other officers tried another coup, but it was easily stopped. Pérez's downfall came when he was legally asked to explain how he used a secret presidential fund. He refused. The supreme court and congress turned against him. Pérez was imprisoned. In 1993, Pérez handed the presidency to Ramón José Velásquez, a historian and politician. Velázquez oversaw the elections of 1993.

Second Rafael Caldera Administration

Rafael Caldera had run for president six times and won once before. He wanted to run again, but his party did not support him. So, Caldera started his own new political movement. He won the election, breaking the idea that only two main parties could win. Many people did not vote in this election. Caldera, who was 76, won because people knew him and hoped he could fix the country's problems.

Once in office, Caldera faced a major banking crisis in 1994. He put back controls on currency exchange. The economy suffered as oil prices fell, which reduced government income. A large steel company was privatized. The economic crisis continued.

Before the 1998 elections, the traditional political parties were very unpopular. Hugo Chávez Frías was ultimately elected president.

Venezuela from 1999 to Present

Chávez and the Bolivarian Revolution

Hugo Chávez was a former paratrooper who had led an unsuccessful coup attempt in 1992. He was elected president in December 1998. His main promise was to create a "Fifth Republic," with a new constitution and a new name for the country: "the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela." In 1999, voters approved a new constitution. In 2000, Chávez was re-elected. Many members of his party also won seats in the National Assembly. Chávez's supporters called his movement the Bolivarian Revolution.

In April 2002, Chávez was briefly removed from power in a coup attempt. But he was returned to power after two days because many people protested and most of the military supported him.

Chávez also stayed in power after a national strike that lasted over two months in late 2002 and early 2003. He won another election in December 2006. In December 2007, Chávez lost an election for the first time when voters rejected changes he proposed to the constitution. However, in February 2009, Chávez called another vote. This time, he proposed removing term limits for all elected officials. This was approved.

The 2010 parliamentary elections saw a new opposition group win almost as many votes as Chávez's party. But Chávez's party won more seats due to changes in the election rules. Chávez was re-elected in 2012 but died in early 2013. He was succeeded by Nicolás Maduro.

Nicolás Maduro's Presidency

- Further information: Crisis in Venezuela

First Term

President Nicolás Maduro officially became president on April 19, 2013. In October 2013, Maduro asked for special powers to rule by decree. He said this was to fight corruption and an "economic war." He also created a new agency to coordinate social programs. In November 2013, before local elections, Maduro ordered the military to take over appliance stores. This was seen as a way to control prices.

The government said it had seized thousands of tons of smuggled goods on the border with Colombia. These goods, like food and fuel, were meant for "smuggling" or "speculation."

Opposition Wins Elections

In the 2015 Venezuelan parliamentary election, the opposition won a majority of seats. However, in March 2017, the Supreme Court of Venezuela, which supported Maduro, announced that it would take over the duties of the parliament. This was because the court said the parliament was not following its rulings.

Venezuela's economy got much worse starting in 2014, made worse by falling oil prices. In 2016, prices rose by 800%, and the economy shrank by 18.6%. This led to more hunger. A survey found that nearly 75% of the population had lost an average of 19 pounds in 2016 due to not having enough food.

Following the 2017 Venezuelan constitutional crisis, and attempts to ban opposition leaders from politics, protests grew.

On May 1, 2017, after a month of protests, Maduro called for a Constituent Assembly to write a new constitution. He said this was needed to counter the opposition. The members of this assembly were not chosen in open elections. This move was criticized by many countries.

The Constituent Assembly elections were held on July 30, 2017. Over 40 countries and international groups did not recognize the election. They said it would make tensions worse. However, countries like Bolivia, Cuba, Russia, and Syria supported Maduro. The Constituent Assembly officially started on August 4, 2017.

On August 11, 2017, the US President said he would not rule out military action in Venezuela. Venezuela's defense minister criticized this statement, calling it "an act of madness."

Second Term and Ongoing Crisis

On May 20, 2018, President Nicolás Maduro won the presidential election. However, there were many claims of problems with the election. Many countries said Maduro's election was not fair. When his first term ended on January 10, 2019, he was sworn in again. This led to widespread criticism. The Organization of American States said Maduro was not a legitimate president and called for new elections.

On January 23, 2019, the head of the National Assembly, Juan Guaidó, declared himself interim president. Several countries, including the United States, immediately recognized Guaidó as the legitimate president. Maduro disagreed and cut off ties with some countries. On February 21, 2019, Maduro closed Venezuela's border with Brazil. Trucks carrying humanitarian aid from Colombia and Brazil tried to enter Venezuela but were stopped.

About 60 countries recognize Guaidó as the acting president. Countries like China, Cuba, and Russia support Maduro. Most Western and Latin American countries support Guaidó. However, support for Guaidó has decreased since a failed military uprising in April 2019.

After more international sanctions in 2019, the Maduro government stopped some socialist policies. For example, they removed controls on prices and currency. This helped the economy start to recover. In November 2019, Maduro said that using the US dollar was helping the country's economy. However, he also said that the Venezuelan bolívar would remain the national currency.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Venezuela para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Venezuela para niños