History of rockets facts for kids

Rockets were first used to help arrows fly further. This might have happened as early as the 900s in Song dynasty China. However, clearer proof of rockets shows up in the 1200s. This new technology likely spread across Eurasia after the Mongol invasions in the mid-1200s.

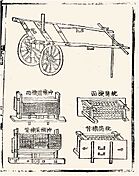

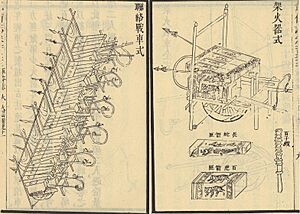

Before modern rockets, these early versions were used as weapons in China, Korea, India, and Europe. One of the first rocket launchers was the "wasp nest" fire arrow launcher, made by the Ming dynasty in China in 1380. In Europe, rockets were also used in the same year during the Battle of Chioggia. By 1451, the Joseon kingdom of Korea used a mobile multiple rocket launcher called the "Munjong Hwacha".

Later, in the mid-1700s, rockets with iron cases were used by the Kingdom of Mysore (Mysorean rockets) and the Marathas in India. The British later improved these rockets, calling them Congreve rockets. These were used in the Napoleonic Wars.

Contents

How Rockets Started

The very first idea of a device that worked like a rocket appeared around 400 BC. A Greek thinker named Archytas made a wooden bird that moved along wires using steam. This wooden pigeon was tied to a pole. When steam was let out, it pushed the pigeon in circles around the pole.

About 300 years later, Hero of Alexandria created a similar device called an aeolipile. It was a sphere on top of a water basin. Fire heated the water, turning it into steam that went into the sphere. The steam escaped through two L-shaped tubes, making the sphere spin. These early devices showed the basic idea of how rockets work: the "action-reaction principle."

Early Rocket Inventions

The exact date when the first gunpowder rocket was invented is debated. Some old Chinese records say it was invented by Feng Zhisheng in 969 or Tang Fu in 1000. However, some historians believe rockets couldn't have existed before the 1100s because the gunpowder recipes from that time weren't strong enough for rockets.

Rockets might have been used in 1232. Reports describe "fire arrows" and "iron pots" that exploded loudly, causing damage over a wide area. The Song navy also used rockets in a military practice in 1245. In 1264, a "ground-rat" firework, which was a type of rocket, scared an Empress at a party.

Rocket Improvements Over Time

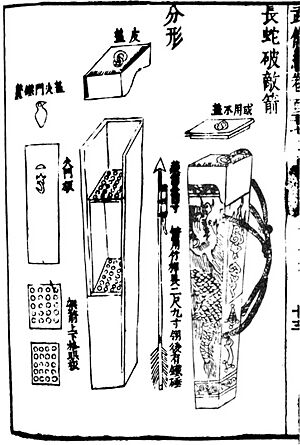

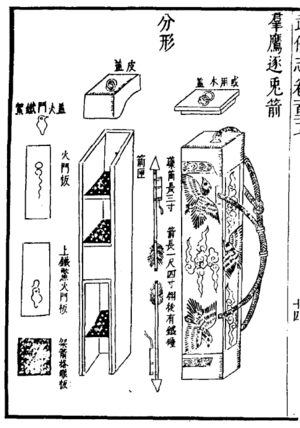

Later, rockets were described in a Chinese military book called Huolongjing (Fire Drake Manual), written by Jiao Yu in the mid-1300s. This book mentions the first known multistage rocket, called the "fire-dragon issuing from the water." It was likely used by the Chinese navy.

The Ming army ordered "wasp nests" rocket launchers in 1380. In 1400, a Ming loyalist named Li Jinglong used rocket launchers against the army of Zhu Di.

How Rocket Technology Spread

Historians believe that rocket festivals in southern China and Laos might have helped spread rocket technology across Asia.

Mongol Empire's Role

The Mongols adopted the Chinese fire arrows. They even hired Chinese rocket experts to work in their army. Rockets are thought to have spread to other parts of Eurasia through the Mongol invasions in the mid-1200s. Rocket-like weapons were reportedly used in the Battle of Mohi in 1241.

Rockets in the Middle East

Between 1270 and 1280, a person named Hasan al-Rammah wrote a book about military horsemanship and war devices. It included 107 gunpowder recipes, with 22 of them for rockets. The words al-Rammah used suggest that these gunpowder weapons, like rockets, came from China. For example, Arabs called saltpeter (a key ingredient in gunpowder) "snow of China" or "Chinese snow." They also called rockets "Chinese arrows" and fireworks "Chinese flowers."

Rockets in India

Mercenaries (soldiers for hire) are recorded using handheld rockets in India in 1300. By the mid-1300s, Indians were also using rockets in battles.

Mysorean Rockets in India

-

A painting showing the Mysorean army fighting the British with Mysorean rockets.

-

A Mysorean soldier using his Mysorean rocket as a flag.

The Kingdom of Mysore used Mysorean rockets in the 1700s during the Anglo-Mysore Wars. In 1792, Tipu Sultan, the ruler of Mysore, successfully used iron-cased rockets against the larger British East India Company forces. The British became very interested in this technology and improved it in the 1800s. Using iron tubes for the rocket fuel made them more powerful and able to fly further, up to 2 kilometers.

After Tipu's defeat, the British captured the Mysore iron rockets. These rockets inspired the Congreve rocket, which was then used in the Napoleonic Wars.

Later Rocket Use in India

According to James Forbes, the Marathas also used iron-cased rockets in their battles.

Rockets in Korea

The Korean kingdom of Joseon started making gunpowder in 1374. By 1377, they were producing cannons and rockets. However, the famous "Munjong hwacha" multiple rocket launching carts didn't appear until 1451.

Rockets in Europe

In Europe, Roger Bacon mentioned gunpowder in his book in 1267. However, rockets didn't appear in European warfare until the 1380 Battle of Chioggia.

Some historians say rockets were used in the war between Genoa and Venice at Chioggia in 1380. This is the earliest recorded use of rocket artillery in Europe.

Jean Froissart (who lived from about 1337 to 1405) had the idea of launching rockets through tubes to make them fly more accurately. This idea was a very early version of the modern Rocket-propelled grenade.

Konrad Kyeser described rockets in his military book Bellifortis around 1405. He talked about three types: swimming rockets, free-flying rockets, and rockets that were tied down.

Joanes de Fontana described rockets that looked like flying doves, running hares, and even a large car powered by three rockets. He also imagined a big rocket torpedo shaped like a sea monster.

Later European Rocket Developments

In the mid-1500s, Conrad Haas wrote a book about rocket technology, combining fireworks and weapons. His work described how multi-stage rockets could work, different fuel mixtures, and even new shapes for fins and nozzles.

The word "rocket" comes from the Italian word rocchetta, meaning "little spindle," because early rockets looked like the spools used for thread. This Italian word was adopted into German in the mid-1500s and into English around 1610. Johann Schmidlap, a German fireworks maker, is thought to have experimented with multi-stage rockets in 1590.

A legendary Ottoman aviator named Lagari Hasan Çelebi supposedly made a successful manned rocket flight in 1633. He is said to have launched in a 7-winged rocket using a lot of gunpowder from Istanbul.

A Polish nobleman named Kazimierz Siemienowicz wrote a book called "Great Art of Artillery" in 1650. This book was used as a basic artillery manual in Europe for over 200 years. It gave designs for rockets, including multi-stage rockets and rockets with delta wing stabilizers.

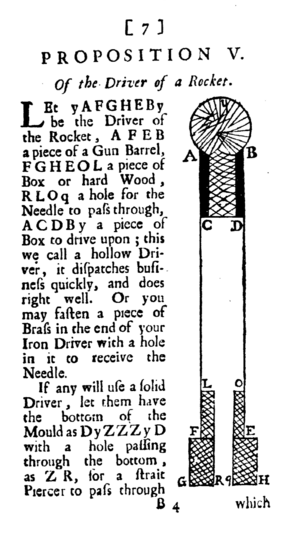

In 1696, Robert Anderson suggested making rockets out of metal gun barrels. He thought metal would be much stronger than wood or cardboard for the rocket casing.

Rockets in the 1800s

William Congreve (1772–1828) was a very important person in rocket development. Starting in 1801, he studied the Indian Mysorean Rockets and began a strong development program. Congreve created a new fuel mixture and a rocket motor with a strong iron tube and a pointed nose. This early Congreve rocket weighed about 14.5 kilograms. The first public demonstration of these rockets was in 1805. They were used effectively during the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812.

After this, military rockets spread across the Western world. During the Battle of Baltimore in 1814, rockets fired at Fort McHenry were the source of the "rockets' red glare" in the American national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner". Rockets were also used in the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Early rockets were not very accurate. They often flew off course. The early Mysorean and British Congreve rockets tried to fix this by adding a long stick to the end of the rocket, like modern bottle rockets. This made it harder for the rocket to change direction. The largest Congreve rocket, the Carcass, had a 4.6-meter stick.

In 1815, Alexander Dmitrievich Zasyadko (1779–1837) began working on military gunpowder rockets in Russia. He built platforms that could fire many rockets at once (6 rockets at a time). He also developed ways to use rockets in battle. In 1820, he became head of several important military facilities and formed the first rocket unit in the Imperial Russian Army.

In Poland, artillery captain Józef Bem (1794–1850) experimented with rockets, publishing a report in 1819. The 1st Rocketeer Corps was formed in 1822 and first saw combat in 1830.

Accuracy greatly improved in 1844 when William Hale changed the rocket design. He made the rocket spin as it flew, like a bullet. This "Hale rocket" didn't need a stick, flew further, and was much more accurate.

In 1865, British Colonel Edward Mounier Boxer improved the Congreve rocket by putting two rockets in one tube, one behind the other.

Rocket Pioneers of the Early 1900s

At the start of the 1900s, people became very interested in space travel. Writers like Jules Verne and H. G. Wells wrote exciting stories about it. Scientists then realized that rockets could actually make space travel possible.

In 1903, a math teacher named Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857–1935) published the first serious scientific work on space travel. He developed the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, which explains how rockets move. He also suggested using liquid hydrogen and oxygen as rocket fuel. His work was not well known outside the Soviet Union, but it inspired more research there.

In 1912, Robert Esnault-Pelterie published his own ideas on rocket theory and space travel. He also figured out the rocket equation and calculated the energy needed to travel to the Moon and planets. He even suggested using atomic power for a jet drive.

Also in 1912, Robert Goddard began to seriously study rockets. He realized that regular solid-fuel rockets needed three improvements. First, fuel should burn in a small chamber. Second, rockets could be built in stages. Third, the speed of the exhaust gases could be greatly increased using a special nozzle. He patented these ideas in 1914 and also developed the math for rocket flight.

Goddard worked on solid-propellant rockets from 1914. He showed a small battlefield rocket to the US Army just before World War I ended. He also started developing liquid-propellant rockets in 1921. Even though he wasn't always taken seriously, Goddard secretly developed and flew a small liquid-fueled rocket. He created technology for 214 patents, which his wife published after his death.

During World War I, Yves Le Prieur, a French naval officer, developed air-to-air solid-fuel rockets. These Le Prieur rockets were used to destroy enemy observation balloons. They were first tested in 1916 and proved very effective when fired from a short distance.

In 1920, Goddard published his ideas and experiment results in a paper. He mentioned sending a solid-fuel rocket to the Moon, which got a lot of attention. Some people praised him, while others made fun of him. The New York Times even wrote an editorial suggesting he didn't understand basic physics.

That Professor Goddard, with his 'chair' in Clark College and the countenancing of the Smithsonian Institution, does not know the relation of action to reaction, and of the need to have something better than a vacuum against which to react – to say that would be absurd. Of course he only seems to lack the knowledge ladled out daily in high schools."

However, rockets actually push against their own exhaust gases, so they work perfectly fine in a vacuum.

In 1923, German scientist Hermann Oberth (1894–1989) published his book "The Rocket into Planetary Space." In 1929, he published another book, "Ways to Spaceflight," and tested a liquid-fueled rocket engine.

In 1924, Tsiolkovsky also wrote about multi-stage rockets, calling them 'Cosmic Rocket Trains'.

Modern Rocketry Begins

Before World War II

Modern rockets began in the US when Robert Goddard added a special nozzle to a liquid-fueled rocket engine. This nozzle turned the hot gas into a fast, directed jet, more than doubling the rocket's power. On March 16, 1926, Goddard launched the world's first liquid-fueled rocket in Auburn, Massachusetts.

In the 1920s, many rocket research groups appeared worldwide. In the Soviet Union, rocket research began in 1921. They tested a solid-fuel rocket in 1928 that flew 1,300 meters. In 1931, they successfully used rockets to help aircraft take off. They also tested firing rockets from aircraft and the ground. In 1933, two groups merged to form the Reactive Scientific Research Institute (RNII), continuing rocket development. They designed rockets for air-to-air, ground-to-ground, and other combat uses. The RS-82 rockets were carried by fighter planes, and heavier RS-132 rockets by bombers. Many Soviet Navy ships also used RS-82 rockets. In August 1939, Soviet planes used rockets in combat against Japanese aircraft, shooting down many planes.

In 1927, the German car company Opel started showing off rocket vehicles with Max Valier and Friedrich Wilhelm Sander. In 1928, Fritz von Opel drove a rocket car on a race track. They also put rocket power on a glider, which was destroyed on its second flight. Later, Julius Hatry built a special glider for von Opel's rocket program. On September 30, 1929, von Opel himself flew the world's first public manned rocket-powered flight. These public demonstrations created a lot of excitement in Germany.

An amateur rocket group in Germany, the VfR, included Wernher von Braun. He later became the head of the army research station that designed the V-2 rocket for the Nazis. When private rocket engineering was banned in Germany, Sander was arrested and forced to sell his company.

In 1932, Wernher von Braun, a young engineering genius, joined the German Army's secret rocket program. He dreamed of space travel and didn't initially see the military use for rockets.

In 1927, a team of German rocket engineers formed the "Society for Space Travel" (VfR). In 1931, they launched a liquid-propellant rocket.

Similar work was done by Austrian professor Eugen Sänger from 1932. He later moved to Germany and worked on rocket-powered spaceplanes.

In 1936, a British research program began working on unguided solid-fuel rockets for anti-aircraft defense. Tests were carried out in Jamaica in 1939.

In the 1930s, the German military became interested in rockets because the Treaty of Versailles limited their long-range weapons. They saw rockets as a way around this. The military funded the VfR team at first, but then created its own research team. Von Braun joined this military team and developed long-range weapons for Nazi Germany in World War II.

In June 1938, the Soviet Reactive Scientific Research Institute (RNII) began developing a multiple rocket launcher based on the RS-132 rocket. In August 1939, the finished rocket launcher, called the BM-13 / Katyusha, was ready. It could fire many rockets at once over a range of 5,500 meters. By June 1941, 40 launchers were built before Germany invaded the Soviet Union.

World War II Rockets

At the start of World War II, the British used unguided anti-aircraft rockets on their warships. By 1940, the Germans developed a surface-to-surface multiple rocket launcher called the Nebelwerfer.

The Soviet Katyusha rocket launchers were top secret. On July 14, 1941, seven launchers were first used in battle in Russia. They destroyed a large group of German troops, tanks, and trucks, causing panic. After this success, mass production was ordered. The Katyusha was cheap to make and didn't need heavy factory equipment. By the end of 1942, over 3,200 Katyusha launchers were built, and by the end of the war, about 10,000 were made, along with 12 million rockets.

During World War II, Major-General Dornberger led the German army's rocket program, and von Braun was the technical director. They led the team that built the Aggregat-4 (A-4) rocket. This rocket became the first vehicle to reach outer space during its test flights in 1942 and 1943. By 1943, Germany started mass-producing the A-4 as the V-2 ("Vengeance Weapon" 2). This was a ballistic missile with a 320 km range, carrying a 1,130 kg warhead at 4,000 km/h. Its super-fast speed meant there was no defense against it. Germany used the V-2 to bomb southern England and parts of Allied-controlled western Europe from 1944 to 1945. After the war, the V-2 became the basis for early American and Soviet rocket designs.

Thousands of V-2s were fired at Allied nations, mainly Belgium, England, and France. While they couldn't be stopped, their guidance system wasn't accurate enough for military targets. Still, 2,754 people in England were killed by V-2s. Sadly, 20,000 slave laborers died during the construction of V-2s. Although the V-2 didn't change the war's outcome, it showed how powerful guided rockets could be as weapons.

Germany also developed several guided and unguided air-to-air, ground-to-air, and ground-to-ground missiles during the war.

After World War II

-

Dornberger and Von Braun after being captured by the Allies.

-

The R-7 "Vostok" rocket on display in Moscow.

-

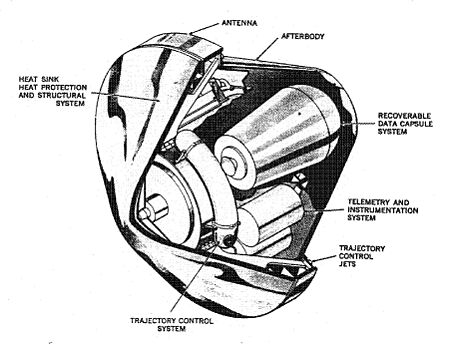

A prototype of the General Electric (USA) Mk-2 Reentry Vehicle.

At the end of World War II, American, British, and Russian teams raced to capture German rocket technology and scientists from Peenemünde. The US gained the most, bringing many German rocket scientists, including von Braun, to America in Operation Paperclip. In the US, the same rockets designed to attack Britain were used for research to develop new technology. The V-2 evolved into the American Redstone rocket, used in the early space program.

After the war, rockets were used to study high-altitude conditions, like temperature and pressure. This research continued in the US under von Braun.

In the Soviet Union, research continued under Sergei Korolev. With help from German technicians, the V-2 was launched and copied as the R-1 missile. German designs were later dropped, and new engines formed the basis of the first intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), the R-7. The R-7 launched the first satellite, Sputnik 1, and later Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space. This rocket is still used today. These achievements brought more money for rocket research.

One big problem was atmospheric reentry – how to get a spacecraft back through Earth's atmosphere without burning up. Scientists knew that a spacecraft had enough energy to vaporize itself. The mystery was solved in the US in 1951. Scientists found that a blunt (rounded) shape worked best as a heat shield. With this shape, about 99% of the heat goes into the air, not the vehicle. This allowed safe return of spacecraft.

This discovery, first kept secret, was published in 1958. Blunt body theory made possible the heat shield designs for the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, and Soyuz space capsules. This allowed astronauts and cosmonauts to survive re-entry. Some spaceplanes like the Space Shuttle also used this idea. The Space Shuttle entered the atmosphere at a very high angle of attack, creating a large shock wave that pushed most of the heat away from the vehicle.

Cold War Rocketry

Rockets became very important militarily as modern intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). It was realized that nuclear weapons carried on a rocket could not be stopped once launched. Rockets like the R-7, Atlas, and Titan became ways to deliver these weapons.

Partly because of the Cold War, the 1960s saw fast development of rocket technology. This was especially true in the Soviet Union (Vostok, Soyuz, Proton) and the United States (like the X-15 and X-20 Dyna-Soar aircraft). Other countries like France, Britain, and Japan also did important research. Rockets were increasingly used for Space exploration, sending back pictures from the Moon and uncrewed flights to Mars.

In America, the crewed spaceflight programs, Project Mercury, Project Gemini, and later the Apollo program, led to the first crewed Moon landing in 1969 using the Saturn V rocket. This even made the New York Times take back its earlier 1920 editorial that said spaceflight couldn't work:

Further investigation and experimentation have confirmed the findings of Isaac Newton in the 17th century and it is now definitely established that a rocket can function in a vacuum as well as in an atmosphere. The Times regrets the error.

In the 1970s, the United States made five more Moon landings before ending the Apollo program in 1975. The replacement, the partially reusable Space Shuttle, was meant to be cheaper, but it didn't greatly reduce costs. Meanwhile, in 1973, the Ariane program began in Europe. By 2000, Ariane rockets launched many communication satellites.

Rocket Market Competition Today

Since the early 2010s, new private companies have started offering spaceflight services. This has brought a lot of competition to the rocket launch business.

Before, only national space programs launched rockets. Later, commercial companies became customers, but the rockets were still built by governments. In the early 2010s, privately developed rockets and launch services appeared. Companies now face economic reasons to be efficient, not just political ones. This has led to much lower prices for rocket launches and new abilities, creating a new phase of competition in the space launch market.

See also