History of wood carving facts for kids

Wood carving is one of the oldest art forms made by people. Humans have used wood for tools and art for thousands of years. For example, ancient wooden spears from the Middle Paleolithic era show how early humans worked with wood. However, wood can decay quickly, so not many very old wooden objects have survived.

Many cultures around the world have used wood carving. North American Indians carved everyday items like fishhooks and pipe stems. Polynesian people carved paddles and tools. Natives in Guyana decorated their cassava graters, and people from Loango Bay carved spoons with detailed figures. Wood carving was also a big part of their buildings.

Carving faces in wood can be tricky because of the wood's texture. But sometimes, the rough grain of the wood can actually help create realistic features, like wrinkles on an older face. In ancient times, carvings were often painted. This protected the wood and added color, making the artwork even more beautiful and detailed.

In the early 1900s, wood carving became less popular. It was slow and needed a lot of skill, making it expensive. Cheaper ways to decorate things became common. Machines also started doing some of the work. However, wood carving is still a living art form today, with many talented woodcarvers around the world.

Contents

Ancient Wood Carving

The dry climate of Egypt helped many ancient wood carvings survive. Some wood panels from a tomb at Sakkarah, from the Old Kingdom (around 2686–2181 BC), show delicate carvings of Egyptian hieroglyphs and figures. A stool on one panel has legs shaped like animal limbs, a design used in Egypt for thousands of years.

The Cairo museum has a famous wooden statue of a man from around 4000 BC. Its face and posture are incredibly realistic. The statue is carved from a single block of sycamore wood, with arms added separately. The eyes are made with white quartz and rock crystal, giving them a lifelike sparkle. Egyptian sculptors from the Old Kingdom were masters at creating detailed portraits. These statues were important for religious reasons, believed to be homes for the spirits of the dead.

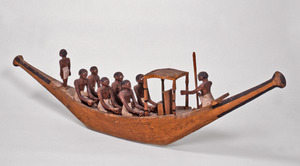

Many Egyptian wood carvings can be found in museums. These include mummy cases, sometimes with only the face carved, or animal-shaped boxes. Furniture like folding stools and chairs with animal-shaped legs also exist. Headrests, similar to those used in New Guinea today, were carved with scenes. Tiny boxes, incense ladles, mirror handles, and perfume boxes shaped like fish were also made. These examples show how advanced wood carving was thousands of years before Christ.

We know less about wood carving from Assyria, Greece, and Rome. However, it's likely that their wood carving was as skilled as their other arts. Important wooden Roman sculptures are known from old descriptions. Many ancient wooden statues of gods were kept for a long time. The Palladium, a sacred wooden figure of Pallas in Rome, is one famous example.

European Wood Carving

Great wooden artworks were made in Europe during the Middle Ages, especially in Cathedrals, abbeys, and churches. These pieces show amazing skill and artistry.

Early Centuries (1st-11th CE)

Wood carvings from the first eleven centuries CE are rare because wood decays easily. The carved panels of the main doors of St Sabina in Rome are important examples of early Christian wood carving from the 5th century. Each small panel is intricately carved with scenes from the Bible.

A beautiful piece of Byzantine art from the 11th or 12th century is at Mount Athos in Macedonia. It has two carved panels with detailed patterns of leaves and animals. In Scandinavian countries, some very old and well-designed wooden pieces exist, both Christian and non-Christian. Examples include chairs in the Christiania Museum and panels from Iceland. Famous wooden doorways from Norwegian churches (around 1200 CE) feature dragons and complex scrollwork.

Gothic Period (12th–15th Centuries)

Wood carving reached its peak during the Gothic period. The choir stalls, rood-screens, roofs, and altarpieces in England, France, and Germany were incredibly detailed and well-proportioned. While later carvers might have matched the detail, the overall design and decorative style of the 15th century were unmatched.

Color was very important in Gothic carving. Most carvings were painted to protect them and to make them look splendid. Red, blue, green, white, and gold were common colors. Screens were often painted, and plain surfaces were decorated with delicate patterns of leaves or saints. The altarpieces from Germany, Flanders, and France were stunning, showing scenes from the New Testament in high relief, surrounded by delicate carvings and bright colors.

Gothic design often involved craftsmen working directly on site. Carvers would travel from church to church, and you can see their unique styles in different areas. While one main artist planned the overall design, individual workers had freedom with details. This led to endless variety and charm in Gothic art. Carvers often worked right in the church, sometimes leaving pieces unfinished.

Gothic Design Styles

Gothic design usually falls into two types:

- Geometrical patterns: Like tracery (patterns made of intersecting lines) and diaper patterns (repeating diamond shapes).

- Foliage designs: Where leaf patterns were used, often without the mechanical scrolls seen later.

Unlike Renaissance designers who often made both sides of a panel identical, Gothic carvers rarely repeated every detail. Their main lines might match, but the small details would be different.

13th Century Carving

The 13th century showed great skill and deep religious feeling in carving. Work was delicate and beautifully cut. Examples of carved capitals can be seen in Peterborough Cathedral. Exeter Cathedral has amazing misericords (small seats in choir stalls) carved with mermaids, dragons, and knights. Salisbury cathedral is known for its stall elbows.

14th Century Carving

From 1300 to 1380, leaf shapes in carvings became more natural, though still stylized. The choir of Winchester has beautiful carvings of oak and other leaves. The choir stalls of Ely and Chichester are also fine examples. Exeter has a throne for Bishop Stapledon (1308–1326) that is 57 feet tall, known for its perfect proportions and delicate details.

15th Century Carving

Towards the end of the 14th century, carvers started using more conventional, less natural leaf forms. The vine plant was very popular. A lot of 15th-century work still exists today.

The rood screen was a common feature in churches. It was a tall screen, about 30 feet high, with a platform called a "loft" on top. The loft had a gallery, and a large crucifix (the "rood") with figures of Mary and John was placed on or in front of it. The lower part of the screen was solid, often painted with saints. The upper part had open arches with carved tracery. The loft floor often rested on a carved vaulting. The finest examples of this vaulting are in Devon, England. The edges of the loft floor were often decorated with detailed foliage, especially vine leaves.

England has some of the best 15th-century church roofs. The great roof of Westminster Hall is unique. Many churches in Norfolk and Suffolk have hammerbeam roofs, like the one at Woolpit, Suffolk, which has carved brackets, angels on beams, and crested purlins. The idea of angels in the roof was very beautiful, especially when colored.

Choir stalls became even more magnificent in the 15th century. Manchester Cathedral and Henry VII's chapel in Westminster Abbey show how carvers started adding many pinnacles and canopies. The stalls in Amiens were considered among the finest in the world. The choir stalls in Ulm Minster, made by Jörg Syrlin the Elder, are also excellent examples of German carving, with bold foliage and sculptures.

Benches for the nave (the main part of the church) became common in the 15th century. The "poppyhead" design, a carved finial at the top of the bench end, became very popular in England. These could be simple fleur-de-lys shapes or elaborate designs with figures, birds, or faces. The sides of the bench ends were often decorated with tracery or scenes.

Pulpits became more common in the 15th century as preaching grew in importance. A beautiful octagonal pulpit exists at Kenton, Devon, with carved columns and panels painted with saints. The pulpit at Trull, Somerset, is known for its fine figures. Font covers were often pyramidal, sometimes with a small angel on top. The most beautiful ones were covered in pinnacles and canopy work, like the one at Sudbury, Suffolk.

Many lecterns (reading stands) from the Gothic period had a double sloping desk that rotated. Doors were often carved, especially in the Tudor period in England, with linenfold paneling (carving that looks like folded linen).

The altar-piece was a very important church decoration, especially in Spain and Germany. The magnificent altarpiece in Schleswig Cathedral, carved by Hans Bruggerman, features many figures in deep relief, creating a sense of depth. These figures show a wide range of expressions and movement.

Paneling in the late Gothic period had three main styles:

- Developed tracery: Square panels filled with detailed, flowing patterns.

- Linenfold design: Carvings that look like folded fabric, used for large surfaces.

- Flat hollow mouldings: Designs with simple, often interlacing, lines and small decorative elements.

Few domestic wood carvings from this period remain. However, examples in places like Rouen show how religious themes were part of everyday life. Carved corner posts supporting overhanging stories were common in England, like those in Ipswich. Mantelpieces and cabinets were also carved. Chests were very important pieces of furniture, often covered with elaborate carvings, like a hunting scene on a chest in the Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin.

It's hard to compare English figure carving with that on the Continent due to the Reformation, which led to the destruction of many religious images. However, the roofs, bench ends, and misericords in England show how much wood sculpture was used. While not always of the highest artistic quality, some pieces, like the stall elbows of Sherborne, are exceptional.

Renaissance Period (16th–17th Centuries)

The Renaissance style gradually replaced Gothic design starting in the 16th century. This new style was different, focusing more on classical elements. The best work from this period is found in France, Germany, and the Netherlands. As trade grew, so did the desire for more refined decoration.

Pilasters (flat, decorative columns) replaced pinnacles, and classical motifs like vases, dolphins, and acanthus leaves became popular. Wooden house fronts offered great opportunities for carvers. Sir Paul Pinder's house (1600), now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, shows decorative carving without being too busy.

In England, the Elizabethan and Jacobean styles were popular. Many homes still have old oak chests with carved half-circles or arch patterns. Court cupboards with thick, turned legs were common. Chairs with solid, carved backs were also popular. Four-post bedsteads often had carved panels. Dining tables had thick, turned legs. Rooms were often paneled with oak.

The fire mantle was a key feature in Elizabethan rooms. Carvers often extended the chimney breast to the ceiling, covering it with elaborate carvings like caryatid figures (carved female figures used as columns), pilasters, and friezes (decorative bands). The mantelpiece from Bromley-by-Bow, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, is a beautiful example. Elizabethan carvers also made splendid staircases, sometimes carving the newel posts with heraldic figures.

French wood carving in this period also used flat, simple designs. Doors were often decorated this way, and the split baluster (a half-round column shape) common in Jacobean work was also seen. Swiss and Austrian carvers added color to this style. However, the best European designs adopted the classical acanthus leaf from Italy, while still keeping some of the strength of Gothic lines.

Cabinets from the Netherlands and Belgium are excellent examples of design. They often had two levels with fine carved cornices and pilasters. Some French cabinets were overloaded with sculpture. The doors of St Maclou, Rouen, are very fine, though perhaps too ornate by today's standards.

Italy, the birthplace of the Renaissance, produced much fine 16th-century work. Artists like Raphael influenced many carvers. The shutters in Raphael's Stanze in the Vatican and the choir stalls in Perugia are beautiful examples of this style. The carvings are in slight relief, using graceful patterns inspired by ancient Roman wall paintings. The Victoria and Albert Museum has many Italian pieces, including a door with masks, a picture frame with an acanthus border, and elaborate marriage chests.

17th–18th Centuries

In England, the famous carver Grinling Gibbons emerged. He created beautiful, highly detailed carvings that looked like they were copied directly from nature. He carved thick pieces of lime wood into swags of drapery, fruit, flowers, and dead birds. These carvings were incredibly skillful, with each grape undercut and delicate stalks standing out. Examples can be seen at Hampton Court Palace, Chatsworth, and St Paul's Cathedral.

During the reigns of Louis XIV and XV in France, the purpose of carving sometimes got lost. Furniture was often carved in ways that ignored its practical use. Legs of tables and chairs, and cabinet frames, were designed to hold cherubs or rococo (rock and shell) ornaments, rather than for strength. This style was also used on carriages and beds. However, wall paneling in wealthy homes was often decorated with rococo designs, with plain surfaces and a carved medallion in the center. France led this fashion across Europe.

English cabinet-makers like Thomas Chippendale used less carving, but still added fine relief scrolls, shells, and ribbons to chairs. The "claw and ball" foot was a popular design for furniture legs. Mantelpieces in the 18th century were usually carved in pine and painted white, with shelves supported by pilasters or caryatids, and a carved frieze.

Interior doorways often had decorative broken pediments. Outside porches on Queen Anne houses had heavy, carved brackets. Staircases were usually very well made, with carved and pierced brackets supporting graceful balustrades.

Renaissance figure carving was good in the 16th century, but later, figures used on cabinets were often not as impressive. In the 18th century, cherub heads were popular, and small statues were carved as ornaments. However, wood sculpture became less common for decorating houses. The Swiss, though, continued to be known for their animal sculptures, like chamois and bears.

Between the 17th and 18th centuries, a thriving wood carving industry began in the Gardena valley in Italian South Tyrol. Carvers from this valley traveled across Europe to sell their products. In the 19th century, millions of wooden toys and dolls were carved there. The Museum Gherdëina in Urtijëi has a large collection of these carvings.

Gilded woodcarving in Portugal and Spain continued to be produced, and this style was exported to their colonies in the New World, the Philippines, Macao, and Goa.

Wood Carving in Other Cultures

Coptic Carving

In the early medieval period, Christian carvers in Egypt made screens and fittings for Coptic churches. The British Museum has cedar panels from a 13th-century church door in Cairo. Some panels have figures in low relief, while others have intricate, fine foliage patterns, showing an Oriental style.

Islamic Carving

Muslim wood carvers from Persia, Syria, Egypt, and Spain were famous for their skill. They created rich paneling and decorations for walls, ceilings, pulpits, and furniture. Mosques and homes in cities like Cairo and Damascus are filled with detailed woodwork. A popular style involved intricate patterns made from finely shaped ribs, with the spaces filled with small pieces of wood carved with delicate foliage. Different woods, like ebony or boxwood, were often inlaid to highlight the design. Carved ivory was also used.

Screens made of complex patterns of tiny balusters connecting hexagons or squares are common in Islamic art. These flat surfaces were often enriched with small carvings. The Arabs were masters at carving flat surfaces this way. A gate in the mosque of Sultan Bargoug in Cairo (14th century) shows their skill with lines and surfaces.

Persian Carving

Persian carvers followed Arab designs closely. A pair of 14th-century doors from Samarkand in the Victoria and Albert Museum are typical. Small items like boxes and spoons were often decorated with intricate patterns, requiring great patience and skill. Sometimes, a beautiful effect was created by using a small amount of open lattice patterns among foliage.

Indian and Burmese Carving

India has produced luxurious wood carving for centuries. Ancient Hindu temples had doors, ceilings, and fittings carved from teak and other woods with incredibly rich and detailed patterns. Many doors, columns, and even entire house-fronts are covered in complex designs. However, Indian carvers could also be more restrained, adding carvings around architectural frames. Hindu designs often used circles very well. Foliage, fruit, and flowers were adapted for fret-cut decorations on doors, windows, and furniture. Southern Indian carvers often worked with sandalwood, covering it with scenes from Hindu mythology. Gong stands from Burma often show high skill, with figures holding a pole from which a gong hangs.

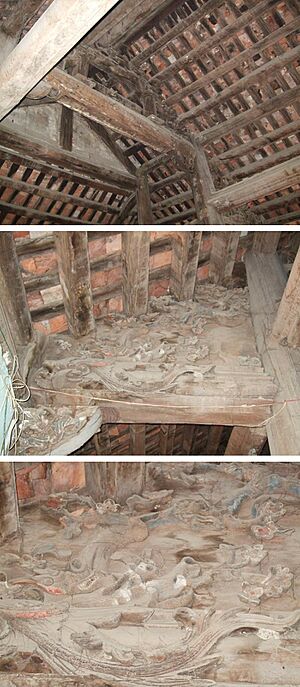

Indochina and Far East Carving

Carvers in these countries, especially Japan, are known for their incredible skill. They create very detailed and realistic carvings, particularly when copying plants like the lotus. A common decoration style involves dividing surfaces like ceilings and columns into framed squares, filling each with a circle or diamond pattern. A unique Chinese feature is the finial (top ornament) of the newel post, often carved with monsters and scrolls. Heavy, rich moldings and dragons arranged in natural curves are also common.

Chinese design often uses similar patterns to those found in Gothic Europe. Screens with grill-like patterns are common, similar to those in Islamic countries. The imperial dais in the Chien-Ching Hall in Beijing is a masterpiece of intricate design, with luxuriously carved panels and a heavy crest of dragons.

In Japan, many Chinese influences are seen. Japanese carvers often mass foliage without a clear stalk, placing leaves, fruit, and flowers first and then adding stalks. This creates a highly decorative effect, especially when birds and animals are included. Japanese figure carving is as strong and detailed as the best Gothic sculpture from the 15th century.

Other Carving Styles

The Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica describes chip carving (removing small chips from wood with knives or chisels) and designs made with incised lines as being found all over the world. Relief carving is also common globally.

The Encyclopædia mentions the unique carving style of the Cook Islands, which uses small triangles and squares to cover surfaces. Fijian chip designs are said to rival European ones in variety. Carvers from the Marquesas Islands understood how plain surfaces could make decorated parts stand out, focusing their work on bands or specific points. Māori carving uses scrollwork and carvings, especially for houses. Art from New Guinea also features scrollwork, similar to guilloché patterns and Scandinavian work.

The Ijaw people of Nigeria are noted for their masterful paddle designs, showing a good balance between plain and decorated areas. Their designs are slightly in relief and have a chip-carved look. In art by Indigenous Americans, twisted shapes are a favorite way to decorate pipe stems.

Modern Wood Carving

In the 19th century and beyond, there has been less demand for carved decoration, except for collecting old pieces. Some carvers still work on church projects, repairs, or making imitations. However, much of the carving seen in hotels or on modern ships is done by machines, with human workers often adding finishing touches.

Despite this, the teaching of wood carving became more formalized in Europe in the 1800s. For example, the Austrian woodcarver Josef Moriggl (1841–1908) had a long career teaching the craft. In the Gröden valley, an art school opened in 1820, greatly improving carvers' skills. This led to a new industry where artists and artisans created sculptures and altars that were exported worldwide. Unfortunately, machine carving, which started in the 1950s, caused many carvers in Val Gardena to stop their craft.