History of the English fiscal system facts for kids

The history of England's money system shows how a country's way of collecting and spending money can grow and change over a very long time. From the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066 all the way to the early 1900s, there were many big changes. But even with these changes, like the English Civil War in the 1600s and the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the basic ideas of how England managed its money stayed connected.

In early England, before the Normans, the king's money was mostly about his own household. He collected payments from his lands and special fees when needed. There wasn't much of a national money system like we have today. But when the Normans came, they brought new ideas about keeping records and having a central treasury.

After the Glorious Revolution, Parliament (the group of elected representatives) started to have much more control over the country's money. Also, land rents became less important as a way to make money for the government. This led to new kinds of taxes.

Contents

Setting Up the Money System

When William the Conqueror united England and Normandy, he brought in new ways to manage things, especially money. The Norman and Plantagenet kings created a very important office called the Exchequer. This was like a big money office with different parts for checking accounts and managing royal income.

Even before the Exchequer, the Domesday Book was created. This was a huge survey of England's lands and wealth, mainly to figure out who owed taxes. It showed that King William I wanted to keep a close eye on all the ways the government could make money. The Exchequer system, which became very strong in the 1100s, helped the king collect his income and keep track of spending.

The book Dialogue of the Exchequer (written around 1176) describes a full system for collecting the king's money and checking accounts. This clever system helped the king get more money, and many important church leaders and lawyers were involved in making it work.

King's Special Rights and Feudal Payments

To understand how England's money system worked in the Middle Ages, you need to remember that the king and the country were almost the same thing. Even though feudalism (a system where land was exchanged for loyalty and service) divided power, William the Conqueror set it up in England so the king's money rights were very strong.

First, the king's own lands were managed better. Second, the king's claims for money became more like feudal rights, which meant they were clearer in law. Third, the courts helped the king collect more fees. Most importantly, the king's increased power meant he made more money from trade.

How the King Made Money in the Middle Ages

Here are the main ways the king got money:

- Royal Lands: These were estates owned and managed by the king all over England. They included lands from old English kings and new lands taken after rebellions. If land had no owner, it went back to the king. The Domesday Book lists over 1,400 royal estates. Forests owned by the king didn't make much money, except from fines for breaking forest laws. People who rented land often paid with farm produce at first, but later paid with cash. As towns grew on royal lands, rents from townspeople became very valuable. Sometimes, towns paid a fixed yearly amount to the king.

- Feudal Payments: These were rights the king had as the main lord over his most important tenants. They included payments for knight-service (instead of actual military service), three regular feudal aids (payments for special events like the king's son becoming a knight), and payments when a new person took over a fief (land held under feudal law). The king also made money from controlling young heirs and their marriages. These payments changed depending on how powerful the king was, and people often resisted them, as shown in the demands of Magna Carta in 1215.

- Justice System: The courts were a good way for the king to make money. People had to pay fees to have their cases heard and to get official documents. Fines and settlements also added to this income.

- Vacant Church Offices: A lot of land and wealth in the kingdom was held by the church. When important church positions like bishops or abbots were empty, the king could take their income for himself for a while.

- Taxes on Jews: Until they were expelled in the 1200s, Jewish people were a very profitable source of money for the king. They were under the king's full control because they needed his permission to be money-lenders. The king could tax them whenever he wanted, sometimes taking a quarter of their property or fining them for real or supposed offenses. A special office, the Exchequer of the Jews, was even set up to handle this.

- Direct Taxes: These were special, occasional taxes. The Danegeld (a tax to pay off Viking invaders) was replaced by the carucage (a land tax based on how much land could be ploughed). Scutage developed when knights paid money instead of providing military service.

- Customs Duties: These were small fees collected at ports on goods coming in or going out of England. They were the beginning of the customs system we know today.

The way England's money system changed over time mostly involved how these different sources of income were collected. For example, a sheriff had to report to the Exchequer twice a year about the royal money collected in his county. This system worked well for about 150 years after the Norman Conquest. However, the king's personality affected how well the money was collected. For instance, popular kings like Henry I and Henry II collected much more money than less popular kings like Stephen and John.

Changes started to appear. The carucage replaced the Danegeld, which was a step towards directly taxing land based on what it produced. Also, scutage helped move England towards a money-based economy instead of payments in goods. Special taxes called tallage were sometimes put on towns in the king's lands, but these were controversial. Perhaps the most important change was the start of taxing movable goods (like personal belongings), which first happened with the Saladin tithe in 1189 and later became a general system.

During the reign of King John (1199–1216), losing Normandy and giving in to the demands of the nobles in Magna Carta meant the money system had to change. Under King Henry III (1216–1272), the nobles used Magna Carta to stop the king from using tallages unfairly. This encouraged more regular taxes on movable goods. The idea that people should agree to taxes before they are imposed led to the creation of groups representing different social classes. This is how England moved from feudal taxes to early parliamentary taxes.

Direct Taxes

Around the time Parliament started having more say in taxes, one old source of money disappeared. In 1290, King Edward I was forced by public opinion to expel the Jews from the kingdom. However, the Jews had already been taxed so heavily that they were becoming less profitable for the Exchequer. Also, the kingdom's overall wealth had grown, so their contribution was less important.

The first effects of Parliament's influence were the end of tallages on towns and the decline of scutage. Taxes on movable goods became more organized. Instead of different rates, a fixed rate was set: one-fifteenth for counties and one-tenth for towns. This was called the "fifteenth and tenth" tax. Commissioners were appointed in each county to make sure the tax was collected fairly, with clear rules about what could be taxed and what was exempt. This tax was used from 1290 to 1334, though the exact rates sometimes changed.

The growing national economy meant the king had to do more as an administrator, which increased the government's need for money. Even though the king was supposed to live off his own income, this became harder and harder. So, taxes, especially on movable goods, became more regular and direct, replacing older forms over time.

Collecting a general property tax in medieval times was hard because each local area tried to keep its assessments low. So, from 1334 onwards, a new method was used. The "fifteenth and tenth" became a fixed amount, about £39,000 in total. This amount was then divided among the counties, cities, and towns based on what they had paid before. This system lasted for centuries and was very useful because it was certain and flexible. Towns knew their total tax bill and could divide it among their citizens. The king also liked it because the "fifteenth and tenth" could be multiplied (e.g., three times the amount could be voted for three years), providing a stable income. Parliament also liked it because they could control the king's policies by deciding whether to grant or refuse these taxes. Everyone supported this system, especially as the Hundred Years' War began.

Poll Tax

Another direct tax was the poll tax, or head tax. Towards the end of Edward III's reign in 1377, the government needed money. So, a tax of fourpence was put on every person in the kingdom, except beggars and children under 14. This was followed by graduated poll taxes in 1379 and 1380, where richer people paid more. For example, dukes paid ten marks (£6 13s. 4d.), while others paid fourpence.

However, these taxes didn't raise as much money as expected. The 1380 tax, which ranged from twenty shillings to fourpence, is most famous because it was a major cause of the Peasants' Revolt in 1381.

Because of this revolt, the poll tax was mostly abandoned for almost 300 years. It was clear that the "fifteenth and tenth" was better suited for English finance because the collection system was already in place. The poll tax, on the other hand, required special agents to collect money even from the poorest people. The failure of the poll tax helped keep the direct tax system from 1334 in place.

Indirect Taxes

At the same time as direct taxes were developing, indirect taxes (like customs duties) were also growing, though more slowly. From very early times, the king had the right to charge fees on goods entering or leaving English ports. This was either because he protected traders or because of his special royal rights. For example, there was a tax on wine (one cask out of ten) and a tax of one-fifteenth or one-tenth on other goods. Magna Carta (Article 41) said that only "ancient and just customs" were allowed, forbidding new extra charges.

Parliament's influence first showed when duties on wool, woolfells (sheepskins with wool), and leather were set by Edward I's first Parliament. After the king tried to collect higher duties, the Confirmation of Charters (1297) stopped any increases beyond the amounts set in 1275. These became known as the "ancient customs."

Another attempt was made to get higher duties by making deals with merchants. Foreign traders agreed to new royal proposals, which included duties on wine, wool, hides, and wax, plus a general tax of 1.25% on all imports and exports. So, foreign merchants paid extra duties on top of the old customs. For example, they paid 50% more on wool and leather, and 2 shillings per barrel of wine (called butlerage).

These special rights for foreign merchants (laid out in the Carta Mercatoria in 1303) were probably given in exchange for accepting these higher duties. However, English merchants successfully resisted these extra charges, so their old wine tax stayed the same. Despite Parliament's objections that these new customs broke the Great Charter, they remained in force. After being stopped for a short time in 1311, they were brought back in 1322, confirmed by the king in 1328, and finally approved by Parliament in the Statute of the Staple (1353). These new customs became a permanent part of the crown's income from ports and led to further developments.

Just as old direct taxes were joined by and then absorbed into general taxes on movable goods, customs duties were followed by "subsidies" or grants from Parliament. In the 1300s, England's wealth came a lot from exporting fine wool. So, King Edward III sometimes used this to his advantage. To influence towns in Flanders, he sometimes completely banned wool exports. Other times, he put different export duties on wool, skins, and leather.

These subsidies were first imposed in 1340 and continued to be granted despite complaints. For example, in 1348, Parliament complained about a £2 export duty on wool, saying it hurt landowners by lowering wool prices. Deals between the king and merchants were forbidden and brought under Parliament's control by laws passed in 1362 and 1371. By 1371 and 1376, these taxes on wine and general goods became regular grants known as Tunnage (on wine) and Poundage (on other goods).

The Clergy

The clergy (church officials) had a special position because they claimed the right to tax themselves. So, church meetings (convocation) rather than Parliament voted on the "tenths" (taxes) on church property. Sometimes, the king ordered much higher taxes, but church taxes became less productive during the 1300s.

By the end of Richard II's reign, the shift from feudalism to a parliamentary system was almost complete. For money, the most important changes were:

- Unimportant feudal payments mostly disappeared or were greatly reduced. This happened quite early in England.

- The royal lands, though still valuable, had lost some of their importance.

- To make up for this, direct taxes on property became a quick way to meet the government's growing needs. The way these taxes were collected became well-known, and unsuccessful ideas like the poll tax were stopped.

- The growth of import and export duties (old and new customs, plus subsidies) provided a large part of the needed money. In just over 300 years, without violence, the main sources of government income had completely changed in value and organization.

New Ways to Raise Taxes

The time of the Lancastrian kings (1399–1471) saw new kinds of direct taxes. The main tax, the "fifteenth and tenth," wasn't working as well because towns were declining, so the government had to give more allowances, reducing its yield. To make up for this, a 5% land tax was introduced in 1404, mainly for large landowners. A lower rate of 1.66% was applied to less wealthy people in 1411. A house tax appeared in 1428, and taxes on knights' fees and other freeholds were also tried. In 1435 and 1450, a graduated income tax was used, meaning richer people paid a higher percentage. This showed the need for more money. At this time, England started to look at tax ideas from other countries like France and Italy.

For indirect taxes, income seemed to drop at first. Subsidies were granted for specific periods. However, after Edward IV became king, Parliament voted a special "tenth" tax in 1472 for military needs. But it didn't raise enough money, forcing the king to go back to older ways of getting funds.

Extra taxes on foreigners were collected under both Lancastrian and Yorkist kings, but they didn't bring in much money. King Edward IV's most unique idea was "benevolences," which were payments wealthy people were asked to give the king. These were supposed to be voluntary but were actually forced. They later became a big complaint against the king that Parliament had to fight.

The Tudor period (late 1400s to early 1600s) brought bigger financial changes as countries became more centralized. Governments needed larger armies and navies, and more expensive ways to run the country. Economic ideas like mercantilism (focusing on national wealth) affected both foreign policy and money matters. The king's personality also played a big role. For example, Henry VII was very keen on filling the royal treasury after the Wars of the Roses. He strictly enforced old feudal payments instead of asking Parliament for help. He also set up a "Chamber Finance" system that was faster than the old Exchequer. In contrast, Henry VIII was very extravagant, while Elizabeth had a very different money policy. Also, the desire for a strong foreign policy and encouraging local industries sometimes meant that getting the most money wasn't the only goal.

The entire economy was seen as a tool to make the country more powerful. This more complex policy, along with new influences like the discovery of America, the Renaissance, and the Reformation, made the money problems of the 1500s very interesting.

The king's first source of income was the crown lands. These lands sometimes got smaller due to gifts to the king's family and friends, but they also grew through lands being returned to the crown or taken from rebels. However, crown lands were not a flexible source of income. They became much less valuable starting in the 1400s, especially under Henry VI, due to spending pressures and mismanagement.

Edward IV didn't make the most of the many estates that returned to the crown during the Wars of the Roses. The biggest chance to gain land came from Henry VIII dissolving the monasteries and guilds. Much of this property went to nobles and officials, and the rest was given away during his children's reigns. This meant that land and rents continued to become less important for government income. Feudal payments also became less significant, even though there were occasional attempts to enforce them strictly. The Tudor monarchs, who relied on popular support, tended to encourage collecting other types of payments instead of relying heavily on taxes. The old right of purveyance (where the king could buy goods at a low price) was also used less and finally abolished in 1660.

In the 1500s, getting extra money from crown lands and the king's special rights was fully exploited. However, these were now much less profitable. The political and social situation increasingly showed that direct taxes needed to become the main source of government income. The government needed more money to run the growing state and because prices were rising due to more precious metals coming into the country.

One form of direct taxation from Edward III's reign remained: the "fifteenths and tenths" continued to be voted in, but attempts to introduce new methods failed. In 1488, a military tax based on an earlier failed tax only brought in a little over a third of what was expected. This failure stopped Henry VII from trying more new taxes. Henry VIII's foreign policy, especially his expensive French expedition, led to a graduated head tax in 1513. This also brought in much less than expected. But these failures paved the way for a more effective direct tax: a general tax (1514) on land and goods, which started modestly at 2.5%. However, it was soon raised to 4 shillings per pound on land and 2 shillings 8 pence per pound on goods. This new tax, called the "subsidy," became the main way Parliament granted money to the king, making the old "fifteenth and tenth" less important.

The subsidy became the standard way of granting money under both the Tudors and Stuarts. However, it gradually changed, becoming less flexible over time, much like its predecessor. Each subsidy was worth about £100,000 in the mid-1500s, but by the end of the century, it had fallen to only £80,000. The clergy also voted their own taxes, which amounted to £20,000. Usually, Parliament voted for a number of "fifteenths and tenths" plus subsidies. For example, Elizabeth I's first Parliament voted her two "fifteenths and tenths" plus one subsidy, totaling about £160,000. During wars, like the attempted invasion by the Spanish Armada, more "fifteenths, tenths, and subsidies" were granted. The history of the subsidy shows how it became a fixed sum over time, setting a pattern for later land and property taxes.

Under the Tudors, port duties (taxes on wool, hides, leather, plus "tunnage" on wine and "poundage" on other goods) were granted to each king or queen for life. These, along with other traditional customs, provided a lot of money for the crown. This showed how much more powerful and popular the monarchy had become, a big change from the suspicious Parliaments of the Plantagenet and Lancastrian times. However, increasing the duty on Malmsey wine in 1490 was more about revenge against the Venetians (who had restricted English trade) than about raising money. Increases were later put on French wine for similar reasons.

Even though restrictions on imports and exports were more about economic policy than money, they indirectly increased control at the ports. However, losing Calais in 1558 disrupted the customs system by cutting off a key customs revenue center. This might have also led to a new way of valuing duties. In 1558, fixed values were used for the first time and listed in a "book of rates." Stricter reforms followed, especially against smuggling and fraud by corrupt officials. Despite these reforms, collection costs remained very high throughout the Tudor period.

Just as the subsidy followed old and new customs in the 1300s, in the 1500s, taxes imposed by the king's special rights also added to the parliamentary subsidy. However, these were used most heavily in the next century. Another important sign for the future of indirect taxation was the granting of monopolies (exclusive rights) to inventors, producers, and traders. When these affected important goods, they worked like taxes collected by private individuals. Although the king's profits from these were small, they raised prices and caused unhappiness. Promises to fix this finally came after a big debate in 1601.

It's fair to say that one of the biggest fights between the Stuart kings and Parliament was about money. Taxation was definitely a point of conflict. From the time James I became king in 1603 until the start of the Civil War in 1642, the legal basis of indirect taxes (port duties in the John Bates case) and direct taxes (the famous Ship Money case involving John Hampden) was challenged. Parliament also debated monopolies, subsidies, and how the money from them should be used. Despite these conflicts, the overall system was growing and adapting to the state's increasing needs.

Parliament's direct grants to James I were much larger than in earlier reigns. For example, in 1606, they voted for "fifteenths and tenths" and several subsidies. However, the king's attempts to get money by using his special rights naturally made Parliament less generous. The last "fifteenth and tenth" was voted in 1624, after which this old tax disappeared, leaving only the subsidy. Even with Charles I's forceful policies, five subsidies were voted after the Petition of Right was accepted, and even the Long Parliament made similar grants. Near the start of the Civil War, Parliament also granted the king a graduated head tax.

Other direct taxes were used without Parliament's approval. Old feudal payments were enforced very strictly through special courts like the Star Chamber. James had tried a French idea of selling titles of honor, and both he and his son used "benevolences" until the Petition of Right made them illegal. But the most serious new tax was Ship Money, which Charles was forced to collect because he wanted to rule without Parliament. This tax showed how clever the king's advisors were at finding ways for him to rule alone. The first collections brought in over £100,000, and five more collections (1634–1639) brought in an average of £200,000 each. Like the benevolence, Ship Money was declared illegal in 1641.

The fight over monopolies, which Elizabeth had stopped, started again under James. It finally ended with the Statute of Monopolies (1624), which said such grants were completely invalid. Some exceptions (like for soap makers) allowed money to be raised by what was actually an early form of excise tax (an internal tax on goods). Plans for a general excise tax were also discussed, especially as a replacement for feudal payments. In the early 1600s, customs duties steadily increased from £127,000 in 1604 to almost £500,000 in 1641. This was due to the growth of English trade, new "books of rates" (1608 and 1635) that set higher values, and the inclusion of new goods like wine, currants, tobacco, and sugar.

One development was the widespread use of the "farming system," where the right to collect taxes was sold to private individuals. This was copied from France. There were different types of "farms" for different goods. Constitutionally, Parliament refused to grant Charles I the lifetime customs subsidies that had been given to James, because of Charles's harsh policies. However, between 1628 and 1640, all customs revenue was raised only by the king's special right. This was finally stopped by The Tunnage and Poundage Act of 1641, which made such extra-parliamentary customs illegal.

In short, the way England raised money changed almost completely from the Norman Conquest to the start of the Great Rebellion. The king no longer supported himself, and the royal lands and feudal rights became much less important. They were replaced by direct and indirect taxes.

The Civil War and the Commonwealth

A big change in English financial history happened during the Civil War and the Commonwealth period (1642-1660), when most feudal systems were abandoned. This time, including the Interregnum (the period without a king, 1649–1660), marked a new beginning. At the start of the war, both sides had to rely on voluntary donations. People melted down silver and ornaments, and supporters gave useful goods to both the king and Parliament. However, even with subsidies and a poll tax, collecting money was hard, so new methods were needed. Unlike the loose management of earlier subsidies, direct taxes were now assessed monthly at a fixed rate and collected under strict rules. This made them more systematic and fair than before.

Despite its origin, this monthly assessment became the model for later property taxes. It brought in over £32 million during this period, showing how important it was. Smaller ideas, like a weekly meal tax, showed Parliament's difficulties but were not very important. Because Parliament controlled the sea and the main ports, it could also control customs revenue. It changed duties again, getting rid of the wool subsidy and adjusting general customs with a new "book of rates." A more extensive tariff (list of duties) was adopted in 1656, and various restrictions, in line with the economic ideas of the time, were enforced. French wines, silk, and wool were exempt from 1649 to 1656.

Even more revolutionary was the introduction of the excise tax, or internal duties on goods. Elizabeth, James I, and Charles I had hesitated to do this. Starting in 1643 with duties on ale, beer, and spirits, it soon spread to meat, salt, and various textiles. Meat and domestic salt were exempted in 1647, and the tax became firmly established under special commissioners. Powers were given to allow private individuals to collect the tax. In 1657, bids for both excise and customs amounted to £1,100,000. Confiscations of church and royalist lands, feudal charges, and special collections helped raise a total of £83 million during the nineteen years of the revolution.

Another change was moving the Exchequer to Oxford, but the real money management was done by the committees that ran Parliament's affairs. Under Oliver Cromwell, the Exchequer was re-established in 1654 in a way that suited the new financial system, with commissioners in charge of the Treasurer's office.

The Restoration and Beyond

After the Restoration (when the monarchy was brought back in 1660), the money system needed a complete overhaul. Feudal land ownership and payments, along with the king's rights of purveyance (buying goods cheaply) and pre-emption (buying first), could not be brought back. Careful study showed that before the Civil War, the king's yearly income was just under £900,000, but the restored monarchy would need about £1,200,000 per year. So, the House of Commons set about raising this amount. An inherited excise tax on beer and ale was voted in to make up for the lost feudal payments, while temporary excise taxes were put on spirits, vinegar, coffee, chocolate, and tea.

All differences between old and new customs and subsidies had disappeared under the Commonwealth. The General or Great Statute (1660) set a scale of duties: 5% on imports and exports, with special duties on wines and woollen cloths, along with a new "book of rates." A house tax, based on the number of hearths (fireplaces), was introduced in 1662, similar to French taxes. Poll taxes were used for emergencies, as were the last subsidies, voted in 1663 and then abandoned forever. Licenses for retailers and fees on legal proceedings also helped raise money. In the later years of Charles II and the short reign of his successor, the government struggled to keep up with increasing spending.

The Commonwealth's tax assessments were used again several times. Indirect taxes became stricter with extra duties on brandy, tobacco, sugar, French linens, and silks. A major development was putting customs (1670) and excise (1683) in the hands of special commissioners, instead of selling the right to collect them to private individuals. This more modern approach was also seen in the greater care taken with customs administration. Dudley North was a very important customs commissioner during this time. Also, the start of the national debt can be traced to the Stop of the Exchequer in 1672, when the government delayed paying back short-term loans to bankers indefinitely.

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 completed the work of the Long Parliament in both constitutional and financial ways. Its main effects on money were:

- Control of money management moved from the king's chosen people to officials controlled by Parliament.

- Money was then used only for the purposes Parliament approved.

- Different ways of raising money, especially indirect taxes, grew quickly.

- The national debt grew, and an effective banking system was created. (Most of the 1700s was spent dealing with these changes.)

The government of William III faced the cost of war while also needing to calm unrest at home. To figure out the necessary income, a report was made showing tax receipts of £1,100,000 during peacetime and £1,800,000 during wartime. Parliament believed £1,200,000 per year would be enough for the kingdom's normal needs. They introduced the Civil List, setting aside £600,000 for certain fixed payments and leaving the rest for other state needs. The "hearth money" tax was very unpopular, so it was abolished, even though it brought in £170,000. Additionally, more excise duties were voted in for William and Mary's lifetimes, plus more customs duties, though these were only for a limited time. However, these incomes were still not enough for the costs of war, so new taxes were created, and older ones were brought back.

A series of poll and head taxes were imposed between 1689 and 1698 but were then abandoned because they were as unpopular as "hearth money." In 1688, monthly tax assessments were introduced, followed by income tax, and then twelve-monthly assessments in 1690 and 1691. This prepared the way for the property tax of 1692, which charged 4 shillings per pound on real estate, offices, and personal property. However, old collection problems meant it mostly became a land tax, which is what it was generally called. The 4-shilling rate brought in £1,922,712, but this amount decreased in later years. To make up for this, a fixed amount of nearly half a million pounds (a 1-shilling rate) was adopted in 1697. This amount was divided among towns and counties and stayed largely the same until 1798. In 1696, houses were taxed at 2 shillings each, with higher rates for extra windows. This was the beginning of the window tax. Licenses on peddlers and a temporary tax on company stocks completed these taxes.

Following Holland's example, stamp duties (taxes on official documents) were adopted in 1694 and expanded in 1698. Large amounts were added to the excise tax. Breweries and distilleries were taxed, and important goods like salt, coal, malt, leather, and glass were included as taxable items (though the last two were later removed). Similarly, customs rates were also increased. In 1698, the general 5% duty was raised to 10%. French goods faced extra taxes, first 25%, then 50%, while goods from other countries were charged less. Also, spirits, wines, tea, and coffee were taxed at special rates.

The growth of the money system can be seen from the fact that during the relatively short reign of William III (1689–1702), the land tax brought in £19,200,000, customs raised £13,296,000, and excise £13,650,000, totaling about £46 million. In the last year of his reign, these taxes brought in over £3.5 million. Regular export duties were removed only for domestic woollen goods and corn, for special policy reasons.

Just as remarkable as the growth of income was the sudden appearance of public loans. In earlier times, a ruler would save money, or use jewels or customs income as collateral for loans. Edward III's dealings with bankers from Florence are well known. But it was only after the Revolution that two key things needed for a permanent national debt were in place:

- The government was responsible to the people.

- There was an effective market for borrowing money.

By the end of the war in 1697, a debt of £21.5 million had been created, and over £16 million was still owed when William III died. Connected with the public debt at that time was the founding of the Bank of England. It increasingly became the main agent for handling the government's income and spending, although the Exchequer continued to exist until 1834 as an old-fashioned institution. So, by the end of the 1600s, new ideas from the Civil War had created all the parts of a modern money system. Spending, income, and borrowing had essentially developed into their current forms. Later changes were mostly about increasing amounts, improving procedures, and better ideas about public policy.

Generally speaking, the 1700s and 1800s had several distinct financial periods. From William III's death in 1702 to the start of the Revolutionary War with France in 1793, there were four wars lasting nearly 35 years. The long, peaceful time under Walpole can be compared to the shorter peaceful periods after each war. From the start of the war with France to the Battle of Waterloo, there were almost twenty years of continuous war. The next forty years of peace ended with the Crimean War (1854–56), and another forty years of peace ended with the Second Boer War (1899–1902). During this time, older ideas like mercantilism gave way to protectionism, which then led to the gradual adoption of free trade. During each war, taxes (especially indirect taxes) and debt increased. Financial reform usually happened during peacetime. Important financial ministers included Walpole, the younger Pitt, Peel, and Gladstone.

By looking at the main sources of income, it's easy to understand the progress made in later years:

- The land tax, set up firmly in 1692, was the main direct tax of the 1700s. Its rate varied from 1 shilling (in 1731) to 4 shillings (in most war years). In 1798, Pitt changed it into a fixed charge on land, reducing its yield significantly over time. Other major increases in other taxes also reduced its importance.

- Excise duty grew quickly in the 1700s. Most everyday goods were permanently taxed. In 1739, excise duties brought in £3 million, a sum that later rose to £10 million. This continued growth was due to more items being taxed and the country's increasing consumption.

- Customs duties were also very useful, with even bigger increases. The general 10% rate of 1698 became 15% in 1704, then 20% in 1748, and 25% in 1759. Customs duties on special items like tea also increased. The American Revolutionary War led to a further 10% increase plus special extra duties on tobacco and sugar. By 1784, customs revenue had risen to over £3 million.

However, two other things must be considered:

- The extremely strict duties and bans were mainly aimed at French trade.

- There was a lack of care in figuring out the best tax rate for each duty to get the most money.

Jonathan Swift's famous saying that "in the arithmetic of customs, two and two sometimes made only one" was very true in England at this time. Smugglers caused the loss of much of the country's foreign trade revenue, even though efforts were made to reform the system. Walpole made several useful changes by getting rid of general duties on exports and some on imported raw materials like silk and timber. His most ambitious plan to store wine and tobacco in warehouses to help exporters failed, however, because people thought it was the start of a general excise tax. Nevertheless, his reduction of the land tax and his earlier plan to manage debt are notable, as is his determination to keep peace, which was also helped by his money reforms.

Pitt's government from 1783 to 1792 was another period of improvement. He simplified customs laws (1787), reduced the tea duty to almost one-tenth of its previous amount, made a good trade agreement with France, and tried to arrange trade with Ireland. This shows that Pitt would have introduced many free trade measures earlier if he had enjoyed ten more years of peace.

One financial problem that caused interest and even alarm was the rapidly increasing national debt. Each war added greatly to the debt, and peaceful periods showed little reduction. It rose from £16 million in 1702 to £53 million by the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). In 1748, it reached £78 million, and by the end of the Seven Years' War, it was £137 million, only to exceed £238 million by the time the American colonies became independent. Fear of national bankruptcy led to the idea of a sinking fund (money set aside to pay off debt), but in this case, Pitt's usual wisdom failed him. Influenced by Richard Price's theory, he adopted a policy of setting aside special sums for debt reduction without truly having a surplus of money.

Income Tax

The revolutionary and Napoleonic wars marked an important stage in English finance. The country's resources were stretched to the limit, and heavy taxes were placed on everyone. In the early years of the war, borrowing helped the government avoid the most oppressive taxes. But as time went on, every possible method was used. Taxes on houses, carriages, servants, horses, and plate had been raised by 10% steps until, in 1798, their total charge was increased three to five times for the rich under a plan called "triple assessment."

This plan didn't work as well as expected (it didn't produce the estimated £4.5 million), which led to the most important development: the introduction of income tax in 1798. Although it grew out of the "triple assessment," income tax was also connected to the permanent settlement of the land tax. You can trace the progress of direct taxation from the scutage of Norman times, through the "fifteenth and tenth," the Tudor subsidies, the Commonwealth's monthly assessments, and the 1700s land tax, to the income tax used by Pitt. After a break, it was brought back by Peel in 1842. However, its immediate yield was less than expected (£6 million out of £7.5 million). Nevertheless, by changing how it was assessed (from a general declaration to returns under several categories), the tax became, at first 5% and then 10%, the most valuable part of the government's income. In 1815, it contributed 22% of total receipts, or £14.6 million out of £67 million. If it had been used at the beginning of the war, it would have prevented many of the government's financial problems.

The window tax, which continued throughout the 1700s, was supplemented during the American War by a tax on inhabited houses. Also, probate duty (a tax on inherited property) had been gradually raised during the 1700s, and legacy duty (a tax on inherited money) was introduced in 1780, which was moderate and didn't affect land. Although direct and quasi-direct taxes had increased dramatically, their growth was overshadowed by that of excise and customs duties. With each year of war, more items were taxed, and tax rates were raised.

The saying, "wherever you see an object, tax it," seemed to guide financial policy in the early 1800s. Food, drinks, industrial materials, manufactured goods, and business transactions were taxed in almost all their forms. For example, salt was taxed at 15 shillings per bushel, sugar at 30 shillings per hundredweight, beer at 10 shillings per barrel, and tea at 96% of its value. Timber, cotton, raw silk, hemp, and bar iron were also taxed, as were leather, soap, glass, candles, paper, and starch.

Despite the need for money, many customs duties were designed to protect local industries, which meant they brought in relatively small amounts of money. For example, import duty on salt in 1815 brought in only £547, compared to £1,616,124 from excise tax. Some duties, like that on gloves, were abandoned because they didn't bring in enough money. The financial system generally suffered from being too complicated and lacking clear principles. In peacetime, Pitt was willing to follow the ideas of The Wealth of Nations. However, the pressure of war forced him and his successors to use any taxes that would bring in money without upsetting people too much. Along with taxation, debt increased. For the first ten years, additions averaged £27 million per year, bringing the total to over £500 million.

By the end of the war in 1815, the total debt reached over £875 million. Smaller annual increases resulted from using more effective taxes, especially income tax. Increasing trade levels also helped, and the import of items like tea grew with the population. For example, the 96% tea duty brought in no less than £3,591,000 in 1815. However, by that time, the tax system had reached its limit. Further expansion (except by directly taking property) was hardly possible. The war ended victoriously just when it seemed the country couldn't endure it any longer.

A special part of the English money system is how it related to the money systems of territories connected to the English crown. The Exchequer might have come from Normandy, and wherever England ruled, the methods used at home seemed to be adopted. When England lost its French lands, these older cases disappeared. However, Ireland had its own exchequer, and Scotland remained a separate kingdom. The 1700s brought a remarkable change. One goal of the union with Scotland was to ensure free trade throughout Great Britain, and the two money systems were combined. Scotland was given a very small share of the land tax (less than one-fortieth) and was exempt from certain stamp duties. The attempt to apply selected taxes (custom duties in 1764, stamp duties in 1765, and finally the tea duty in 1773) to the American colonies showed a move towards what would now be called "imperialist finance."

The complete plan for a British empire, outlined by Adam Smith, was clearly driven by financial reasons. Despite this movement failing in the case of the American colonies, it succeeded with Ireland by the end of the century. However, separate financial departments remained until after the Napoleonic War, and some tax differences still exist. With the combining of the English and Irish exchequers and the shift from war to peace, the years between 1815 and 1820 marked a clear step in the country's financial development. The related change in the Bank of England, by resuming special payments, supports this view. Also, political conditions were undergoing a revolution that affected finance. The landed gentry, though powerful at the moment, now faced competition from the wealthy manufacturing areas of northern England. Ideas from economic discussions also began to influence the nation's financial policy, with statesmen and officials paying attention to rules about how to manage, tax, and borrow money.

These influences can be seen in the main adjustments and changes that followed the end of peace. Relieved from the huge spending of the previous years, the government felt it had to propose reductions. Wisely, it was decided to keep the income tax at 5% (half the previous rate) and also remove some war duties on malt and spirits. However, popular feeling against direct taxation was so strong that the income tax had to be completely removed, which seriously hurt the government's finances in the following years. For over twenty-five years, the income tax was not used, to the great detriment of the revenue system. Its return by Peel in 1842, intended as a temporary measure, proved its value as a permanent tax; it has continued and expanded considerably since. Both the excise and customs taxes at the end of the war had some of the worst flaws of bad taxation. The excise tax had the negative effect of limiting industrial progress and hindering new inventions.

The prices of raw materials and auxiliary substances used in industry were often raised. The duties on salt and glass especially showed the bad results of the excise tax. New processes were hindered, and old routines were made compulsory. Customs duties were even more restrictive of trade; they practically excluded foreign manufactured goods and were both costly and often didn't bring in much money. As George Richardson Porter showed in Progress of the Nation (1851), the really profitable customs taxes were few. Less than twenty items contributed more than 95% of the revenue from import duties. Taxes on transactions, mainly collected through stamps, were poorly graded and not comprehensive enough.

From the standpoint of fairness, the criticism was equally clear. The heaviest tax burden fell on the poorer classes. Landowners avoided paying taxes on the property they held under the state, and other people were not taxed according to their ability to pay, which had long been recognized as the proper standard.

The unfairness in tax distribution has been lessened, if not removed, by the great development of:

- The income tax.

- The death or inheritance duties.

Starting at 7 pence per pound (1842–1854), the income tax was raised to 1 shilling 4 pence for the Crimean War, and then continued at varying rates, reduced to 2 pence in 1874, then rose to 5 pence, then in 1894 to 8 pence, and by 1909 seemed to be fixed at a minimum of 1 shilling, or 5% on income from property. The amount of money collected per penny of tax has risen almost continuously. From £710,000 in 1842, it now exceeds £2,800,000, although the exemptions and reductions are much more extensive. In fact, all incomes of £3 per week are completely tax-free (£160 per year is the exact exemption limit), and an income of £400 earned from work pays less than 5.5 pence per pound, or 2.25%. The great productivity of the tax is equally remarkable. From £5,600,000 in 1843 (with a rate of 7 pence), the return rose to £32,380,000 in 1907–1908, having been at a maximum of £38,800,000 in 1902–1903, with a tax rate of 6.25%. The income tax thus provides about one-fifth of the total revenue, or one-fourth of that obtained by taxation.

Several basic questions about money are connected with income taxation and have been addressed by English practice. Small incomes claim lenient treatment; and, as mentioned above, this leniency in England means complete freedom. Also, earned incomes seem to represent a lower ability to pay than unearned ones. Long refused for practical reasons (by Gladstone and Lowe), the concession of a 25% reduction on earned incomes of £2,000 and under was granted in 1907. The question of whether savings should be exempt from taxation as income has (with the exception of life insurance premiums) been decided in the negative. Allowances for depreciation and cost of repairs are partially recognized.

Far more important than these special problems is the general one of increased tax rates on large incomes. Up to 1908-1909, the tax above the reduction limit of £700 remained strictly proportional, but opinion showed a clear tendency in favor of extra rates or a supertax on incomes above a certain amount (e.g., £5,000), and this was included in the budget of 1909–1910.

Estate Duty

Closely related to the income tax is the estate duty, with its accompanying legacy and succession duties. After Pitt failed to pass the succession duty in 1796, no change was made until Gladstone introduced a duty on land and settled property in 1853, similar to the legacy duty on personal property. Aside from some minor changes, the really vital change was the expansion in 1894 of the old probate duty into a comprehensive tax applicable to all the possessions of a deceased person. This Inheritance Tax (to give it its scientific title) acts as a complementary property tax, and is thus an addition to the contribution from incomes derived from large properties.

By graduation, the charges on large estates in 1908-1909 (before the proposal for further increase in 1909–1910) came to 10% on £1,000,000, and reached the maximum of 15% at £3,500,000. From the various forms of inheritance taxes, the national revenue gained £14,500,000, with £4.5 million as a supplementary yield for local finance.

The expansion of direct taxation is clear when comparing 1840 with 1908. In 1840, the probate and legacy duties brought in about one million pounds; the other direct taxes, even including the house duty, did not raise the total to £3,000,000. In 1908, the direct taxation of property and income supplied £51,500,000, or one-third of the total receipts, compared to less than one-twentieth in 1840.

But although this wider use of direct taxation (a characteristic of European finance generally) reduced the relative position of commodity taxation, there was a growth in the absolute amount obtained from this category of duties. There were also considerable alterations, resulting from changes in views regarding financial policy. At the close of World War I, the excise duties were at first retained, and even in some cases increased. After some years, reforms began. The following articles, among others, were freed from charge: salt (1825); leather and candles (1830); glass (1845); soap (1853); and paper (1860). The guiding principles were:

- Removing raw materials from the list of goods subject to excise tax.

- Limiting the excise tax to a small number of productive articles.

- Placing most (practically nearly all) of this form of taxation on alcoholic drinks.

Aside from breweries and distilleries, the excise tax had little scope for its work. The large revenue of £35,700,000 in 1907-1908 was derived half from spirits (£17,700,000), over one-third from beer, while most of the remainder was obtained from business taxation in the form of licenses, the raising of which was one of the features of the budget in 1909. As a source of revenue, the excise tax could be regarded as equal to the income tax, but less reliable in times of economic downturn.

Valuable as the reforms of the excise tax were after 1820, they were insignificant compared to the changes in customs. The particular circumstances of English political life have perhaps led to too much emphasis being placed on this particular branch of financial development. Between 1820 and 1860, the customs system was transformed from a highly complicated arrangement of duties, pressing severely on nearly all foreign imports, into a simple and easily understood set of charges on certain specially selected commodities. All favors or preferences to home or colonial producers disappeared.

In financial terms, all duties were imposed for revenue only, and estimated based on their productivity. An alignment between the excise and customs rates necessarily followed. The stages of development under the guidance of Huskisson, Peel, and Gladstone are commonly regarded as part of the movement for Free Trade, but the financial impact of the alteration is understood only by remembering that the duties removed by tens or by hundreds were quite trivial in yield, and did not involve any serious loss to the revenue.

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of English customs in the 1800s was the steadiness of the receipts. Despite trade depressions, discussion was likely to be felt in the treatment of the financial policy of the nation. Rules about the proper system of administration, taxation, and borrowing came to be noticed by statesmen and officials.

The exemption of raw materials and food; the absence of duties on imported, as on home manufactures; the selection of a small number of articles for duty; the rather rigorous treatment of spirits and tobacco, were the salient marks of the English fiscal system which grew up in the 1800s. The part of the system most criticized was the very narrow list of dutiable articles. Why, it was asked, should a choice be made of certain objects for the purpose of imposing heavy taxation on them?

The answer has been that they were taken as typical of consumption in general and were easily supervised for taxation. Moreover, the element of discouraging luxury is introduced by the policy of putting exceptionally heavy duties on spirits and tobacco, with lighter charges on the less expensive wines and beers.

Ease of collection and distribution of taxation over a larger class appear to be the grounds for the inclusion of the tea and coffee duties, which are further supported by the need for obtaining a contribution of, roughly speaking, over half the tax revenue by duties on commodities. The last consideration led, at the beginning of the 1900s, to the sugar tax and the temporary duties on imported corn and exported coal.

As a support to the great divisions of income tax, death duties, excise, and customs, the stamps, fees, and miscellaneous taxes are of decided service. A return of £9,000,000 was secured by stamp duties. So-called non-tax revenue largely increased, owing to the extension of the postal and telegraphic services. The real gain was not so great, as out of gross receipts of £22,000,000 over £17,500,000 is absorbed in expenses, while the carriage of ordinary letters seems to be the only profitable part of these services. Crown lands and rights (such as vintage charges) were of even less financial value.

Images for kids

-

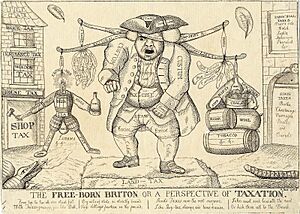

'The free-born Briton or a perspective of taxation', a satirical print of 1786: an angry John Bull carries a double yoke loaded up with items subject to taxes, customs, excise or stamp duties. The land he walks on is taxed, as is the nearby house, while the church proffers parochial taxes and state taxes.

See also

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |