Taensa facts for kids

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| United States (Louisiana, Alabama) | |

| Languages | |

| Taensa, Mobilian trade jargon | |

| Religion | |

| Native tribal religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Natchez |

The Taensa were a Native American group. When Europeans first arrived in the late 1600s, the Taensa lived in what is now Tensas Parish, Louisiana. Their name has many spellings, like Taënsas, Tensas, and Tensaw. The meaning of their name is not known, but it is thought to be a name they used for themselves.

The Taensa people moved because of conflicts with the Chickasaw and Yazoo tribes. They first moved down the Mississippi River. In 1715, the French protected them, and they moved near the Tensas River in Mobile, Alabama. When the French gave their land east of the Mississippi River to the British in 1763, the Taensa returned to Louisiana. They settled near the Red River. By 1805, there were about 100 Taensa people. They later moved south to Bayou Boeuf and then to Grand Lake. After this, the remaining Taensa people are no longer found in historical records.

Contents

History of the Taensa People

Ancient Times

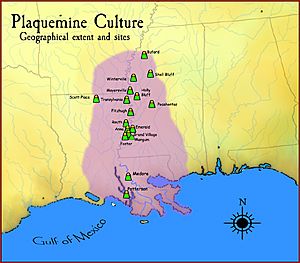

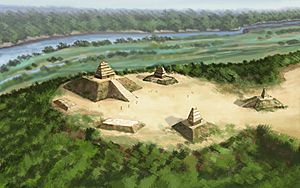

The Taensa and their close relatives, the Natchez, came from the ancient Plaquemine culture. This culture lived from about 1200 to 1700 CE. The Plaquemine culture was a type of Mississippian culture found mainly in the Lower Mississippi River valley.

These people had complex ways of life and religious beliefs. They lived in large villages with special mounds used for ceremonies. They were mostly farmers, growing maize (corn), pumpkins, squash, beans, and tobacco. Their history in the area goes back a long time, through the Coles Creek (700-1200 CE) and Troyville cultures (400-700 CE) to the Marksville culture (100 BCE to 400 CE).

The Tensas Basin region, where Taensa villages were found, has several ancient mound sites nearby. These include the Coles Creek era Balmoral Mounds and the Plaquemine era Routh Mounds and Flowery Mound sites.

Early Encounters

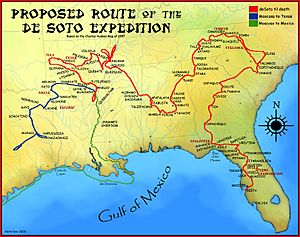

After the Hernando de Soto expedition in the 1540s, the Tensas Basin region saw more influences from the Mississippian culture. The Jordan Mounds site in northeastern Louisiana was built between 1540 and 1685. The people who built it were new to the area. They were likely refugees from the Mississippi River area, escaping problems caused by Europeans. By the late 1600s, this site was empty.

Some historians believe that the ancestors of the Taensa were among the people de Soto met in the 1540s. After de Soto's visit, many Native American groups faced big problems. European diseases caused many deaths, and their societies changed a lot. Because of this, some groups moved south toward their relatives.

Meeting Europeans

The first clear meeting between Europeans and the Taensa was in 1682. This was when the French La Salle expedition visited them. The Taensa had a village on Lake St. Joseph, a curved lake west of the Mississippi River. On March 22, 1682, a French priest with La Salle, Father Zenobius, spoke to the tribe there. La Salle's friend, Henri de Tonti, visited the Taensa again in 1686 and 1690. At that time, there were about 1,200 Taensa people living in seven or eight villages.

In 1698, French Catholic priests Antoine Davion and François de Montigny visited the Taensa. De Montigny started a mission among them for a short time. He wrote that there were 700 Taensa people then. In 1699, French explorer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville said the Taensa had 300 warriors and lived in seven villages. Most of these village names were from the Mobilian trade language, not the Taensa language.

During his time with the Taensa, de Montigny stopped some of their old customs that involved people during funeral ceremonies for a dead chief. Because of this, the Taensa blamed de Montigny when lightning struck their temple and burned it down. He left in 1790, and Jean-François Buisson de Saint-Cosme took over the mission. Like other Native Americans, the Taensa suffered from attacks by other tribes who captured people for trade and from European diseases like smallpox. As the Taensa population got smaller, de Saint-Cosme tried to get them to join the larger Natchez group, but it didn't work.

Later Years

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, French and British colonists in the American Southeast were competing for power. Traders from the British colony of Carolina had a large trading network with Native American groups. By 1700, this network reached the Mississippi River. The Chickasaw tribe, who lived north of the Taensa, often traded with Carolinian merchants for firearms. One profitable trade involved capturing Native Americans for trade. For many years, the Chickasaw, sometimes with the Natchez and Yazoo, attacked other tribes to capture people.

In 1706, the Taensa were afraid of an attack by the Chickasaw and Yazoo. They left their village on Lake St. Joseph and moved south to find safety with the Bayogoula tribe. Their village was about 25 miles (40 km) south of what is now Baton Rouge. Soon, conflicts started between the Taensa and Bayogoula. The Taensa attacked the Bayogoula, greatly reducing their numbers, and burned their village.

Even though their first meetings with Europeans were friendly, the competition between European powers caused problems for Native American groups. In 1715, the Taensa moved again, protected by the French. They went to lands near modern Mobile, on a branch of the Mobile River now called the Tensaw River. In 1763, the French lost the Seven Years' War and gave the eastern part of French Louisiana to the British. The Taensa, along with the Apalachee and Pakana, moved west of the Mississippi to French land on the Red River. There, they eventually joined with the Chitimacha people. By 1805, there were about 100 Taensa people left.

In the early 1800s, the Taensa asked the Spanish rulers for land in southeastern Texas. They were allowed to settle between the Trinity and Sabine rivers, but they never moved there. This was the last time the Taensa tribe appeared in historical records. They later moved south to Bayou Boeuf and then to Grand Lake, after which they disappeared from history.

Taensa Culture

The Taensa were a Natchezan people, meaning they were related to the Natchez tribe. They separated from the main Natchez group before Europeans arrived. Because of this, their languages, governments, religions, and daily lives were very similar to the Natchez. When they first appeared in history, they lived northwest of the Natchez, on the west side of the Mississippi River.

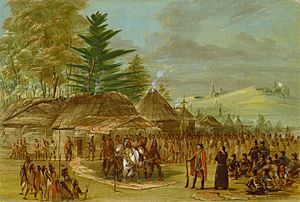

Like some other groups in the area, such as the Natchez, Tunica, and Houma, Taensa society was matrilineal. This means that family lines and important positions were passed down through the mother's side. Taensa society also had a clear hierarchy, with different classes of common people and leaders. This showed they were a simple chiefdom. Chiefs had great power and were treated with much respect. For example, when a chief visited the explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, helpers would sweep the road clean hours before the chief arrived.

Pottery and Art

Around 1550-1700 CE, Mississippian influences from Arkansas began to spread south into the Tensas Basin. This was most noticeable in how pottery was made. Mississippian people used different pottery shapes and materials than the Plaquemine people. By the late 1600s, these new pottery styles reached the Taensa. Taensa pottery used typical Mississippian shapes and crushed mussel shells to strengthen the clay. However, it still had engraved designs common to the Plaquemine area. This mix of styles makes the Taensa the last Mississippian culture group to live in the Tensas River valley of Louisiana.

Buildings and Villages

The Taensa were farmers who grew maize (corn) and lived in permanent villages. Their buildings were made of wattle and daub, which means they used woven sticks covered in clay. These buildings could be up to 30 feet (9 meters) long and 20 feet (6 meters) high. Their roofs were made of woven cane mats.

Their village on Lake St. Joseph was spread out, like the Natchez villages. It stretched for 3 miles (5 km) along the lake shore, with houses mixed with fields and forests. The main part of the village had a log palisade (a fence of strong posts). Inside this fence were the chief's house, the temple, and eight other buildings. Like other Native American groups in the Southeast, they also had an open plaza area. This plaza was used for public ceremonies like the Green Corn Ceremony and games like chunkey and the ballgame.

This village layout, with plazas next to mounds that had temples and important houses on top, was passed down from their ancestors. It was a common village design throughout the Southeast.

Chief's Home

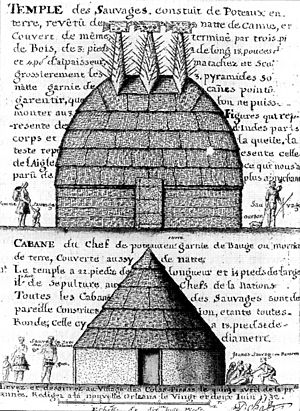

The temple and the chief's home were on opposite sides of the plaza. The chief's house was a square building, about 40 feet (12 meters) on each side. Its clay walls were 10 feet (3 meters) high and 2 feet (0.6 meters) thick. The roof was 15 feet (4.5 meters) high and covered with tightly woven cane mats that kept out water.

Great Temple

The Taensa temple was similar to the main temple of the Natchez. It stood on a low platform mound next to the plaza. Unlike the Natchez temple, it was surrounded by a palisade of sharp stakes decorated with human skulls from wars. Inside the palisade was a large dome-shaped building over 100 feet (30 meters) around. On top of the roof were three wooden eagle statues painted red, yellow, and white. These bird carvings faced east toward the rising sun. Woven cane mats covered the outside walls and roof, and the temple was painted red. A guard lived in a small shed near the door.

Inside the temple, there were shelves with beautifully woven and painted baskets. These baskets held the bones of chiefs and other honored dead. There were also stone, wood, and clay statues of humans and animals, stuffed owls, fish jawbones, snake parts, quartz crystals, and some European glass items. A special eternal fire, representing the Sun, was kept burning inside. Two priests and other helpers watched over this fire to make sure it never went out. Only the chief's close family could enter the temple. Food was often brought to the temple as offerings for their gods and the honored dead.

Beliefs and Religion

Taensa religious life centered on worshiping the sun. The sacred fire in their temple represented the sun. Their royal leaders were called "suns." Like the Natchez, they believed their chief, whose official name was Yak-stalchil (Great Sun), was related to the sun through his mother, the "Grande Soleille" (French for "female Great Sun"). Their stories said that long ago, a man and woman who shone like the sun came down to be their rulers. After that, they turned to stone. Early visitors wrote about stone statues in the temple that were worshiped as these original couple. The Taensa rulers claimed to be descendants of this mythical couple.

Similar stone temple statues have been found in northern Georgia, the Tennessee River Valley, and parts of Tennessee, Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois. While no stone statues have been found at Taensa sites, two were found at the Grand Village of the Natchez.

Taensa Language

Early writers said that the Taensa language was almost the same as the Natchez language. Missionaries learned these languages to try and convert the Taensa and Natchez to Christianity.

Linguists (people who study languages) believe the Natchezan language family is a language isolate. This means it's not clearly related to other language families. Some scholars think it might be related to the Muskogean languages, but this idea is generally not accepted by most linguists today.

The meaning of the Taensa name is unknown, but it's thought to be a name they used for themselves. The Chitimacha people, whom the Taensa eventually joined, called them Chō´sha.

Taensa Language Hoax

Between 1880 and 1882, a student in Paris named Jean Parisot published what he claimed was "material of the Taensa language." This included papers, songs, a grammar, and a list of words. It created a lot of interest among language experts. However, there were doubts about this material for many years. A famous American anthropologist and linguist, John R. Swanton, proved that the work was a hoax (a trick) in his writings from 1908-1910.

|

See also

In Spanish: Taensa para niños

In Spanish: Taensa para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |