Huns facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Huns

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 370s–469 | |||||||||||||||||||||

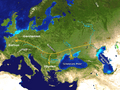

Territory under Hunnic control, c. 450 AD

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Attila's Court | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Tribal Confederation | ||||||||||||||||||||

| King or chief | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 370s?

|

Balamber? | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• c. 395 – ?

|

Kursich and Basich | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• c. 400–409

|

Uldin | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Huns appear north-west of the Caspian Sea

|

pre 370s | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 370s | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Attila and Bleda become co-rulers of the united tribes

|

437 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Death of Bleda, Attila becomes sole ruler

|

445 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 451 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Invasion of northern Italy

|

452 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 454 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Dengizich, son of Attila, dies

|

469 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

The Huns were a group of nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th centuries AD. They were known for their powerful armies and swift attacks.

The Huns often raided the Eastern Roman Empire. In 451, they invaded the Western Roman province of Gaul. There, they fought a combined army of Romans and Visigoths at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields. In 452, they invaded Italy. After their famous leader Attila died in 453, the Huns became less of a threat to Rome. They lost much of their empire after the Battle of Nedao around 454 AD.

We don't know much about the Hunnic culture. They had their own language, but only a few words and names from it are known today. The Huns ruled over many different peoples who spoke various languages. These groups sometimes kept their own leaders. The Huns' main fighting style was mounted archery, meaning they were skilled archers on horseback.

Contents

The Huns: Origins and Appearance

Where Did the Huns Come From?

Historians are still not completely sure about the exact origins of the Huns. Most experts agree that they came from Central Asia. Ancient writings say that the Huns suddenly appeared in Europe around 370 AD.

How Did the Huns Look?

Ancient descriptions of the Huns often focused on their unusual appearance, especially from a Roman point of view. They were often described as short, with tanned skin and round, shapeless heads. Many writers mentioned that the Huns had small eyes and flat noses.

History of the Huns

Early Hunnic History

The early history of the Huns in the 4th century is not very clear. The Huns did not leave behind their own written records. The Romans first learned about the Huns when the Huns invaded the Pontic steppes. This invasion forced thousands of Goths to flee into the Roman Empire in 376 AD.

The Huns conquered the Alans and then most of the Eastern and Western Goths. Many Goths fled into the Roman Empire. In 395 AD, the Huns launched their first major attack on the Eastern Roman Empire. They attacked areas like Thrace, Armenia, and Cappadocia. They even reached parts of Syria and threatened the city of Antioch. At the same time, the Huns also invaded the Sasanian Empire (Persia). This invasion was successful at first, but the Huns were later defeated by a Persian counterattack.

During a break from attacking the Eastern Roman Empire, the Huns may have threatened tribes further west. A Hun leader named Uldin is the first Hun mentioned by name in Roman records. He led a group of Huns and Alans who helped defend Italy against other invaders. Uldin also defeated Gothic rebels around 400-401 AD. In 408 AD, Uldin's Huns again put pressure on the Eastern Romans by crossing the Danube River and raiding Thrace. The Romans tried to pay Uldin to leave, but his price was too high. Instead, they paid his commanders, causing many Huns to leave Uldin's group. Uldin escaped back across the Danube and is not mentioned again.

Hunnic fighters were sometimes hired as mercenaries by both the Eastern and Western Roman Empires, as well as by the Goths, in the late 4th and 5th centuries. In 433 AD, some parts of Pannonia (a Roman province) were given to the Huns by Flavius Aetius, a powerful Roman general.

Attila: The Famous Hun Leader

From 434 AD, the brothers Attila and Bleda ruled the Huns together. They were very ambitious, just like their uncle Rugila. In 435 AD, they forced the Eastern Roman Empire to sign the Treaty of Margus. This treaty gave the Huns trade rights and a yearly payment from the Romans.

When the Romans broke the treaty in 440 AD, Attila and Bleda attacked a Roman fortress on the Danube River. This started a war between the Huns and Romans. The Huns defeated a weak Roman army and destroyed several cities. Even though a truce was made in 441 AD, the Romans failed to pay the tribute again in 443 AD. This led to more war. Hun armies got close to Constantinople (the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire) and sacked several cities. They defeated the Romans at the Battle of Chersonesus. The Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II had to agree to the Huns' demands and signed a peace treaty in 443 AD.

Bleda died in 445 AD, and Attila became the only ruler of the Huns. In 447 AD, Attila invaded the Balkans and Thrace. The war ended in 449 AD with an agreement where the Eastern Romans agreed to pay Attila a huge yearly payment of 2100 pounds of gold.

While raiding the Eastern Roman Empire, the Huns had good relations with the Western Roman Empire. However, Honoria, the sister of the Western Roman Emperor Valentinian III, sent Attila a ring and asked for his help to avoid an arranged marriage. Attila claimed her as his bride and demanded half of the Western Roman Empire as a dowry. Also, a dispute arose about who should be the next king of the Salian Franks.

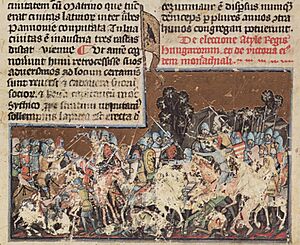

In 451 AD, Attila's forces entered Gaul (modern-day France). They first attacked Metz, then moved west to besiege Orléans. Emperor Valentinian III sent his general, Flavius Aetius, to help Orléans. A combined army of Roman and Visigoths then fought the Huns at the famous Battle of the Catalaunian Plains.

The next year, Attila again demanded Honoria and territory in the Western Roman Empire. He led his army across the Alps into Northern Italy, where he sacked and destroyed many cities. To prevent Rome from being sacked, Emperor Valentinian III sent three envoys, including Pope Leo I, to meet Attila. They met near Mantua and convinced Attila to withdraw from Italy and negotiate peace.

The new Eastern Roman Emperor Marcian then stopped paying tribute to Attila. This made Attila plan to attack Constantinople. However, in 453 AD, Attila died from a hemorrhage on his wedding night.

After Attila's Reign

After Attila's death in 453 AD, the Hunnic Empire faced big problems. The different Germanic peoples they had conquered started to fight for their freedom. Ellac, Attila's favorite son, led the Huns against the Gepid king Ardaric at the Battle of Nedao. Ardaric led a group of Germanic tribes who wanted to overthrow Hunnic rule. The Goths also rebelled the same year.

These events did not completely destroy Hunnic power, but the Huns lost many of their Germanic subjects. At the same time, new groups of Oghur Turkic-speaking peoples arrived from the East, like the Saragurs and Onogurs. In 463 AD, the Saragurs defeated a group of Huns and took control of the Pontic region.

The western Huns, led by Dengizich, faced difficulties. In 461 AD, they were defeated by the Goths. Dengizich's brother, Ernak, who ruled another group of Huns, wanted to focus on the new Oghur peoples. Dengizich attacked the Romans in 467 AD without Ernak's help. He was surrounded and agreed to surrender if his people were given land and food. During talks, a Hun working for the Romans convinced the Goths to attack their Hun overlords. The Romans then attacked the fighting Goths and Huns, defeating them. In 469 AD, Dengizich was defeated and killed in Thrace.

After Dengizich's death, the Huns seem to have mixed with other groups like the Bulgars. Some historians believe that the Huns continued under Ernak, becoming the Kutrigur and Utigur Hunno-Bulgars. This idea is still debated by experts.

Hunnic Lifestyle and Economy

Life as Nomads

The Huns are usually described as pastoral nomads. This means they lived by herding animals and constantly moved from one pasture to another to feed their livestock. Ancient sources say that the Huns did not practice farming.

Horses and Travel

As nomads, the Huns spent a lot of time riding horses. They rode so much that some sources say they walked clumsily when on foot. Roman writers described Hunnic horses as not very pretty. We don't know the exact breed of horse they used, but some think it might have been a type of Mongolian pony. Interestingly, no horse remains have been found in Hunnic burials.

Besides horses, ancient writings say the Huns used wagons for travel. These wagons mainly carried their tents, stolen goods, and their elderly, women, and children.

How Huns Traded with Romans

The Huns received a lot of gold from the Romans. This gold was either payment for fighting as mercenaries or as tribute (payments to avoid attacks). Raiding and looting also provided the Huns with gold and other valuable items.

People captured by the Huns, both civilians and soldiers, could be ransomed back (bought back for money). If not, they might be sold as slaves to Roman slave dealers. The Huns themselves didn't have much use for slaves because of their nomadic lifestyle.

The Huns also traded with the Romans. They exchanged horses, furs, meat, and slaves for Roman weapons, linen, grain, and other luxury goods.

Hunnic Empire and Rule

Ruling the Empire

Except for Attila's time as sole ruler, the Huns often had two leaders. Attila himself later made his son Ellac a co-king.

In the 390s, most Huns were probably based around the Volga and Don rivers in the Pontic Steppe. But by the 420s, the Huns moved to the Great Hungarian Plain. This was the only large grassland near the Roman Empire that could support many horses. However, some historians believe they still controlled the Pontic Steppe north of the Black Sea.

The Huns conquered the Hungarian Plain in stages. It's not clear exactly when they took control of the north bank of the Danube River. Some think it might have been as early as the 370s. The dates when they gained control of Roman territory south of the Middle Danube, like Pannonia, are also debated. It was likely between 406-407 AD and 431-433 AD. Other than these areas, the Huns did not try to conquer or settle on Roman land. After Attila's death, the Huns were driven out of Pannonia. Some seem to have returned to the Pontic Steppe, while one group settled in Dobruja.

The Huns ruled over many other groups, including Goths, Gepids, Sarmatians, Heruli, Alans, and others. Some historians suggest that the Huns moved some of these groups along the Danube River. The conquered peoples of the Huns were led by their own kings. People recognized as ethnic Huns seemed to have more rights and higher status.

How the Huns Fought Wars

One of the main sources of information about Hunnic warfare comes from the Roman writer Ammianus Marcellinus. He described how the Huns fought:

They sometimes fight when provoked, and then they enter the battle drawn up in wedge-shaped masses, while their medley of voices makes a savage noise. And as they are lightly equipped for swift motion, and unexpected in action, they purposely divide suddenly into scattered bands and attack, rushing about in disorder here and there, dealing terrific slaughter; and because of their extraordinary rapidity of movement they are never seen to attack a rampart or pillage an enemy's camp. And on this account you would not hesitate to call them the most terrible of all warriors, because they fight from a distance with missiles having sharp bone, instead of their usual points, joined to the shafts with wonderful skill; then they gallop over the intervening spaces and fight hand to hand with swords, regardless of their own lives; and while the enemy are guarding against wounds from the sabre-thrusts, they throw strips of cloth plaited into nooses over their opponents and so entangle them that they fetter their limbs and take from them the power of riding or walking.

Based on this description, historians believe that the Huns' fighting methods were similar to those used by other nomadic horse archers.

Hunnic armies relied on being very mobile and knowing when to attack and when to retreat. An important tactic they used was a "feigned retreat." This meant pretending to run away, then suddenly turning back to attack the disorganized enemy. Accounts of battles show that the Huns protected their camps using portable fences or by arranging their wagons in a circle.

The Huns' nomadic lifestyle helped them become excellent horsemen. They also trained for war by hunting often. Some scholars suggest that after settling on the Hungarian Plain, the Huns found it harder to maintain their horse cavalry and nomadic way of life. This might have made them less effective fighters over time.

The Huns almost always fought alongside non-Hunnic groups, such as Germanic or Iranian peoples, or their allies. As one historian notes, the Huns' military strength grew quickly by adding more and more Germanic peoples from central and eastern Europe. At the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, Attila placed his conquered peoples on the sides of his army, while the Huns held the center.

Historian Peter Heather points out that the Huns were able to successfully attack walled cities and fortresses in their campaign of 441 AD. This means they could build siege engines. Heather suggests they might have learned this from serving with the Roman general Flavius Aetius, from captured Roman engineers, or from needing to attack wealthy cities along the Silk Road.

Hunnic Society and Culture

Languages Spoken by the Huns

Many different languages were spoken within the Hun Empire. The Roman historian Priscus noted that the Hunnic language was different from other languages spoken at Attila's court. Some scholars believe that Gothic was used as a common language (lingua franca) in the Hunnic Empire. One historian, Hyun Jin Kim, suggests that the Huns might have used as many as four languages in their government: Hunnic, Gothic, Latin, and Sarmatian.

As for the Hunnic language itself, there's no agreement on how it relates to other languages. Only three words are recorded in ancient sources as being "Hunnic," and they seem to come from an Indo-European language.

Hunnic Religion

Very little is known about the religion of the Huns. The Roman writer Ammianus Marcellinus claimed that the Huns had no religion. The Christian writer Salvian in the 5th century called them Pagans.

Historian John Man suggests that the Huns during Attila's time likely worshipped the sky and the steppe god Tengri. There is also some evidence that the European Huns practiced human sacrifice. Besides these Pagan beliefs, there are many records of Huns converting to Christianity and receiving Christian missionaries.

Burials and Customs

We have an account of Attila's funeral from the historian Jordanes, possibly based on Priscus's writings. Jordanes reports that the Huns cut their hair and cut their faces with swords as part of the ceremony. This was a common custom among steppe peoples. After this, Attila's coffin was placed in a silk tent. Horsemen rode around it, singing funeral songs called a strava. The coffin was then covered in precious metals and buried secretly with weapons. The slaves who dug the grave were killed to keep the burial location a secret.

Since 1945, many archaeological finds have been made. However, as of 2005, only about 200 burials have been identified as possibly Hunnic. These include burials in the Carpathian Basin and the Pontic Steppe. Hun-period burials often contain many valuable items, which archaeologists call "offerings to the dead." However, the richest nomadic burials have been found outside the Carpathian Basin, even though this was Attila's main power center. Most burials from the Carpathian Basin match the culture of the local Germanic peoples. The lack of Hunnic burials might mean that most Hunnic funerals did not leave remains, or that they adopted Germanic customs.

Often, nomadic graves from the Hun period show signs of objects being burned, likely as part of the burial ceremonies. The common nomadic practice of burying animal parts, like shoulder blades, with the deceased is rare in the Carpathian Basin. Also, while Central Asian and East European nomadic burials often feature large mounds called kurgans, these are completely missing in the Carpathian Basin.

Hunnic Material Culture

We learn about the Huns' material culture from ancient descriptions and from archaeological discoveries.

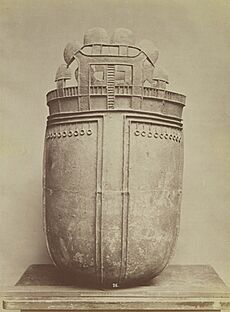

Cauldrons

Archaeologists have found many cauldrons that are believed to have been made by the Huns. Although often called "bronze cauldrons," they are usually made of copper, which is often of poor quality. One historian lists 19 known Hunnic cauldrons found across Central and Eastern Europe and Western Siberia. He suggests that the Huns were not very skilled metalworkers and that the cauldrons were likely made where they were found. They come in different shapes and are sometimes found with other types of vessels. These cauldrons were probably used for cooking meat. However, many are found near water and not buried with people, which might mean they also had a religious use. These cauldrons seem to be similar to those used by the Xiongnu people.

Clothing

Ancient Greek and Roman sources don't give many good descriptions of Hunnic clothing. However, we know from Central Asian burials that they probably wore a type of long coat called a khalat. The East Roman historian Priscus once saw a Greek merchant wearing "Scythian" clothing and thought he was a Hun. This suggests that the Huns had a distinct style of dress.

Ammianus reports that the Huns wore clothes made of linen or mouse furs and goatskin leggings, which they did not wash. While furs and linen might be accurate, the idea of them wearing dirty animal skins and mouse furs likely comes from negative stereotypes about "primitive barbarians." Priscus also mentions expensive and rare animal furs. He also noted that Attila's queen, Kreka, had handmaidens who wove decorative linen.

Based on finds from modern Kazakhstan, archaeologist Joachim Werner suggests that Hunnic clothing likely included knee-length, sleeved smocks (the khalat), sometimes made of silk, along with trousers and leather boots. Saint Jerome and Ammianus both describe the Huns wearing a round cap, probably made of felt. Because nomadic clothing didn't need brooches, the absence of this common item in some barbarian burials might show Hunnic cultural influence. According to one historian, the Huns' shoes were probably made of sheep's leather. A figurine from Bántapuszta shows a warrior wearing high, bulky boots connected to his chainmail by straps, a style also mentioned by Priscus.

Artistic Decoration

Jewelry and weapons linked to the Huns are often decorated in a colorful, cloisonné style. This style uses thin metal strips to create compartments for gems or enamel.

Archaeologist Joachim Werner believed that the Huns developed a unique "Danubian" art style. This style combined Asian gold-working techniques with the huge amounts of gold the Romans paid as tribute to the Huns. This style then influenced European art. However, more recent discoveries show that this colorful style existed before the Huns arrived in Europe. Also, historian Warwick Ball argues that the decorated items from the Hunnic period were probably made by local craftspeople for the Huns, rather than by the Huns themselves.

A copper-plated Hun-period figurine found in Hungary shows a man in armor with decorated pants and collars. Archaeological finds suggest that the Huns wore gold plaques as ornaments on their clothing, as well as imported glass beads. These gold plaques were likely used to decorate the edges of festive clothing for both men and women. This fashion seems to have been adopted by both the Huns and East Germanic leaders. Both men and women have been found wearing shoe buckles made of gold and jewels in Eastern Europe, but of iron or bronze in Central Asia. The golden shoe buckles are also found in non-Hunnic graves in Europe.

Both ancient writings and archaeological finds from graves confirm that Hunnic women wore beautifully decorated golden or gold-plated diadems (headbands). These diadems, along with parts of bonnets, were likely symbols of leadership. Women are also found buried with small mirrors, originally from China, which often seem to have been intentionally broken when placed in the grave. Hunnic women appear to have worn necklaces and bracelets made mostly of imported beads from various materials. Men are often found buried with one or two earrings and, unusually for nomadic people, bronze or golden neck rings.

Tents and Homes

Ammianus reports that the Huns had no buildings. However, he mentions that the Huns had tents and also lived in wagons. No tents or wagons have been found in Hunnic archaeological sites because they were not buried with the dead. One historian believes that the Huns likely had "tents of felt and sheepskin." Priscus once mentions Attila's tent, and Jordanes reports that Attila lay in state in a silk tent. However, by the mid-5th century, Priscus mentions that the Huns owned permanent wooden houses. Historians believe these houses were built by their Gothic subjects.

Bows and Arrows

Ancient Roman sources emphasize how important the bow was to the Huns. It was their main weapon. The Huns used a composite or reflex bow, often called the "Hun-type." This style had spread to all steppe nomads in Eurasia by the time the Huns appeared. These bows measured between 120 and 150 centimeters (about 4 to 5 feet). Examples are very rare in archaeological finds, with most found in the Pontic Steppe and Middle Danube region of Europe. Because so few examples survive, it's hard to say exactly how powerful these bows were.

The bows were difficult to make and were probably very valuable. They were made from flexible wood, strips of antler or bone, and animal sinew. The bone made the bow more durable but possibly less powerful. The graves of people identified as "princes" among the Huns have been found with golden, ceremonial bows across a wide area from the Rhine to the Dnieper rivers. Bows were buried with the object placed across the chest of the deceased.

These bows shot larger arrows than earlier types. The appearance of iron, three-lobed arrowheads in archaeological records is seen as a sign of their spread. Ammianus, while noting the importance of Hunnic bows, didn't seem to know much about them. He incorrectly claimed that the Huns only used bone-pointed arrows.

Riding Gear

Riding equipment and harnesses are often found in Hun-period burials. The Huns did not use spurs. Instead, they used whips to guide their horses. Handles of such whips have been found in nomadic graves. The Huns are often thought to have invented the wooden-framed saddle. However, more recent research suggests that the Huns still used an older style of saddle made of padding.

The Huns are also commonly credited with bringing the stirrup to Europe. Stirrups seem to have been used by other groups in Asia from the 5th century AD onwards. However, no stirrups have been found in Hunnic burials, and there's no written evidence that they used them. Without stirrups, the Huns would not have had the stability to fight in close combat on horseback. This suggests they preferred fighting with bows and arrows. The lack of stirrups would have required special techniques for firing arrows from horseback.

Armor

Defensive equipment and chainmail are rarely found in Hunnic period graves. Ammianus does not mention the Huns using any armor. However, it is believed that the Huns used lamellar armor, a type of armor popular among steppe nomads at that time. Metal armor was probably rare. The Huns may have used a type of helmet called the Spangenhelm, but Hunnic nobles might have worn various types of helmets.

Swords and Other Weapons

Ammianus reports that the Huns used iron swords. Ceremonial swords, daggers, and decorated scabbards are often found in Hun-period burials. Additionally, pearls are frequently found with swords. These decorations may have had a religious meaning. Many scholars believe that the Huns started the fashion of decorating swords with cloisonné. However, some argue that these swords show strong Mediterranean influence and may have been made by Byzantine workshops.

Some historians doubt that the Huns could make iron themselves. But others argue that it's "absurd" to think the Huns fought their way across Europe with only traded or captured swords. One unique sword used by the Huns and their subject peoples was the narrow-bladed long seax. Many scholars believe the Huns introduced this type of sword to Europe. In its earliest forms, these swords seem to have been shorter, stabbing weapons.

The Huns, along with the Alans and Eastern Germanic peoples, also used a type of sword called an East Germanic or Asian spatha. This was a long, double-edged iron sword with an iron cross-guard. These swords would have been used to cut down enemies who were already fleeing from the Huns' arrows. Roman sources also mention lassos as weapons used at close range to trap opponents.

Some Huns or their subject peoples may also have carried heavy lances, as mentioned for some Hunnic mercenaries in Roman sources.

See also

In Spanish: Hunos para niños

In Spanish: Hunos para niños

- Amal dynasty

- Huna people

- List of Huns

- List of rulers of the Huns

- Nomadic empire

Images for kids