History of the State of Palestine facts for kids

The history of the State of Palestine is about how the State of Palestine was created and developed in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. For many years, different ideas were suggested for how to divide the land, but everyone couldn't agree.

In 1947, the United Nations (UN) voted on a plan to divide the land. Jewish leaders accepted parts of this plan, but Arab leaders did not. This disagreement led to a war in 1947-1949. In 1948, the state of Israel was formed on some of the land.

After the 1948 war, the Gaza Strip was controlled by Egypt, and the West Bank was ruled by Jordan. But in 1967, during the Six-Day War, Israel took control of both areas. Since then, there have been many ideas for creating a Palestinian state. One idea was for a single state where both Arabs and Jews would live together. Israel rejected this idea.

Today, the main idea is for a two-state solution. This means having two separate states: Israel and a Palestinian state. The Palestinian state would be in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. These areas have been under Israeli control since 1967.

Contents

Early History and British Rule

The Ottoman Empire Era

Before World War I, the land we now call Palestine was part of the large Ottoman Empire. After the war, the Ottoman Empire broke apart. European countries like Britain and France then divided many of its regions into new states. These new states were managed under special agreements called "mandates" from the League of Nations.

Syria and Lebanon came under French control. Iraq and Palestine were given to the British. Most of these new states became independent fairly easily. But Palestine remained a difficult situation.

After World War II, a strong feeling of Arab nationalism grew. Many Arabs wanted to create a single, independent Arab state.

The British Mandate Period

In 1917, the British government made a statement called the Balfour Declaration. It said Britain supported creating a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine. Many Jews around the world were excited by this.

However, Palestinian and Arab leaders were against it. They said it broke promises Britain had made to the Sharif of Mecca in 1915. Those promises were made in exchange for Arab help fighting the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

Over the years, many different ideas were suggested to solve the problem. These included an Arab state, a Jewish state, or even a single state for both.

Arab leaders also believed Palestine should join a larger Arab state in the Middle East. But these hopes faded as Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan became independent. Meanwhile, the conflict between Arabs and Jews in Palestine grew.

Arabs began to ask for their own state in Palestine. They also wanted Britain to stop supporting a Jewish homeland and to limit Jewish immigration. As more Jews moved to Palestine, this movement grew stronger. The British tried to find a balance by creating laws called "White Papers" that limited Jewish immigration and land sales.

Early Promises: McMahon–Hussein Correspondence (1915–1916)

During World War I, British officials talked with Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, an Arab leader. They discussed an alliance against the Ottomans. In 1915, a British official named Henry McMahon sent a letter to Hussein. This letter, part of the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence, said Britain would recognize Arab independence in many areas.

However, the letter also listed some areas that would be excluded from Arab control. One of these was "Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo." This part caused a lot of problems later. The Arabs believed this meant Palestine would be part of their independent area. But the British later said it meant Palestine was excluded.

Britain also made a secret agreement with France in 1916, called the Sykes–Picot Agreement. This agreement divided the Middle East into British and French zones of influence, which went against some of the promises made to the Arabs.

Despite Arab objections, Britain was given the Mandate for Palestine by the League of Nations. This mandate divided the land into two parts: Palestine (west of the Jordan River) and Transjordan (east of the Jordan River). The goal of the mandate was to create a "Jewish National Home" in Palestine, but this goal did not apply to Transjordan, which became independent earlier.

The Peel Commission (1936–1937)

During a major Arab uprising in Palestine (1936-1939), the British government formed the Peel Commission. This commission suggested dividing Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state.

The plan suggested a small Jewish state in the Galilee and along the coast. The rest would be an Arab state, joined with Transjordan. Jerusalem and Jaffa would be a special British area. The commission also suggested moving Arabs from Jewish areas and Jews from Arab areas, even if it meant using force.

Jewish leaders rejected the plan but were open to more talks. Arab leaders rejected it completely. The British government eventually dropped the idea in 1938.

In 1939, the British government issued another "White Paper." This time, they abandoned the idea of dividing Palestine. Instead, they suggested Jews and Arabs share one government and put strict limits on Jewish immigration. But because of World War II starting, and opposition from both sides, this plan also failed.

World War II (1939–1945) and the Holocaust (the mass murder of Jews by the Nazis) made the call for a Jewish homeland even stronger.

The Arab League and Palestinian Demands (1945)

After World War II, the Arab League was formed by Arab nations. They wanted Palestinian Arabs to be part of the League. They stated that Palestine's independence should be recognized, even though it wasn't yet fully in control of its own future.

In 1945, the Arab League helped create the Arab Higher Committee. This group became the main representative body for Palestinian Arabs under British rule.

In 1947, the Arab Higher Committee clearly stated its demands to the United Nations:

- Stop all Jewish immigration to Palestine.

- Stop all land sales to Jews.

- End the British Mandate and the Balfour Declaration.

- Recognize Palestine as an independent Arab state, with rights for Jewish minorities.

The 1947 UN Partition Plan

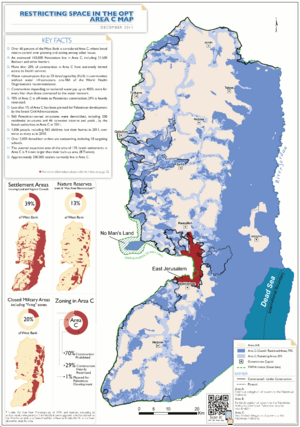

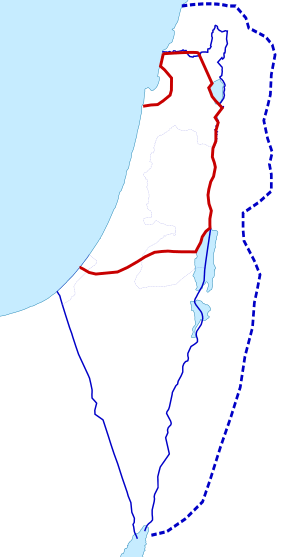

Boundaries defined in the 1947 UN Partition Plan for Palestine:

Armistice Demarcation Lines of 1949 (Green Line):

In 1947, the United Nations (UN) stepped in to find a solution for Palestine. The UN created a special committee (UNSCOP) to study the issue.

On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly voted to adopt the Partition Plan. This plan suggested dividing Palestine into two independent states: one Arab and one Jewish. The city of Jerusalem and Bethlehem would be a special international area, managed by the UN.

The plan also included ideas for economic cooperation between the two proposed states. It aimed to protect religious and minority rights. The UN hoped this plan would solve the conflict between Jewish and Arab nationalist movements. It also aimed to help Jews who had been displaced by the Holocaust. The plan called for British forces to leave by August 1948, and for the new states to be established by October 1948.

Leaders of the Jewish Agency for Palestine accepted parts of the plan. However, Arab leaders refused it.

Civil War (1947–1948)

Soon after the UN vote, fighting broke out between Arab and Jewish communities in Palestine. This was less than six months before the British Mandate was set to end.

By May 14, 1948, when Israel declared its independence, the Jewish forces had won a major victory. Palestinian Arab military power was weakened, and many Arabs left or were forced out of the fighting areas. The Jewish defense force, the Haganah, grew into an army. It was able to defend itself and gain support from other countries.

On April 12, 1948, the Arab League announced that Arab armies would enter Palestine to "rescue it." They said these actions would be temporary and not an occupation.

After the 1948 War

The 1948 Arab–Israeli War

On May 14, 1948, as the British Mandate ended, Jewish leaders declared the creation of the State of Israel. The very next day, Arab countries declared war on the new state. This marked the beginning of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.

Armies from neighboring Arab states entered the former Mandate territories. However, some of these Arab leaders had their own plans for Palestine. As a result of the war, Palestine "disappeared from the map" as a single entity.

Egypt took control of the Gaza Strip. In September 1948, Egypt formed the All-Palestine Government in Gaza. This government declared an independent Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital. Several Arab countries recognized it, but Jordan and non-Arab countries did not. This government had little real power and was mostly controlled by Egypt. In 1959, Egypt's president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, dissolved it.

King Abdullah I of Jordan sent his army, the Arab Legion, into the West Bank. Jordan then annexed (officially took control of) the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. Jordan gave citizenship to the Arabs living there. Many Arab leaders were against this, as they still hoped for an independent Arab state of Palestine. Jordan even changed its name from Transjordan to Jordan in 1949.

After the war, the 1949 Armistice Agreements set the lines between the fighting sides. Israel controlled some areas that were meant for the Arab state under the UN plan. Jordan controlled the West Bank, and Egypt controlled the Gaza Strip.

Jordanian Control of the West Bank

King Abdullah I of Jordan annexed the West Bank, giving citizenship to its Arab residents. This was against the wishes of many Arab leaders who still wanted a separate Arab state. Abdullah also issued a decree forbidding the use of the term "Palestine" in legal documents.

In December 1948, a meeting called the Second Arab-Palestinian Congress was held in Jericho. The delegates declared Abdullah King of Palestine and called for the West Bank to unite with Jordan. The Jordanian government agreed to this union. In April 1950, a joint Jordanian National Assembly officially approved the union.

Only Britain and Pakistan formally recognized Jordan's annexation of the West Bank. However, many other countries, including the United States, treated it as a reality.

The Six-Day War (1967)

In June 1967, Israel captured and occupied the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) from Jordan. It also took the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, and the Golan Heights from Syria. This happened during the Six-Day War.

The international community generally considers the West Bank and Gaza Strip to be under military occupation by Israel. Even after Israel withdrew from Gaza in 2005, the UN and many others still consider it occupied.

After the war, the U.S. stressed to Israel that any peace agreement would need to give Jordan a special role in Jerusalem. The U.S. also expected Jordan to get most of the West Bank back.

In 1970, after fighting broke out in Jordan between the Jordanian army and Palestinian groups, the U.S. government started thinking about creating a separate Palestinian state. However, they doubted if such a state would be strong enough on its own.

The PLO and the Idea of One State

Before the Six-Day War, the movement for an independent Palestine grew stronger. In 1964, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was formed. Its goal was to create a Palestinian state across all the land of the former British Mandate. This goal meant that Israel would not exist. The PLO became the main force in the Palestinian national movement, and Yassir Arafat became its leader.

In 1969, the Fatah movement, a part of the PLO, said it was not fighting against Jewish people, but against Israel as a political entity. The PLO then stated its goal was to create a "free and democratic society in Palestine for all Palestinians, whether they are Muslims, Christians or Jews." This was an idea for a "binational state" where everyone would live together. However, the PLO couldn't get enough support for this idea from Israelis.

Growing Apart: Jordan and Palestinian Leadership (1970)

After a conflict in Jordan in September 1970, the relationship between the Palestinian leadership and Jordan worsened. The Arab League stated that the Palestinian people had the right to decide their own future. They also said the PLO was the "sole legitimate representative" of the Palestinian people.

King Hussein of Jordan then gave up Jordan's claims to the West Bank. He allowed the PLO to take on the role of a temporary government for Palestine.

The Ten Point Program (1974)

In 1974, the PLO adopted the Ten Point Program. This plan still called for a single democratic state for Israelis and Palestinians. But it also said the PLO would work to establish Palestinian rule on "any part" of its liberated territory. This was seen by some as a step towards accepting a two-state solution. This idea caused a split within the PLO, as some hardline groups disagreed.

At a meeting in Rabat in 1974, Jordan and other Arab League members officially declared the PLO as the "sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people." This meant Jordan gave up its role as the representative of the West Bank.

In 1978, during peace talks between Israel and Egypt, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat suggested creating a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza. Israel refused this idea.

In 1982, U.S. President Ronald Reagan called for a freeze on Israeli settlements and supported Palestinian self-rule in a political union with Jordan.

In 1988, King Hussein of Jordan again dissolved the Jordanian parliament and gave up Jordan's claims to the West Bank. The PLO then took on the role of the Provisional Government of Palestine, and an independent state was declared.

Declaration of the State of Palestine (1988)

The declaration of a State of Palestine happened in Algiers on November 15, 1988. It was made by the Palestinian National Council, which is the main body of the PLO. The declaration was approved by a large majority. After reading it, Yasser Arafat, the PLO Chairman, took the title of "President of Palestine."

The declaration did not specify the exact borders of the state. Jordan recognized the new state and gave up its claim to the West Bank to the PLO.

The declaration talked about the "historical injustice" to the Palestinian people. It referred to past agreements and UN resolutions that supported Palestinian rights. It then declared a "State of Palestine on our Palestinian territory with its capital Jerusalem." The declaration said the State of Palestine is for Palestinians everywhere and is an Arab state.

Along with the declaration, the PLO called for talks based on United Nations Security Council Resolution 242. This was a big step, as it suggested the PLO was accepting a "two-state solution," meaning it no longer questioned Israel's right to exist.

As a result of this declaration, the United Nations General Assembly invited Arafat to speak. The UN General Assembly then passed a resolution "acknowledging the proclamation of the State of Palestine." It also decided that "Palestine" should be used instead of "Palestine Liberation Organization" in the UN system. Palestine's representative was given a seat in the UN General Assembly. Many countries around the world recognized Palestine after this.

Palestinian Authority (1994)

In the 1990s, important steps were taken to try and solve the conflict through a two-state solution. This started with the Madrid Conference of 1991 and led to the 1993 Oslo Accords between Palestinians and Israelis. These agreements set up a framework for Palestinian self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza.

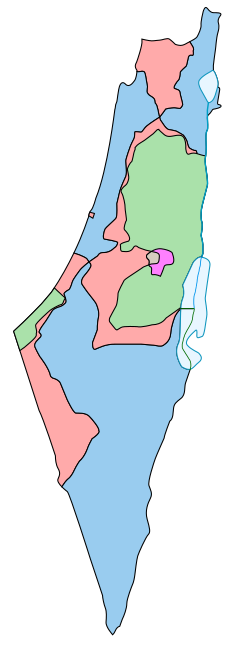

Under the Oslo Accords, Israel agreed to withdraw from the Gaza Strip and some West Bank towns. The Palestinian National Authority (PNA) was then created to govern these areas. The PNA was given limited self-rule over non-connected areas, but it did govern most Palestinian population centers.

In 2005, Israel withdrew completely from the Gaza Strip as part of its Disengagement Plan. This meant the PNA gained full control of Gaza, except for its borders, airspace, and sea.

The international community still considers the West Bank and Gaza Strip to be Occupied Palestinian Territory. This is despite the 1988 declaration of independence and the limited self-government given to the Palestinian Authority.

Split of Fatah and Hamas

In 2007, after Hamas won legislative elections, a violent conflict broke out between Hamas and Fatah (another Palestinian political group). This mainly happened in the Gaza Strip. Hamas took control of Gaza, and Palestinian Authority Chairman Mahmoud Abbas (from Fatah) dismissed the Hamas-led government. He appointed a new Prime Minister, but this government's authority was limited to the West Bank. Hamas continued to rule the Gaza Strip.

Palestine in the United Nations

2011 UN Membership Application

After a long pause in talks with Israel, the Palestinian Authority tried to gain full recognition as a state at the UN General Assembly in September 2011. They wanted recognition based on the 1967 borders, with East Jerusalem as their capital. For this to happen, they needed approval from the UN Security Council and a two-thirds majority in the UN General Assembly.

The United States warned that if the Palestinians went ahead with this, it could affect U.S. financial support for the UN. Palestinian leaders then suggested they might ask for a less formal "non-member state" status, which only needed approval from the UN General Assembly.

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas said he would return to negotiations if Israel agreed to the 1967 borders and the right of return for Palestinian refugees. Israel called the plan a "unilateral step." The Arab League formally supported the Palestinian plan.

On September 23, Abbas officially submitted the application for UN recognition and full membership for a Palestinian state. However, on November 11, the Security Council said it could not make a "unanimous recommendation" on membership.

Non-member Observer State Status in the UN (2012)

Since their application for full membership was stuck, Palestinian representatives decided to seek an upgrade in status from "observer entity" to "non-member observer state." This change only required a vote in the UN General Assembly.

On November 29, 2012, the UN General Assembly voted 138 to 9 (with 41 abstentions) to adopt Resolution 67/19. This resolution upgraded Palestine to "non-member observer state" status in the United Nations. This new status is similar to that of the Holy See (Vatican City). Many saw this as a de facto (in practice) recognition of the sovereign state of Palestine.

This vote was a historic moment for the recognition of the State of Palestine. It was seen as a diplomatic setback for Israel and the United States. Being an observer state allows Palestine to participate in UN General Assembly debates and join international treaties and UN agencies. This could allow Palestine to join bodies like the International Criminal Court (ICC). In 2014, it was confirmed that this new status qualified Palestine to join the ICC. On December 31, 2014, President Abbas signed a declaration recognizing the ICC's authority over crimes committed in Palestinian territory since June 2014.

The UN can now also help confirm the borders of the Palestinian territories that Israel occupied in 1967. Palestine could also claim legal rights over its waters and airspace as a recognized sovereign state.

After the resolution passed, the UN allowed Palestine to call its office at the UN "The Permanent Observer Mission of the State of Palestine to the United Nations." This showed the UN's de facto recognition of Palestine's sovereignty. Palestine also began to use "State of Palestine" on official documents and passports. In January 2013, President Abbas officially changed all designations of the "Palestinian Authority" to the "State of Palestine."

2013 State of Palestine Decree

Following the successful UN status upgrade in 2012, President Abbas signed a decree on January 3, 2013. This decree officially changed the name of the "Palestinian Authority" to the "State of Palestine." It stated that all official documents, seals, and letterheads would now use the name "State of Palestine."

On January 5, 2013, Abbas ordered all Palestinian embassies to change official references to the Palestinian Authority to "State of Palestine." However, due to negative reactions from Israel, it was later announced that the change would not apply to documents used at Israeli checkpoints unless Abbas made a further decision.

Turkey became the first state to recognize this change. In April 2013, the Turkish Consul-General in East Jerusalem presented his credentials as the first Turkish Ambassador to the State of Palestine.

Peace Process Efforts

Oslo Accords

The Oslo Accords were a series of important agreements signed in the 1990s between Palestinians and Israelis. These agreements aimed to solve the conflict through a two-state solution. They set up a framework for Palestinian self-rule in the West Bank and Gaza.

Under the Oslo Accords, Israel agreed to withdraw from the Gaza Strip and some cities in the West Bank. The Palestinian National Authority (PNA) was then created to govern these areas. The PNA was given limited self-rule over non-connected areas, though it governs most Palestinian population centers.

The peace process faced difficulties, especially after the collapse of the Camp David 2000 Summit between Palestinians and Israel and the start of the second Intifada (a Palestinian uprising).

In 2002, the United States proposed a "Road Map for Peace." This plan aimed to end the violence and create an independent Palestinian state. However, the plan stalled because Israel continued to expand settlements and due to conflict between Hamas and Fatah.

In 2005, Israel unilaterally withdrew from the Gaza Strip.

Direct Talks in 2010

In September 2010, direct peace talks were held between Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas. However, the talks stalled when Netanyahu did not extend a temporary halt on building Israeli settlements in the West Bank. Abbas stated that Netanyahu could not be a "true" peace negotiator if the freeze was not extended.

Different Positions

The current position of the Palestinian Authority is that the future "State of Palestine" should be based on all of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Israeli governments have said that the exact borders are subject to future negotiations. The Hamas group, however, believes that all of Palestine (including Israel) should be an Islamic state.

Since 1993, the main discussion has been about creating an independent Palestinian state in most or all of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. This is the basis for the Oslo Accords and is supported by the U.S.

Some Israelis believe that a Palestinian state should not have all the powers of a full state, at least at first. They worry that a fully independent state could become a dangerous enemy. So, they suggest a self-governing entity with limited control over its borders and citizens.

Palestinians, on the other hand, feel they have already made a big compromise by accepting a state only in the West Bank and Gaza. These areas are much smaller than what was originally suggested for an Arab state in the 1947 UN plan. They believe that any further restrictions on their state would make it impossible to have a truly viable (successful) state. They are also upset by the continued growth of Israeli settlements in the West Bank and Gaza. Palestinians feel they have waited long enough and want a state that is not divided.

Countries Recognizing Palestine

Many countries around the world have recognized the State of Palestine. These include most Arab League nations, many African nations, and several Asian nations like China and India.

Other countries, including many in Europe, the United States, and Israel, recognize the Palestinian Authority (PNA) as an autonomous (self-governing) entity. However, they do not formally recognize the 1988 proclaimed State of Palestine.

Some international sports organizations also recognize Palestine as a separate entity. For example, the International Olympic Committee has recognized a separate Palestine Olympic Committee since 1996. FIFA, the world governing body for football, has recognized the Palestine national football team since 1998.

In late 2010 and early 2011, several South American countries like Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Bolivia, and Paraguay recognized a Palestinian state. Russia also reiterated its support and recognition in January 2011.

Images for kids

-

Administrative units in the Levant under the Ottoman Empire, until c. 1918

See also

- Isratin

- Camp David Accords

- Oslo Accords

- Arab–Israeli conflict

- British Mandate for Palestine

- 2000 Camp David Summit

- King Hussein's federation plan

- Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel, May 14, 1948

- Foreign relations of the Palestine Liberation Organization

- Geneva Accord

- Arab Peace Initiative

- Israeli–Palestinian conflict

- Palestine Investment Conference

- Proposals for a Jewish state

- Right to Exist

- Occupation of the Gaza Strip by Egypt

- Jordanian annexation of the West Bank

- One-state solution

- Two-state solution

- Palestinian National Authority

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |