Metallurgy in pre-Columbian America facts for kids

Metalworking in ancient America is all about how the Indigenous peoples of the Americas found, cleaned, and shaped metals before Europeans arrived in the late 1400s. People in these lands were using natural metals a very long time ago. Gold items found in the Andes mountains are from around 2155–1936 BCE. Copper items in North America date back to about 5000 BCE.

Early metalworkers found metals like gold and copper naturally. They didn't need to melt them from rocks (a process called smelting). Instead, they shaped the metal using hot and cold hammering. This changed the metal's shape but not its chemical makeup. In North America, there is no proof of melting or casting metals in ancient times. But in South America, it was very different. People there had full metalworking skills, including smelting and mixing different metals to create new ones (called alloying). Metalworking in Mesoamerica (like modern-day Mexico and Central America) might have started after people there met traders from Ecuador.

Contents

Metalworking in South America

Metalworking in South America likely began in the Andes region. This area includes modern-day Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, and Argentina. Early people hammered and shaped gold and natural copper into beautiful objects. Many of these were ornaments or decorations. The oldest gold items found are from 2155–1936 BCE. The earliest copper items are from 1432–1132 BCE. Some studies suggest copper smelting might have started in Bolivia as early as 2000 BCE.

In other parts of the world, metals became important for making weapons or tools. But in South America, metals were mostly valued for showing off wealth and status. Even during the Inca period, stone tools were still common. Metal objects were often fancy and found in important burials. This shows they were more for symbols than for everyday use.

Early Metalworking Skills

Around 1000–200 BCE, metalworking skills improved greatly. People started making amazing gold objects by joining small metal sheets. They also began using gold-silver alloy. Two main metalworking styles developed. One was in northern Peru and Ecuador. The other was in the Altiplano region (southern Peru, Bolivia, and Chile).

In the Altiplano, people started smelting copper from rocks around 1000 BCE. They found copper slag (waste from smelting) at several sites. The copper ore might have come from the border of Chile and Bolivia. Near Puma Punku in Bolivia, people used portable furnaces to make copper I-beams. These beams were used to connect large stone blocks in buildings. These copper pieces were made around 800–500 BCE.

Moche Culture and Smelting

Full smelting skills appeared with the Moche culture (200 BCE–600 CE) on the northern coast of Peru. Moche people dug up ores from shallow mines in the Andean foothills. They probably smelted the ores nearby. Pictures on metal objects and pottery show this process. Smelting happened in adobe brick furnaces. These furnaces had at least three blowpipes to push air in, making the fire hot enough.

The metal blocks (ingots) were then taken to workshops on the coast. These workshops were often near important towns, showing how special metal was. The objects made were still mostly decorations. Many were attached to beads. Some tools were made, but they were often highly decorated. They were usually found in important burials, suggesting they were symbolic.

People also started making gilded (gold-covered) or silvered objects. They created Tumbaga, which is an alloy of copper and gold, sometimes with silver. They also made arsenic bronze from copper sulfide ores. This was either a new invention or learned from the southern metalworking style. The earliest known use of powder metallurgy and working with platinum happened in Ecuador. Cultures like La Tolita (600 BCE - 200 CE) learned to solder platinum grains. They mixed platinum with copper, gold, and silver to make rings and ornaments.

Coastal groups in the Atacama Desert (like those near Tocopilla) made their own metal objects for daily use between 900 and 1400 CE.

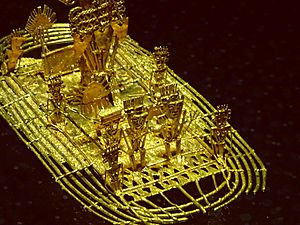

Metalworking slowly moved north into Colombia, Panama, and Costa Rica. It reached Guatemala and Belize by 800 CE. Around 100-700 CE, the Nahuange culture in Colombia developed "depletion gilding." This made ornamental variations like 'rose gold'. The Muisca people of modern-day Colombia made many small gold ornaments and religious items from about 600 CE. The gold Muisca raft is a very famous example. It is kept in the Gold Museum, Bogotá, which has a large collection of gold items from ancient cultures.

Inca Empire and Metal Use

Only with the Incas did metals become truly useful for practical things. Still, they were also used to show wealth and status. The Incas valued colors, linking gold to the sun and silver to the moon. Other metals also had value. Axe pieces, for example, were very important.

Some historians believe the Inca Empire expanded into Chile to get minerals. Others think the Incas invaded valleys in Argentina to get workers for Chilean mines. The Incas taught the Diaguita people their metalworking skills. Farther south, Mapuche tribes paid tribute to the Incas with gold. Archaeologists believe the Incas mined gold in Mapuche lands. The Mapuche people themselves valued gold culturally even before the Incas arrived. They used gold ornaments. Some Mapuche tools were made of copper and bronze.

Iron Use in Ancient America

Native Americans never learned to smelt iron. So, the Americas did not have an "Iron Age" before Europeans arrived. However, people did use natural iron ore. This came from minerals like magnetite, iron pyrite, and ilmenite. This happened mostly in the Andes and Mesoamerica from 900 BCE to about 500 CE. They mined, drilled, and polished these iron ores. This technology and the iron products were traded widely in Mesoamerica.

Lumps of iron pyrite and magnetite were mostly shaped into mirrors, pendants, and ornaments. These were for decoration and ceremonies. The Olmec (1500-400 BCE) and Chavin (900-300 BCE) cultures used curved iron ore mirrors for focusing light. Ilmenite 'beads' might have been small hammers for detailed work. The Olmec and Izapa (300 BCE – 100 CE) also seemed to use iron's magnetism to line up large stone monuments. They might have even made a simple compass using a magnetite bar.

Some uses of natural iron in Mesoamerica might have been for military purposes. It's thought that the Olmec sewed ilmenite 'beads' into protective armor or helmets. Iron pyrite mosaics and 'plates' were used on shields and breastplates for warriors. This was seen in the Teotihuacan (100 BCE – 600 CE), Toltec (800-1150 CE), and Chichen Itza (800-1200 CE) cultures.

Metalworking in Central America and the Caribbean

Gold, copper, and tumbaga objects began to be made in Panama and Costa Rica between 300–500 CE. People used open molds for casting and made delicate metal designs. By 700–800 CE, small metal sculptures were common. A wide range of gold and tumbaga ornaments were worn by high-status people in Panama and Costa Rica.

The oldest metal item from the Caribbean is a gold-alloy sheet from 70-374 CE. Most Caribbean metalwork is from 1200 to 1500 CE. These are usually small, simple pieces like sheets, pendants, beads, and bells. They are mostly gold or a gold alloy (with copper or silver). They were often hammered cold and polished. Some items seem to have been made using the lost-wax casting method. It is believed that some of these items were traded from Colombia.

Metalworking in Mesoamerica

Metalworking only appeared in Mesoamerica around 800 CE, with the best examples found in West Mexico. Like in South America, fine metals were seen as special for important people. The colors and sounds of metals were very appealing.

Ideas and goods from Ecuador and Colombia likely came by sea. This helped start early metalworking in Mesoamerica. Similar copper items like rings, needles, and tweezers are found in both West Mexico and Ecuador. Many bells were also found. These were made using the same lost-wax casting method as in Colombia. During this early period, copper was almost the only metal used.

Later, around 1200–1300 CE until the Spanish arrived, more influence came from further south. West Mexican metalworkers began to explore copper alloys. They needed different metal properties for specific items, especially axe-monies. This shows more contact with the Andes region. However, these new alloys were also developed to meet local needs. For example, bells with high tin content had a golden color, even if the tin didn't improve their strength.

The actual metal items and techniques came from the south. But West Mexican metalworkers used local ores, which were plentiful. The metal itself was not imported. Even when the technology spread to other parts of Mexico, items made from West Mexican ores were common. It's not always clear if the metal arrived as a raw ore, a metal block, or a finished item.

The Aztecs did not initially use metalworking much. They got metal objects from other groups. But as they conquered areas with metalworking, the technology spread. By the time the Spanish arrived, the Aztecs were starting to develop bronze smelting.

When the Tarascan State fought the Aztecs in the 1400s, the Tarascans successfully defended their empire. They used bronze weapons, which the Aztecs had not developed.

Metalworking in Northern America

Archaeologists have not found proof of metal smelting or alloying by ancient peoples north of the Rio Grande. However, they used natural copper a lot.

Old Copper Culture

Natural copper was very common, especially around the Great Lakes. The last ice age scraped away rocks, leaving copper pieces easy to find. People shaped copper by cold hammering very early on (8000–1000 BCE). There is also proof of copper mining, but the exact dates are debated.

Mining copper was very hard work. People might have used Hammerstones to break off pieces. They might also have built fires on top of copper deposits, then quickly poured water on the hot rock. This would create small cracks, making it easier to break off pieces.

The copper was then cold-hammered into shape. This could make it brittle. To prevent this, they would hammer and then heat the copper (a process called annealing). Finally, the object would be ground and sharpened using sandstone. Many copper bars have been found, suggesting they were traded.

Copper items from the Great Lakes have been found in the Eastern Woodlands. This shows that trade networks were widespread by 1000 BCE. Over time, less copper was used for tools and more for jewelry and ornaments. This might mean that societies were becoming more structured. Thousands of copper mining pits have been found along Lake Superior and on Isle Royale. These pits might be as old as 8,000 years. The copper was used to make spear points, tools, and mysterious crescent objects. Some archaeologists think these crescents were for religious ceremonies. Many have 28 or 29 notches, which is about the number of days in a lunar month.

The Old Copper Culture mostly thrived in Ontario and Minnesota. However, copper items have been found far away in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and even Alberta. These items were likely traded goods. Some evidence suggests that people from the Old Copper Culture did move northwest, bringing their metalworking skills with them.

This culture never became very advanced. They never discovered how to create alloys. Because of this, their copper tools could not compete with sharper flint tools. In later times, copper was almost only used for ceremonial items.

Copper in the Mississippian Culture

During the Mississippian period (800–1600 CE), important leaders in the central and southeastern United States used copper ornaments. These ornaments showed their high status. They made sacred copper into images linked to their Chiefly Warrior cult. These include Mississippian copper plates found in many states. Some famous plates show birds of prey and dancing warriors. These plates helped archaeologists understand the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex.

The only Mississippian site where a copper workshop has been found is Cahokia in Illinois. Archaeologists found many copper pieces there. Studies show that Mississippian copper workers hammered copper into thin sheets. They did this by repeatedly hammering and heating the copper (annealing) over wood fires.

After the Mississippian way of life changed around the 1500s due to European arrival, copper remained special. Many Eastern tribes thought copper was sacred. Copper nuggets are still included in medicine bundles among Great Lakes tribes. In the 1800s, some Muscogee Creeks carried copper plates that they considered very sacred.

Iron in the Pacific Northwest

Native ironwork in the Northwest Coast has been found at places like the Ozette Indian Village Archeological Site. Iron chisels and knives were discovered there. These tools were made around 1613. They were crafted from iron that came from Asian shipwrecks. These shipwrecks were carried by the Kuroshio Current to the coast of North America.

Working with Asian drift iron was common in the Northwest before Europeans arrived. Several native peoples, including the Chinookan peoples and the Tlingit, had their own words for this metal. Shipwrecks from Japan and China were common in the North Pacific. The iron tools and weapons from these ships provided materials for local ironwork. Other sources of iron, like meteorites, were also sometimes used.

Inuit Metal Use

Local Inuit people got iron from the large Cape York meteorite. Pieces of this meteorite landed off Greenland and in the surrounding area a long time ago.

See also

In Spanish: Metalurgia precolombina en América para niños

In Spanish: Metalurgia precolombina en América para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |