History of the Central African Republic facts for kids

The history of the Central African Republic (often called CAR) is divided into different time periods. The first people started settling in this area about 10,000 years ago. They were nomads who began to farm and fish.

Contents

Early History of the Central African Republic

About 10,000 years ago, the land became drier, forcing hunter-gatherers to move south. Some groups settled and started farming, which was part of the Neolithic Revolution. They first grew white yams, then millet and sorghum. Later, they grew African oil palm, which helped them get better food and allowed their groups to grow. Bananas also arrived, adding important carbohydrates to their diet and were used to make drinks.

This farming revolution, along with a "Fish-stew Revolution" where people started fishing and using boats, helped move goods around. Products were often carried in ceramic pots, which are the first known examples of art from the people in this region.

The Bouar Megaliths in western CAR show that people lived there with advanced skills around 3500-2700 BC. Ironworking came to the region by 1000 BC, likely from early Bantu cultures in what is now Nigeria or Cameroon. Evidence of ironworking has been found at the Gbabiri site in CAR, dating back to 896-773 BC. Some experts believe ironworking might have started even earlier, around 2000 BC, at the Oboui site, but this is debated.

During the Bantu Migrations (about 1000 BC to AD 1000), different groups moved into the area. Ubangian-speaking people spread east from Cameroon to Sudan. Bantu-speaking people settled in the southwest of CAR. Central Sudanic-speaking people settled along the Ubangi River in central and eastern CAR.

The economy in this region was mainly based on trading copper, salt, dried fish, and textiles.

The area of modern CAR was settled from at least the 7th century by large empires. These included the Kanem-Bornu, Ouaddai, Baguirmi, and Dafour groups. They were based around Lake Chad and the Upper Nile.

Early Modern History and Trade

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Muslim slave traders started raiding the region. People captured were sent to the Mediterranean, Europe, Arabia, the Americas, or to slave ports in West Africa. The Bobangi people became important slave traders. They sold captives to the Americas, using the Ubangi River to reach the coast. In the 18th century, the Bandia-Nzakara people created the Bangassou Kingdom along the Ubangi River.

More people moved into the area in the 18th and 19th centuries. These new groups included the Zande, Banda, and Baya-Mandjia.

Colonial Period and European Influence

European countries began to take over Central African land in the late 19th century. This was part of the "Scramble for Africa". Count Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza created the French Congo. He sent teams up the Ubangi River from Brazzaville to expand France's claims in Central Africa. Belgium, Germany, and the United Kingdom also wanted to claim land in the region. In 1875, the Sudanese sultan Rabih az-Zubayr ruled Upper-Oubangui, which included today's Central African Republic. Europeans, mainly French, German, and Belgians, arrived in the area in 1885.

France officially claimed the area through an agreement in 1887 with the Congo Free State (owned by Leopold II of Belgium). This agreement gave France control of the right bank of the Oubangui River. In 1889, the French set up a post on the Ubangi River at Bangui. From 1890 to 1891, de Brazza sent teams up the Sangha River and eastward along the Ubangi River. Their goal was to connect French territories in Africa. In 1894, France's borders with Leopold II's Congo Free State and German Cameroon were set. France then declared Ubangi-Shari a French territory.

French Control and Administration

In 1899, the border between the French Congo and Sudan was set. This meant France did not get the access to the Nile River it wanted.

In 1900, the French defeated Rabih's forces in the Battle of Kousséri. But they did not fully control Ubangi-Shari until 1903. That's when they set up their colonial government across the territory.

Once the borders were agreed upon, France had to figure out how to pay for ruling and developing the land. The success of Leopold II's companies in the Congo Free State made France grant 17 private companies large areas in Ubangi-Shari in 1899. These companies could use the land to buy local products and sell European goods. In return, they promised to pay rent to France and help develop their areas. These companies often used harsh methods to force local people to work.

At the same time, the French colonial government made local people pay taxes and work for free. Companies and the French government sometimes worked together to force Central Africans to labor. Some French officials reported abuses by private company guards and their own troops. But efforts to hold these people responsible often failed. When news of these terrible acts reached France, there was public outcry. Investigations were done, and some small changes were made. However, the situation in Ubangi-Shari stayed mostly the same.

In 1906, Ubangi-Shari was joined with the Chad colony. In 1910, it became one of the four territories of the Federation of French Equatorial Africa (AEF). The others were Chad, Middle Congo, and Gabon.

During the first ten years of French rule (1900-1910), local rulers increased slave-raiding and selling local goods to Europe. They used their agreements with the French to get more weapons. These weapons were used to capture more slaves. Much of eastern Ubangi-Shari lost many people because of this slave trade. After the French broke the power of local African rulers, slave raiding greatly decreased.

In 1911, some areas were given to Germany as part of a deal. This deal gave France more freedom in Morocco. Western Ubangi-Shari stayed under German rule until World War I. After the war, France took back the territory using Central African troops.

The next thirty years saw small revolts against French rule. A new economy based on plantations grew. From 1920 to 1930, roads were built, and cash crops like cotton were encouraged. Health services were set up to fight sleeping sickness. Protestant missions were also started. However, new forms of forced labor were also introduced. Many Ubangians were forced to work on the Congo-Ocean Railway. Many died from exhaustion and illness due to the bad conditions.

In 1925, French writer André Gide wrote about the terrible effects of forced labor for the Congo-Ocean railroad. He showed the ongoing cruelties against Central Africans by companies like the Forestry Company of Sangha-Ubangi. In 1928, a big uprising called the Kongo-Wara rebellion started in Western Ubangi-Shari. It lasted for several years. The size of this rebellion, which was perhaps the largest anti-colonial uprising in Africa during those years, was kept secret from the French public. It showed strong opposition to French rule and forced labor.

Resistance to Colonial Rule

While there were many small revolts, the Kongo-Wara rebellion was the largest. Peaceful protests against forced work for the railway and rubber tapping began in the mid-1920s. These protests turned violent in 1928, when over 350,000 local people rebelled. The main leader, Karnou, was killed in December 1928, but the rebellion was not fully stopped until 1931.

Economic Growth and World War II

In the 1930s, cotton, tea, and coffee became important crops in Ubangi-Shari. The mining of diamonds and gold also began. Several cotton companies were given the only right to buy cotton in large areas. This allowed them to set low prices for farmers, ensuring big profits for their owners.

In September 1940, during Second World War, French officers who supported Charles de Gaulle took control of Ubangi-Shari. In August 1940, the territory, along with the rest of the AEF, joined General Charles de Gaulle's call to fight for Free France.

Path to Independence

After World War II, the French government began reforms that eventually led to full independence for all French territories in Africa. In 1946, all AEF residents became French citizens and could create local assemblies. The assembly in CAR was led by Barthélemy Boganda, a Catholic priest. He was known for speaking strongly in the French Assembly about the need for African freedom. In 1956, new French laws removed some voting inequalities and allowed for self-government in each territory.

In September 1958, a French vote dissolved the AEF. On December 1 of the same year, the Assembly declared the birth of the independent Central African Republic. Boganda became its head of government. Boganda ruled until he died in a plane crash on March 29, 1959. His cousin, David Dacko, took his place. On July 12, 1960, France agreed to the Central African Republic becoming fully independent. On August 13, 1960, the Central African Republic became an independent country, and David Dacko became its first President.

Independence and New Leaders

David Dacko began to strengthen his power soon after becoming president in 1960. He changed the Constitution to make his government a one-party state. The president would have strong powers and be elected for seven years. On January 5, 1964, Dacko was elected in an election where he was the only candidate.

During his first term, Dacko greatly increased diamond production. He ended the special right that only certain companies had to mine diamonds. He allowed any Central African to dig for diamonds. He also had a diamond-cutting factory built in Bangui. Dacko encouraged quickly replacing foreign administrators with Central Africans. This led to more corruption and less efficiency. He also hired many more civil servants, which greatly increased the part of the national budget needed for salaries.

Dacko struggled to keep France's support while also showing he was independent. To find other sources of support and show his independence in foreign policy, he built closer ties with the People's Republic of China. By 1965, Dacko had lost the support of most Central Africans. He may have been planning to resign when he was overthrown.

Bokassa and the Central African Empire

On January 1, 1966, Colonel Jean-Bédel Bokassa took power in a quick and almost bloodless coup. Bokassa got rid of the 1959 constitution and the National Assembly. He then made a rule that gave all law-making and executive powers to the president. On March 4, 1972, Bokassa became president for life. On December 4, 1976, the republic became a monarchy called the Central African Empire. Bokassa was crowned as Emperor Bokassa I. His rule was known for many human rights violations.

On September 20, 1979, Dacko overthrew Bokassa in a bloodless coup.

Kolingba's Rule

Dacko's efforts to improve the economy and politics did not work well. So, on September 20, 1981, General André Kolingba overthrew him in a bloodless coup. Kolingba suspended the constitution and ruled with a military group called the Military Committee for National Recovery (CMRN) for four years.

In 1985, the CMRN was dissolved. Kolingba named a new government with more civilian members, signaling a return to civilian rule. The move towards democracy sped up in 1986 with a new political party, the Rassemblement Démocratique Centrafricain (RDC). A new constitution was also written and approved by a national vote. General Kolingba became the constitutional President on November 29, 1986. The constitution created a National Assembly with 52 elected members, chosen in July 1987. Local elections were held in 1988. Kolingba's two main political opponents, Abel Goumba and Ange-Félix Patassé, did not take part in these elections because their parties were not allowed.

By 1990, a movement for democracy became very active, inspired by the fall of the Berlin Wall. In May 1990, 253 important citizens asked for a National Conference. Kolingba refused and arrested several opponents. Pressure from a group of countries and agencies (GIBAFOR) finally made Kolingba agree to hold free elections in October 1992.

Kolingba claimed there were problems with the elections and stopped the results. He held onto power. GIBAFOR put strong pressure on him to create a Provisional National Political Council (CNPPR) and an "Mixed Electoral Commission" with members from all political parties.

Patassé's Presidency

When elections were finally held in 1993, with international help, Ange-Félix Patassé led in the first round. Kolingba came in fourth. In the second round, Patassé won 53% of the vote. Most of Patassé's support came from the Gbaya, Kare, and Kaba voters in the northwest. Patassé's party, the Movement for the Liberation of the Central African People (MLPC), won the most seats in parliament but not a full majority. This meant they needed other parties to rule effectively.

Patassé removed former President Kolingba from his military rank in March 1994. He then accused several former ministers of crimes. Patassé also removed many Yakoma people from important government jobs. Two hundred mostly Yakoma members of the presidential guard were also fired or moved to the army. Kolingba's RDC party said that Patassé's government was unfairly targeting the Yakoma.

A new constitution was approved on December 28, 1994, but it did not have much effect on the country's politics. In 1996–1997, public trust in the government decreased. Three military uprisings against Patassé's rule happened, causing much damage and increasing ethnic tension.

On January 25, 1997, the Bangui Agreements were signed. These agreements allowed an inter-African military mission (MISAB) to be sent to CAR. Mali's former president, Amadou Toumani Touré, helped mediate. Former rebels joined the government on April 7, 1997. The MISAB mission was later replaced by a U.N. peacekeeping force, MINURCA.

In 1998, parliamentary elections showed Kolingba's RDC winning 20 out of 109 seats, a big political comeback. However, in 1999, Patassé won free elections to become president for a second term, despite public anger in cities about his rule.

Bozizé Takes Power

On May 28, 2001, rebels attacked important buildings in Bangui in an unsuccessful coup attempt. The army chief of staff and General François N'Djadder Bedaya were killed. But Patassé kept power with help from troops from Libya and rebel soldiers from the DRC.

After the failed coup, groups loyal to Patassé sought revenge against rebels in many parts of Bangui. This caused unrest, leading to homes being destroyed and opponents being tortured and killed.

Patassé suspected that General François Bozizé was involved in another coup attempt. This led Bozizé to flee with loyal troops to Chad. In March 2003, Bozizé launched a surprise attack against Patassé, who was out of the country. This time, Libyan troops and Congolese rebel soldiers could not stop the rebels. Bozizé's forces took control of the country, overthrowing Patassé. On March 15, 2003, rebels entered Bangui and made Bozizé president.

Patassé was found guilty of major crimes in Bangui. CAR brought a case against him and Jean-Pierre Bemba to the International Criminal Court. They were accused of many crimes in stopping one of the uprisings against Patassé.

Bozizé won the 2005 presidential election. His group also led in the 2005 legislative election.

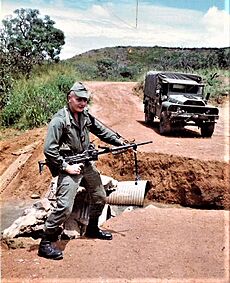

The Bush War (2003–2007)

After Bozizé took power in 2003, the Central African Republic Bush War began. It started with a rebellion by the Union of Democratic Forces for Unity (UFDR), led by Michel Djotodia. This quickly grew into major fighting in 2004. The UFDR rebel forces included several allied groups.

In early 2006, Bozizé's government seemed stable.

On April 13, 2007, a peace agreement was signed in Birao between the government and the UFDR. The agreement offered forgiveness for the UFDR, recognized it as a political party, and allowed its fighters to join the army. Further talks led to an agreement in 2008 for peace, a unity government, and elections in 2009 and 2010. The new unity government was formed in January 2009.

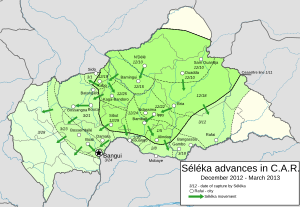

Civil War (2012–2014)

In late 2012, a group of old rebel groups, now called Séléka, started fighting again. Two new groups also joined them, along with a Chadian group.

On December 27, 2012, CAR President Francois Bozizé asked for international help, especially from France and the United States. French President François Hollande said no. He stated that the 250 French troops at Bangui M'Poko International Airport were "in no way to intervene in the internal affairs."

On January 11, 2013, a ceasefire agreement was signed in Libreville, Gabon. The rebels dropped their demand for President François Bozizé to resign. But he had to appoint a new prime minister from the opposition party by January 18, 2013. On January 13, Bozizé signed a rule that removed Prime Minister Faustin-Archange Touadéra from power, as part of the agreement. On January 17, Nicolas Tiangaye was appointed Prime Minister.

On March 24, 2013, rebel forces heavily attacked the capital Bangui. They took control of major buildings, including the presidential palace. Bozizé's family fled across the river to the Democratic Republic of the Congo and then to Yaounde, the capital of Cameroon, where he found temporary safety.

Djotodia's Administration

Séléka leader Michel Djotodia declared himself President. Djotodia said there would be a three-year transition period and that Tiangaye would continue as Prime Minister. Djotodia quickly suspended the constitution and dissolved the government and the National Assembly. He then reappointed Tiangaye as Prime Minister on March 27, 2013. Top military and police officers met with Djotodia and recognized him as president on March 28, 2013. Catherine Samba-Panza became the interim president on January 23, 2014.

Peacekeeping efforts largely moved from the ECCAS-led MICOPAX to the African Union-led MISCA, which started in December 2013. In September 2014, MISCA handed over its authority to the UN-led MINUSCA. The French peacekeeping mission was known as Operation Sangaris.

Civil War (2015–Present)

By 2015, the government had little control outside of the capital, Bangui. When Séléka broke up, its former fighters formed new groups that often fought each other.

Armed groups created their own areas where they set up checkpoints and collected illegal taxes. They made millions of dollars from illegal coffee, mineral, and timber trades. Noureddine Adam, the leader of the rebel group Popular Front for the Rebirth of Central African Republic (FRPC), declared the independent Republic of Logone on December 14, 2015. By 2017, more than 14 armed groups were fighting for land. About 60% of the country was controlled by four main groups led by former Séléka leaders. These included the FRP led by Adam, the Union Pour la Paix en Centrafrique (UPC) led by Ali Darassa, and the Mouvement patriotique pour la Centrafrique (MPC) led by Mahamat Al-Khatim. These groups were often linked to specific ethnic groups. Fighting between ex-Séléka groups in the north and east, and Anti-balaka groups in the south and west, decreased but small fights continued.

In February 2016, after a peaceful election, former Prime Minister Faustin-Archange Touadéra was elected president. In October 2016, France announced that Operation Sangaris, its peacekeeping mission, was a success and largely pulled out its troops.

Tensions grew in November 2016 as ex-Séléka groups fought over control of a goldmine. A group formed by the MPC and the FPRC attacked the UPC.

Conflict in Ouaka

Most of the fighting was in the Ouaka region, which has the country's second largest city, Bambari. This area is important because it is between Muslim and Christian regions and has resources. The fight for Bambari in early 2017 forced 20,000 people to leave their homes. MINUSCA sent many troops to stop the FPRC from taking the city. In February 2017, Joseph Zoundeiko, the chief of staff of FPRC, was killed by MINUSCA after crossing a forbidden line. At the same time, MINUSCA helped remove Darassa from the city. This made the UPC look for new territory, spreading the fighting from cities to rural areas that were previously safe.

MINUSCA, which was spread thin, relied on Ugandan and American special forces to keep peace in the southeast. These forces were part of a mission to stop the Lord's Resistance Army, but that mission ended in April 2017. By late 2017, fighting mostly moved to the Southeast. The UPC reorganized and was chased by the FPRC and Anti-balaka. The level of violence was as high as in the early stages of the war. About 15,000 people fled their homes in an attack in May, and six U.N. peacekeepers were killed. This was the deadliest month for the mission so far.

In June 2017, another ceasefire was signed in Rome by the government and 14 armed groups, including FPRC. But the next day, fighting between an FPRC group and Anti-balaka militias killed over 100 people. In October 2017, another ceasefire was signed between the UPC, the FPRC, and Anti-balaka groups. The FPRC announced Ali Darassa as a coalition vice-president, but fighting continued afterward. By July 2018, the FPRC, now led by Abdoulaye Hissène and based in the northeastern town of Ndélé, had troops threatening to move towards Bangui. More clashes between the UPC and MINUSCA/government forces happened in early 2019.

Conflicts in Western and Northwestern CAR

In Western CAR, a new rebel group called Return, Reclamation, Rehabilitation (3R) formed in 2015. It had no known links to Séléka or Anti-balaka. Its leader, General Sidiki Abass, claimed 3R would protect Muslim Fulani people from an Antibalaka militia. 3R is accused of forcing 17,000 people from their homes in November 2016 and at least 30,000 people in the Ouham-Pendé region in December 2016.

For some time, Northwestern CAR, around Paoua, was divided between Revolution and Justice (RJ) and Movement for the Liberation of the Central African Republic (MNLC). But fighting broke out after the killing of RJ leader, Clément Bélanga, in November 2017. This conflict forced 60,000 people from their homes since December 2017. The MNLC, founded in October 2017, was led by Ahamat Bahar. It is said to be supported by Fulani fighters from Chad. The Christian group RJ was formed in 2013, mostly by members of former President Ange Felix Patassé's presidential guard. They were mainly from the Sara-Kaba ethnic group.

2020s and Recent Events

In December 2020, President Faustin Archange Touadéra was reelected in the first round of the presidential election. The opposition did not accept the result, claiming there were problems and fraud. Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group have supported President Faustin-Archange Touadéra in the fight against rebels. Russia's Wagner group has been accused of bothering and scaring civilians.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la República Centroafricana para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la República Centroafricana para niños

- Brazzaville Conference

- French Equatorial Africa

- History of Central Africa

- Ubangi-Shari

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |