Native American art facts for kids

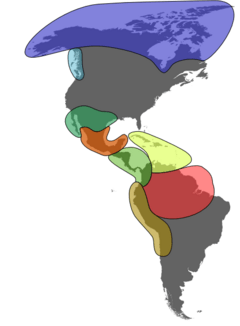

Native American art includes all the amazing visual art made by Indigenous peoples from South America and North America. This includes Central America and Greenland. This art spans from ancient times all the way to today.

Sometimes, their art was portable. This means it could be carried around. Examples include paintings, baskets, textiles (woven cloth), and photography. Other times, Native Americans created art that stayed in one place. This included architecture (buildings), land art, large sculptures, or murals (wall paintings).

Europeans started collecting Indigenous art when they first sailed to the Americas in 1492. Today, Native scholars are working to understand Indigenous art in the right way.

Contents

Ancient Art: Stone Age to Early Cultures

Early Stone Age Art (Lithic and Archaic Periods)

The Lithic stage, or Paleo-Indian period, was from about 16000 to 8000 BC. The oldest known art in the Americas is a fossilized megafauna bone. It might be from a mammoth and has a carving of a mammoth or mastedon on it. Scientists think this carving, found in Vero Beach, Florida, is from 11000 BC.

The oldest known painted object in North America is the Cooper Bison Skull. It is from about 8050 BC. In South America, rock paintings from the Monte Alegre culture were found in Caverna da Pedra Pintada. These date back to 9250 to 8550 BC. The earliest known textiles, found in Guitarrero Cave in Peru, are from 8000 BC.

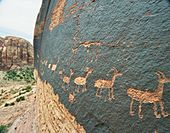

The Archaic stage came after the Lithic stage. It lasted from about 8000 BC to 1000 BC. People during this time used many different materials for their art. Some of their art, like bannerstones, Projectile points, and pictographic cave paintings, still exist. The southwestern United States and parts of the Andes have the most pictographs (painted images) and petroglyphs (carved images) from this time. Both are known as rock art.

-

A petroglyph of bighorn sheep near Moab, Utah. This was a common theme in desert carvings.

-

Ancient abstract petroglyphs from the Coso Rock Art District, California. -

Petroglyph from Columbia River Gorge, Washington.

Art by Region

Arctic Art

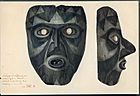

The Yup'ik people of Alaska have a long history of carving masks. They used these masks in shamanic rituals.

Indigenous peoples in the Canadian arctic have made art since the Dorset culture period. The Thule people, who came after them around AD 1000, used walrus ivory for more than just rituals. They also used it for decoration. This tradition continues today. Many Inuit artists still create art for tourists and whaling ship crews. Their art includes cribbage boards, serpentine sculptures, textiles, beadwork collars, and masks. Sperm whale ivory is still an important material for carving.

- Inuit art from Alaska, Canada, and Greenland

-

Toy Angakkuq (shaman) by Palaya Qiatsuq. Made of serpentine, caribou bone, and feathers.

Subarctic Art

People living in the middle part of Alaska and Canada, south of the Arctic Circle, are called Subarctic peoples. Their oldest known art is a petroglyph site in northwest Ontario, from 5000 BC. Caribou and moose are very important to Subarctic people. They provide hides (skins), antlers, sinew, and other materials for art. Porcupine quillwork decorates hides and birchbark. Moose hair tufting and glass beadwork with flower designs also became popular.

-

21st-century Athabaskan moosehair tufting on a beaded hide box, Fairbanks, Alaska.

-

Tsuu T'ina painted hide tipi, Alberta, Canada.

Northwest Coast Art

Woodworking was a very popular art form for the Haida, Tlingit, Heiltsuk, Tsimshian, and other tribes. These groups lived along the coast of Washington state, Oregon, and British Columbia. Famous examples of their woodwork include totem poles, transformation masks, and canoes.

Jewelry made from engraved silver, gold, and copper became important after Europeans settled in the Americas.

-

A totem pole in Ketchikan, Alaska, in the Tlingit style.

-

Namgis thunderbird transformation mask from the 19th century.

-

Haida argillite carving from 1850–1900, from Haida Gwaii.

-

Cedar bark hat by the Nuu-chah-nulth people.

Eastern Woodlands Art

Northeastern Woodlands Art

The Eastern Woodlands cultures lived in North America, east of the Mississippi River, since at least 2500 BC. Many tribes lived here and traded with each other. They are sometimes called Mound builders because they buried their dead in earth mounds. This helped preserve much of their art.

The Woodland period (1000 BC - AD 1000) had three parts. Cultures during this time mostly hunted and gathered food.

- The Early Woodland period (1000 BC - 200 BC) was a time of development. The Deptford culture and Adena culture carved stone tablets with animal designs. They also made ceramics, pottery, and costumes. Engraved shells have been found in their burial mounds.

- During the Middle Woodland period (200 BC - AD 500), the Hopewell tradition grew strong. Their artwork included many types of jewelry and sculptures made from stone, wood, and even human bone.

- During the Late Woodland period (AD 500 - 1000), settlements traded less and became smaller. This led to less art being created.

From the 12th century onward, the Haudenosaunee (pronounced EER-i-coy) and nearby coastal tribes made wampum from shells and string. These wampum were used to help remember things, as currency (money), and to record treaties.

Much of the art from this period has been saved or copied. Examples include False Face masks and Corn Husk Society masks of the Iroquois people. Artists like Edmonia Lewis and Sharol Graves also created important works.

- Art from the Eastern woodlands of North America

-

Hopewell mounds from the Mound City Group in Ohio. -

Carved soapstone pipe showing a raven, Hopewell tradition. -

Copper falcon from the Mound City Group site. -

Great Treaty wampum belt given from the Lenape to William Penn, Pennsylvania, 1682.

Southeastern Woodlands Art

The Poverty Point culture lived in parts of Louisiana from 2000 to 1000 BC during the Archaic period. Their art used materials from places as far away as the Ohio and Tennessee River valleys, Alabama, and Georgia. These materials included chipped stone, ground stone, shell and stone beads, soapstone, and clay.

-

Carved gorgets and atlatl weights, Poverty Point.

The Mississippian culture thrived in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from about AD 800 to 1500. This culture started to rely on maize (corn) as their main food. This meant they did not need to hunt as much. They built platform mounds that were larger and more complex than those of earlier groups. They also developed better ways to make ceramic pottery. They used ground mussel shell as a tempering agent (a material added to clay to stop it from cracking). Tribes that came from Mississippian cultures include the Natchez, Taensa, Caddo, Choctaw, Muscogee Creek, and Wichita.

-

Engraved shell gorget, Spiro Mounds (Mississippian culture). -

Engraved stone palette, Moundville Site, used for mixing paint (Mississippian culture). -

Stone figures, Etowah Site (Mississippian culture). -

Ceramic underwater panther jug, Rose Mound (Mississippian culture).

Many wooden art pieces have been found in Florida. The most famous is a 30-inch-tall carving of an eagle. More than 1,000 carved and painted wooden objects, including masks and statues, were found at an archaeological site in 1896 at Key Marco, in southwestern Florida.

The Seminoles are best known for their textile art, especially patchwork clothing. Doll-making is another important craft.

-

Seminole patchwork fringed dance shawl, Big Cypress Indian Reservation, Florida, 1980s.

Art of the West

Great Plains Art

Tribes have lived on the Great Plains for thousands of years. Early Plains cultures are divided into four periods. The oldest known painted object in North America, the Cooper Bison Skull, was found in Oklahoma. It is from 10900 - 10200 BC and has a red zig-zag design.

During the Plains Village period, some cultures settled in rectangular houses and grew maize. Tribes were both hunters, who used horses to follow buffalo, and farmers.

Buffalo hide clothing was decorated with porcupine quill embroidery and beads. Later, coins and glass beads from trading were used. Plains tribes used buffalo hide for painting. Men painted their adventures, visions, history, and calendars called winter counts. Women painted designs that were sometimes used as maps.

Later, Plains artists had to use new surfaces for painting, like muslin or paper. This happened in the late 19th century because non-native hunters had killed too many buffalo.

-

Sioux dress with a fully beaded yoke. -

Sioux beaded and painted rawhide parfleches. -

Ledger drawing of Haokah (c. 1880) by Black Hawk (Lakota). -

Kiowa ledger art, possibly of the 1874 Buffalo Wallow battle, Red River War.

Great Basin and Plateau Art

The Plateau region, also known as the Intermontaine and upper Great Basin, was a trade center since ancient times. Plateau people usually lived near major rivers. Because of this, they copied art styles from other regions, like the Pacific Northwest coasts and the Great Plains. Nez Perce, Yakama, Umatilla, and Cayuse women weave flat, rectangular bags from corn husks or hemp dogbane. These bags have "bold, geometric designs." Plateau beadworkers are known for their bead shapes and detailed horse pictures.

Great Basin tribes have a very skilled basket-making tradition. Paiute, Shoshone, and Washoe basketmakers are known for baskets with seed beads on the surface and for waterproof baskets.

-

Nez Perce bag with contour beadwork, c. 1850 - 1860. -

Shoshone beaded men's moccasins, circa 1900, Wyoming. -

Basket by Carrie Bethel (Mono Lake Paiute), California, 30" diameter, c. 1931 - 1935.

California Art

The Native Americans in California are famous for their basket weaving art. In the late 19th century, Californian baskets by artists from the Cahuilla, Chumash, Pomo, Miwok, Hupa, and many other tribes became popular. Because of this, Californian Native American tribes started making more kinds and shapes of baskets.

California has many pictographs and petroglyphs. Some pictographs are very detailed. Big and Little Petroglyph Canyons in the Coso Rock Art District of the northern Mojave Desert in California have the most petroglyphs in North America for their size.

Southwest Art

In the Southwestern United States, many pictographs and petroglyphs were created. People used the Barrier Canyon Style in famous places like Horseshoe Canyon, Newspaper Rock, and Arches National Park.

The Ancestral Puebloans, also called Anasazi, (1000 BC - AD 700) are the ancestors of today's Pueblo tribes. Their culture grew in the American Southwest after they learned to grow corn around 1200 BC. People in this region were farmers. They grew food, gourds for storage, and cotton. Since they did not move around much, they made pottery to store water and grain. Some pottery was for daily use, but they also made more detailed and colorful pottery for rituals. These were often polished and decorated with painted designs.

Around AD 200, the Hohokam culture developed in Arizona. They are the ancestors of the Tohono O'odham and Akimel O'odham (Pima) tribes. The Mimbres, part of the Mogollon culture, are known for painting stories on their pottery.

Southwest architecture includes Cliff dwellings, which are multi-story homes carved into cliffs. There were also pit houses and adobe and sandstone pueblos. One of the largest ancient settlements is Chaco Canyon in New Mexico. It has 15 major complexes of sandstone and timber, connected by roads. Construction for the largest settlement, Pueblo Bonito, began over 1000 years ago. Pueblo Bonito has over 800 rooms.

In the last 1000 years, Athabaskan peoples moved from northern Canada to the Southwest. These include the Navajo and Apache. Sandpainting started as part of Navajo healing ceremonies and became an art form. Navajos learned to weave on upright looms from Pueblos. They wove blankets and later rugs for trade.

Ancestral Pueblo used turquoise, jet, and spiny oyster shells for jewelry. They have used detailed inlay techniques for centuries. In the 1850s, Navajos learned silversmithing from Mexicans. Atsidi Sani (Old Smith) was the first Navajo silversmith. He taught many students, and the skill spread quickly. Today, thousands of artists make silver jewelry with turquoise.

-

Montezuma Castle, a Sinagua cliff dwelling in Arizona, c. AD 700 - 1425.

-

Ancestral Pueblo canteen, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, c. AD 700 - 1100. -

Navajo Sandpainting.

Mesoamerica and Central America Art

The cultural development of ancient Mesoamerica was generally divided into east and west. The long-lasting Mayan culture was strongest in the east, especially on the Yucatán Peninsula. Different civilizations lived in the western area. These included the Teotihuacan (1–500), West Mexican (1000 - 1001), Mixtec (1000–1200), and Aztec (1200–1521).

Central American civilizations generally lived south of modern-day Mexico, though there was some overlap.

Mesoamerican Art

Mesoamerica was home to many cultures, including:

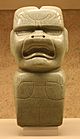

Olmec Art

The Olmec (1500 - 400 BC), who lived on the gulf coast, were the first major civilization to fully develop in Mesoamerica. Their culture was the first to create many features that stayed important until the Aztecs. These included a complex astronomical calendar, the ritual ball game, and building stelae to remember victories.

The most famous Olmec art pieces are colossal basalt heads. Historians think these heads looked like rulers and were made to show their power. The Olmec also sculpted figurines that they buried under their house floors. These were usually made of terracotta, but sometimes carved from jade or serpentine.

-

Monument 1, one of four Olmec colossal heads at La Venta. This one is nearly 9 feet (3 meters) tall.

-

An "elongated man" figurine, dark green serpentine.

Teotihuacan Art

Teotihuacan was a city built in the Valley of Mexico. It has some of the largest pyramids built in the pre-Columbian Americas. The city was founded around 200 BC and fell between the 7th and 8th centuries. Teotihuacan has many well-preserved murals.

-

A mural showing the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan.

-

Mask with a necklace of 55 beads and a pendant. Made of serpentine with amazonite, turquoise, shell, coral, and obsidian.

-

Statue of Chalchiuhtlicue.

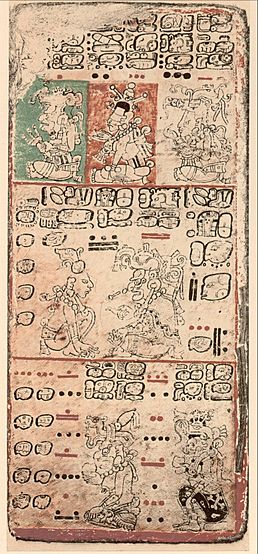

Maya Art

The Maya civilization covered southern Mexico, all of Guatemala and Belize, and western parts of Honduras and El Salvador.

-

Classic Period Maya eccentric flint, possibly from Copán or Quiriguá.

-

Jade plaque of a Maya king; 400 - 800 (Classic period). Found at Teotihuacan.

-

Relief showing Aj Chak Maax presenting captives to ruler Itzamnaaj B'alam III of Yaxchilan; August 22, 783.

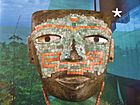

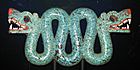

Aztec Art

-

Double-headed serpent; 1450 - 1521; Spanish cedar wood, turquoise, shell.

-

Page 13 of the Codex Borbonicus. This page shows the goddess Tlazōlteōtl giving birth to Centeōtl.

-

Aztec calendar stone; 1502 - 1521; basalt. Discovered in 1790.

Caribbean Art

-

Duho (Ceremonial wooden stool), Hispaniola. Taíno, AD 1000 - 1500. -

Taíno zemi, ironwood with shell inlay, Dominican Republic, 15th - 16th-century. Used for cohoba rituals.

-

Las Caritas, Taíno petroglyphs, Lake Enriquillo, Dominican Republic. -

Taíno batey ball court petroglyph, Caguana, Utuado, Puerto Rico.

South American Art

Native civilizations were most developed in the Andean region. They are generally divided into two groups: Northern Andes (present-day Colombia and Ecuador) and Southern Andes (present-day Peru and Chile).

Hunter-gatherer tribes in the Amazon rainforest of Brazil also have art traditions. These include tattooing and body painting. Because these areas are hard to reach, these tribes and their art have not been studied as much. Many remain uncontacted.

Isthmo-Colombian Area Art

The Isthmo-Colombian Area includes some Central American countries like Costa Rica and Panama. It also includes nearby South American countries like Colombia.

San Agustín Art

-

Animal-human figures from San Agustín Archaeological Park.

-

Figure from San Agustín Archaeological Park.

-

Pendant; AD 1 - 900; gold. From the Gold Museum (Bogotá, Colombia).

Calima Art

Quimbaya Art

Muisca Art

-

The Muisca raft; circa 600–1600; gold alloy.

-

Tunjo; 10th - 16th centuries; from Guatavita Lake region.

Andes Region Art

Chavín Art

-

A Chavin stone sculpture of a head, an ornament from a wall; 9th century BC.

-

Raimondi Stela; 5th-3rd century BCE; granite.

Moche Art

-

Pottery showing a Moche Crawling Feline; ceramic with nacre inlays.

Inca Art

Amazonia Art

Amazonian Indigenous peoples did not have much access to stone and metals. So, they became skilled in featherwork, painting, textiles, jewelry, and ceramics. Feathers are used to create brightly colored headdresses, jewelry, clothing, and fans. Iridescent beetle wings are used in earrings and other jewelry. Weaving and basketry also thrive in the Amazon, like among the Urarina of Peru.

The Island of Marajó, at the mouth of the Amazon River, was a major center for ceramic traditions as early as AD 1000. It still produces ceramics today. These ceramics are usually cream-colored and painted with red, black, and white lines and shapes.

Caverna da Pedra Pintada (Cave of the Painted Rock) in Brazil has the oldest art in the Americas. Its rock paintings date back 11,000 years. The cave also has the oldest ceramics in the Americas, from 5000 BC.

Modern and Contemporary Native American Art

The Start of Modern Native American Art

It's hard for art historians to say exactly when "modern" Native American art began. Native American art history is a new and important area of study. Ancestral Pueblo artists painted with tempera on woven cotton fabric over 800 years ago. Some Native artists used non-Indian art materials as soon as they could get them. For example, Texcocan artist Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxóchitl painted with ink and watercolor on paper in the late 16th century.

In the Native American art world, people often use their art rather than just displaying it. This is called utilitarian art. For example, the Cherokee Nation honors its best artists as Living Treasures. These include makers of frog and fish-gig tools, flint knappers, basket weavers, sculptors, painters, and textile artists.

Non-native people traded for and bought art from Natives since they first met. But from the 1820s to 1840s, the art market became very popular. In the Pacific Northwest and Great Lakes, tribes relied on art for money because the fur trade was slowing down. A painting movement called the Iroquois Realist School began among the Haudenosaunee in New York in the 1820s.

Other modern and contemporary artists include Edmonia Lewis, who sculpted President Ulysses S. Grant. Also, Ho-Chunk artist Angel De Cora and the Kiowa Six are famous. The Santa Fe Indian Market started in 1922 and showed Native American art.

Basketry Today

Basket weaving is one of the oldest and most common art forms in the Americas. Many materials are used to weave baskets. These include sea lyme grass, bark, vegetable fibers, horsehair, baleen (whale bone), copper sheets, wire, and different kinds of grasses.

California and Great Basin tribes are known as some of the best basket weavers in the world. Pomo basket weavers can make 60–100 stitches per inch. Their rounded, coiled baskets are decorated with quail's topknots, feathers, abalone, and clamshell discs. These are known as "treasure baskets."

A complex technique called "double weave" involves weaving both an inside and outside surface at the same time. This is done by the Choctaw, Cherokee, Chitimacha, Tarahumara, and Venezuelan tribes. The Tarahumara, or Raramuri, of Copper Canyon, Mexico, usually weave with pine needles and sotol. In Panama, Embera-Wounaan peoples are famous for their chunga palm baskets with pictures. These are called hösig di and are colored with bright natural dyes.

Yanomamo basket weavers in the Venezuelan Amazon paint their woven trays and burden baskets. They use geometric designs in charcoal and onto, a red berry. While women usually weave baskets in most tribes, among the Waura tribe in Brazil, men weave baskets. They make many styles, but the largest are called mayaku. These can be tightly woven and two feet wide.

Today, basket weaving often leads to environmental activism. Careless pesticide spraying can harm weavers' health. The emerald ash borer attacks the black ash tree, which is used by weavers from Michigan to Maine. Many native plants used by basket weavers are endangered. Activists are working with their tribes to help save these plants and raise awareness.

Beadwork Today

Beadwork is a common Native American art form, but it uses beads brought from Europe and Asia. Glass beads have been used for almost 500 years in the Americas. Today, many beading styles are popular:

- In the Great Lakes, Ursuline nuns taught floral patterns to tribes. These patterns were quickly used in beadwork. Great Lakes tribes are known for their bandolier bags, which can take a whole year to finish.

- During the 20th century, Plateau tribes like the Nez Perce stitched lines of beads to create pictures.

- Plains tribes make dance outfits for men and women with many different beadwork styles.

- Subarctic tribes like the Dene bead fancy floral dog blankets.

- Eastern tribes like the Innu, Mi'kmaq, Penobscot, and Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) tribes are known for symmetrical scroll designs in white beads, called the "double curve." The Iroquois are also known for "embossed" beading. In this style, beads pop up from the surface when strings are pulled tightly.

- Indians of Jalisco and Nayarit, Mexico, have a unique way of using beads. They stick beads one by one to a surface, like wood or a gourd. They use a mix of resin and beeswax to do this.

Some modern Native beadworkers include Richard Aitson (Kiowa-Apache), Teri Greeves, Marcus Amerman (Choctaw), Roger Amerman, Martha Berry (Cherokee), Jamie Okuma (Luiseño-Shoshone-Bannock), Juanita Growing Thunder Fogarty, Rhonda Holy Bear, Charlene Holy Bear, and Elizabeth James Perry ([[Aquinnah Wampanoag-Eastern Band Cherokee).

Ceramics Today

In Caverna da Pedra Pintada in the Brazilian Amazon, pottery has been found that shows ceramics have been made in the Americas for 8,000 years. The Island of Marajó in Brazil is still a major center for ceramic art today. In Mexico, Mata Ortiz pottery continues the ancient Casas Grandes tradition of polychrome (made with 3 or more colors) pottery.

In the Southeast, the Catawba tribe is known for its tan-and-black pottery. In Oklahoma, Cherokees lost their pottery traditions until Anna Belle Sixkiller Mitchell brought them back. The Caddo tribe's pottery tradition had died out in the early 20th century. But Jereldine Redcorn made it popular again.

Pueblo people are especially known for their ceramic traditions. Some famous Pueblo ceramic artists include Nampeyo, Maria and Julian Martinez, Lucy Lewis, Virgil Ortiz, and Helen Cordero.

Northern potters in the Arctic are not as well-known as southern Arctic potters. However, ceramic arts are also popular in the Arctic. Inuit potter, Makituk Pingwartok of Cape Dorset uses a pottery wheel to create her award-winning ceramics.

Today, modern Native potters create many types of ceramics. These range from small pottery for use to giant ceramic sculptures. Some famous modern Native potters include Roxanne Swentzell of Santa Clara Pueblo, Nora Naranjo-Morse, Diego Romero of Cochiti Pueblo, and hundreds more artists.

Jewelry Today

-

German silver hair comb, by Bruce Caeser (Pawnee/Sac & Fox), Oklahoma, 1984.

-

Silver overlay bolo tie by Tommy Singer (Navajo), New Mexico, c. 1980s.

-

Navajo stamped silver belt buckle.

-

Shell gorget carved by Benny Pokemire (Eastern Band Cherokee).

Performance Art Today

Performance art is a new art form that started in the 1960s. It uses storytelling, music, and dance. Sometimes video, film, and textile design are also part of the performances. It lets artists talk directly to their audience. They can make people think about stereotypes and bring up current issues. For example, Rebecca Belmore, a Canadian Ojibway performance artist, highlights violence against First Nations women. She and James Luna, a Luiseño-Mexican performance artist, create complex outfits and props for their shows. They also play many characters.

On the other hand, Marcus Amerman, a Choctaw performance artist, plays one role: the Buffalo Man. He uses irony to comment on funny situations he finds himself in. Jeff Marley, Cherokee, uses humor from the "booger dance" tradition to make people think about current issues.

Erica Lord, Inupiaq-Athabaskan, uses her performance art to explore her mixed-race identity. A Bolivian group called Mujeres Creando, or "Women Creating," includes many Indigenous artists.

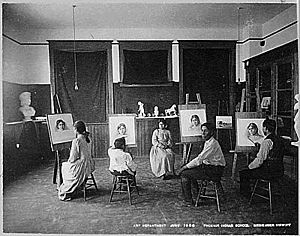

Photography Today

Native Americans started creating art with photography in the 19th century. Some even owned their own photography studios. These included Benjamin Haldane (1874–1941), Tsimshian of Metlakatla Village; Jennie Ross Cobb (Cherokee Nation, 1881–1959) of Park Hill, Oklahoma; and Richard Throssel (Cree, 1882–1933) of Montana. Their early photos are very different from the images by Edward Curtis.

Martín Chambi (Quechua, 1891–1973), a photographer from Peru, was one of the first Indigenous photographers in South America. Peter Pitseolak (Inuk, 1902–1973), from Cape Dorset, Nunavut, photographed Inuit life in the mid-20th century. He faced challenges from the harsh climate and extreme light. He developed his film in his igloo, and some photos were taken near oil lamps. Parker McKenzie (1897–1999), Nettie Odlety McKenzie (1897–1978), and Horace Poolaw (Kiowa, 1906–1984) took over 2000 photos of people in Western Oklahoma from the 1920s onward. Jean Fredericks (Hopi, 1906–1990) carefully changed Hopi views on photography. He did not sell his portraits of Hopi people to the public.

Today, countless Native people are professional art photographers. Native photographers use their skills in art videography, photo collage, digital photography, and digital art.

Printmaking Today

Not much is known about early American printmaking. However, 20th-century Native artists have used techniques from Japan and Europe. These include woodcut, linocut, serigraphy, monotyping, and other methods.

Printmaking has become very popular among Inuit communities. European-Canadian James Houston started a graphic art program in Cape Dorset, Nunavut, in 1957. Houston taught local Inuit stone carvers how to make prints from stone blocks and stencils. Print shops were also set up in nearby communities. These shops have tried etching, engraving, lithography, and silkscreen. Natural settings and animals are usually printed with little or no background. Shops made yearly catalogs so people could buy their prints.

Many Native painters turned their paintings into fine art prints. Some famous Native printers include Potawatomi artist Woody Crumbo. Also, Kiowa-Caddo-Choctaw painter T.C. Cannon, Mapuche printmaker Santos Chávez, Melanie Yazzie (Navajo), Linda Lomahaftewa (Hopi-Choctaw), Fritz Scholder (Cowlitz), Debora Iyall (Cowlitz), and Walla Walla artist James Lavadour.

Sculpture Today

Native Americans have created sculptures, both huge and small, for thousands of years. Stone sculptures are found everywhere in the Americas. They come in the forms of stelae, inuksuit, and statues. Alabaster stone carving is popular among Western tribes. Catlinite carving is traditional in the Northern Plains. Fetish-carving is traditional in the Southwest, especially among the Zuni. The Taíno of Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic are known for their zemis. These are sacred, three-pointed stone sculptures.

Inuit artists sculpt with walrus ivory, caribou antlers, bones, soapstone, serpentinite (a dark, greenish rock), and argillite (a rock made from clay). They often sculpt local animals and humans doing hunting or ceremonial activities.

Edmonia Lewis started using non-Native materials to sculpt. Others like Allan Houser (Warms Springs Chiricahua Apache), who used bronze, and Roxanne Swentzell (Santa Clara Pueblo), who used ceramic and bronze, followed.

The Northwest Coastal tribes are known for their woodcarving. Most famously, they carve giant totem poles that show clan crests (symbols of belonging to a tribe). Kwakwaka'wakw totem pole carvers like Charlie James, Mungo Martin, Ellen Neel, and Willie Seaweed kept the art alive. They also carved masks, furniture, bentwood boxes, and jewelry. Haida carvers include Charles Edenshaw, Bill Reid, and Robert Davidson. Besides wood, Haida also work with argillite. Glass sculpture became famous because of artists like Preston Singletary (Tlingit), Susan Point (Coast Salish), and Marvin Oliver (Quinault/Isleta Pueblo).

In the Southeast, woodcarving is more popular than sculpture. Willard Stone, of Cherokee descent, and Amanda Crowe (Eastern Band Cherokee) are two popular woodworking artists from the 20th century.

-

For Life in all Directions, Roxanne Swentzell (Santa Clara Pueblo), bronze.

-

Pai Tavytera traditional woodcarving, Paraguay, 2008.

Textiles Today

Fiber work from 10,000 years ago was found in Guitarrero Cave in Peru. Cotton and wool from alpaca, llamas, and vicuñas have been woven into detailed fabrics for thousands of years in the Andes. These are still important parts of Quechuas and Aymara culture today.

Kuna tribal members of Panama and Colombia are famous for their molas. These are cotton panels of fabric with complex designs. Two mola panels make a blouse. When a Kuna woman is tired of the blouse, she can take it apart and sell the molas to art collectors.

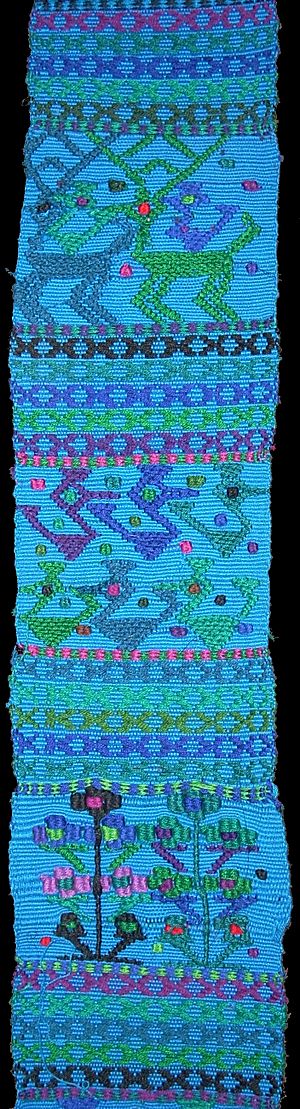

Mayan women have woven cotton with backstrap looms for centuries. They create items like huipils (traditional blouses). Detailed Maya textiles showed animals, plants, and figures from oral history. Many women join weaving groups (clubs that help women by providing looms and materials). This has helped Mayan women earn better money and spread Mayan textiles around the world.

After Seminole seamstresses started using sewing machines in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they invented a detailed patchwork tradition. They used patches of cloth and sewed them onto larger pieces in beautiful patterns. Seminole patchwork, for which the tribe is known today, became very popular in the 1920s.

Great Lakes and Prairie tribes are known for their ribbon work. This is found on clothing and blankets. Strips of silk ribbons are cut and sewn in layers, creating designs. The colors and designs might show the wearer's clan or gender. Powwow and other dance outfits from these tribes often feature ribbon work. These tribes are also known for their finger-woven sashes.

Pueblo men weave with cotton on upright looms. Their mantas (rectangular material worn as a blanket or dress) and sashes are usually made for ceremonies, not for outside collectors.

Navajo rugs are woven by Navajo women today. They use wool from Navajo-Churro sheep or commercial wool. Designs can be pictures or abstract shapes. They are based on traditional Navajo, Spanish, Oriental, or Persian designs. 20th-century Navajo weavers include Clara Sherman and Hosteen Klah. Klah helped start the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian.

In 1973, the Navajo Studies Department of the Diné College figured out how long it took a Navajo weaver to make a rug or blanket. From sheep shearing to selling, it took 345 hours. Out of these hours, the expert weaver needed: 45 hours to shear the sheep and prepare the wool, 24 hours to spin the wool, 60 hours to prepare and dye the wool, 215 hours to weave the piece, and only one hour to sell it.

Traditional textiles of Northwest Coast peoples are having a big comeback. Tlingit weaver Jennie Thlunaut (1982–1986) greatly helped this revival.

Modern textile artists include Lorena Lemunguier Quezada, a Mapuche weaver from Chile. Also, Martha Gradolf (Winnebago); Valencia, Joseph, and Ramona Sakiestewa (Hopi); and Melissa Cody (Navajo).

Cultural Sensitivity and Returning Art

Like in most cultures, Native peoples create some art that is only for sacred, private ceremonies. Many sacred objects are not allowed to be seen or touched by anyone without special permission or knowledge. Midewiwin birch bark scrolls are considered too culturally sensitive for public display. Medicine bundles, certain sacred pipes, and other tools of medicine people are also not displayed.

Navajo sandpainting is part of healing ceremonies. But sandpaintings can be made into permanent art that can be sold to non-Natives. This is okay as long as holy people are not shown. Many tribes do not allow their sacred ceremonies to be photographed or sketched.

Tribes and individuals do not always agree on what is okay to show the public. Many art pieces related to death or warriors' power are not displayed in museums. They have been returned to where they were made.

Museum Representation of Native American Art

Native American art has a long and complex history with museums since the early 1900s. In 1931, The Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts was the first big show of Native American art. After the Civil Rights Movement, art from minority groups was shown more in museums. However, Native American art was not always shown in a good way. For example, Native American art was sometimes placed next to dinosaur bones. This made it seem like they were a people of the past, not important today. Native American remains (bodies of the dead) were on display in museums until the 1960s.

Native American art has recently become more popular. There are more shows, places where it is seen, and displays in museums. For five months starting in October 2017, three Native American artworks were shown in the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 stops non-Indigenous artists from pretending to be Native American artists. Museum curators are careful to correctly show cultures that are not well-known. When they show these works in museums, it helps the public understand the artists and their cultures.